This document provides an overview of writing as a process in language study. It discusses the importance of writing and defines writing as a complex and cognitively demanding activity. It notes that to be successful writers, students need an understanding of writing components and strategies. The document then examines the nature of writing as a process involving various activities. It analyzes key writing components to increase awareness of what occurs when students create written texts. It also discusses the value of writing and differentiates between writing in first and second languages. Specifically, it outlines five main groups of second language learners and notes that factors like age, education level, language similarity, and need determine writing ability in a second language.

![7

in spoken contexts, but at the same time expression is often more complex in its

syntax and more varied in its vocabulary.

Since writing is a complex and cognitively demanding activity, to be

successful, writers need an understanding of the components of a quality

test as well as knowledge of writing strategies that can be used to shape

and organize the writing process. The following subchapters examine the

nature of writing as a process which involves a variety of activities, as well

as analyse writing components in order to increase the reader’s awareness

of what appears to happen when a student attempts to create a written text.

[31, pp.10-16]

§1.1 The Importance of Writing

The ability to write effectively is becoming increasingly important in our

global community, and instruction in writing is thus assuming an increasing role in

foreign-language education. As advances in transportation and technology allow

people from nations and cultures throughout the world to interact with each other,

communications across languages becomes ever more essentials. As a result, the

ability to speak and write a second language is becoming widely recognized as an

important skill for educational, business, and personal reasons. Writing has also

become more important as tenets of communicative language teaching-that is,

teaching language as a system of communication rather than as an object of study-

have taken hold in both second-and foreign-language settings. The traditional view

in language classes that writing functions primarily to support and reinforce

patterns of oral language use, grammar, and vocabulary, is being supplanted by the

notion that writing in a second language is a worthwhile enterprise in and of itself.

Wherever the acquisition of a specific language skill is seen as important, it

becomes equally important to test that skill, and writing is no exception. Thus, as

the role of writing in second- language education increases, there is an ever greater

demand for valid and reliable way to test writing ability, both for classroom use](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-7-2048.jpg)

![8

and as a predictor of future professional or academic success. Writing is put by

people in different situations are so varied that no single definition can cover all

situations. For example, the ability to write down exactly what someone else says

is quite different from the ability to write a persuasive argument. Instead of

attempting an all-encompassing definition, then, it may be more useful to begin by

delineating the situations in which people learn and use second languages in

general and second-language writing in particular, and the types of writing that are

likely to be relevant for second-language writers. While virtually all children are

able to speak their native language when they begin school, writing must be

explicitly taught. Furthermore, in comparison to speaking, listening, and reading,

writing outside of school settings is relatively rare, and extensive public writing is

reserved for those employed in specialized careers such as education, law, or

journalism. In first-language settings, the ability to write well has a very close

relationship to academic and professional success.

Writing as compared to speaking, can be seen as a more standardized system

which must be acquired through special instruction. Mastery of this standard

system is an important prerequisite of cultural and educational participation and the

maintenance of one‘s rights and duties. The fact that writing is more standardized

than speaking allows for a higher degree of sanctions when people deviate from

that standard. Thus, in first-language education, learning to write involves learning

a specialized version of a language already known to students. This specialized

language differs in important ways from spoken language, both in form and use,

but builds upon linguistic resources that students already possess. The ultimate

goal of learning to write is, for most students, to be able to participate fully in

many aspects of society beyond school, and for some, to pursue careers that

involve extensive writing. [52, pp.32-46]

The value of being able to write effectively increases as students‘ progress

through compulsory education on to higher education. At the university level in

particular, writing is seen not just as a standardized system of communication but

also as an essential tool for learning. At least in the English-speaking world one of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-8-2048.jpg)

![9

the main functions of writing at higher levels of education is to expand one‘s own

knowledge through reflection rather than simply to communicate information.

Writing and critical thinking are seen as closely linked, and expertise in writing is

seen as an indication that students have mastered the cognitive skills required for

university work. Or to phrase it somewhat more negatively, a perceived lack of

writing expertise is frequently seen as a sign that students do not possess the

appropriate thinking and reasoning skills that they need to succeed. In first-

language writing instruction, therefore, particularly in higher education, a great

deal of emphasis is placed on originality of thought, the development of ideas, and

the soundness of the writer‘s logic. Conventions of language {voice, tone, style,

accuracy, mechanics} are important as well, but frequently these are seen as

secondary matters, to be addressed after matters of content and organization. While

the specific goals of writing instruction may vary from culture to culture, it is clear

that writing is an important part of the curriculum in schools from earliest grades

onward, and that most children in countries that have a formal education system

will learn to write, at least at a basic level, in that setting. In this sense, we can say

that first language writing instruction is relatively standardized within a particular

culture. [27, pp.44-61]

In contrast, the same cannot be said of second-language writing because of

the wide variety of situations in which people learn and use second languages, both

as children and as adults, in schools and in other settings. We can distinguish

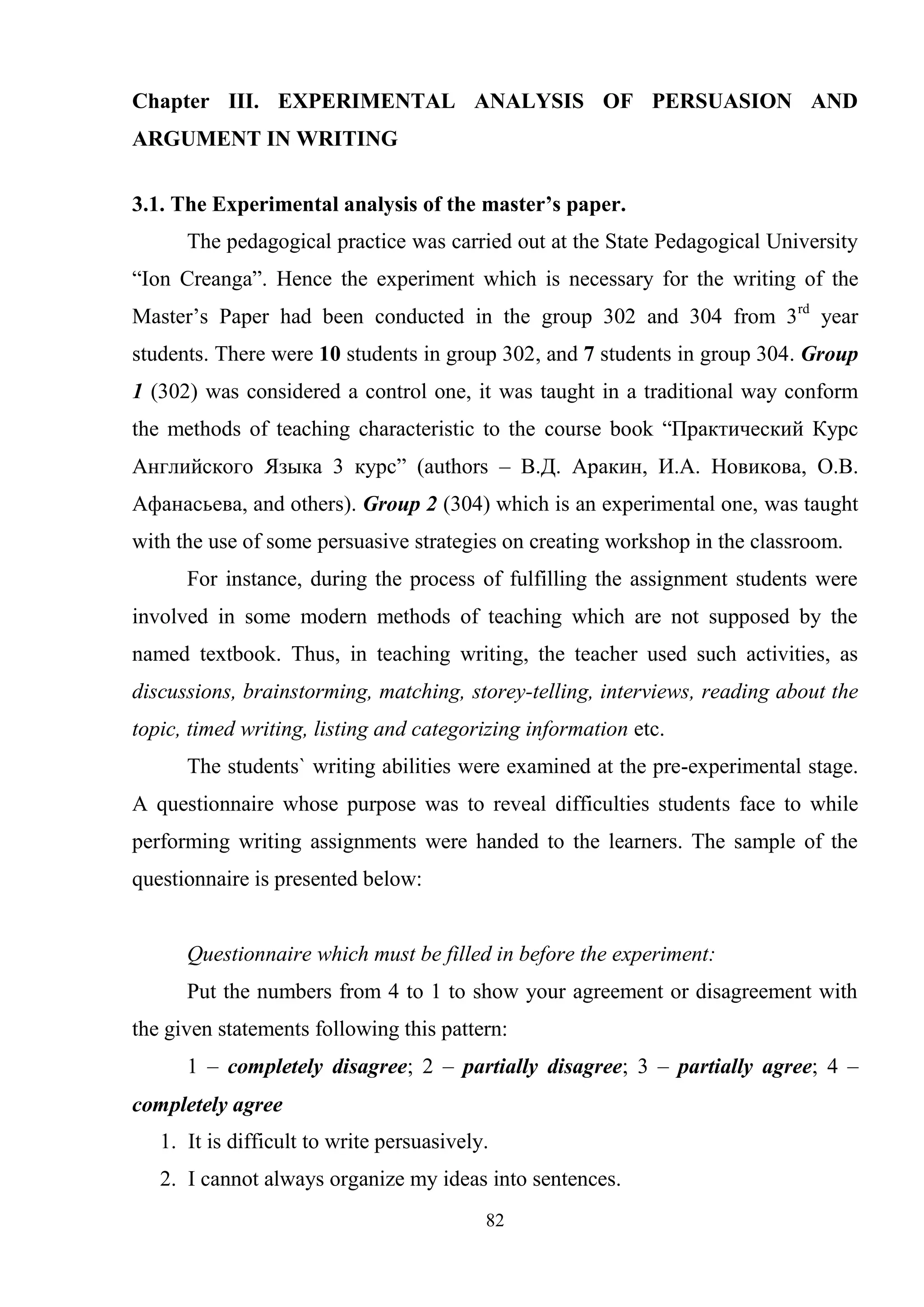

between at least five main groups of second- language learners {adapted from

Bernhardt, 1991}. The first group consists of children from a minority language

group receiving their education in the majority language. These children need to

learn to read and write in a language that is not spoken in their home in order to

succeed in school and ultimately in the workplace. A second group of children are

majority language speakers in immersion programs or otherwise learning a second

language in school. In this case, mastery of the second language enhances their

education but is not critical to ultimate educational success, in contrast to the first

group. A common factor for both groups of children is that their first language id](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-9-2048.jpg)

![11

work smart and hard to acquire them. Only with experience, you can enter the

realm of effective, always-in-demand writers.

