This document provides an overview of the Greek gods Demeter and Hades and their associated myths. It discusses:

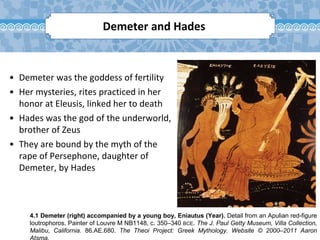

- Demeter as the goddess of fertility and her connection to death through her mysteries celebrated at Eleusis.

- Hades as the god of the underworld and his role in the myth of abducting Persephone, Demeter's daughter.

- Rituals and beliefs surrounding death and the underworld in ancient Greece, including funerary practices and the division of the underworld.

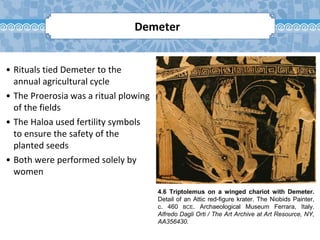

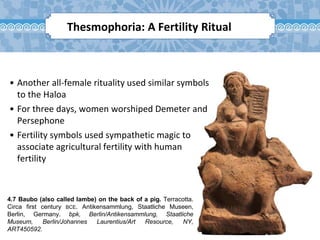

- Demeter's rituals connected to the agricultural cycle like the Proerosia and Haloa performed by women.

- The Eleusinian mysteries and Demeter's demand