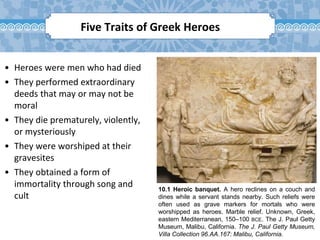

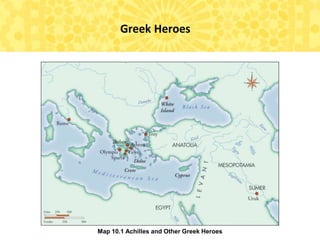

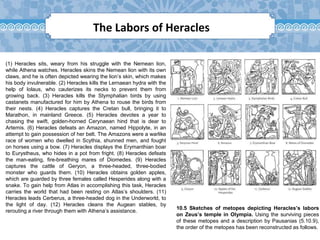

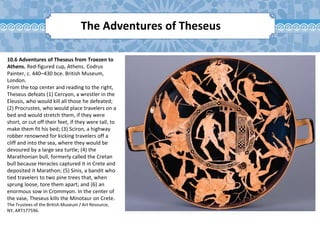

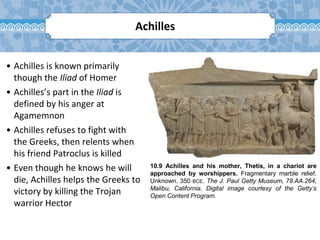

This document provides an overview of Greek heroes based on a chapter from a textbook. It discusses the key traits of heroes like Achilles, including that they performed extraordinary deeds and obtained immortality through song and cult. It also examines specific heroes like Heracles, Theseus, Oedipus, and Achilles, detailing their myths and how they were portrayed. It analyzes heroes in contexts like cult, myth, and reception in poetry about war. Heroes served as models for understanding human experiences like the emotions of soldiers.