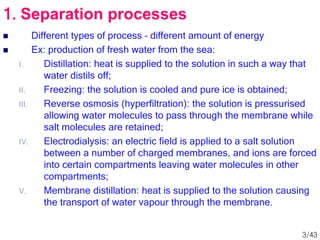

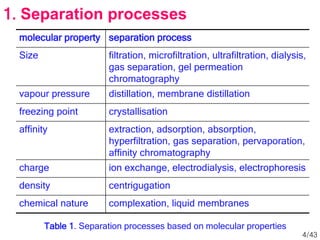

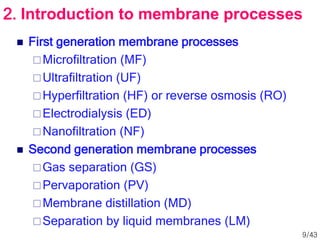

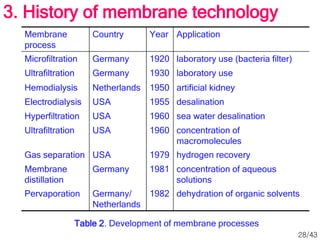

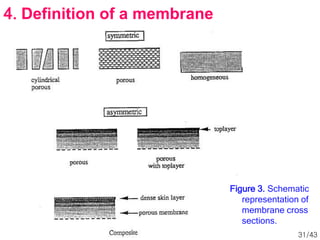

Membrane technology has evolved significantly over time. Early membrane studies date back to the 18th century, but membranes saw little industrial use until the mid-20th century. Major breakthroughs include the 1959 invention of the Loeb-Sourirajan reverse osmosis membrane, which enabled desalination at practical throughput. Other processes like gas separation were enabled by composite membranes with a thin selective top layer. While membrane types existed earlier, applications like membrane distillation have only recently been implemented at large scale.