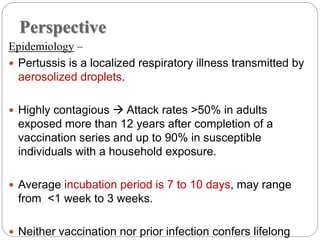

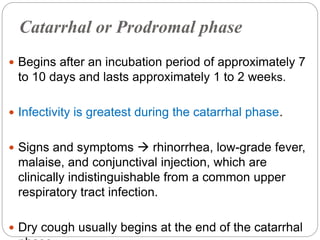

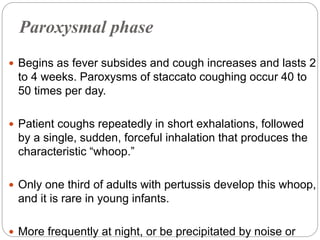

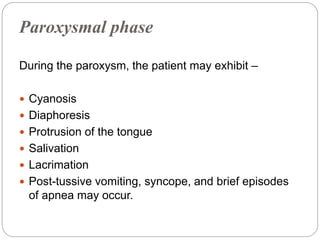

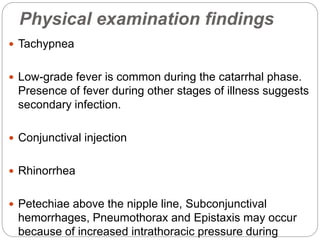

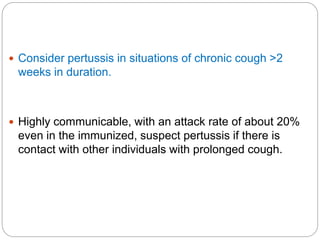

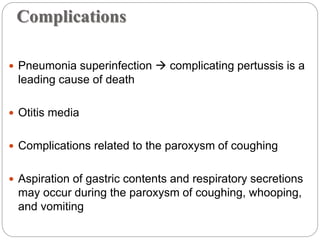

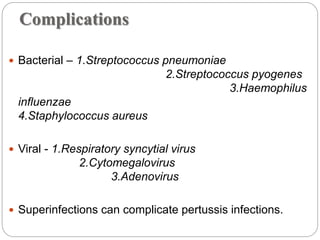

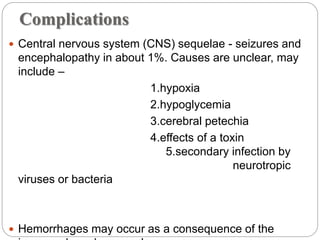

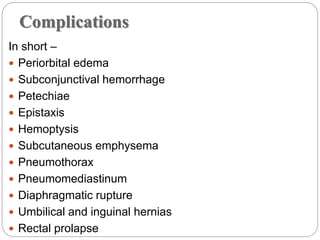

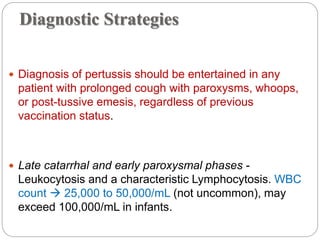

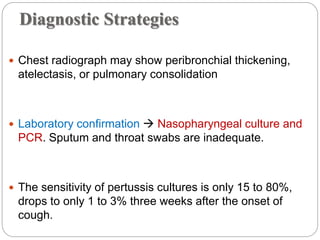

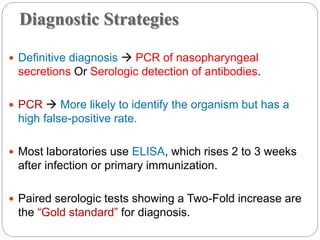

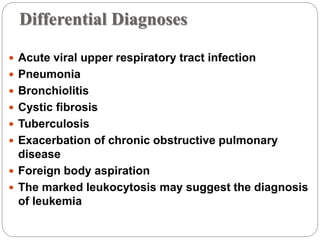

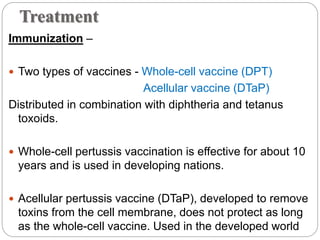

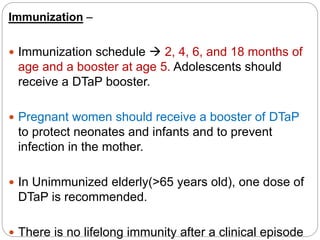

This document provides an overview of pertussis (whooping cough) including its epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment and post-exposure prophylaxis. Pertussis is caused by Bordetella pertussis and presents in three stages - catarrhal, paroxysmal and convalescent. It is highly contagious and vaccination is the primary prevention. For treatment, supportive care and macrolide antibiotics are recommended to reduce infectivity. Post-exposure prophylaxis with antibiotics may be considered for at-risk contacts.