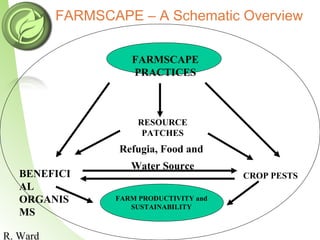

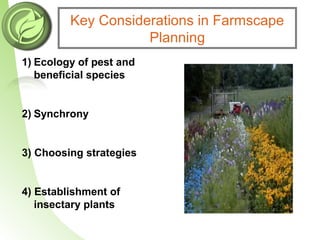

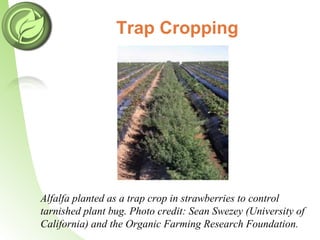

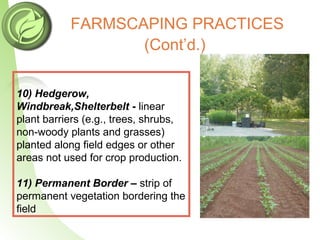

Farmscaping is a whole-farm approach to pest management through biodiversity. It involves establishing hedgerows, insectary plants, cover crops, and water reservoirs to attract beneficial organisms like parasitic insects and birds. This increases biodiversity and biological control of pests, while improving farm productivity and sustainability. The document outlines various farmscaping practices like companion planting, trap cropping, and hedgerows. It discusses selecting plants that provide food and habitat for beneficial insects. Implementing farmscaping can reduce pesticide use, save money, and create a safer farm environment.