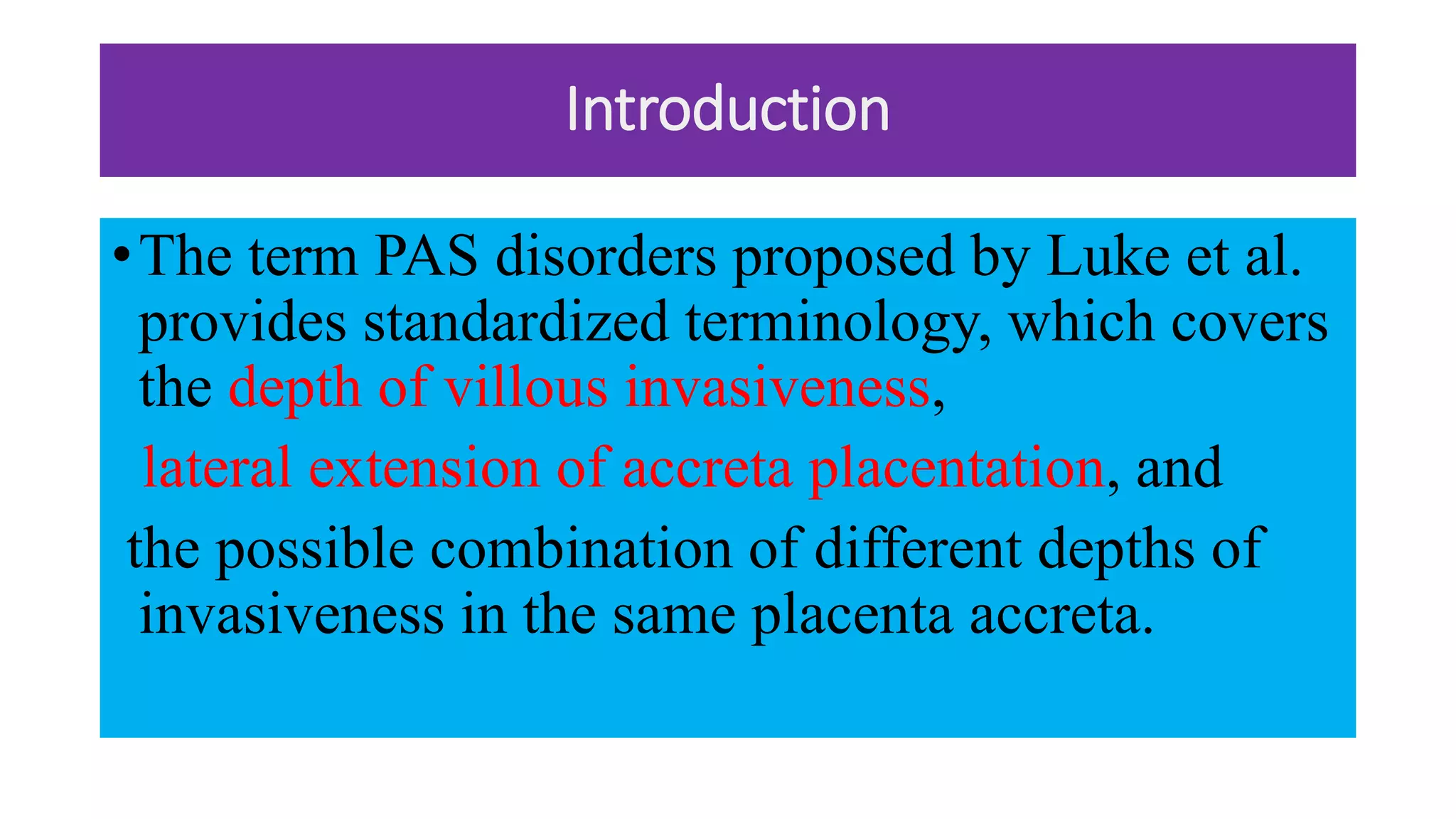

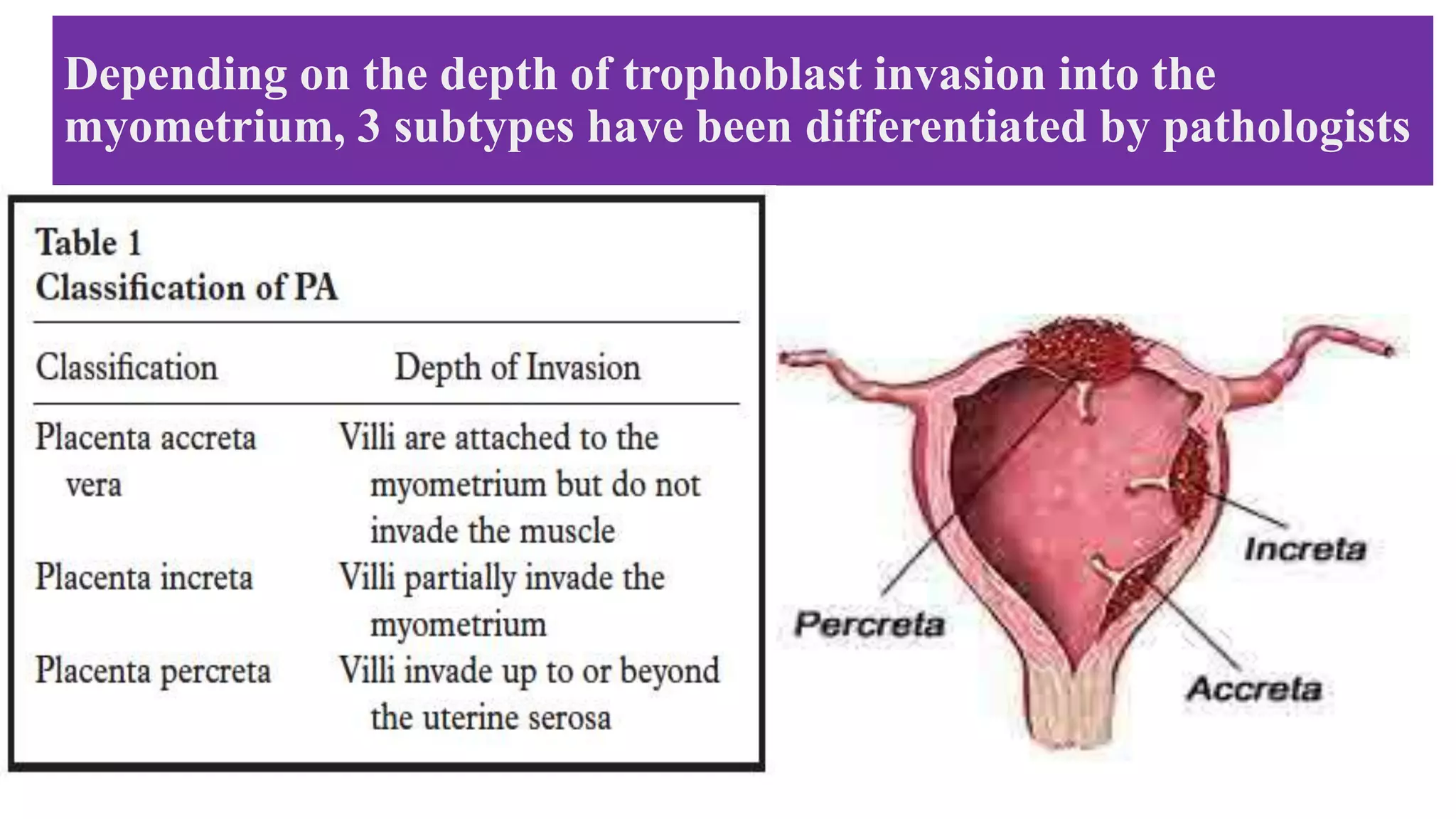

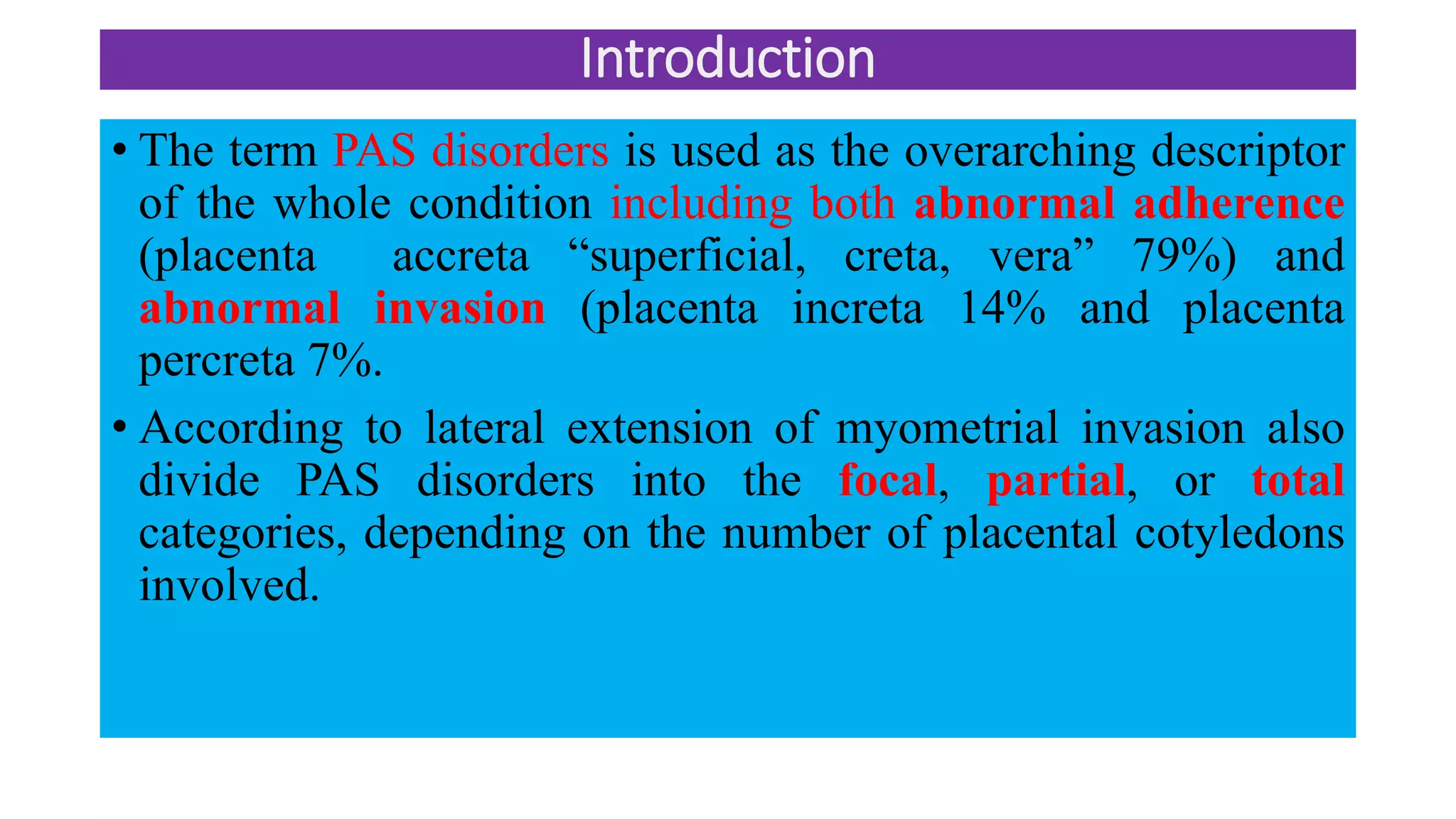