Of course, effective writing requires a good command of the language in

which you write or want to write. Once you have that command, you need to learn

some tips and tricks so that you can have an edge over others in this hard-to-

succeed world of writers. There are some gifted writers, granted. But gifted writers

also need to polish their skills frequently in order to stay ahead of competition and

earn their livelihood. [41, pp.212-242]

Good writing stays sharply focused. The writer knows what the subject is,

and never veers far away from that subject. Think of the writer as a rower of a boat

trying to row ashore. That rower must keep his eyes acutely focused on an object

on the shore in order to row straight. If he shifts focus, he'll shift course and miss

the dock. The same holds true for the writer. Good writing is also simple and clear,

one should leave no doubt in the minds of his readers about what he or she is trying

to say to them. Unfortunately, some people seem to forget this principle, especially

when they write.

In academic writing, students struggle to achieve a style of writing that does

not come naturally to them. Learners imagine that they must follow a convoluted

style based on vague impressions of what they read in the scientific literature.

Nothing could be further from the truth and it is here that many of the models that

they use in the literature let them down.

There are just three immutable characteristics of good academic writing that

distinguish it from all other literature. It must always be:

• precise

• clear

• brief

... and in that order.

If it is vague, it is not academic writing; if it is unclear or ambiguous, it is

not academic writing and if it is long winded and unnecessarily discursive, it is

poor academic writing. But precision or clarity should not be sacrificed in order to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-11-2048.jpg)

![12

be brief. So, if it has to take a few more words to make the thoughts crystal clear to

as many readers as possible, then one should use those words. The good news is

that, if one is precise, clear and brief, then he or she does not have to conform to

any other specific rules to be a good scientific writer. The style of academic

writing is plain and simple English, similar to that one would use in a conversation

with a colleague. [30, pp.24-51]

§1.2 Five Steps of Writing

Writing is a complex process that allows writers to explore thoughts and

ideas, and make them visible and concrete. It encourages thinking and learning for

it motivates communication and makes thought available for reflection. When

thought is written down, ideas can be examined, reconsidered, added to,

rearranged, and changed. Writing is most likely to encourage thinking and learning

when students view writing as a process. By recognizing that writing is a recursive

process, and that every writer uses the process in a different way, students

experience less pressure to ‗get it right the first time‘ and are more willing to

experiment, explore, revise, and edit. Yet, novice writers need to practice ‗writing‘

or exercises that involve copying or reproduction of learned material in order to

learn the conventions of spelling, punctuation, grammatical agreement, and the

like. Furthermore, students need to ‗write in the language‘ through engaging in a

variety of grammar practice activities of controlled nature. Finally, they need to

begin to write within a framework ‗flexibility measures‘ that include:

transformation exercises, sentence combining, expansion, embellishments, idea

frames, and similar activities. [59]

Writing may be described as a five-step process: generating ideas,

organizing ideas, writing a draft, revising and rewriting, and proofreading.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-12-2048.jpg)

![13

Generating Ideas

Whatever type of writing a student is attempting, the prewriting stage can

be the most important. This is when students gather their information, and begin to

organize it into a cohesive unit. Prewriting is the most creative step and most

students develop a preferred way to organize their thoughts. Step 1, Generating

Ideas, may be accomplished by using one or more of the following activities:

Freewriting

This term was used by Peter Elbow (Writing Without Teachers, Oxford,

1973) to describe what is essentially free - association writing, where the writer

starts in one direction or another but lets the writing take whatever direction it

seems to want. In freewriting, the teacher sets a page limit or time limit, and then

students simply write about the general topic until the time limit is expired or until

they have met the page limit. Start a class in either composition or literature by

inviting the students to write for five minutes in response to a prompt that has

something directly to do with the day's agenda (What makes writing hard? When is

it easy for you? What is the best [or worst] writing you‘ve ever done? Etc.)

Directions for freewriting are simple and students usually do it easily the

first time they try:

1. Write fast for a limited period of time (five or ten minutes).

2. Don't stop moving your pen or typing on the keyboard to make sure new words

help generate ideas.

3. Write for the whole time period since good ideas often come late in the writing

process.

4. Don‘t worry about spelling, punctuation, organization, or style since you are the

audience.

As learners write, they do not have to worry about spelling, grammar,

punctuation, etc. They simply write down whatever comes to mind regarding the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-13-2048.jpg)

![16

remember to select an appropriate number of details to accomplish your purpose in

writing. You should also ensure your supporting details are specific, relevant, and

typical. Then, arrange the selected details in a reasonable order. If you are writing

a narrative essay, then arrange details in chronological order. If you are writing a

descriptive essay, then spatial (geographical) order may be best (e.g. left-to-right,

top-to-bottom, near-to-far, etc.). For a persuasive essay, arranging details

according to importance (least-to-most or most-to-least) may work best. When

working with examples, work from general to specific or from least complex to

most complex.

Writing the First Draft

The actual writing stage is essentially just an extension of the prewriting

process. The student transfers the information they have gathered and organized

into a traditional format. This may take the shape of a simple paragraph, a one-

page essay, or a multi-page report. Up until this stage, they may not be exactly

certain which direction their ideas will go, but this stage allows them to settle on

the course the paper will take. Teaching about writing can sometimes be as simple

as evaluation good literature together, and exploring what makes the piece

enjoyable or effective. It also involves helping a student choose topics for writing

based on their personal interests. Modeling the writing process in front of your

child also helps them see that even adults struggle for words and have to work at

putting ideas together. [20, p.38]

Unlike freewriting or journal writing, the writers aim drafts at audiences

other than themselves. Most drafting is done by a writer alone, most often outside

of class-- though sometimes class time is allotted for writers to start or work on

drafts in class—a quiet, supportive environment. It is fair to expect early drafts to

be rough; when reading these, instructors usually attend to larger intentions (topic,

organization, evidence) and skip over surface problems (spelling, punctuation,

wordiness), since students will go beyond these language constructions in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-16-2048.jpg)

![19

involvement with a single topic that lets a writer master and advance that topic--

and in the process learn the tricks of the writer's trade.

Revision is conceptual work. It is attending to the larger conceptual matters of

writing: organization, ideas, how an argument works, whether it's well supported,

what to include and exclude from a paragraph or paper. Editing is primarily

sentence level work, making sure that ideas are articulated clearly, precisely, and

correctly for a given audience.

Revising, or editing is usually the least favorite stage of the writing process,

especially for beginning writers. Critiquing one‘s own writing can easily create

tension and frustration. But as you support your young writers, remind them that

even the most celebrated authors spend the majority of their time on this stage of

the writing process. Revising can include adding, deleting, rearranging and

substituting words, sentences, and even entire paragraphs to make their writing

more accurately represent their ideas. It is often not a one-time event, but a

continual process as the paper progresses. When teaching revision, be sure to allow

your child time to voice aloud the problems they see in their writing. This may be

very difficult for some children, especially sensitive ones, so allow them to start

with something small, such as replacing some passive verbs in their paper with

more active ones. [69]

Proofreading

In the fifth step in the writing process, Proofreading, check for errors with

mechanics. Your final essay is to be in Standard English form, so you should

review it a final time to ensure it does not contain any errors in English usage.

Run-on sentences and fragments should be eliminated. You should also ensure

there are no errors in spelling, punctuation, grammar, and capitalization. [54]

Proofreading - is a chance for the writer to scan his or her paper for

mistakes in grammar, punctuation, and spelling. Although it can be tempting for

parents to perform this stage of the writing process for the child, it is important that](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-19-2048.jpg)

![20

they gain proofreading skills for themselves as this improves a student‘s writing

over time. And because children want their writing to be effective, this can actually

be the most opportune to teach some of the standard rules of grammar and

punctuation. When students learn the rules of mechanics during the writing process

they are much more likely to remember to use them in the future. [1, pp.48-62]

§1.3 Principles of Effective Writing

Writing is the art of making an utterance perfectly natural through the

perfectly unnatural process of making every word and phrase again and again,

cutting here and adding there, until it is just so. It is contrived spontaneity. What

the writer wants is something just like speech only more compressed, more

melodic, more economical, more balanced, more precise.

According to Aristotle: ―To write well, express yourself like the common

people, but think like a wise man.‖ What makes a good writer is that he knows the

difference between those of his sentences that work and those that don‘t; between

those he gets nearly right and those he nails; between those that sing and swing and

those that mumble and fail. Sentences fail for many reasons. You may not know

enough about what a sentence is, for instance, to reach the end with poise. Or you

may know more than enough, but you give them too much weight to carry; you

work them too hard. And they break. [18, pp.3-55]

Students must express their ideas clearly, concisely, and completely when

speaking and writing. If their written messages aren't clear or lack important

details, people will be confused and will not know how to respond. In addition, if

their written messages are too lengthy, people simply don't read them.

The process of good writing involves three basic steps - preparing, writing, and

editing. Practicing the following 16 principles will help anyone be a more effective

writer.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-20-2048.jpg)

![25

spelling and making sure the use of words is correct, and also have links to lots of

other resources.

