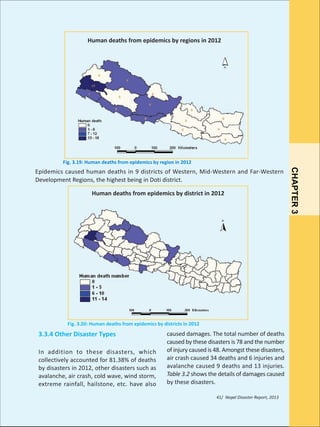

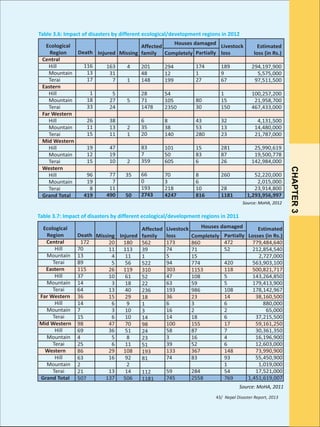

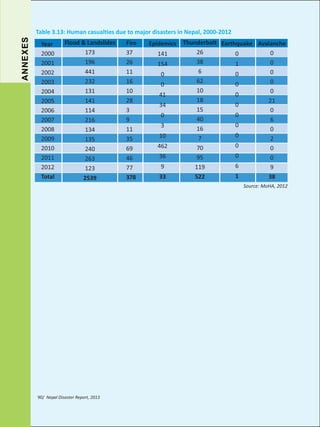

This document provides a summary of Nepal's 2013 disaster report. It was published jointly by Nepal's Ministry of Home Affairs and the Disaster Preparedness Network-Nepal. The report documents Nepal's disaster management initiatives in 2012-2013, analyzes disaster trends, and highlights good practices in community-based disaster mitigation. It focuses on participation and inclusion in disaster risk reduction. The report is intended to serve as a reference for stakeholders and help improve disaster management policies, planning, and community resilience in Nepal.