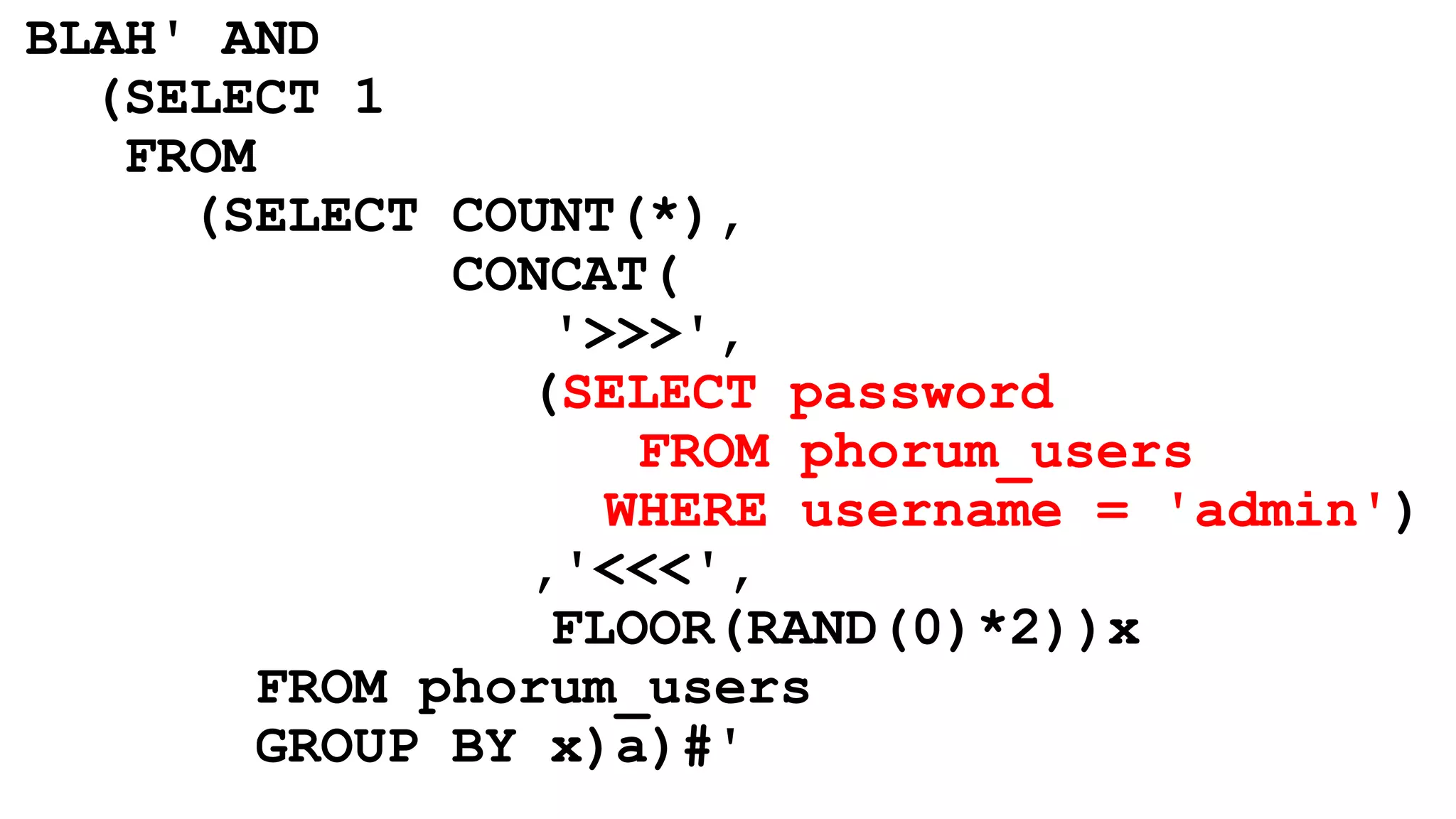

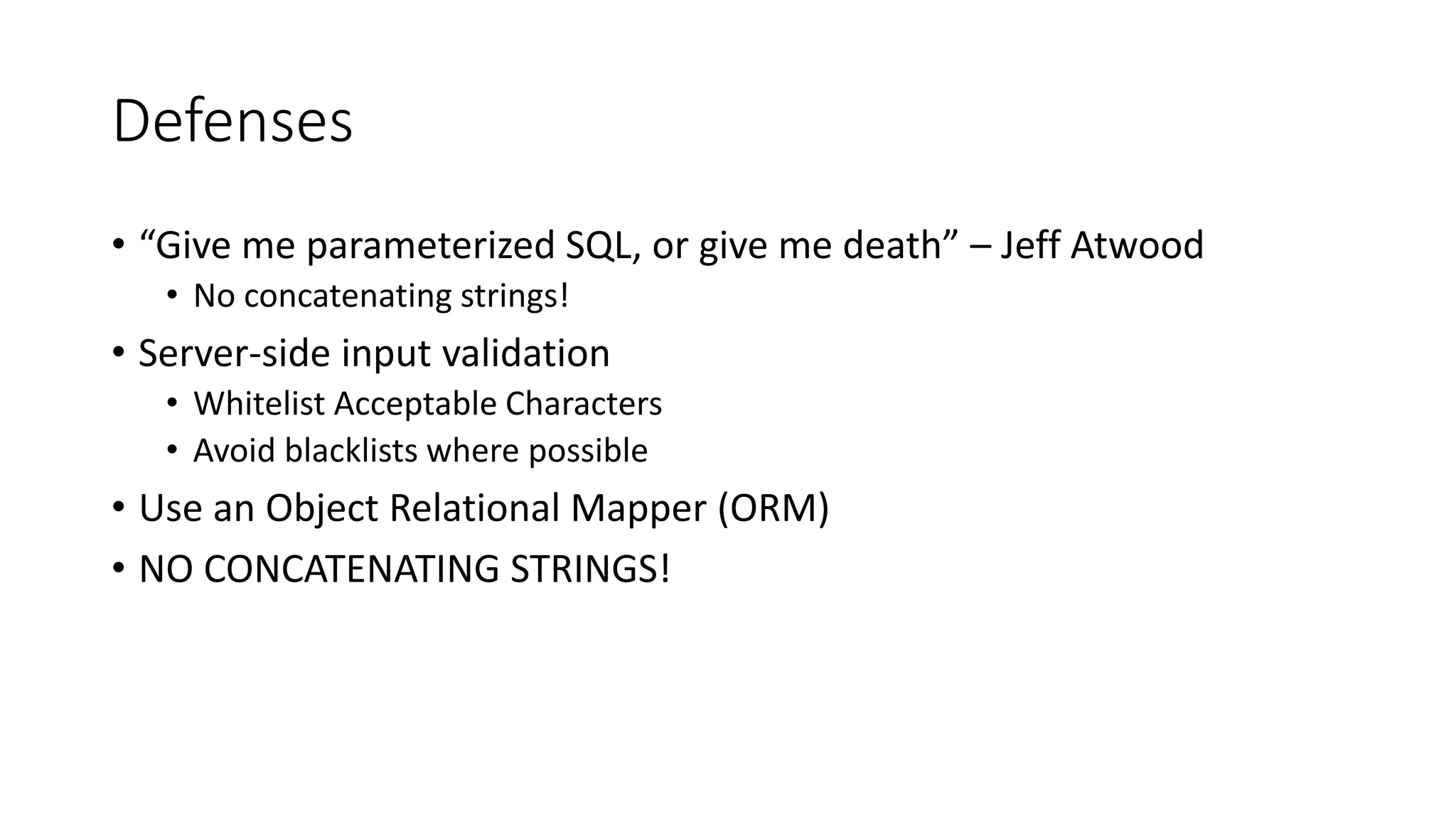

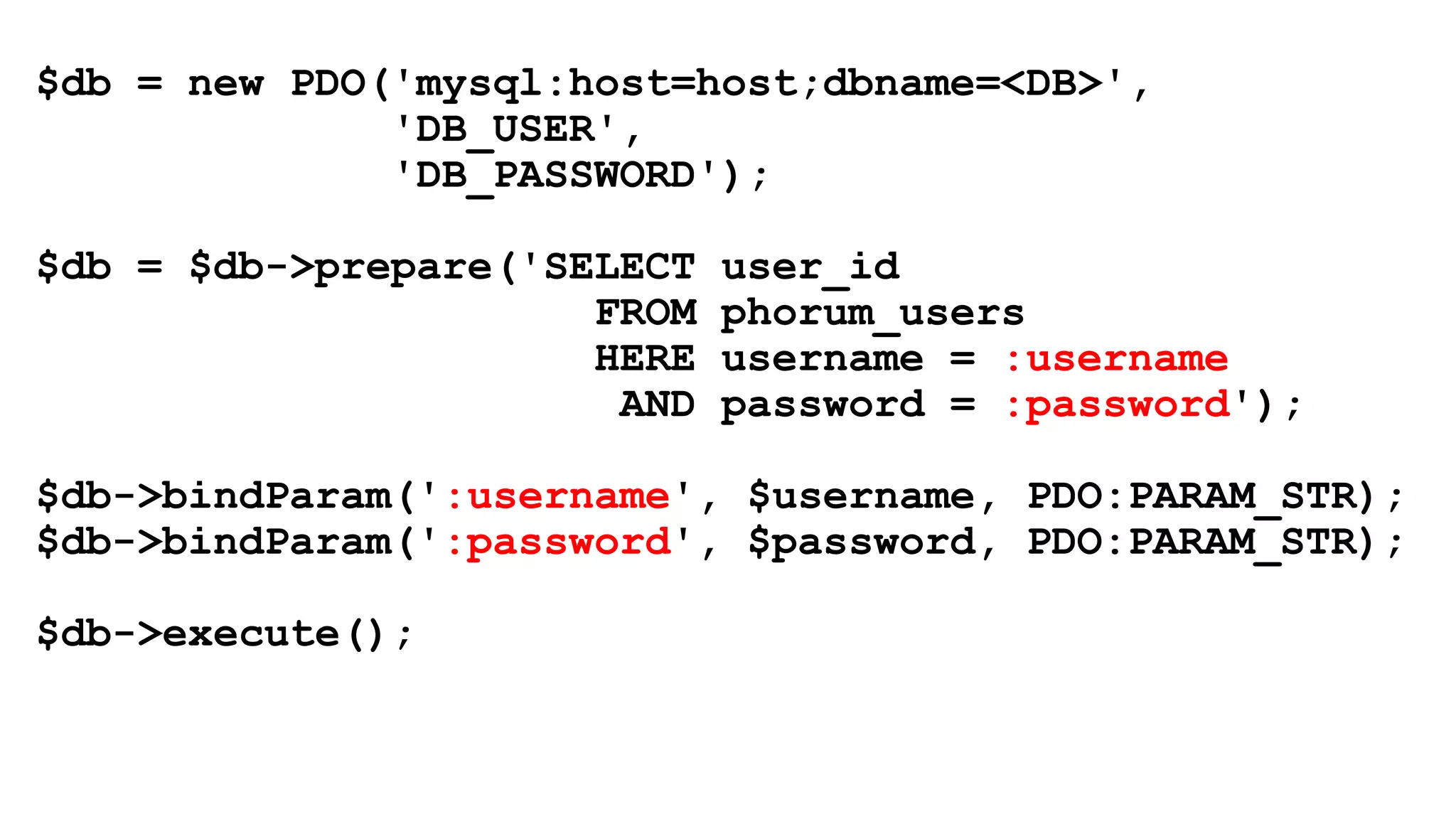

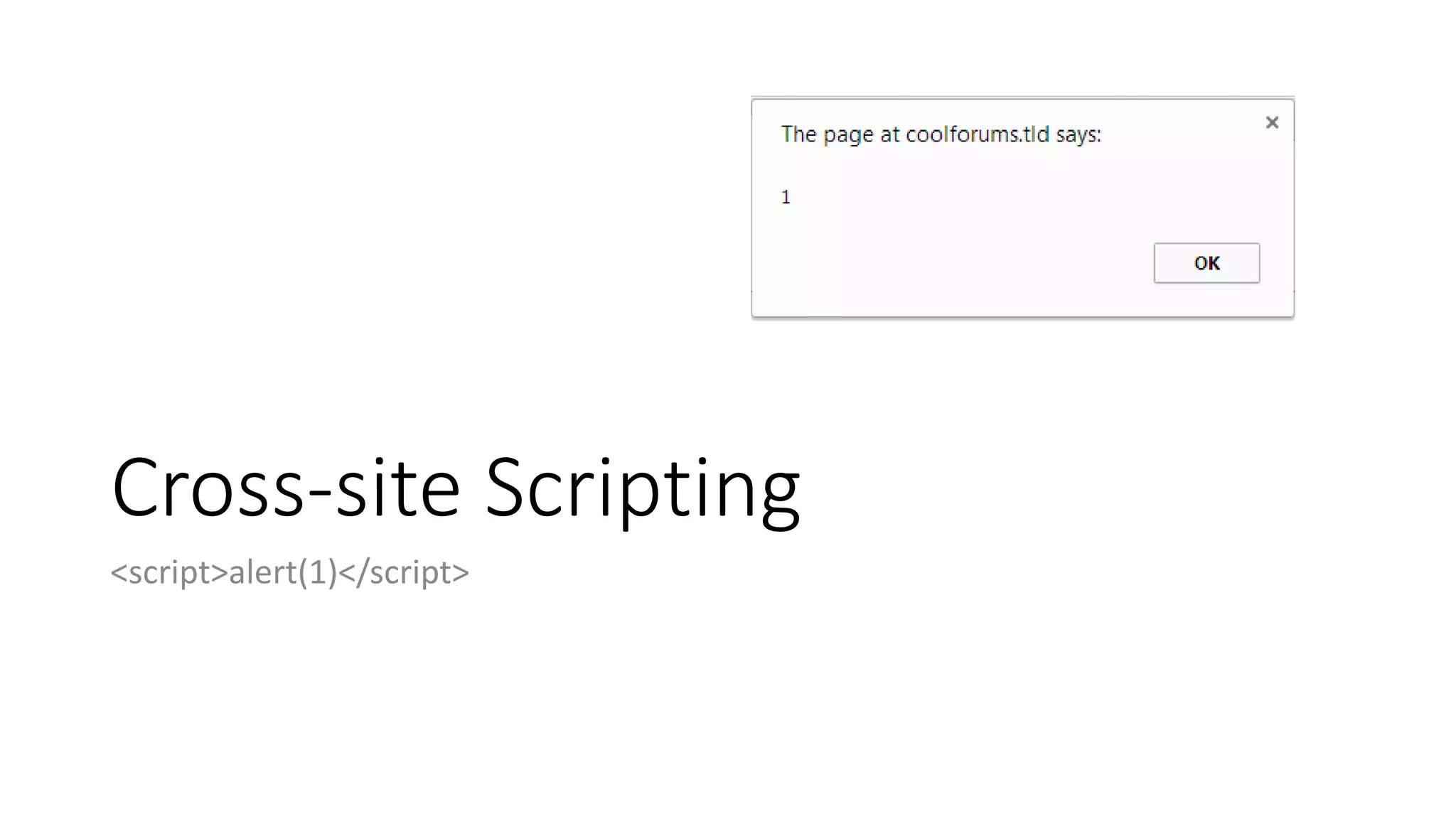

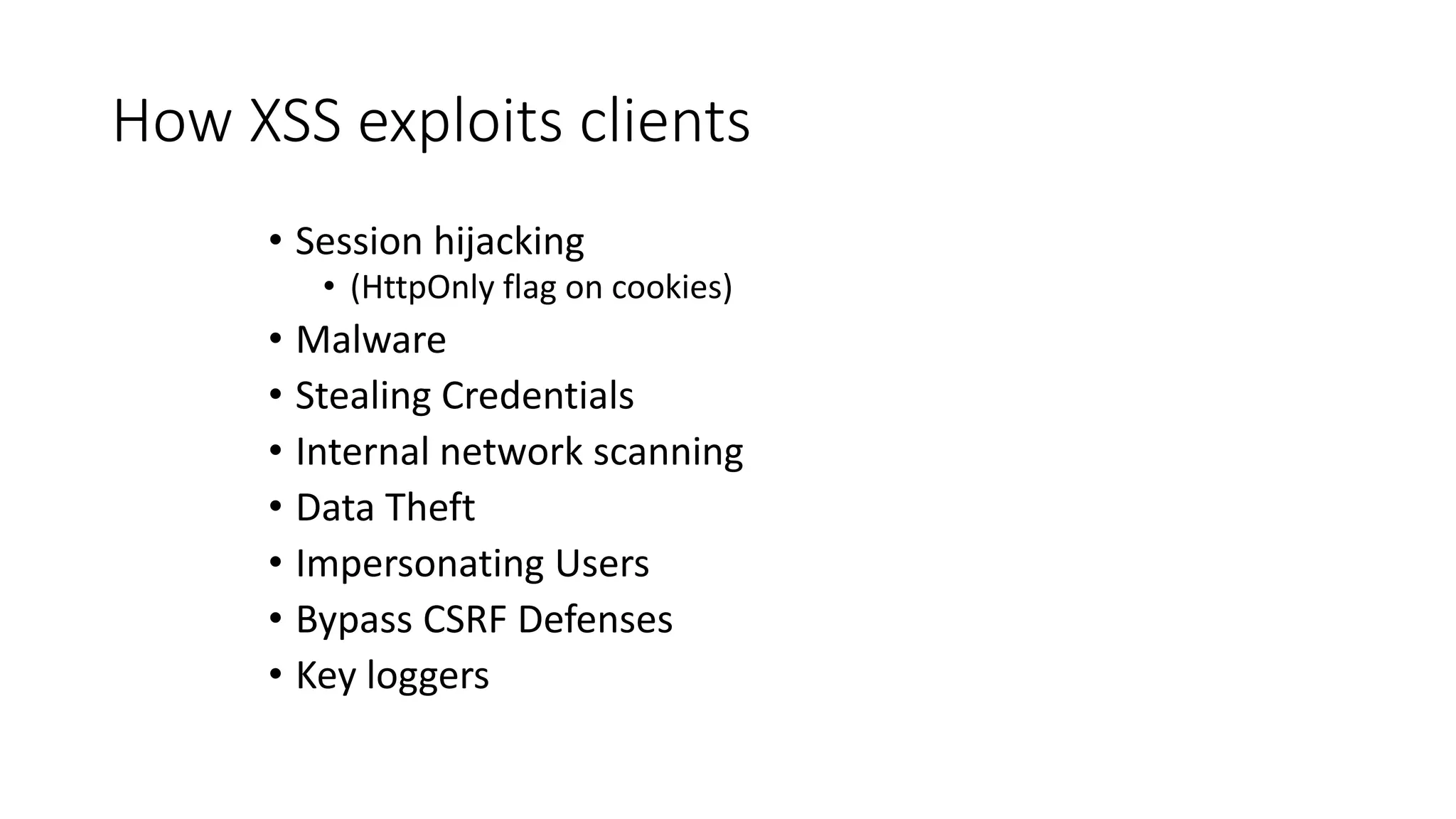

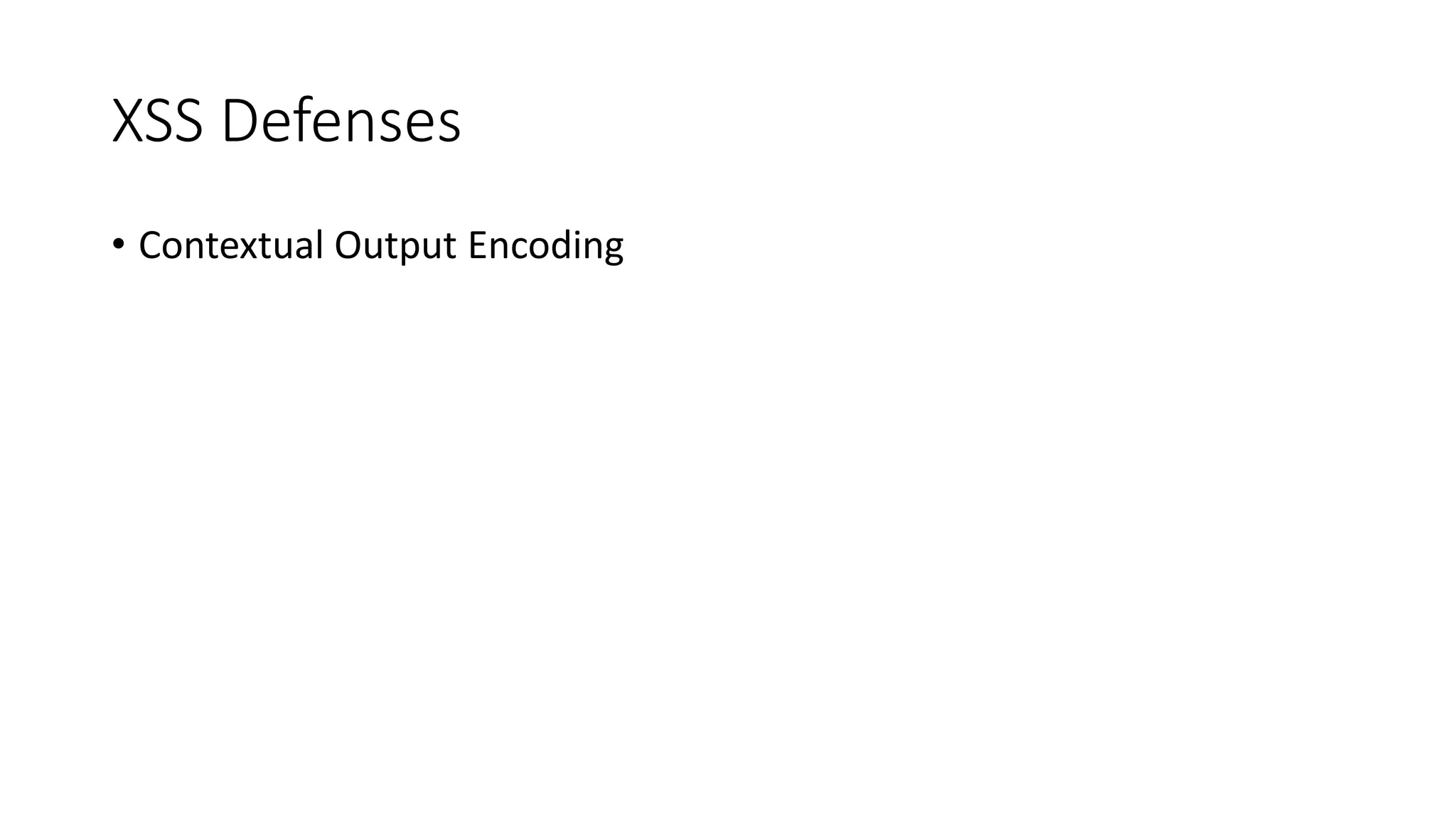

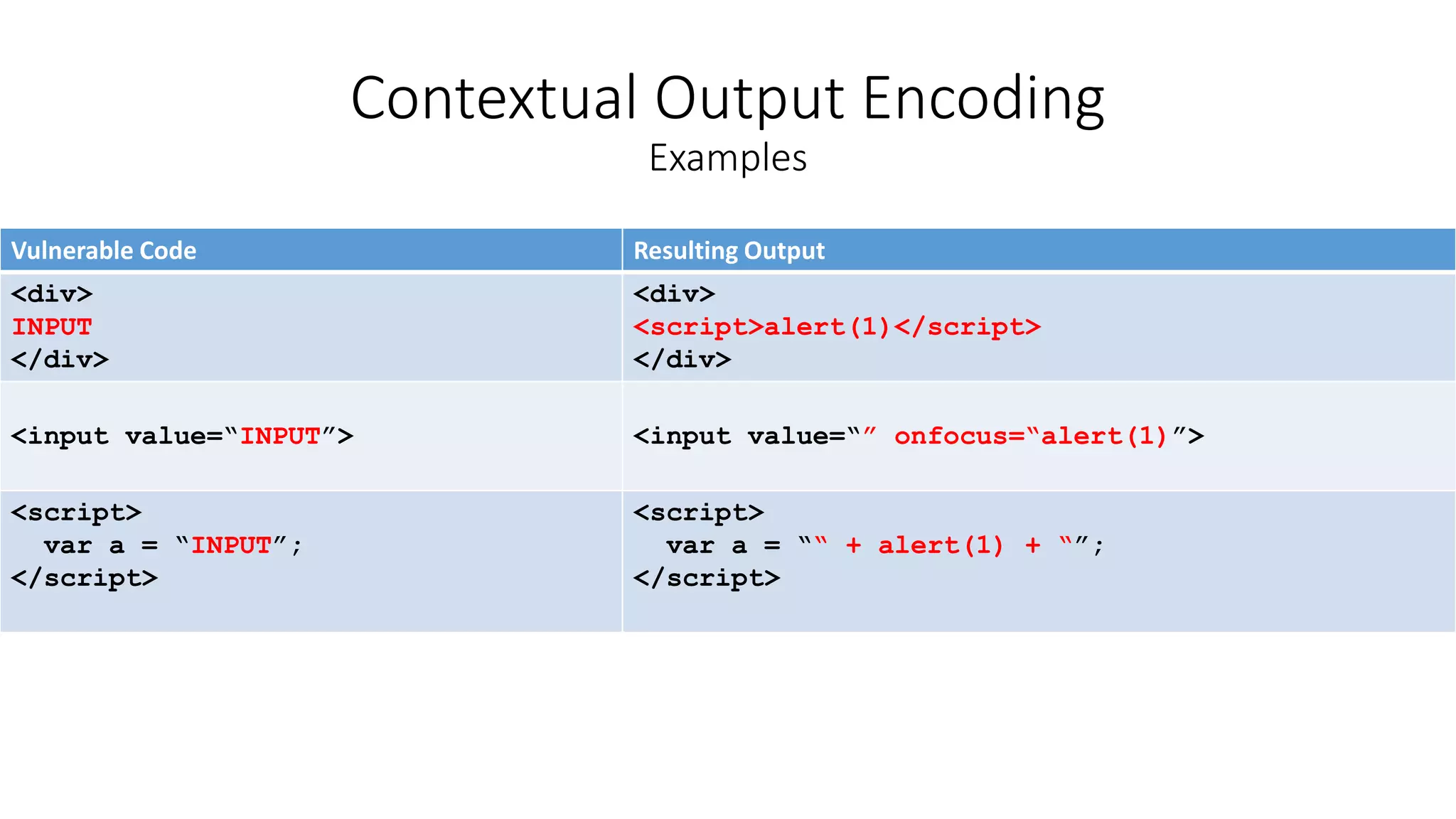

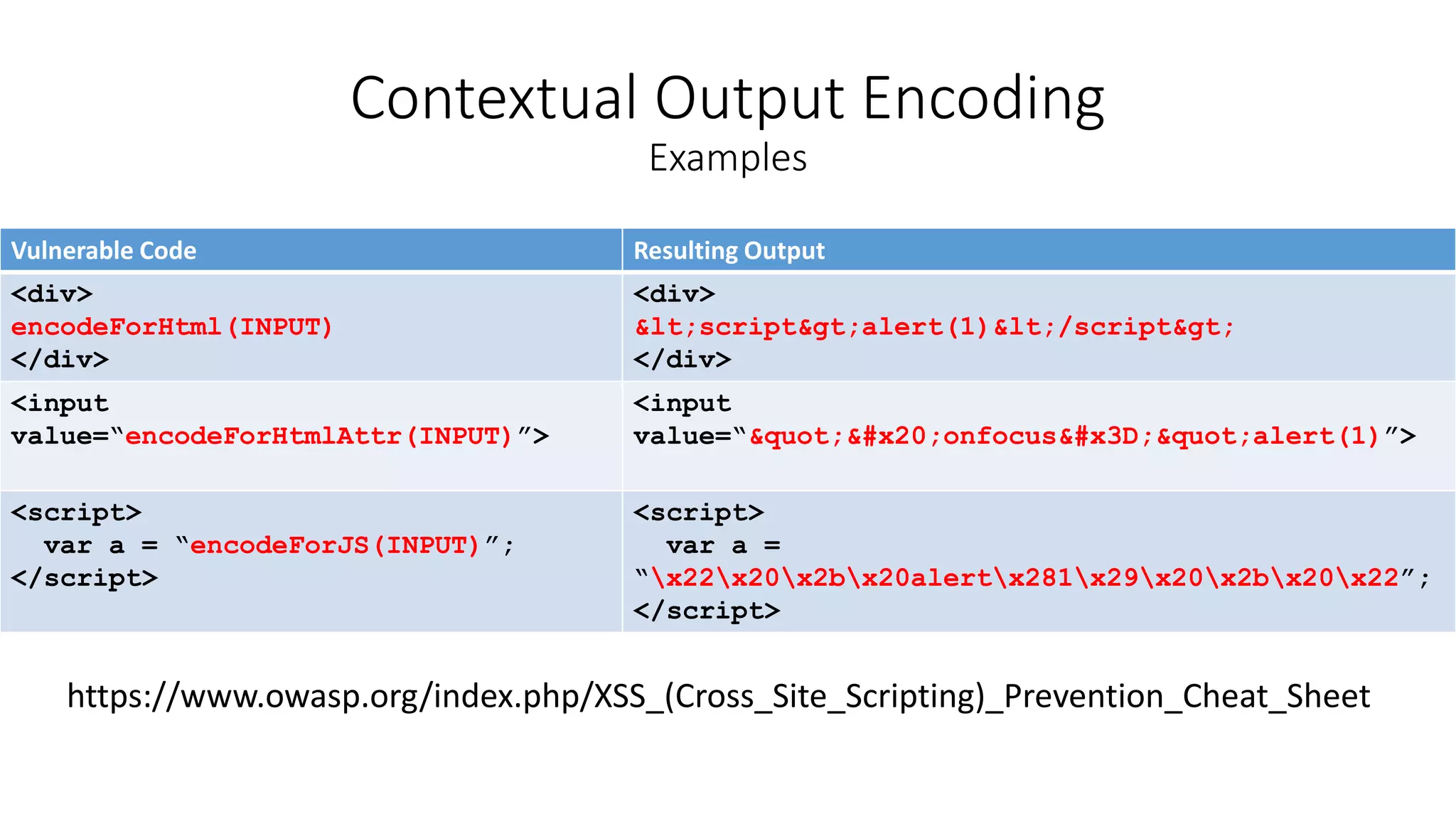