Good writers take almost too much care with their work. This led Thomas

Mann to say that ―a writer is somebody for whom writing is more difficult than it

is for other people‖. To be a writer you don‘t have to be the smartest soul on earth;

you don‘t have to know the biggest words. You just have to commit yourself to

saying what it is you have to say as clearly as you can manage; you have to listen

to it and remake it till it sounds like you at your best; you just have to make

yourself hard to please, word after word. Until you make it seem easy. Work hard

to make your writing seem to have cost you no effort at all. Struggle gamely to

make it seem that your words came as naturally to you as the sun to the sky in the

morning. Just as though you opened your mouth and spoke. ―The end of all

method,‖ said Zeno, ―is to seem to have no method at all.‖ [26, pp.43-59]

Of all the arts writing is the most vulgar — and the least like art. It makes art

out of words, out of the stuff we conduct our lives in: it makes art, not out of paint

or textiles, but out of speech, out of what we use to buy the paper and scold the

children and write the report. The best writing sounds just like speech, only better.

Good writing is a transcendent kind of talking. But because writing isn‘t, in fact,

speaking, we have to take more care with it: writing lasts, and we have only the

words with which to make our point and strike our tone. [23, pp.24-52]

To overcome the fear that you don‘t know how to write, the best thing to do

is the most important writing step of all — start writing, uncomfortable though it

may feel, as though you were talking. Don‘t think of it as writing at all — think of

it as talking on paper, and start talking with your fingers. Once you‘ve tricked

yourself into trusting the words your ―speaking mind‖ suggests, once you‘ve

stopped thinking about it as writing, you‘ll be surprised how much more easily the

writing comes to you, and how much better it works.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-25-2048.jpg)

![26

Writing, as Carol Gelderman put it, is the most exact form of thinking. It

exacts — from those of us who want to do it well — precision, discernment,

fineness of observation and detachment. By its nature, true writing practices

critical thinking. ‗Critical’ has come to mean to most people something like

―negative.‖ It also means ―very important.‖ But its primary meaning is ―exacting,‖

―skeptical,‖ ―disinterested,‖ ―discerning,‖ ―analytical.‖ We take it from the Greek

word ‗kritikos’, meaning ―one who is skilled in judging; one who takes things

apart.‖ The writer is the ‗kritikos’, but she‘s also skilled at putting things back

together again. Good, sustained critical thinking underlies good, clear writing: you

could almost say that good writing is critical thinking. It is critical thinking

resolved and put down on paper — elegantly.

―What you‘re saying is that you want it said short and right and nice.‖ The

sentences, though they may still work, lose their life and their capacity to inform,

let alone delight, anyone, including ourselves, who makes them. The shapelier and

elegant one‘s sentences are, the sounder they are structurally, the better one‘s

writing will be. The leaner and clearer and livelier one‘s sentences are, the bigger

is their effect and paragraphs will simply rock and roll. Writing is both creativity

and discipline; it is freedom within bounds. You need to know the constraints in

order to know how to be free within them. [38, p.37-88]

Summing all up, one doesn't have to be a great writer to be successful.

However, he or she must be able to clearly and succinctly explain his/hers thoughts

and ideas in writing. Strive to be simple, clear, and brief. Like any skill,

"good writing" requires practice, feedback, and ongoing improvement.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-26-2048.jpg)

![27

Chapter II. PERSUASION AND ARGUMENT IN WRTITING

Every day we are confronted by persuasion. Food makers want us to buy

their newest products, while movie studios want us to go see the latest

blockbusters. Because persuasion is such a pervasive component of our lives, it is

easy to overlook how we are influenced by outside sources. Due to the usefulness

of influence, persuasion techniques have been studied and observed since ancient

times, but social psychologists began formally studying these techniques early in

the 20th-century. The goal of persuasion is to convince the target to internalize the

persuasive argument and adopt this new attitude as a part of their core belief

system. When we think of persuasion, negative examples are often the first to

come to mind, but persuasion can also be used as a positive force. Public service

campaigns that urge people to recycle or quit smoking are great examples of

persuasion used to improve people‘s lives. [55]

Every single human requires the art of persuasion at some point in their

lives. As a child, one might use persuasion for the attainment of a toy or as an adult

for the acquiring of other objects. A person might whine, throw tantrums, but this

behavior never seems to attain what is wanted by the person and just makes things

worse. What one needs is persuasion as it is the only method that can be pursued

by one to achieve what he wants. While the art and science of persuasion has been

of interest since the time of the Ancient Greeks, there are significant differences

between how persuasion occurs today and how it has occurred in the past. [70]

In his book The Dynamics of Persuasion: Communication and Attitudes in

the 21st Century, Richard M. Perloff outlines the five major ways in which modern

persuasion differs from the past:

1. The number of persuasive message has grown tremendously. Think for a

moment about how many advertisements you encounter on a daily basis.

According to various sources, the number of advertisements the average U.S.

adult is exposed to each day ranges from around 300 to over 3,000.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-27-2048.jpg)

![28

2. Persuasive communication travels far more rapidly. Television, radio and

the Internet all help spread persuasive messages very quickly.

3. Persuasion is big business. In addition to the companies that are in business

purely for persuasive purposes (such as advertising agencies, marketing firms,

public relations companies), many other business are reliant on persuasion to

sell goods and services.

4. Contemporary persuasion is much more subtle. Of course, there are plenty

of ads that use very obvious persuasive strategies, but many messages are far

more subtle. For example, businesses sometimes carefully craft very specific

image designed to urge viewers to buy products or services in order to attain

that projected lifestyle.

5. Persuasion is more complex. Consumers are more diverse and have more

choices, so marketers have to be savvier when it comes to selecting their

persuasive medium and message. [32, pp.45-58]

All of the written texts have to a greater or lesser degree stressed persuasion,

or what language scholars call rhetoric, the use of persuasive language to influence

readers or listeners. For example, asking readers to accept your interpretation of a

description or your idea about how two things compare or contrast involves a mild

form of persuasion even if the discussion is largely factual and objective. So too

does having someone accept your definition of an important idea or term or of

what you think is comparable or analogous to that term. The point is that almost

every form of writing except the listing of purely factual information tries to

persuade the reader to some degree. Furthermore, even a completely objective list

may try to be persuasive if those facts have been carefully selected with the

ultimate goal of changing the reader‘s mind. Imagine a list of ‗top restaurants in

town‘ published by the local restaurant owners association: Would the eateries of

non-members be included? Some less reputable newspapers and magazines do

favorable features stories on establishments in their pages. Persuasion, even in

seemingly objective forms, is all around us.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-28-2048.jpg)

![29

According to definition, ―Persuasion is a form of influence. It is the process

of guiding people toward the adoption of an idea, attitude, or action by rational and

symbolic (though not only logical) means. It is a problem-solving strategy and

relies on ―appeals‖ rather than force‖. Dictionary.com site describes the verb

‗persuade‘ as to induce to believe by appealing to reason or understanding;

convince; a symbolic process in which communicators try to convince other people

to change their attitudes or behaviors regarding an issue through the transmission

of a message in an atmosphere of free choice. Put simply, persuasion is

convincing another person of your conclusions. You want to agree with you, even

champion your cause. The key elements of this definition of persuasion are that:

Persuasion is symbolic, utilizing words, images, sounds, etc

It involves a deliberate attempt to influence others.

Self-persuasion is key. People are not coerced; they are instead free to choose.

Methods of transmitting persuasive messages can occur in a variety of ways,

including verbally and nonverbally via television, radio, Internet or face-to-face

communication. [15, pp.49-78]

Persuasion of the type required in many college and university courses is

similar to these forms of persuasion, but is more forceful, more argumentative.

Tailored definitions, example and classification categories, and carefully chosen

cause/effect relationships are common developmental methods used in persuasive

arguments.

When describing serious writing, the word ‗argument‘ does not mean ‗verbal

disagreement‘ but rather the logical steps or reasons given in support of a position

or a series of statements or ideas in an essay or a discussion. In formal writing and

in oral presentations in law courts, in scientific and medical seminars, and in

formal business meetings, a special discipline is imposed on discussions. The

discipline is the discipline of argument or argumentation, and its purpose is to

discover the truth or at least the closest possible approximation to the truth.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-29-2048.jpg)

![31

Rhetorical modes are based on the ways human brains process information.

Choosing the one mode that matches your topic helps you organize your writing

and helps the reader process the information you want to discuss. Using key words

that emphasize the chosen mode helps reinforce your essay's coherence.

[19, pp.24-67]

What is Persuasive Writing?

The purpose of persuasive writing is to convince the reader to accept a

particular point of view or to take a specific action. If it is important to present

other sides of an issue, the writer does so, but in a way that makes his or her

position clear. The unmistakable purpose of this type of writing is to convince the

reader of something. In well-written persuasion, the topic or issue is clearly stated

and elaborated as necessary to indicate understanding and conviction on the part of

the writer. [60]

Persuasive writers use persuasion to make people conform to their ideas that

he or she presents in his work. To write persuasively, first of all the writer needs to

have an argument. The argument has to be one-sided and the other side of the

argument or the opposite answer is disregarded, but another fact is that persuasive

writing is never related to the pros and cons of the topic, but general facts related to

its factuality. According to sources, ―It can‘t be a fact. If you were to choose as

your topic, ―Vipers are dangerous,‖ you wouldn‘t have to persuade anyone of that.