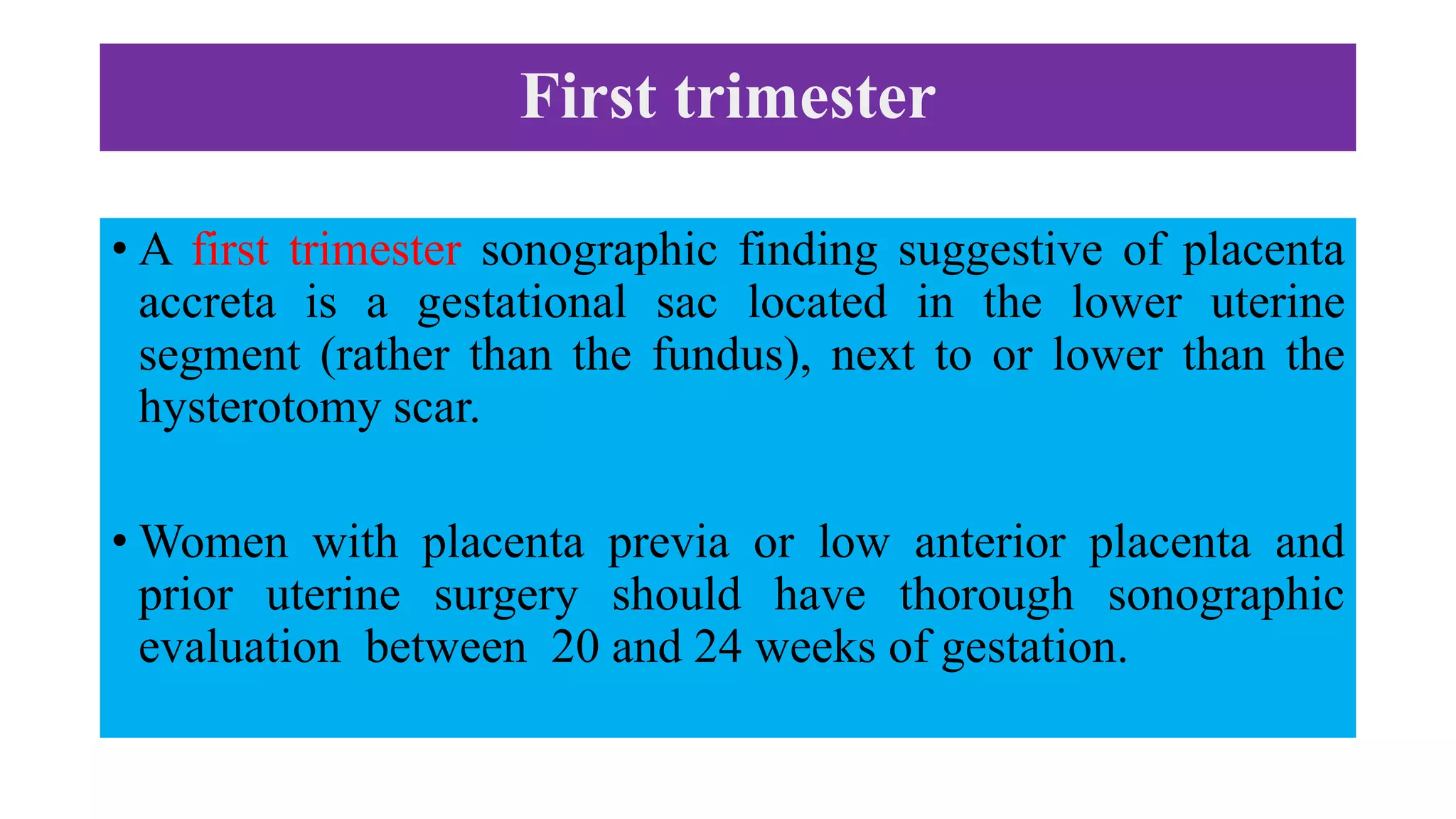

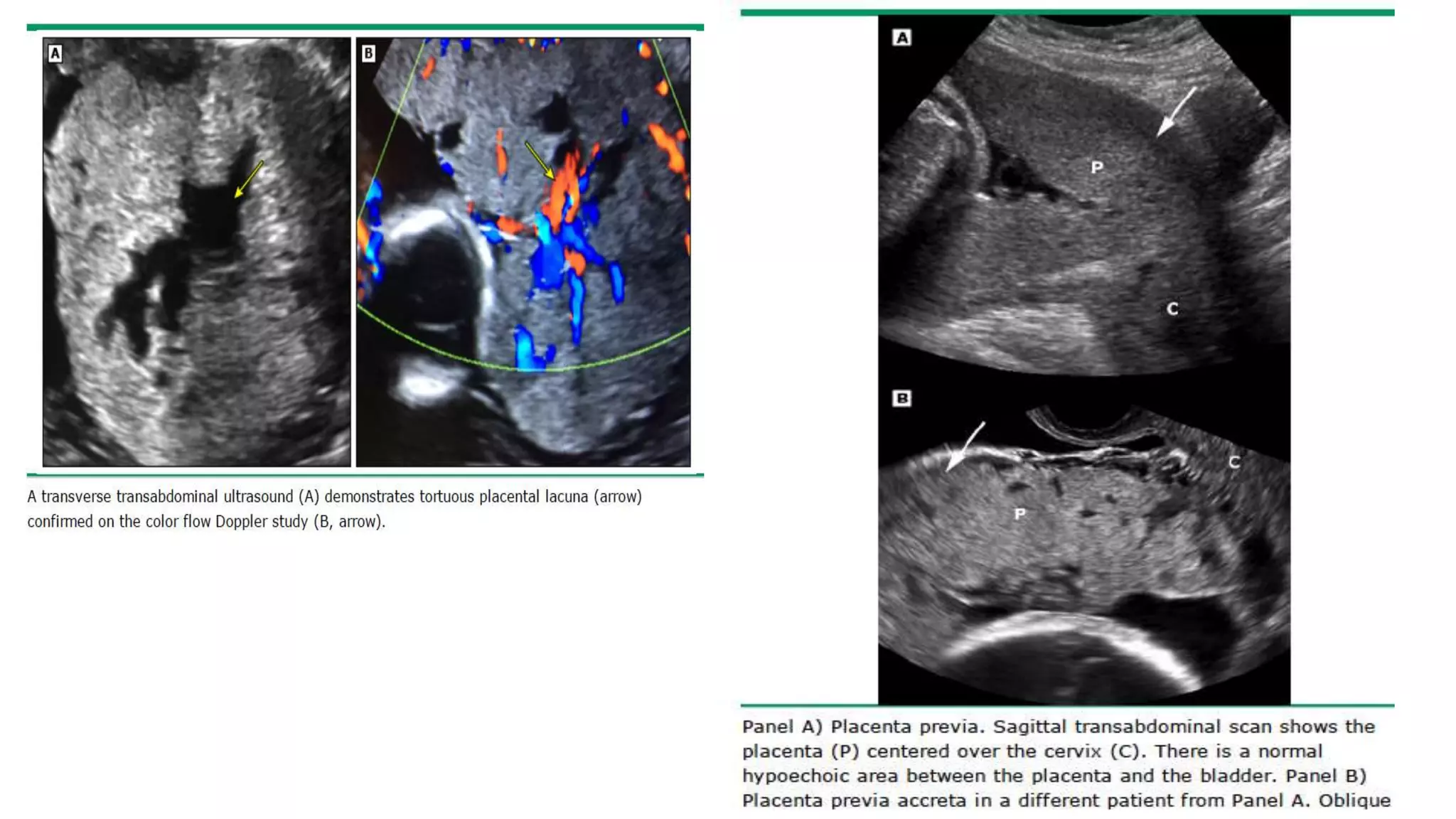

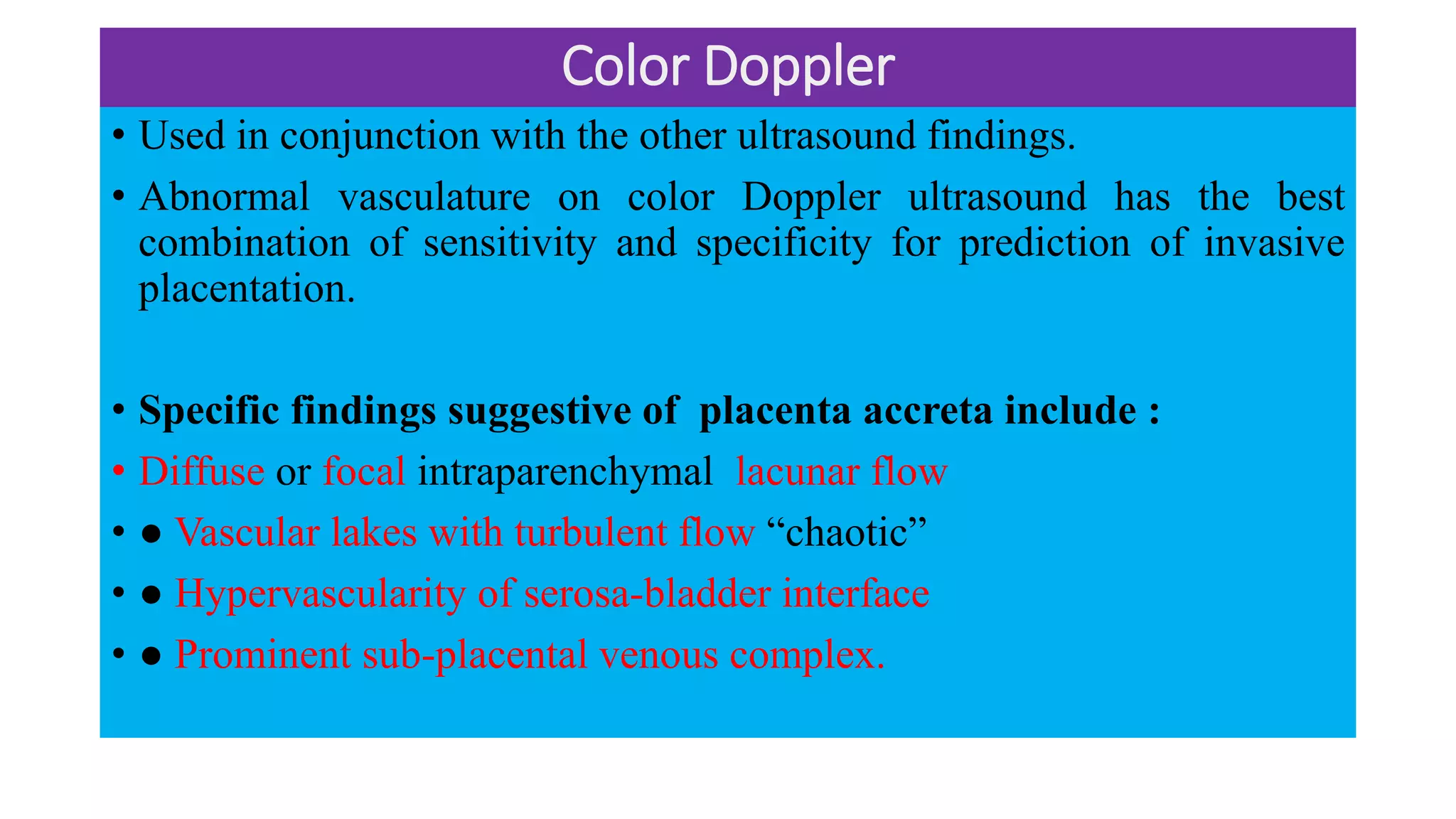

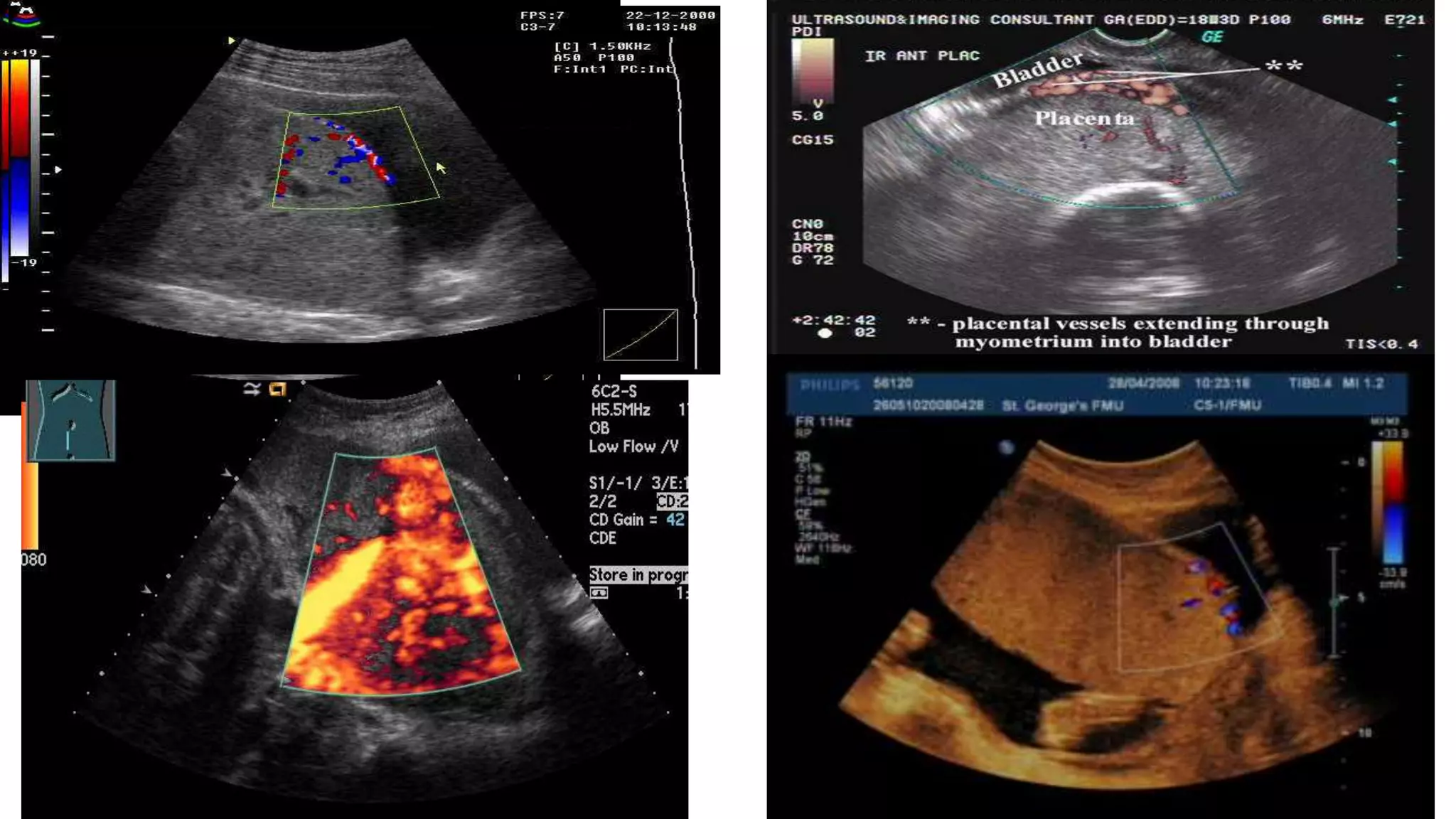

