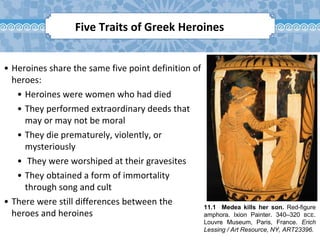

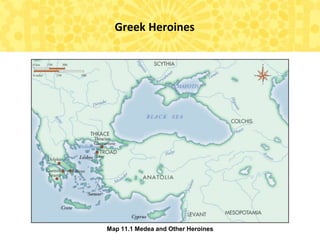

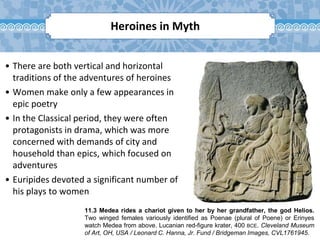

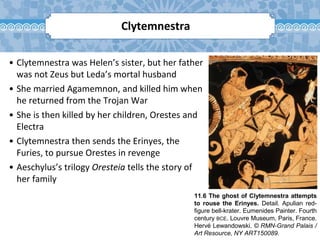

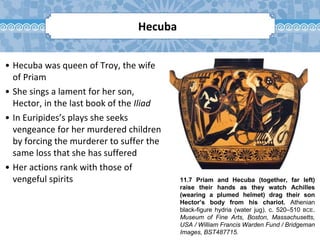

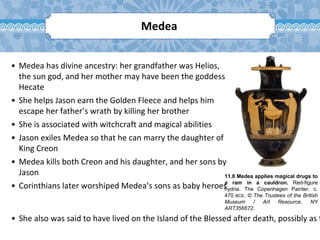

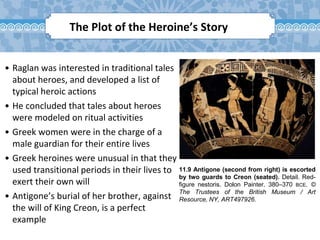

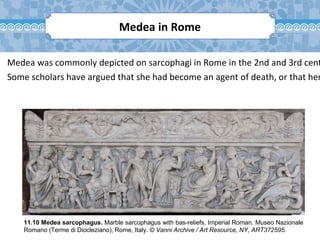

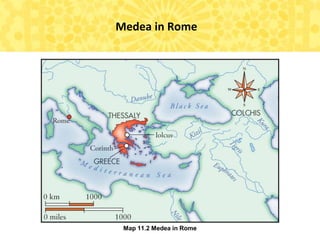

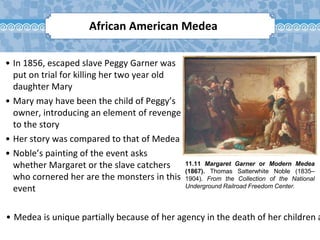

This document discusses Greek heroines and the myth of Medea in three parts. It begins by outlining five traits shared by Greek heroines, including that they performed extraordinary deeds and obtained immortality through song and cult. It then examines Medea's story and role as a heroine, noting her divine ancestry and acts of killing her brother and sons. The document concludes by exploring how Medea has been received and interpreted in different contexts, such as in Roman art and literature and more modern African American works that draw parallels between Medea and the experiences of slaves.