However, if your topic was, ―Vipers should be eliminated from the animal

kingdom,‖ then you would have presented an opinion that could be debated. Your

persuasive work/essay will focus on only one side–your chosen side–of the

argument. This will not be a pros-and-cons essay. Also, it won‘t be a personal

opinion essay. You must be prepared to back up your logic with evidence collected

in research that supports your position‖. [74]

Persuasive writing moves the reader to take an action or to form or change

an opinion. This type of writing is assessed for three reasons:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-31-2048.jpg)

![38

society.

Conclusion: Therefore, minimum wage should be increased.

Once the syllogism has been determined, the author needs to elaborate each step in

writing that provides evidence for the premises:

The purpose of minimum wage is to ensure that workers can provide basic

amenities to themselves and their families. A report in the Journal of

Economic Studies indicated that workers cannot live above the poverty line

when minimum wage is not proportionate with the cost of living. It is

beneficial to society and individuals for a minimum wage to match living

costs.

Unfortunately, our state's minimum wage no longer reflects an increasing

cost of living. When the minimum wage was last set at $5.85, the yearly

salary of $12,168 guaranteed by this wage was already below the poverty

line. Years later, after inflation has consistently raised the cost of living,

workers earning minimum wage must struggle to support a family, often

taking 2 or 3 jobs just to make ends meet. 35% of our state's poor population

is made up of people with full time minimum wage jobs.

In order to remedy this problem and support the workers of this state,

minimum wage must be increased. A modest increase could help alleviate

the burden placed on the many residents who work too hard for too little just

to make ends meet.

This piece explicitly states each logical premise in order, allowing them to build to

their conclusion. Evidence is provided for each premise, and the conclusion is

closely related to the premises and evidence. Notice, however, that even though

this argument is logical, it is not irrefutable. An opponent with a different

perspective and logical premises could challenge this argument. [28, pp.74-98]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-38-2048.jpg)

![40

Proofread the argument. Too many careless grammar mistakes cast doubt on

your character as a writer.

According to Aristotle, writers can invent a character suitable to an occasion--

this is invented ethos. However, if writers are fortunate enough to enjoy a good

reputation in the community, they can use it as an ethical proof--this is situated

ethos. [11, pp. 18-34]

The status of ethos in the hierarchy of rhetorical principles has fluctuated as

rhetoricians in different eras have tended to define rhetoric in terms of either

idealistic aims or pragmatic skills. For Plato the reality of the speaker's virtue is

presented as a prerequisite to effective speaking. In contrast,

Aristotle's Rhetoric presents rhetoric as a strategic art which facilitates decisions in

civil matters and accepts the appearance of goodness as sufficient to inspire

conviction in hearers. The contrasting views of Cicero and Quintilian about the

aims of rhetoric and the function of ethos are reminiscent of Plato's and Aristotle's

differences of opinion about whether or not moral virtue in the speaker is intrinsic

and prerequisite or selected and strategically presented. [10, pp.28-32]

If Aristotle's study of pathos is a psychology of emotion, then his treatment

of ethos amounts to sociology of character. It is not simply a how-to guide to

establishing one's credibility with an audience, but rather it is a careful study of

what Athenians consider to be the qualities of a trustworthy individual. [21, p.45]

Some types of oratory may rely more heavily on one type of proof than another.

Today, for example, we note that a great deal of advertising uses ethos extensively

through celebrity endorsements, but it might not use pathos. It is clear from

Aristotle's discussion in Rhetoric, however, that, overall, the three proofs work in

conjunction to persuade. Moreover, it is equally clear that ethical character is the

lynch pin that holds everything together. As Aristotle stated, 'moral character …

constitutes the most effective means of proof'. An audience is just not likely to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-40-2048.jpg)

![41

respond positively to a speaker of bad character: His or her statement

of premises will be met with skepticism; he or she will find it difficult to rouse the

emotions appropriate to the situation; and the quality of the speech itself will be

viewed negatively. [49, pp.22-46]

Fundamental to the Aristotelian concept of ethos is the ethical principle of

voluntary choice: the speaker's intelligence, character, and qualities comprehended

by good will are evidenced through invention, style, delivery, and likewise

incorporated in the arrangement of the speech. Ethos is primarily developed by

Aristotle as a function of rhetorical invention; secondarily, through style and

delivery. [61]

The appeal of our good character can occur on one or more of the following

levels in any given argument:

Are you a reasonable person? (That is, are you willing to listen, compromise,

concede points?)

Are you authoritative? (Are you experienced and/or knowledgeable in the field

you are arguing in?)

Are you an ethical/moral person (Is what you're arguing for ethically

sound/morally right)

Are you concerned for the well-being of your audience? (To what extent will

you benefit as a result of arguing from your particular position?)

The ethical appeal is based on the audience's perception of the speaker.

Therefore, the audience must trust the speaker in order to accept the arguments.

Don't overlook ethical appeal, as it can be the most effective of the three.

Example of ethos:

If, in my low moments, in word, deed or attitude, through some error of

temper, taste, or tone, I have caused anyone discomfort, created pain, or

revived someone's fears, that was not my truest self. If there were occasions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-41-2048.jpg)

![42

when my grape turned into a raisin and my joy bell lost its resonance, please

forgive me. Charge it to my head and not to my heart. My head - so limited

in its finitude; my heart, which is boundless in its love for the human family.

I am not a perfect servant. I am a public servant doing my best against the

odds." (Jesse Jackson, Democratic National Convention

Keynote Address, 1984)

✦Pathos

Pathos, or emotional appeal, appeals to an audience's needs, values, and

emotional sensibilities.

Argument emphasizes reason, but used properly there is often a place for

emotion as well. Emotional appeals can use sources such as interviews and

individual stories to paint a more legitimate and moving picture of reality or

illuminate the truth. For example, telling the story of a single child who has been

abused may make for a more persuasive argument than simply the number of

children abused each year because it would give a human face to the numbers.

The logical appeal is certainly an extremely persuasive tool. However, our

human nature also lets us be influenced by our emotions. Emotions range from

mild to intense; some, such as well-being, are gentle attitudes and outlooks, while

others, such as sudden fury, are so intense that they overwhelm rational

thought. Images are particularly effective in arousing emotions, whether those

images are visual and direct as sensations, or cognitive and indirect as memory or

imagination, and part of a writer's task is to associate the subject with such images.

[24, pp.128-136]

Example (to my father who smokes): "I remember when Grandma died of

lung cancer. It was the first time I had ever seen you cry Dad. I remember that you

also made me promise not to start smoking." You could also offer vivid examples](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-42-2048.jpg)

![43

in support of your argument. Use language and images that are emotionally

charged:

You might detail the pain of going through chemo therapy.

You could use Xrays of diseased lungs, or photos of cancerous gums.

Be careful, however, that when you use emotional appeal, you use it

"legitimately." James D. Lester states that ―raw emotion cannot win the day

against opponents who demand factual evidence, yet the dull recitation of

statistical facts may be meaningless unless you motivate readers and get them

involved.‖ You should not use it as a substitute for logical and/or ethical appeals.

Don't use emotional appeals to draw on stereotypes or manipulate our emotional

fears. Don't use emotional appeal to get an automatic, knee-jerk reaction from

someone. If you use emotionally charged language or examples simply to upset or

anger an audience, you are using emotion illegitimately. Your use of emotional

appeal shouldn't oversimplify a complicated issue. [65]

"The man who can carry the judge with him, and put him in whatever frame

of mind he wishes, whose words move men to tears or anger, has always been a

rare creature. Yet this is what dominates the courts, this is the eloquence that reigns

supreme. . . . Where force has to be brought to bear on the judges' feelings and

their minds distracted from the truth, there the orator's true work begins." taken

from Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria, c. 95 A.D.

Hillary Clinton used a moment of brilliantly staged emotion to win the New

Hampshire Democratic primary. As she answered questions in a diner on the

morning before the election, Mrs. Clinton's voice began to waver and crack when

she said: 'It's not easy. This is very personal for me.' Emotions can be an

electoral trump card, especially if one can show them as Mrs. Clinton did, without

tears. The key is to appear stirred without appearing weak. [62]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-43-2048.jpg)

![44

It is perilous to announce to an audience that we are going to play on the

emotions. As soon as we apprise an audience of such an intention, we jeopardize, if

we do not entirely destroy, the effectiveness of the emotional appeal. It is not so

with appeals to the understanding. [57]

A brilliant young woman was asked once to support her argument in favor

of social welfare. She named the most powerful source imaginable: the look in a

mother's face when she cannot feed her children. Can you look that hungry child in

the eyes? See the blood on his feet from working barefoot in the cotton fields. Or

do you ask his baby sister with her belly swollen from hunger if she cares about

her daddy's work ethics?

Only use an emotional appeal if it truly supports the claim you are making,

not as a way to distract from the real issues of debate. An argument should never

use emotion to misrepresent the topic or frighten people.

Emotional and ethical appeals prompt your audience to care about an issue

on more than an intellectual level. As with introductions, conclusions are an

excellent place to do this because it reminds your audience that your position is not

merely an academic one, but one that has consequences for real people.

Concluding on emotional and ethical grounds provides an opportunity to

strengthen the appeal of you position.

