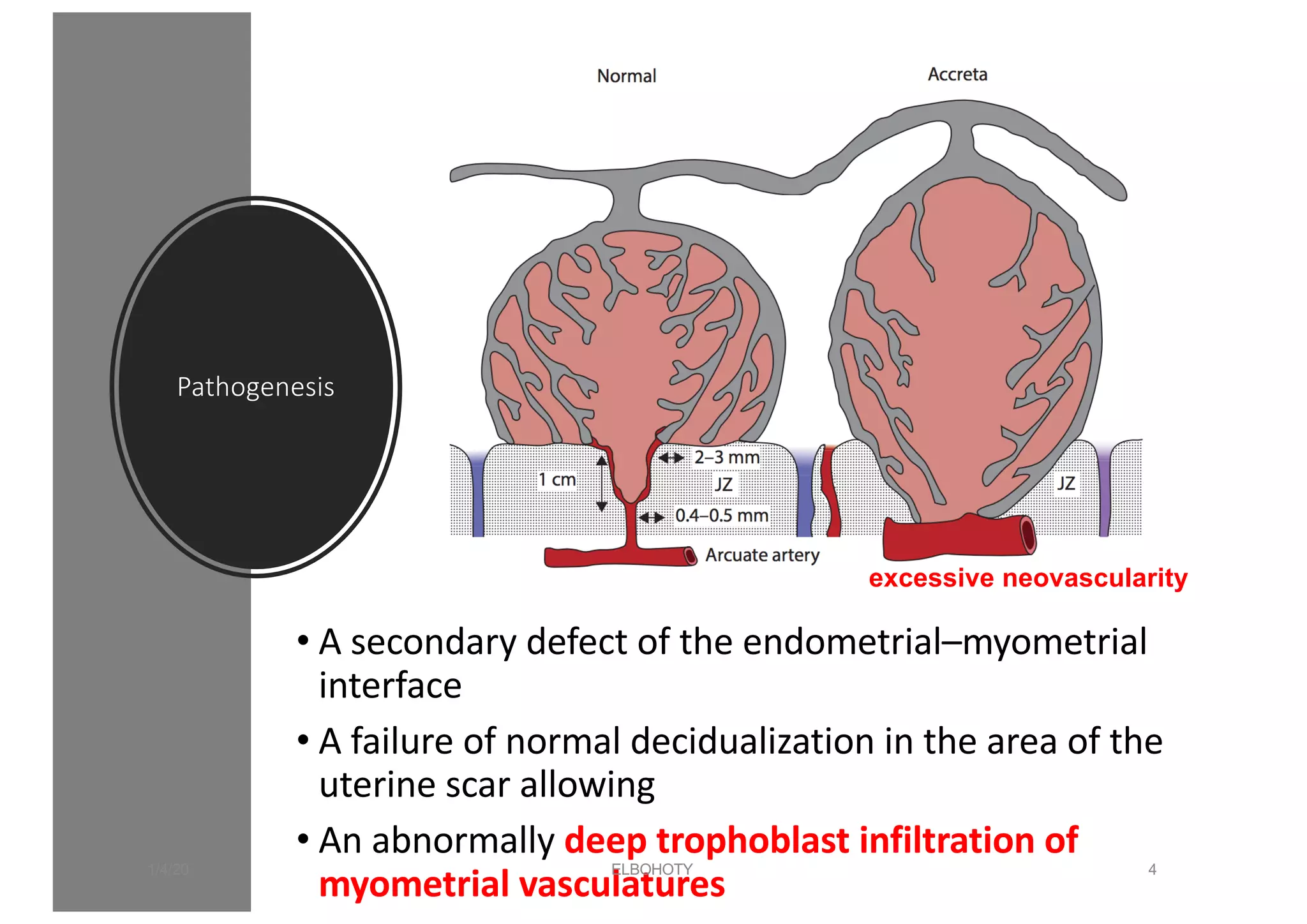

This document discusses placenta accreta spectrum disorders, including challenges in management. Key points include: PAS disorders occur when the placenta invades the uterine wall abnormally. Risk factors include prior c-sections and placenta previa. Incidence has risen with increasing c-section rates. Ultrasound is used to diagnose but risks false positives/negatives. Management involves a multidisciplinary team and individualized delivery timing/plan. Surgery poses challenges like hemorrhage, but techniques like leaving the placenta in situ and internal iliac ligation can help. Careful dissection is needed to avoid injury to structures like the bladder and ureters.