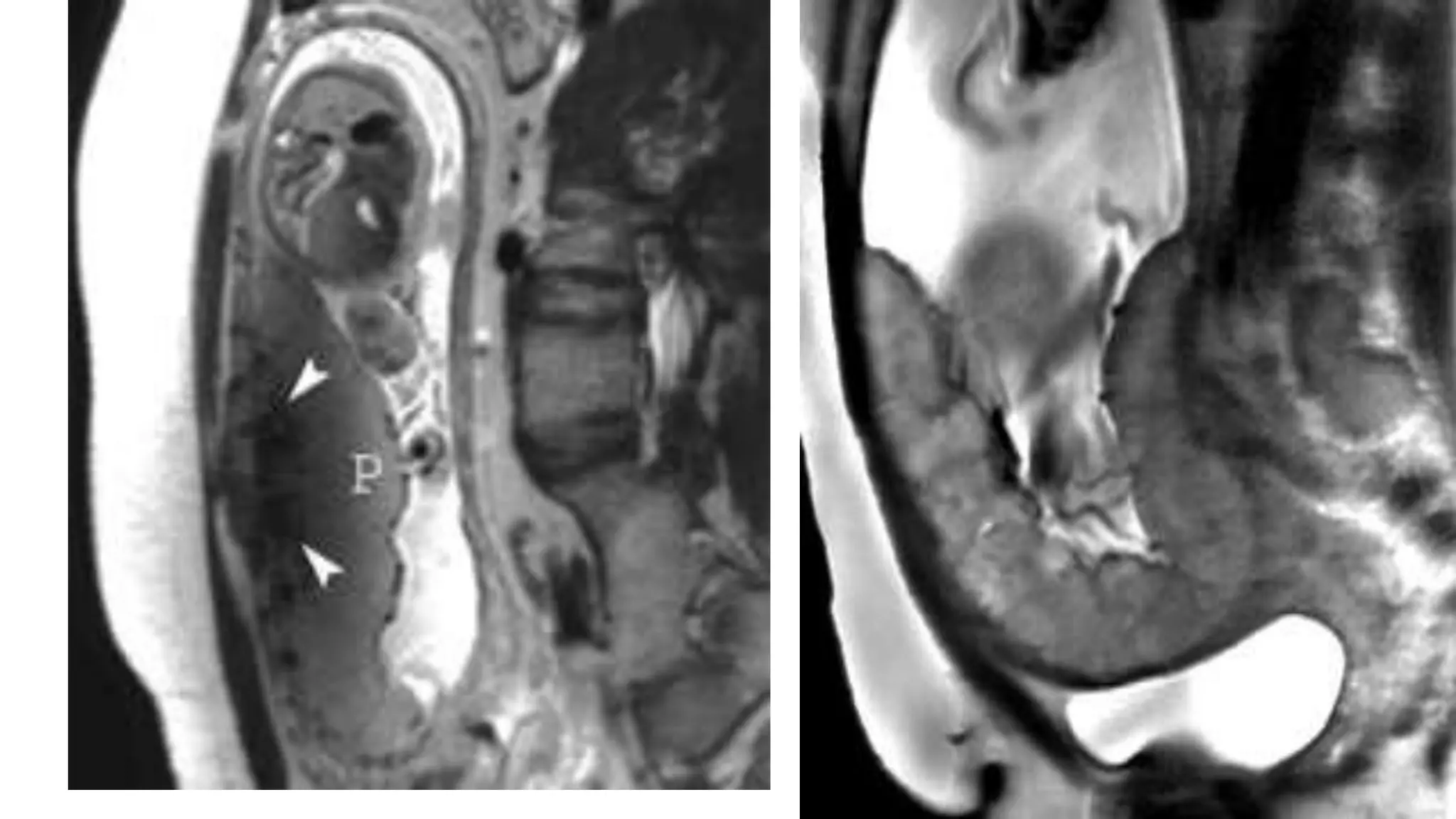

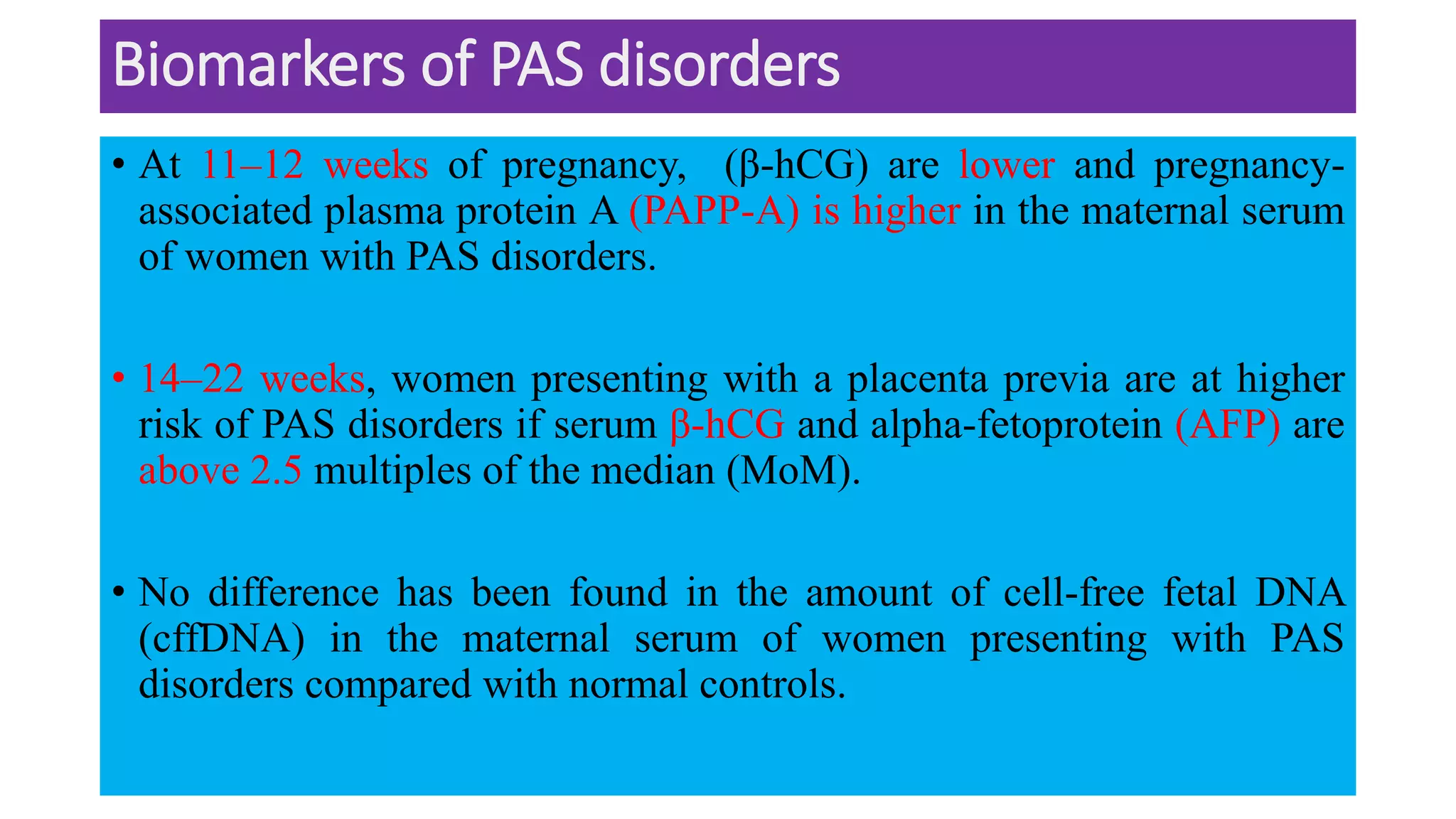

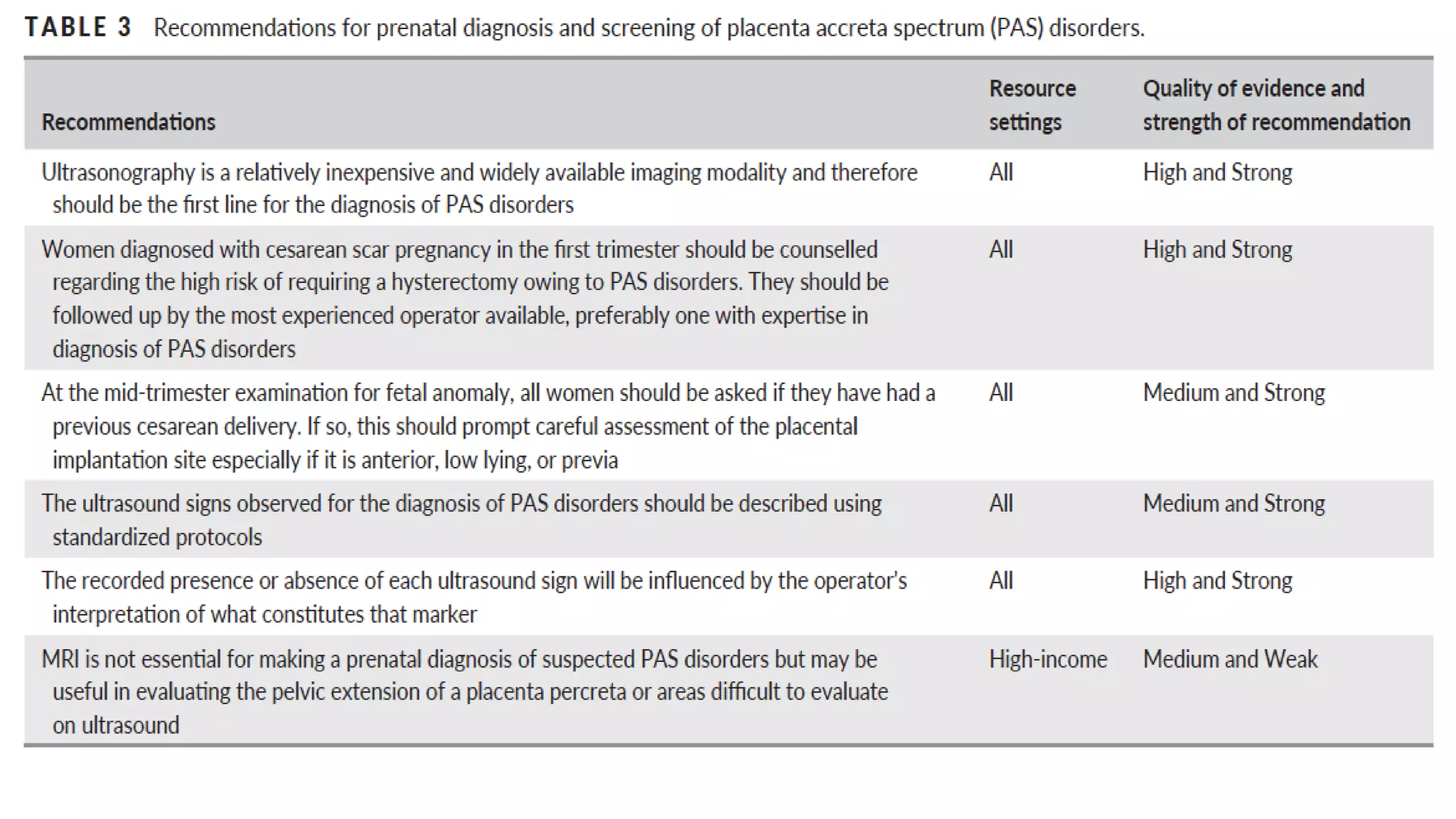