For example:

The safety of our society is directly influenced by the correct handling of our

household hazardous waste. Everyone uses dangerous chemicals every day

and the dangers are astounding when they aren't disposed of in a proper and

professional manner. In an age of many chemicals, we must be careful not to

put each other, our pets, and our environment in harm's way: We do not need

sanitation workers losing their lives or are pets poisoned. In a country with a

population the size of the United States, it is necessary that every

homeowner ensure a healthy environment for everyone-plants and animals

included-by taking precautions when disposing of hazardous waste. It is the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-44-2048.jpg)

![45

job of every responsible citizen to ensure that others are not put at risk when

disposing of chemicals. [64]

Examples of pathos:

"This is the lesson: Never give in. Never give in. Never, never, never, never-

-in nothing, great or small, large or petty--never give in, except to

convictions of honor and good sense. Never yield to force. Never yield to the

apparently overwhelming might of the enemy. We stood all alone a year ago,

and to many countries it seemed that our account was closed, we were

finished. All this tradition of ours, our songs, our School history, this part of

the history of this country, were gone and finished and liquidated. Very

different is the mood today. Britain, other nations thought, had drawn a

sponge across her slate. But instead our country stood in the gap. There was

no flinching and no thought of giving in; and by what seemed almost a

miracle to those outside these Islands, though we ourselves never doubted it,

we now find ourselves in a position where I say that we can be sure that we

have only to persevere to conquer."

Below are three quotes from President Clinton's 1996 State of the Union speech

to consider as an example which includes all three types of appeals. Here Clinton

combines all of the available means of persuasion for his given thesis:

Ethical appeal (ethos)

"Before I go on, I would like to take just a moment to thank my own family,

and to thank the person who has taught me more than anyone else over 25

years about the importance of families and children — a wonderful wife, a

magnificent mother and a great First Lady. Thank you, Hillary" — showing

himself to be a sensitive family man;

Emotional appeal (pathos)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-45-2048.jpg)

![47

To the media, I say you should create movies and CDs and television shows you'd

want your own children and grandchildren to enjoy. I call on Congress to pass the

requirement for a V-chip in TV sets so that parents can screen out programs they

believe are inappropriate for their children. When parents control what their

young children see, that is not censorship; that is enabling parents to assume more

personal responsibility for their children's upbringing. And I urge them to do it.

The V-chip requirement is part of the important telecommunications bill now

pending in this Congress. It has bipartisan support, and I urge you to pass it now.

To make the V-chip work, I challenge the broadcast industry to do what movies

have done — to identify your programming in ways that help parents to protect

their children. And I invite the leaders of major media corporations in the

entertainment industry to come to the White House next month to work with us in

a positive way on concrete ways to improve what our children see on television. I

am ready to work with you." [63]

2.2 Logical Fallacies

Fallacies are common errors in reasoning that will undermine the logic of

your argument. Fallacies can be either illegitimate arguments or irrelevant points,

and are often identified because they lack evidence that supports their claim. Avoid

these common fallacies in your own arguments and watch for them in the

arguments of others.

Slippery slope

This is a conclusion based on the premise that if A happens, then eventually

through a series of small steps, through B, C,..., X, Y, Z will happen, too, basically

equating A and Z. So, if we don't want Z to occur A must not be allowed to occur

either.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-47-2048.jpg)

![49

Genetic Fallacy

A conclusion is based on an argument that the origins of a person, idea,

institute, or theory determine its character, nature, or worth.

Example: The Volkswagen Beetle is an evil car because it was originally

designed by Hitler's army.

In this example the author is equating the character of a car with the

character of the people who built the car.

Begging the Claim

The conclusion that the writer should prove is validated within the claim.

Example: Filthy and polluting coal should be banned.

Arguing that coal pollutes the earth and thus should be banned would be

logical. But the very conclusion that should be proved, that coal causes enough

pollution to warrant banning its use, is already assumed in the claim by referring to

it as "filthy and polluting." [29, pp.165-176]

Circular Argument

This restates the argument rather than actually proving it.

Example: George Bush is a good communicator because he speaks

effectively.

In this example the conclusion that Bush is a "good communicator" and the

evidence used to prove it "he speaks effectively" are basically the same idea.

Specific evidence such as using everyday language, breaking down complex

problems, or illustrating his points with humorous stories would be needed to

prove either half of the sentence.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-49-2048.jpg)

![52

Moral Equivalence

This fallacy compares minor misdeeds with major atrocities.

Example: That parking attendant who gave me a ticket is as bad as Hitler.

In this example, the author is comparing the relatively harmless actions of a

person doing their job with the horrific actions of Hitler. This comparison is unfair

and inaccurate. [12, pp.227-286]

2.3 Types of Evidence

Evidence is the information that helps in the formation of a conclusion or

judgment. Whether we know it or not, we provide evidence in most of our

conversations – they‘re all the things we say to try and support our claims. For

example, when you leave a movie theater, turn to your friend, and say ―That movie

was awesome! Did you see those fight scenes?! Unreal!‖, you have just made a

claim and backed it up.

Evidence is required so as to support the claim made by the writer. The

evidence cannot be general statements but have to be valid with good sources.

Apart from evidence, persuasion needs to be sequential with one fact of the topic

leading to the other for the betterment of the reader, as this would help him or her

in understanding the topic as well as the claim. For example, if one is writing an

essay on the above mentioned statement that is, ―Vipers should be eliminated from

the animal kingdom,‖ the writer needs to begin by the dangers posed by the vipers

and then move on to numerical data as to how much disaster is caused by them and

then carry this argument forward.

The effectiveness of such arguments – whether they are persuasive or not –

depends on two main factors, the credibility of the evidence and the validity of the

argument itself, with ‗validity‘ meaning how well the argument is put together.

Most people think of ―evidence‖ as numbers and quotes from famous](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-52-2048.jpg)

![53

people. While those are valid types of evidence, there are more to choose from

than just statistics and quotes, though. Before you make a choice, review the

points you made and decide if your statements can be backed up by evidence.

Types of evidence include:

Facts - a powerful means of convincing, facts can come from your reading,

observation, or personal experience. Note: Do not confuse facts with truths. A

"truth" is an idea believed by many people, but it cannot be proven. Nancy R.

Comley writes that ―facts do not speak for themselves, nor do figures add up on

their own. Even the most vividly detailed printout requires someone to make sense

of the information it contains.‖

Statistics - these can provide excellent support. Be sure your statistics come

from responsible sources. Statistical evidence is the kind of data people tend to

look for first when trying to prove a point. That‘s not surprising when you

consider how prevalent it is in today‘s society. Remember those McDonald‘s

signs that said ―Over 1 billion served‖? How about those Trident chewing gum

commercials that say ―4 out of 5 dentists recommend chewing sugarless gum‖?

Every time you use numbers to support a main point, you‘re relying on statistical

evidence to carry your argument. [8, pp.83-95]

Quotes - direct quotes from leading experts that support your position are

invaluable.

Examples - Examples enhance your meaning and make your ideas concrete.

They are the proof. Sometimes making an argument can be strengthened by being

specific. If I tell you in class that not having insurance is a problem, this is a claim,

but does not have any evidence supporting it. I may then go on and describe that

people without insurance often delay going to the doctor, go to emergency rooms

for routine care instead of to clinics or doctors' offices, or go without care at all.

These last points are examples. The examples could further be strengthened by

statistics on how often uninsured people delay care, go to the emergency room, or

go without care. The information could be strengthened yet further by comparing

these statistics to similar statistics on people who have insurance. And so on.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-53-2048.jpg)

![55

you need is one example that contradicts a claim. Be careful when using this type

of evidence to try and support your claims. One example of a non-native English

speaker who has perfect grammar does NOT prove that ALL non-native English

speakers have perfect grammar. All the anecdote can do is disprove the claim that

all immigrants who are non-native English speakers have terrible grammar.

You CAN use this type of evidence to support claims, though, if you use it

in conjunction with other types of evidence. Personal observations can serve as

wonderful examples to introduce a topic and build it up – just make sure you

include statistical evidence so the reader of your paper doesn‘t question whether

your examples are just isolated incidents. There are appropriate ways to use this

type of evidence. It may focus an argument, provide an example, or illuminate. It

may make the reading more interesting. Just don't rely on this type of information

only. [66]

Analogy - is mainly useful when dealing with a topic that is under-

researched. If you are on the cutting edge of an issue, you‘re the person breaking

new ground. When you don‘t have statistics to refer to or other authorities on the

matter to quote, you have to get your evidence from somewhere. Analogical

evidence steps in to save the day. Take the following example: You work for a

company that is considering turning some land into a theme park. On that land

there happens to be a river that your bosses think would make a great white-water

rafting ride. They‘ve called on you to assess whether or not that ride would be a

good idea. Since the land in question is as yet undeveloped, you have no casualty

reports or statistics to refer to. In this case, you can look to other rivers with the

same general shape to them, altitude, etc. and see if any white-water rafting

casualties have occurred on those rivers. Although the rivers are different, the

similarities between them should be strong enough to give credibility to your

research. Realtors use the same type of analogical evidence when determining the

value of a home.

