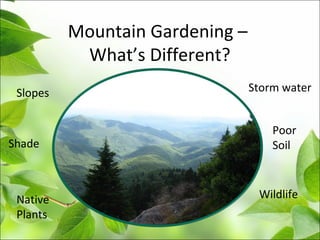

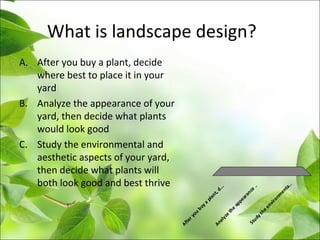

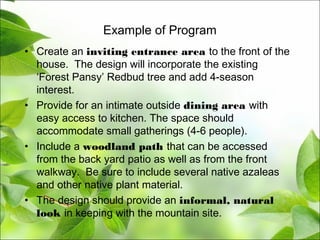

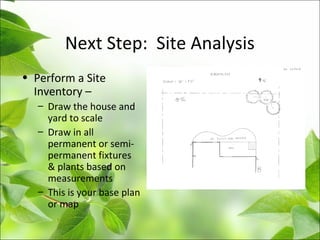

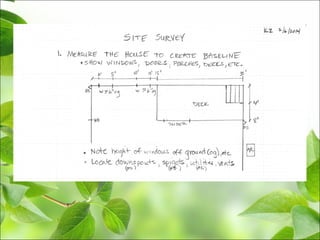

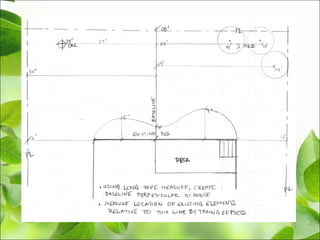

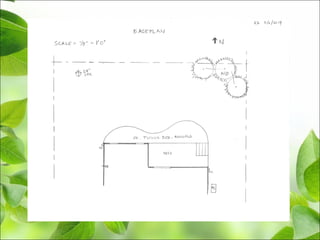

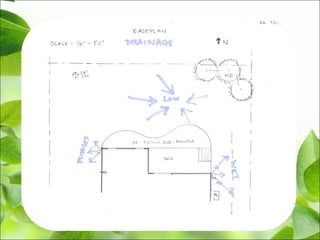

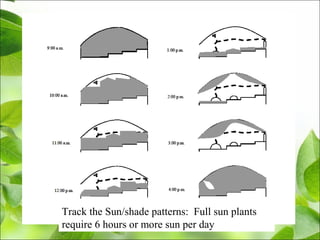

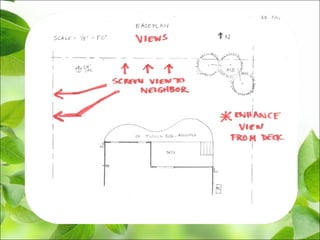

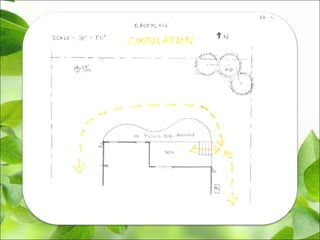

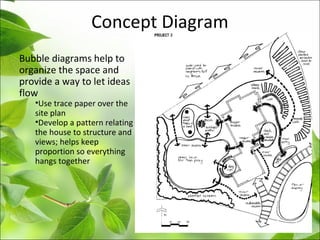

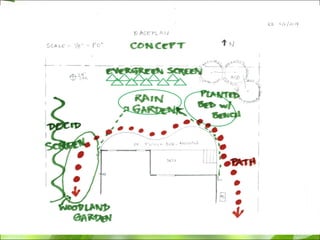

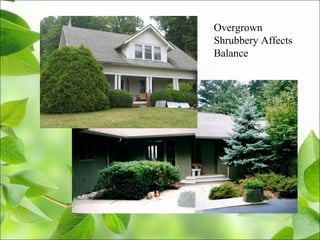

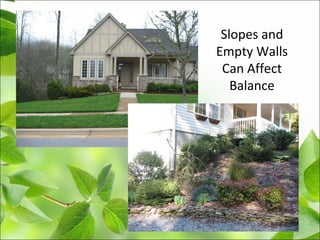

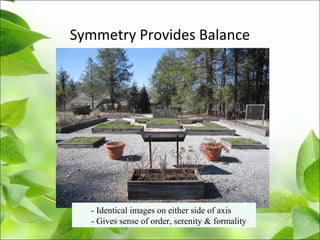

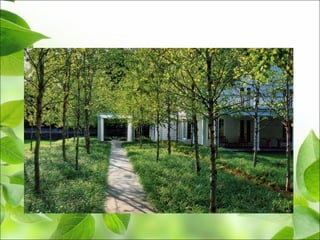

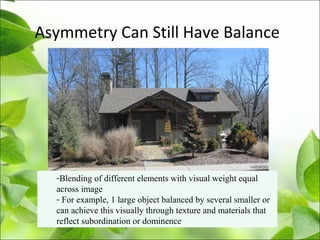

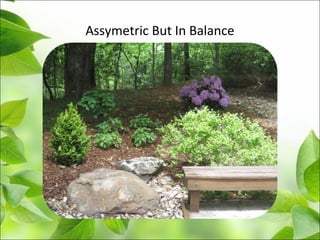

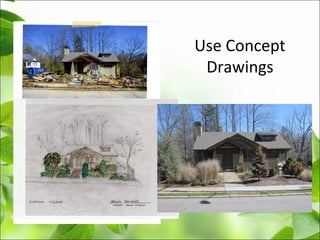