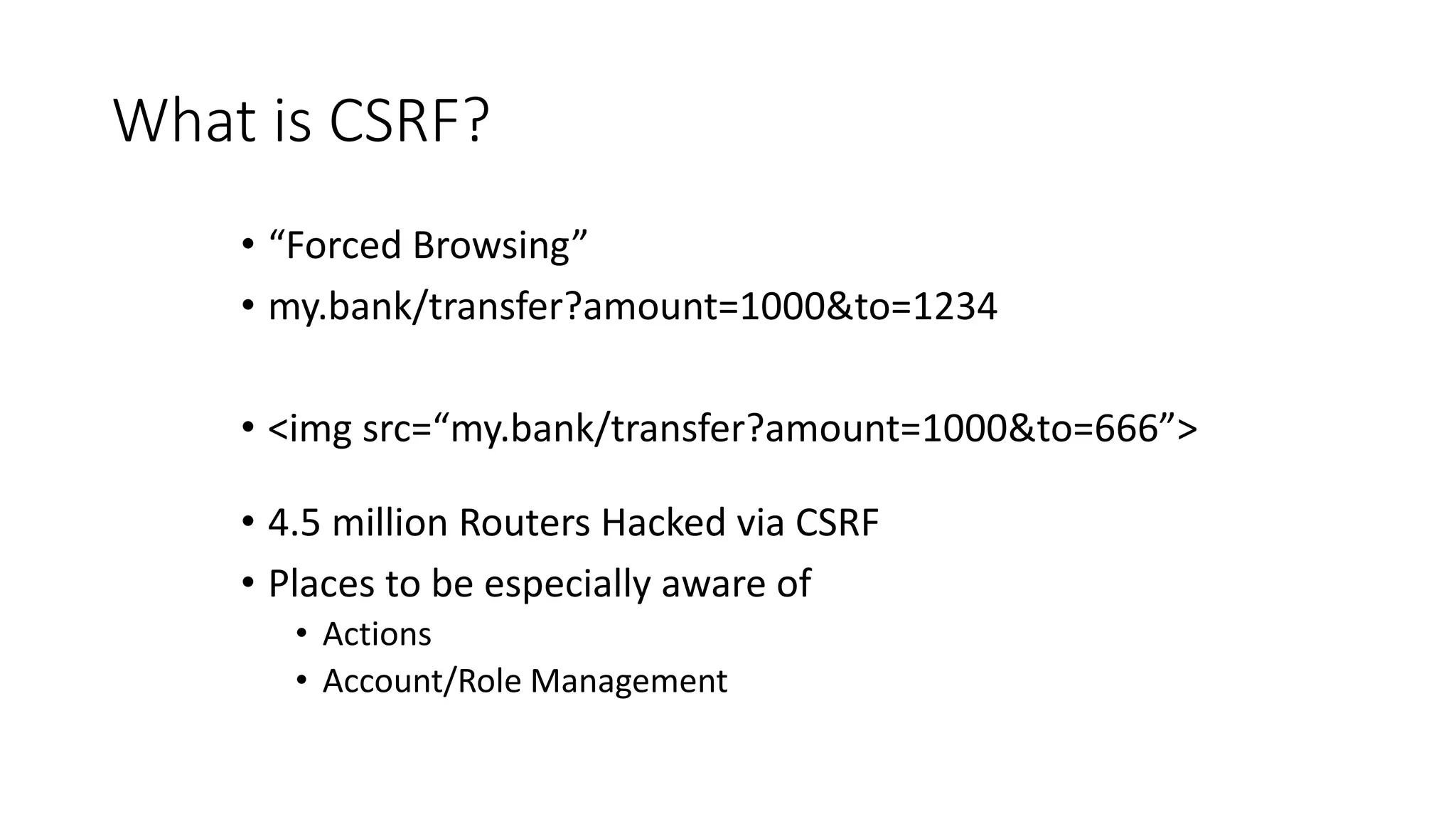

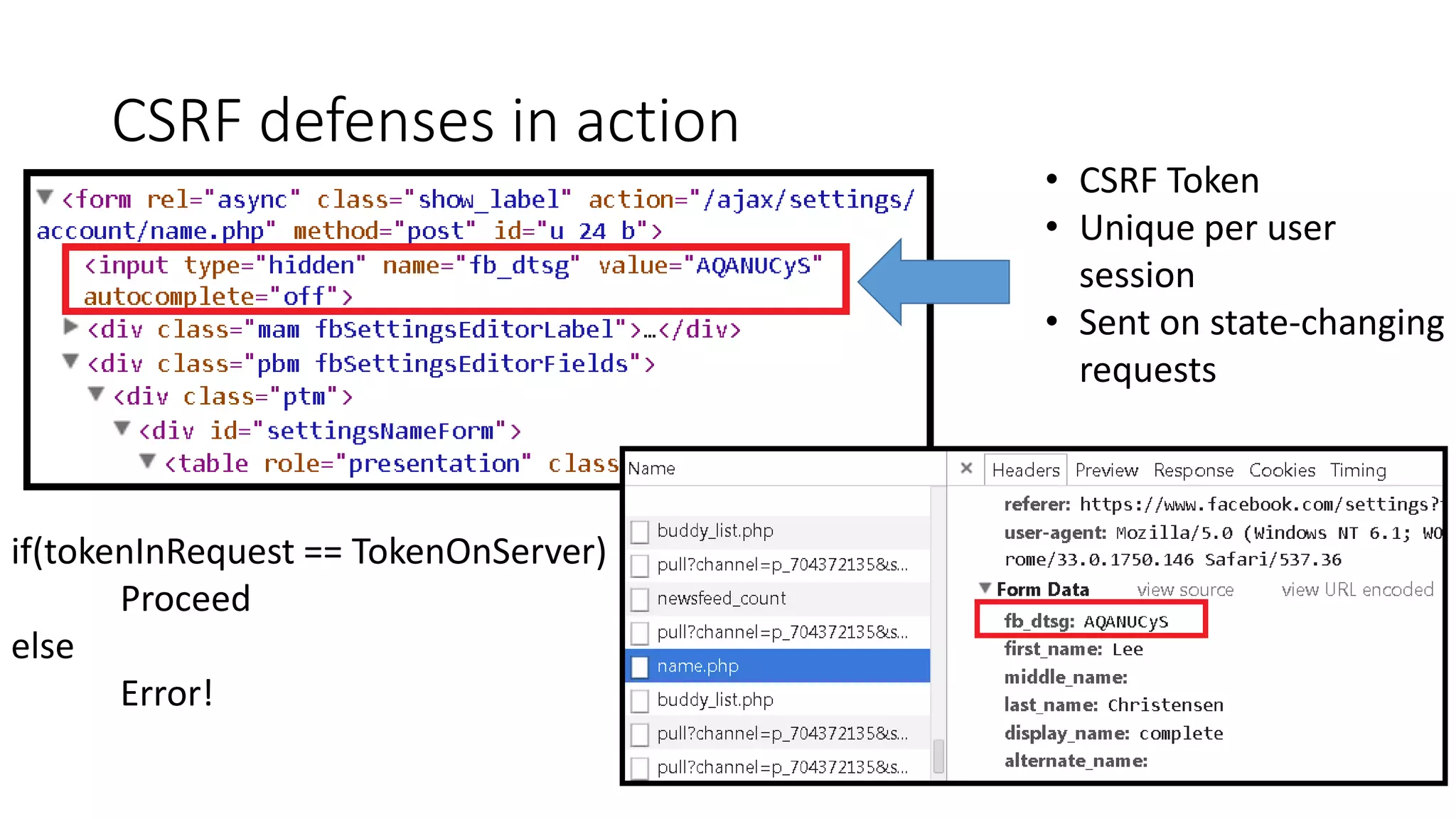

This document provides a summary of a presentation on web application security. It introduces the presenter and outlines topics that will be covered, including injection attacks like SQL injection and cross-site scripting (XSS), cross-site request forgery (CSRF), password