Analogy may be a writing tool to make your points clear and interesting, but](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-55-2048.jpg)

![56

you may also use analogies as evidence. For instance, if you are studying a

relatively new government policy or a new trend in health care markets, you may

need to speculate on the benefits/costs of the policy based on results from similar

policies that have been instituted in the past or in trends from other markets that are

similar. You will need to use reasoning and logic to make the connections. You

should also describe the possible differences between past policies and today or

non-health markets and healthcare markets, etc... and how these differences might

affect your conclusions, but this type of evidence can be very persuasive.

When you use analogies to support your claims, always remember

their power. [67]

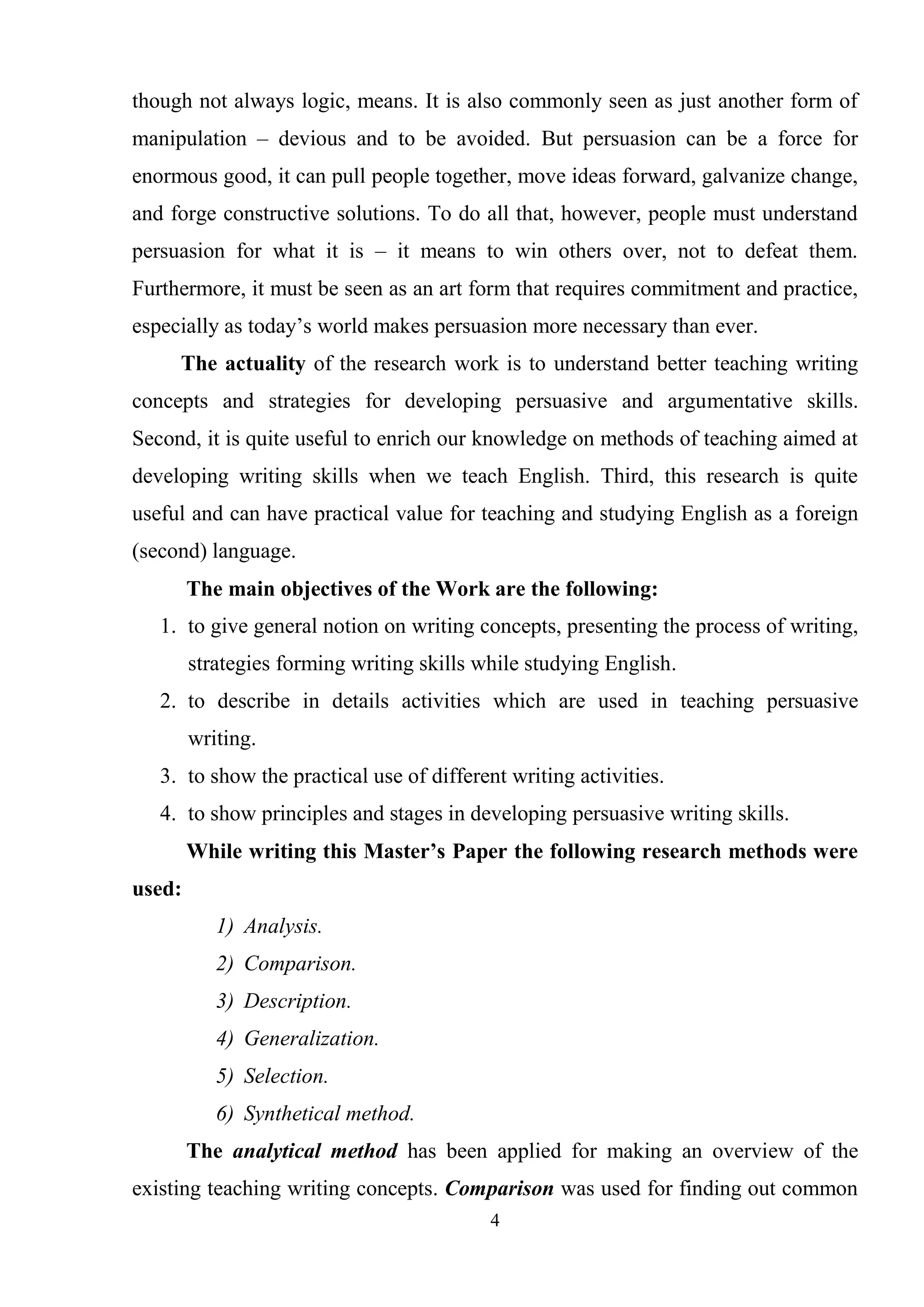

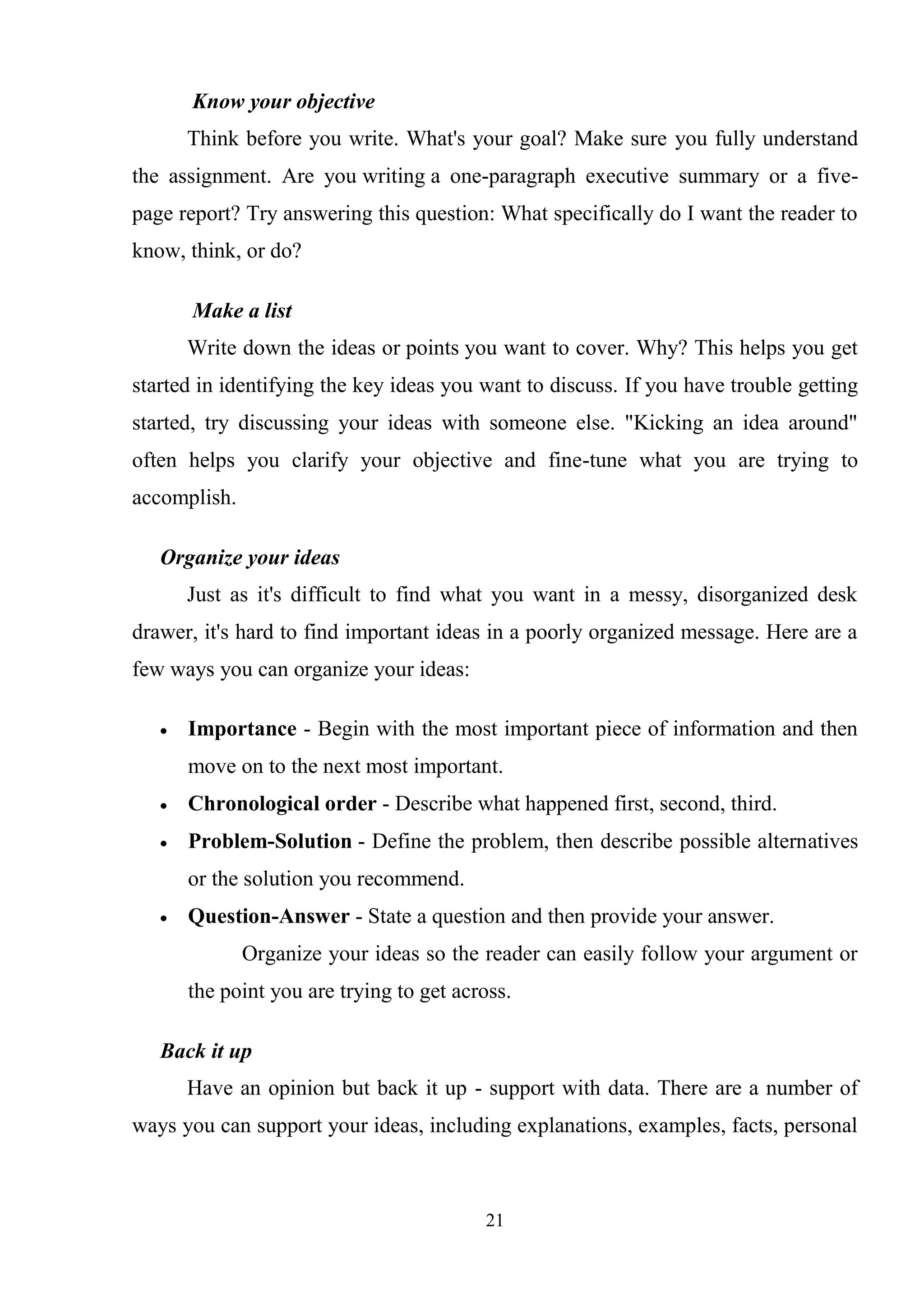

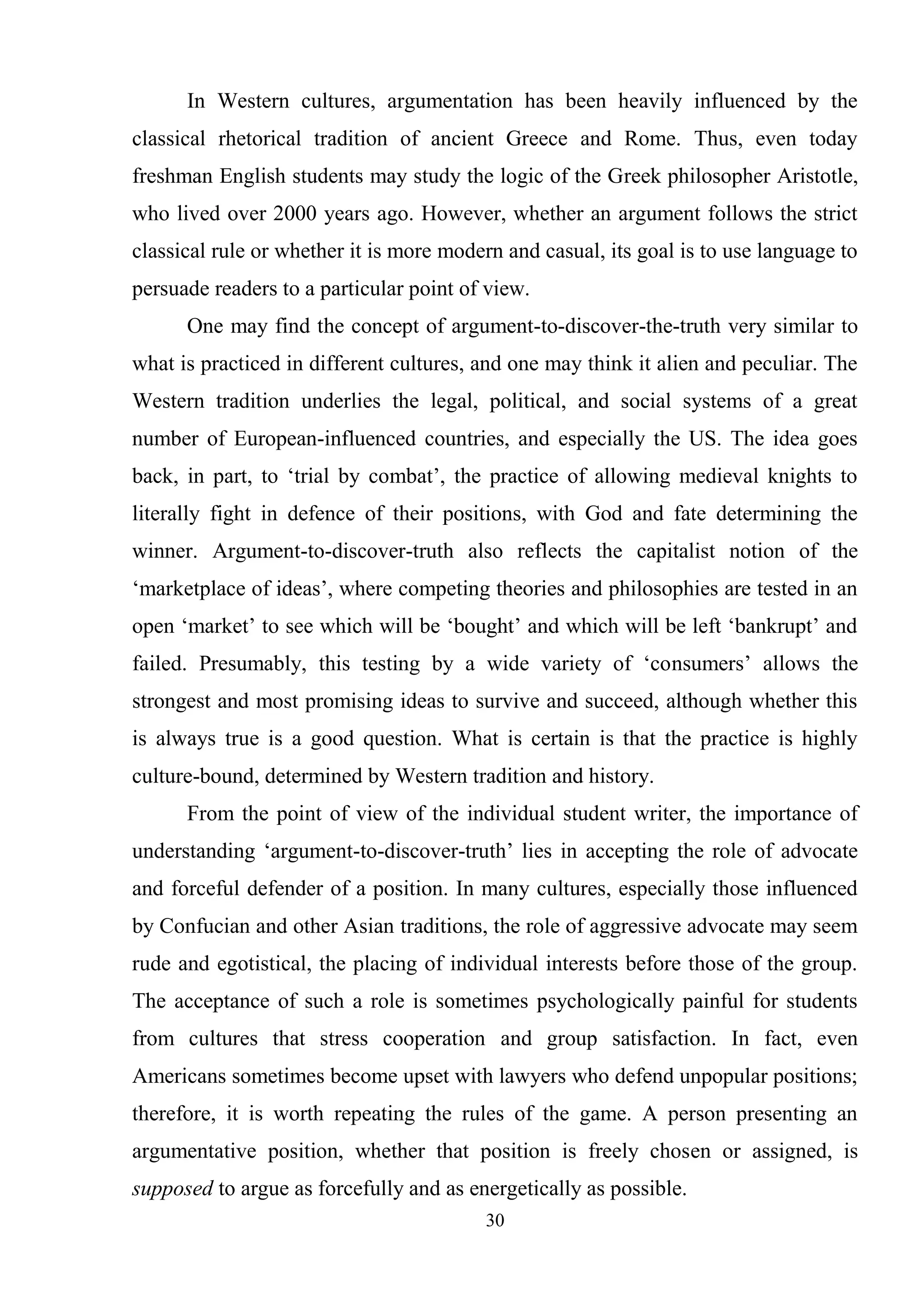

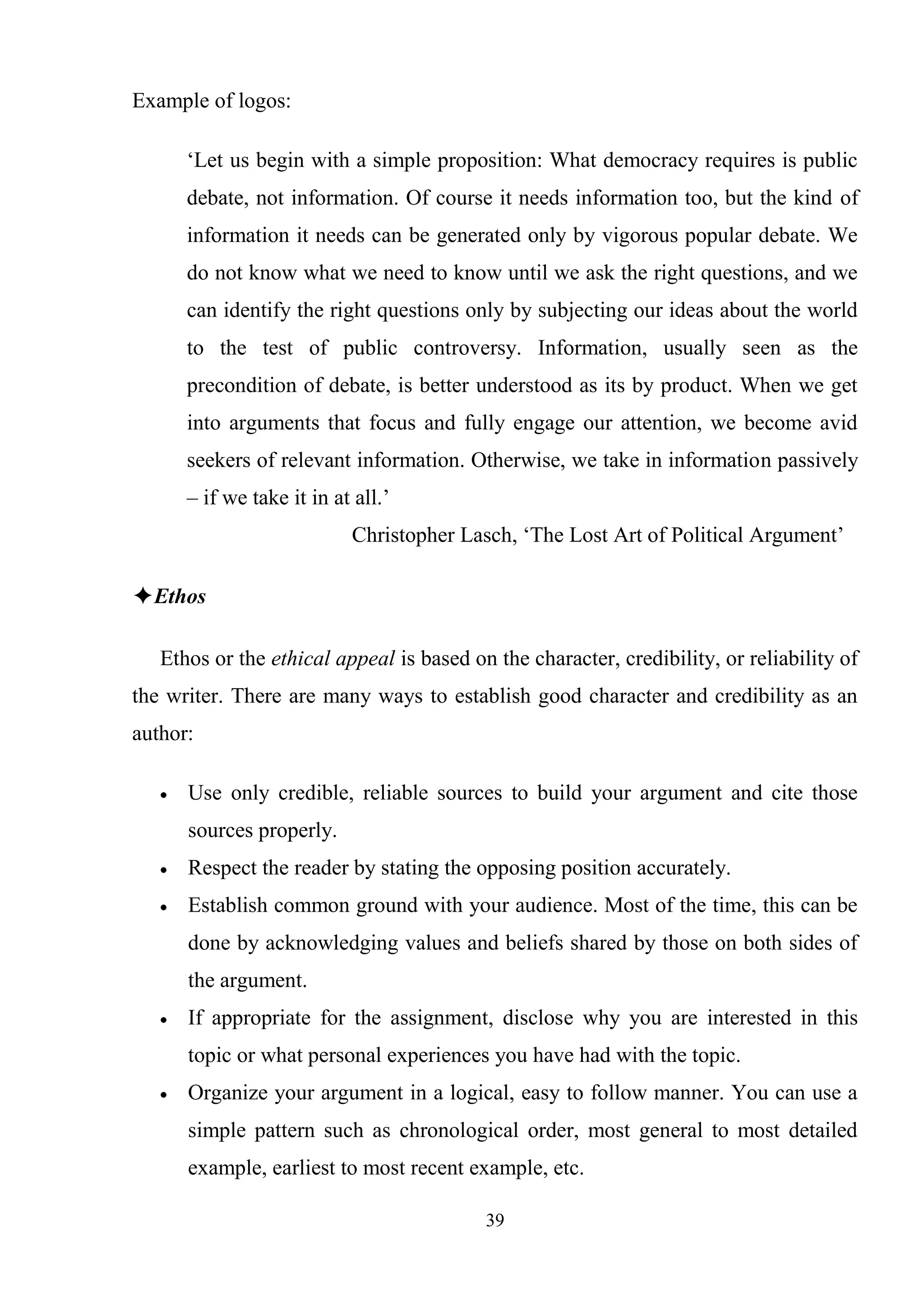

Evidence provides support for claims. Evidence is subcategorized according

to how it is used to support the claim. Evidence that focuses on our ability to think

is classified as rational appeal, evidence that focuses on our ability to 'feel'

is emotional appeal, and evidence that focuses on our ability to trust those we find

to be credible is ethical appeal.

TYPES OF EVIDENCE

[63]

Rational Appeals

Facts

Case studies

Statistics

Experiments

Logical reasoning

Analogies

Anecdotes

Emotional Appeals

Higher emotions

- Altruism

- Love …

Base emotions

- Greed

- Lust

Ethical Appeals

Trustworthiness

Credibility:

-expert testimony

-reliable sources

Fairness](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-56-2048.jpg)

![57

At least in theory, arguments should avoid the personal and the emotional. An

argument may try to move the feelings of its listeners or hearers – pictures of

burned forests to persuade campers to be careful about smoking and putting out

campfires would be an example – but it should use evidence to do so. The evidence

could be of many kinds: statistics, examples, illustrations, the testimony of experts,

