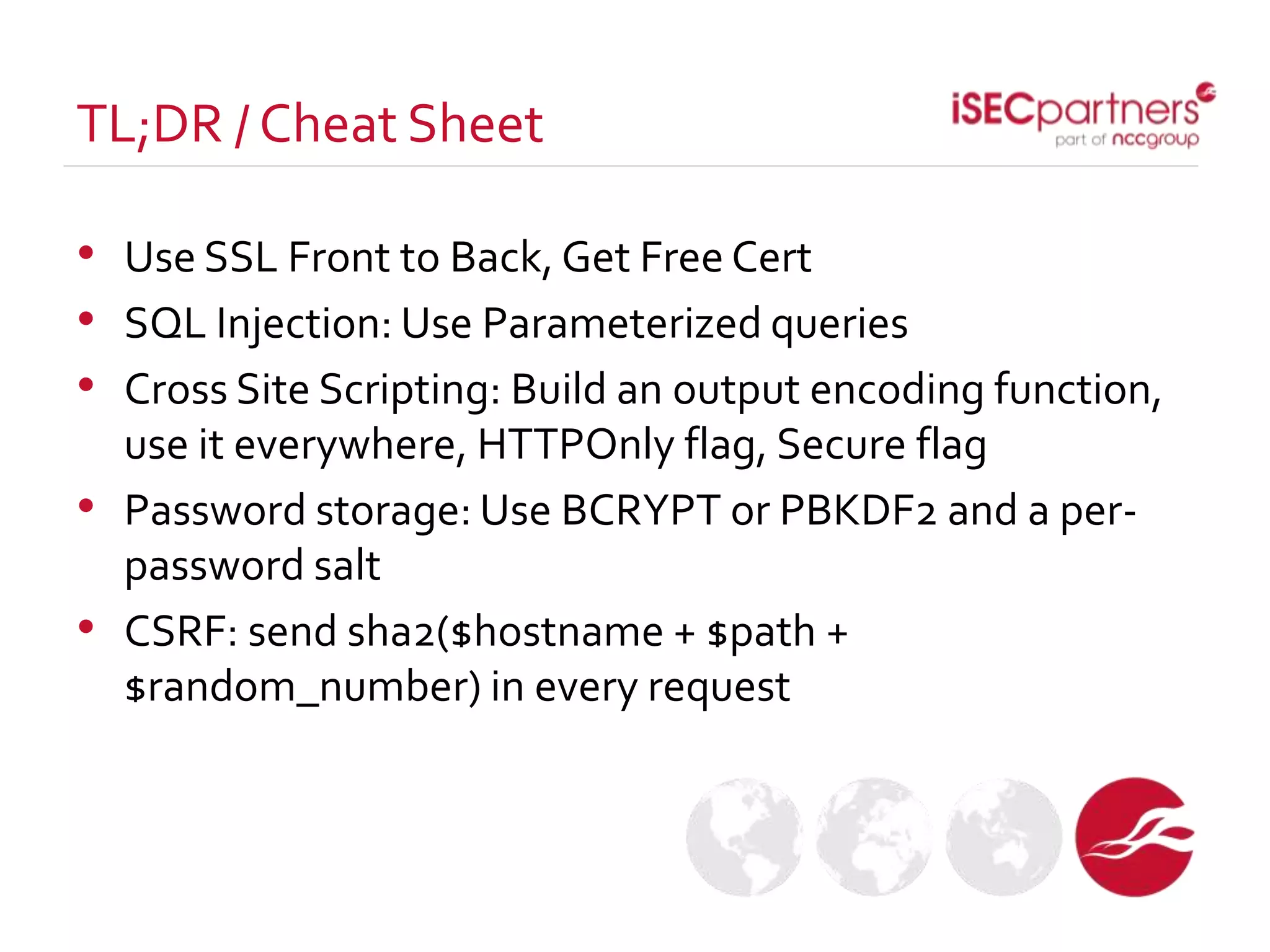

The document discusses how open source projects with limited resources can implement effective security measures. It recommends using SSL for all site traffic, parameterized queries to prevent SQL injection, encoding user input to prevent XSS, bcrypt or PBKDF2 with salts for secure password storage, and CSRF tokens for protection against cross-site request forgery. The key point is that planning for security early and implementing these strategies from the start is much more efficient than trying to retrofit protections later.