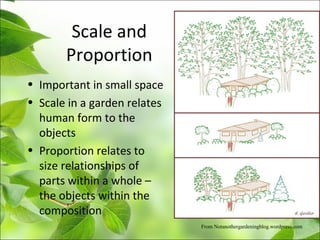

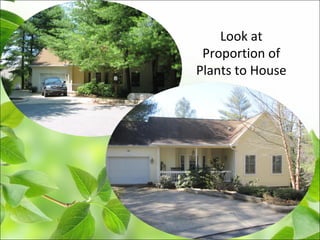

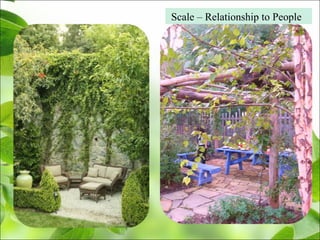

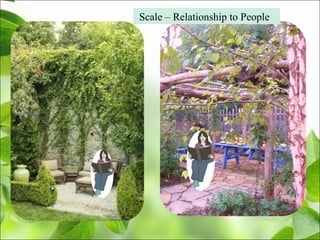

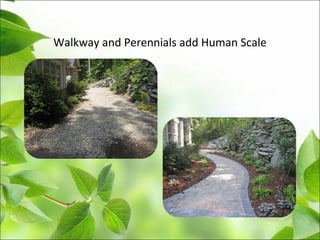

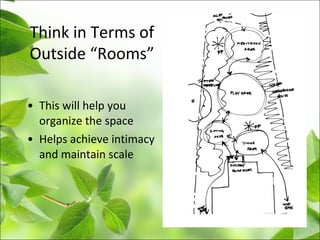

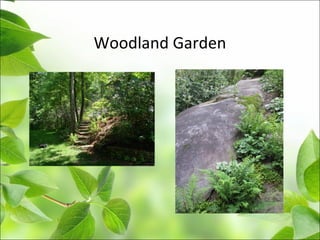

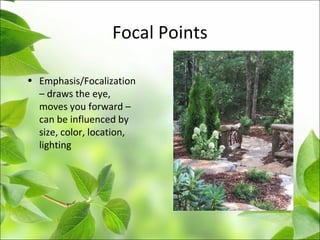

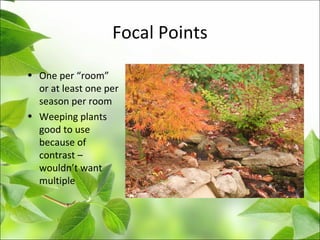

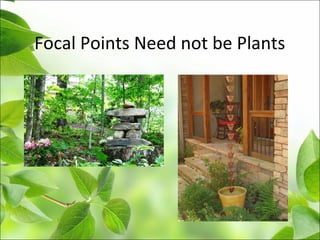

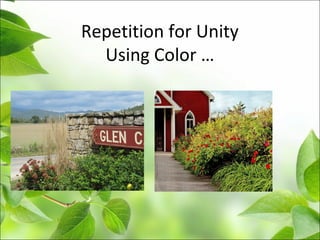

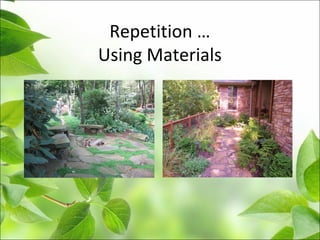

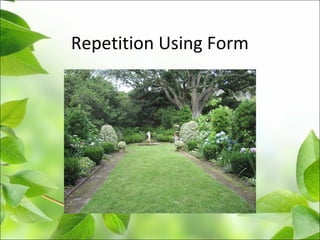

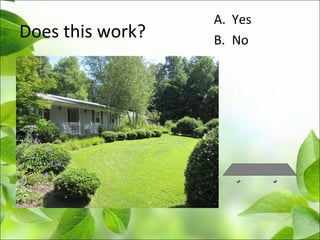

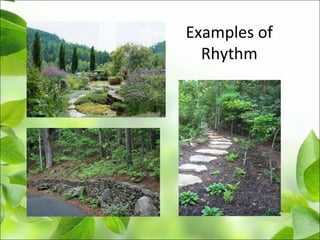

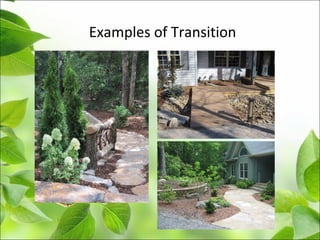

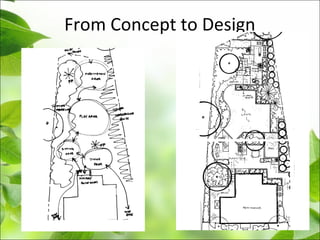

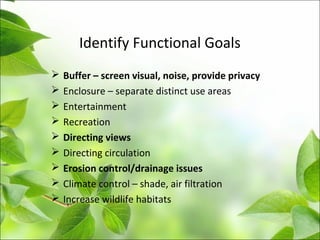

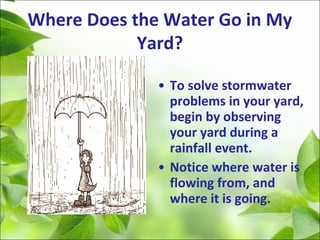

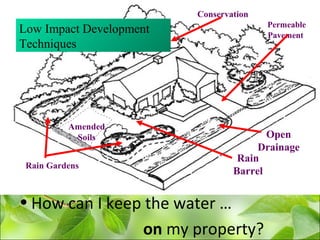

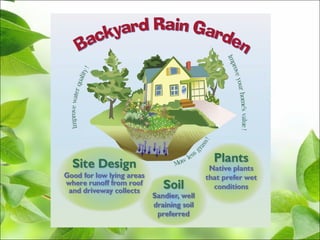