the results of experiments, quotes from documents, and so on. The nature of the

evidence used in arguments is probably less important than its sources, which are

supposed to be objective and fair, and its appropriateness to the subject. For

example, U.S. supermarkets sell many tabloid newspapers filled with fantastic

stories and revelations: Men from Mars have a cure for cancer might be a typical

headline. However, few people take this ‗news‘ seriously because the tabloid

newspapers themselves have little credibility, and the evidence used to back up

their claims is inadequate or nonexistent. One of the most important ways we

evaluate the truth of a statement is by considering its source.

Arguments need not be based on factual evidence; they may instead use a

series of generally accepted statements to move the reader toward a conclusion.

For example, to convince students that the tuition they pay for class should be

raised, a college might compile statistics about rising costs and examples of

comparable costs at other institutions; or the argument could consist of a series of

assertions which students might be likely to accept as true: This college has always

charged the minimum possible for its classes; the college‘s costs go up at the same

rate as everyone else‘s; we will have to raise tuition. [48, pp.142-151]

Solid evidence is:

Relevant: speaks directly to the point.

Representative: you cannot make a point for the whole U.S. population

based on information about one state, for example. If information is only

available for one state, present the evidence, but note the problems.

Accurate: try to find the same information in more than one place, if

possible.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-57-2048.jpg)

![58

Detailed: provide as much as possible. If you know how many thousands of

people smoke, tell us the exact number, don't just say "thousands smoke."

Adequate: Figure out which are the most important points in your arguments

and support these in the most detail. Lesser points also need evidence, but

don't get bogged down on debating a minor detail of the policy.