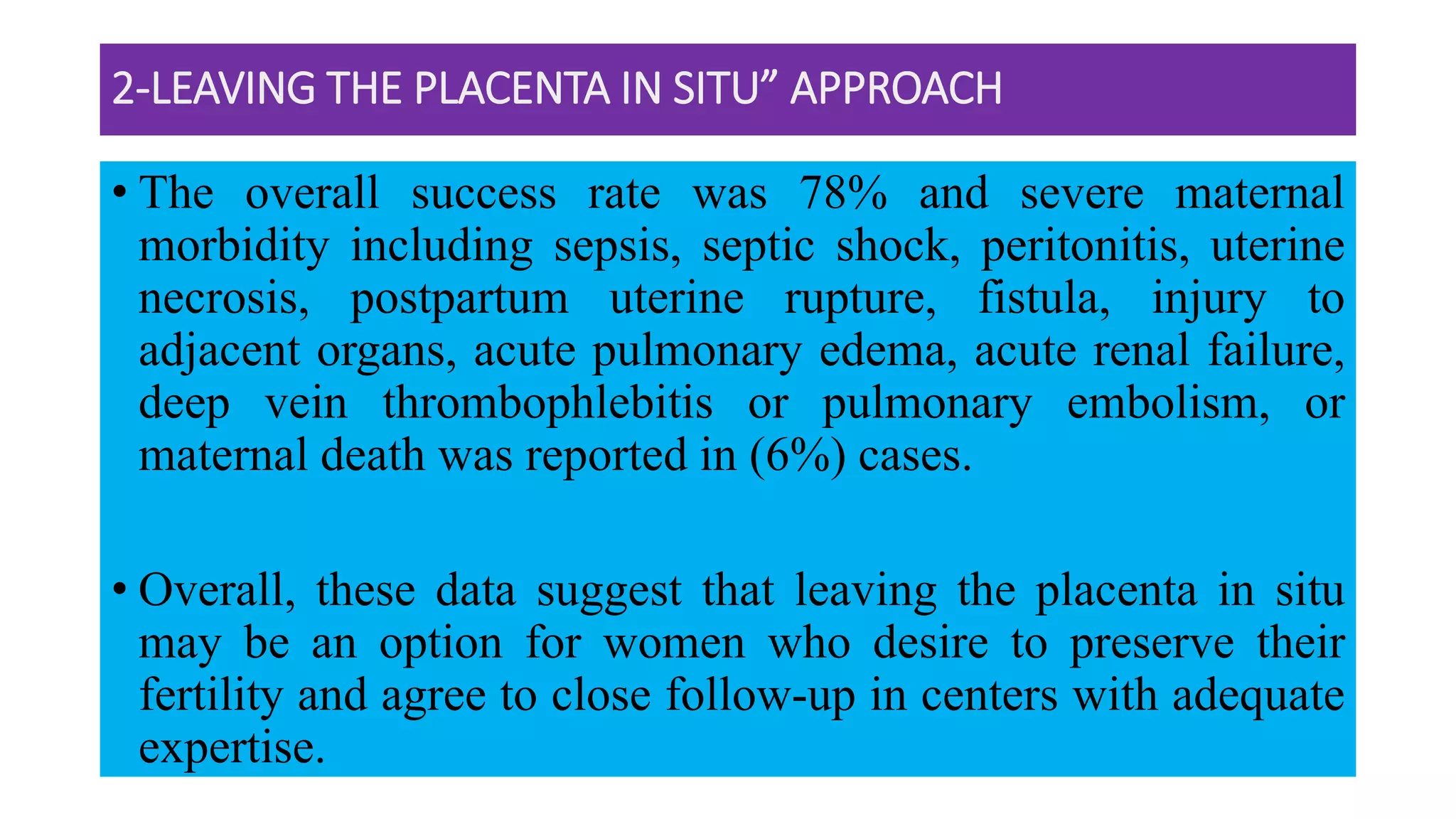

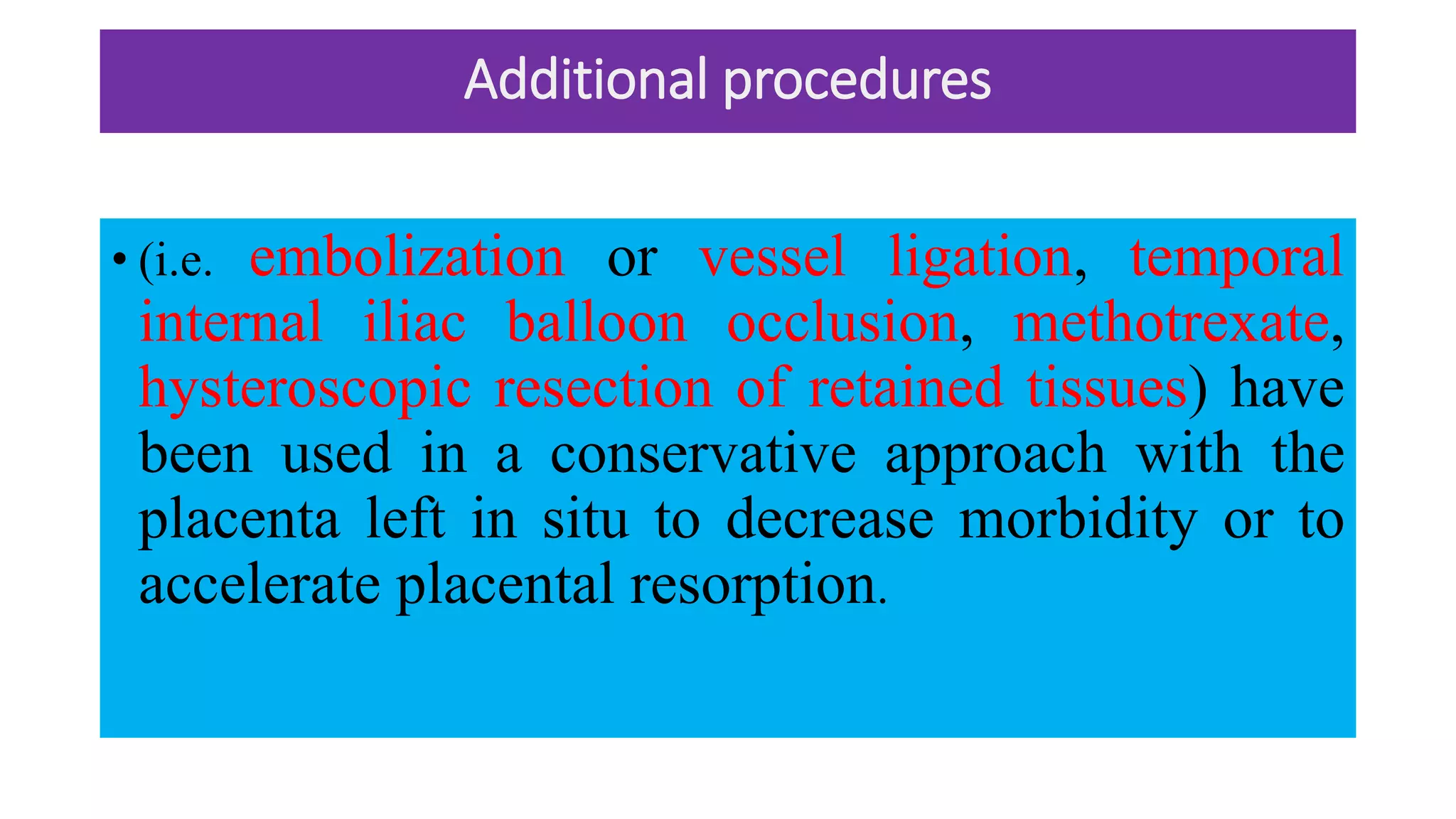

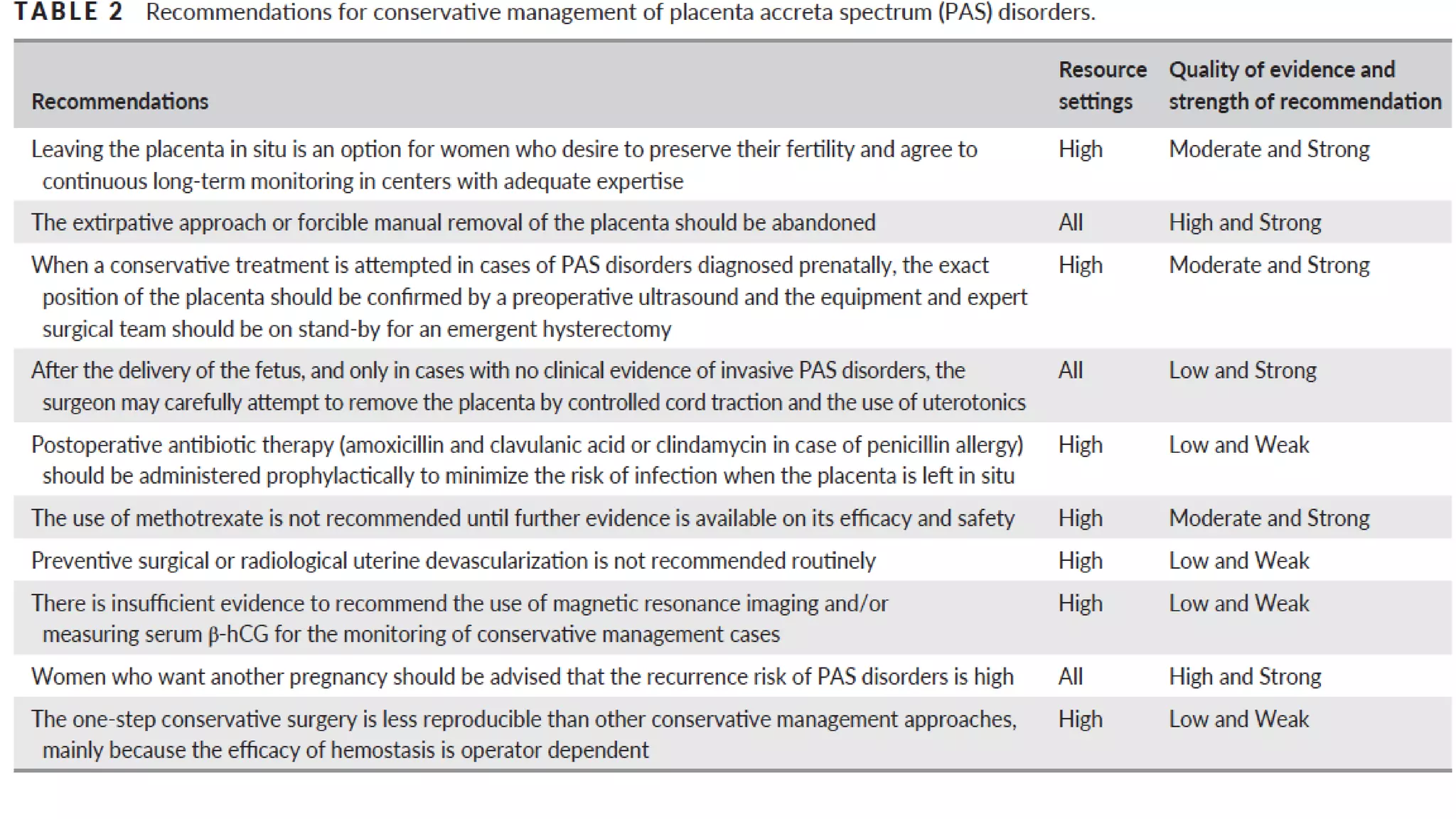

This document provides an overview of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorders, including definitions, epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, prenatal diagnosis, and management. PAS disorders describe abnormal placentation that can range from superficial to deep invasion of the placenta into the uterine wall. Risk factors include placenta previa, cesarean sections, and uterine surgeries. Prenatal ultrasound and MRI can detect signs such as placental lacunae and vascular abnormalities. Left untreated, PAS disorders can lead to life-threatening hemorrhage.