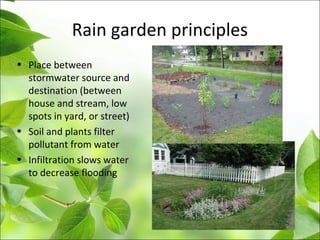

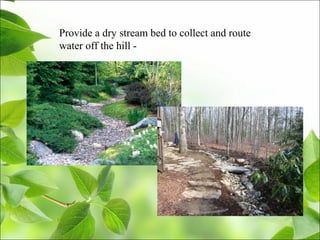

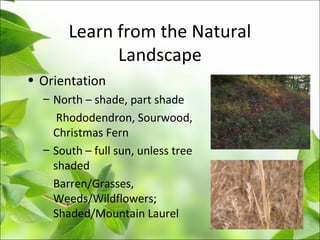

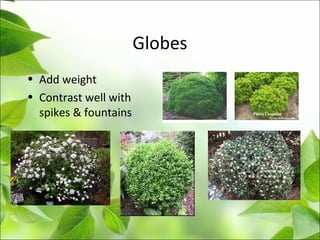

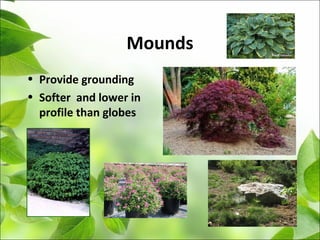

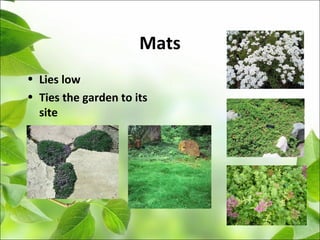

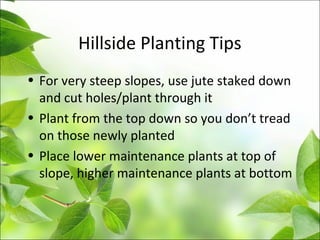

This document provides guidance on landscape design for mountain properties. It discusses key considerations for mountain gardens including slopes, shade, stormwater, and native plants. The steps of the landscape design process are outlined, beginning with determining property goals and needs, performing a site analysis to identify conditions, developing a concept plan, and addressing design elements like balance, scale, and focal points. Functional goals for the design like erosion control and increasing wildlife habitat are also covered.