Using Evidence

Distinguish facts from informed opinion or speculation.

Use statistics carefully.

Use examples to clarify meaning, demonstrate why, or to entertain.

Use logic and reason to connect the evidence to the points.

Use personal experience or anecdotal evidence sparingly. [67]

Credibility

The credibility of an argument means whether or not others believe it is true.

Credibility is obviously an important value in everyday life as well as in writing,

and it is worth considering what makes us believe or disbelieve the statements of

our friends, of salespeople, of teachers, and other authority figures. Obviously,

some people evoke more trust than others, but that is a circular argument, for it

suggests that some people have credibility because they create trust and that we

trust some people because they have credibility. It is more helpful to ask what

causes these trusting feelings in the first place.

Belief is usually created when what people claim to be is true is confirmed

later on, when it is verified by later events or by other people. These verifications

by other people also affect our initial belief; we tend to go along with the majority,

placing a great deal of trust in respected sources such as The New York Times or a

university or government agency and very little in the supermarket tabloids

mentioned above. This is because it is impossible for average individuals to verify

facts themselves; we must trust authorities for most of our information, and we

learn which authorities have credibility from the opinions of other people. For](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-58-2048.jpg)

![59

instance, consider an example like, ‗There are over four billion people in the world

today.‘ This statement is impossible to verify directly: no one could count the

world‘s population alone. Yet it is clearly ‗factual‘ since the various agencies

which keep track of such figures, such as the United Nations, confirm this figure. It

would also be possible to decide that some sources – say a poetry journal or a

sports magazine – might not have much credibility in estimating the world‘s

population, were they do so, although, of course, they might have great credibility

in their own field. Thus, careful writers are also careful readers of sources of

information and ask themselves whether their sources are considered credible by

others, whether these ‚others‘ themselves are credible, and whether the sources are

operating within their fields of expertise. [46, pp.186-204]

2.4 Argumentation

While some teachers consider persuasive papers and argument papers to be

basically the same thing, it‘s usually safe to assume that an argument paper

presents a stronger claim—possibly to a more resistant audience. For example:

while a persuasive paper might claim that cities need to adopt recycling programs,

an argument paper on the same topic might be addressed to a particular town. The

argument paper would go further, suggesting specific ways that a recycling

program should be adopted and utilized in that particular area. To write an

argument paper or essay, you’ll need to gather evidence and present a well-

reasoned argument on a debatable issue. [71]

The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 3rd

Edition gives

the following definition to ‗argument‘:

putting forth reasons for or against; debating;

attempting to prove by reasoning; maintain or content;

giving evidence of; indicate;

persuading or influence (another), as by presenting reasons.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-59-2048.jpg)

![60

The argumentative writing requires that the student will investigate a topic,

collect, generate, and evaluate evidence, and establish a position on the topic in a

concise manner. The argumentative essay is commonly assigned as a capstone or

final project in first year writing or advanced composition courses and involves

lengthy, detailed research. Argumentative essay assignments generally call for

extensive research of literature or previously published material. Argumentative

assignments may also require empirical research where the student collects data

through interviews, surveys, observations, or experiments. Detailed research

allows the student to learn about the topic and to understand different points of

view regarding the topic so that s/he may choose a position and support it with the

evidence collected during research. Regardless of the amount or type of research

involved, argumentative essays must establish a clear thesis and follow sound

reasoning. [51, pp.287-320]

The word "argument" does not have to be written anywhere in the assignment

for it to be an important part of the task. In fact, making an argument—expressing

a point of view on a subject and supporting it with evidence—is often the aim of

academic writing. Many instructors may assume that students know this and thus

may not explain the importance of arguments in class.

Most material one learns in college or university is or has been debated by

someone, somewhere, at some time. Even when the material you read or hear is

presented as simple "fact," it may actually be one person's interpretation of a set of

information. Instructors may call on you to examine that interpretation and defend

it, refute it, or offer some new view of your own. In writing assignments, you will

almost always need to do more than just summarize information that you have

gathered or regurgitate facts that have been discussed in class. You will need to

develop a point of view on or interpretation of that material and provide evidence

for your position. [76]

One may think that "fact," not argument, rules intelligent thinking, below is an

example for consideration. For nearly 2000 years, educated people in many](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-60-2048.jpg)

![64

Narrowed debatable thesis 2:

America's anti-pollution efforts should focus on privately owned cars

because it would allow most citizens to contribute to national efforts and

care about the outcome.

This thesis narrows the scope of the argument by specifying not just what the focus

of a national anti-pollution campaign should be but also why this is the appropriate

focus.

Qualifiers such as "typically," "generally," "usually," or "on average" also help to

limit the scope of your claim by allowing for the almost inevitable exception to the

rule. [73]

Types of Thesis Statements/ Claims

Claims typically fall into one of four categories. Thinking about how you want to

approach your topic, in other words what type of claim you want to make, is one

way to focus your thesis on one particular aspect of you broader topic.

Claims of fact or definition: These claims argue about what the definition of

something is or whether something is a settled fact. Example:

What some people refer to as global warming is actually nothing more than

normal, long-term cycles of climate change.

Claims of cause and effect: These claims argue that one person, thing, or event

caused another thing or event to occur. Example:

The popularity of SUV's in America has caused pollution to increase.

Claims about value: These are claims made about what something is worth,

whether we value it or not, how we would rate or categorize something. Example:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-64-2048.jpg)

![66

How recent is the source? The choice to seek recent sources depends on

your topic. While sources on the American Civil War may be decades old and still

contain accurate information, sources on information technologies, or other areas

that are experiencing rapid changes, need to be much more current.

What is the author's purpose? When deciding which sources to use, you

should take the purpose or point of view of the author into consideration. Is the

author presenting a neutral, objective view of a topic? Or is the author advocating

one specific view of a topic? Who is funding the research or writing of this source?

A source written from a particular point of view may be credible; however, you

need to be careful that your sources don't limit your coverage of a topic to one side

of a debate.

What type of sources does your audience value? If you are writing for a

professional or academic audience, they may value peer-reviewed journals as the

most credible sources of information. If you are writing for a group of residents in

your hometown, they might be more comfortable with mainstream sources, such

as Time or Newsweek. A younger audience may be more accepting of information

found on the Internet than an older audience might be.

Be especially careful when evaluating Internet sources! Never use Web

sites where an author cannot be determined, unless the site is associated with a

reputable institution such as a respected university, a credible media outlet,

government program or department, or well-known non-governmental

organizations. Beware of using sites like Wikipedia, which are collaboratively

developed by users. Because anyone can add or change content, the validity of

information on such sites may not meet the standards for academic research.

[4, pp.58-72]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-66-2048.jpg)

![71

A conclusion that does not simply restate the thesis, but readdresses it in

light of the evidence provided.

It is at this point of the essay that students may begin to struggle. This is the

portion of the essay that will leave the most immediate impression on the mind of

the reader. Therefore, it must be effective and logical. Do not introduce any new

information into the conclusion; rather, synthesize the information presented in the

body of the essay. Restate why the topic is important, review the main points, and

review your thesis. You may also want to include a short discussion of more

research that should be completed in light of your work. [9, pp.138-144]

2.5 Persuading Effectively

―They who influence the thoughts of their times, influence all the times that

follow. They have made their impression on eternity.‖ Anonymous

Persuasion requires technique. No one would believe anything said by

another until and unless he or she is persuaded into believing it. Whether you are

writing an advertisement, an email to a friend or an essay trying to convince a

group of people to come over to your way of thinking, you need to know the

methods top persuaders use to change people‘s thinking and get them to take

action. Persuasion can be done by certain methods.

Here is a collection of the most persuasive techniques used by politicians,

advertising copywriters, spin-doctors, propaganda writers, lawyers etc., anybody

who has to change an individual‘s mind–or groups of people‘s minds–quickly.

A student could use these techniques to get people to do things they

wouldn‘t ordinarily do, change their beliefs, get them to change their minds, get

them to take action.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persuasionandargumentinwriting-130505111958-phpapp02/75/Persuasion-and-argument-in-writing-71-2048.jpg)

![81

• Do you know of any other baby food that makes your child healthier than Special

Baby Food? (NOTE: Whether they answer yes or no, by answering the question

they imply that Special Baby Food will make their child healthy.)

When writing, ask yourself how you are going to imply your claims.

■ Use Rhetorical Questions to Make Claims

This one is used a lot by the mass media, because it lets claims slip into

readers‘ minds without resistance. If I say, ―XYZ tablets let you lose weight while

you sleep,‖ you probably won‘t really believe it; you‘ve heard claims like this all

the time. But if I ask, ―How has XYZ tablets helped thousands of people across the

USA lose weight while they sleep?―, it has a better chance of being accepted

without resistance.

Take a claim that you want to make, and try out different types of questions

to frame it in.

Example: How do Decatrim pills help you boost your self-confidence?

When you are writing, ask yourself, ―How can I put some of my claims into

question form?‖

When working on your project, keep sentences fairly short. One mistake in

ads and other forms of persuasive writing is sentences that are too long. The longer

your sentences, the more difficult they are too read, and the more likely they will

be ignored. You can mix and match these techniques depending on your project.