storage techniques, and defenses against these attacks. Examples of each attack type are demonstrated. Defenses like input validation, output encoding, anti-XSS libraries, synchronizer tokens for CSRF, and password hashing with salts are discussed. The importance of secure coding practices and continued learning are emphasized.

![Example: ASP.NET MVC

Controller

[ValidateAntiForgeryToken]

public ActionResult DoSomething()

{

// Do stuff

}

View

<div>

@using (Html.BeginForm())

{

@Html.AntiForgeryToken()

//Other form elements

}

</div>](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/webapplicationsecurity-170215130603/75/Web-application-Security-30-2048.jpg)

![2) Use a cryptographically strong

credential-specific salt

•protect( [salt] + [password] );

•Use a 32char or 64char salt (actual size

dependent on protection function);

•Do not depend on hiding, splitting, or otherwise

obscuring the salt

Password Storage in the Real World](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/webapplicationsecurity-170215130603/75/Web-application-Security-38-2048.jpg)

![Leverage Keyed Functions

3a) Impose difficult verification on [only]

the attacker (strong/fast)

•HMAC-SHA-256( [private key], [salt] + [password] )

•Protect this key as any private key using best

practices

•Store the key outside the credential store

•Build the password-to-hash conversion as a separate

web service (cryptographic isolation).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/webapplicationsecurity-170215130603/75/Web-application-Security-39-2048.jpg)

![3b) Impose difficult verification on the

attacker and defender (weak/slow)

•PBKDF2([salt] + [password], c=10,000,000);

•Use PBKDF2 when FIPS certification or

enterprise support on many platforms is required

•Use Scrypt where resisting any/all hardware

accelerated attacks is necessary but enterprise

support and scale is not.

Password Storage in the Real World](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/webapplicationsecurity-170215130603/75/Web-application-Security-40-2048.jpg)