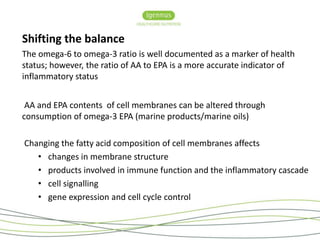

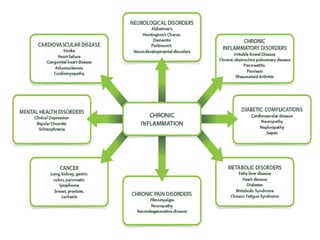

This document summarizes a presentation on managing chronic inflammation through modulating fatty acids like omega-3 and arachidonic acid. It discusses how inflammation contributes to diseases like cancer and dementia, and how biomarkers like the omega-3 index, omega-6/omega-3 ratio, and AA/EPA ratio can be used to personalize omega-3 dosing to reduce inflammation. Clinical evidence suggests EPA in particular may help treat inflammation and inhibit cancer progression by competing with arachidonic acid metabolism.

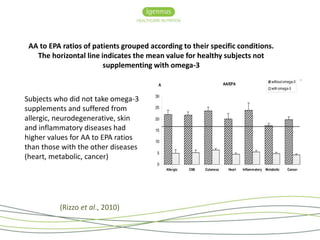

![AA to EPA ratio in health and disease

Fasted blood samples from 1432 [Italian] subjects, who were referred by

their physicians, were analysed to assess their AA to EPA and total omega-6 to

omega-3 ratios in whole blood and in RBC membrane phospholipids

Individuals with no diagnosable conditions had lower AA to EPA ratios than

those with diagnosable health conditions

Individuals with allergic, skin and neurodegenerative diseases had higher

ratios of AA to EPA compared to the values for subjects with other

pathologies, possibly due to a higher turnover of EPA

Subjects who did not take omega-3 supplements and suffered from allergic,

neurodegenerative, skin and inflammatory diseases had higher values for AA

to EPA ratios than those with the other diseases (heart, metabolic, cancer)

(Rizzo et al., 2010)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/camexpotalk-141007101644-conversion-gate02/85/Managing-Chronic-Inflammation-24-320.jpg)

![AA to EPA ratio and the metabolic syndrome

High AA to EPA ratio associated with insulin resistance

Age and visceral fat accumulation correlated significantly with serum AA to

EPA ratio

Subjects with visceral fat accumulation ≥100 cm2 had higher serum AA to

EPA ratio (but not DHA to AA or [EPA+DHA] to AA) and more likely to have

metabolic syndrome and history of coronary artery disease, compared to

those with visceral fat accumulation <100 cm2 (Inoue et al., 2013)

“The balance of AA to EPA by lifestyle modification and medication (such as

EPA-based medications) could be useful in reducing the prevalence of the

metabolic syndrome and atherosclerosis” (Inoue et al., 2013)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/camexpotalk-141007101644-conversion-gate02/85/Managing-Chronic-Inflammation-27-320.jpg)

![High AA to EPA ratio and high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are directly

correlated with severity of depression, lower RBC membrane omega-3 and especially

EPA are associated with the severity of depression (Adams et al., 1996; Conklin et al.,

2007) and distinguish between anxious and non-anxious forms of major depressive

disorder (Liu et al., 2013)

Depression [in the elderly] is characterised by very low levels of omega-3, in

particular of EPA, in RBC membranes and a high AA to EPA ratio compared to healthy

subjects (Rizzo et al., 2012)

Omega-3 intervention lowers AA to EPA ratio and is correlated with improved scores

on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (Rizzo et al., 2012)

Omega-3 Index (mean, 3.9% vs 5.1%) and individual omega-3 fatty acids were

significantly lower in major depressive disorder patients. An Omega-3 Index < 4%

was associated with high concentrations IL-6 (indicative of an elevated cardiovascular

risk profile (Baghai et al., 2011)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/camexpotalk-141007101644-conversion-gate02/85/Managing-Chronic-Inflammation-45-320.jpg)

![Summary

Western dietary and lifestyle factors, particularly those that create an

inflammatory environment, contribute significantly to inflammatory related

disorders

Diets that are high in omega-6 increase ‘risk’, whilst diets that are rich in long-chain

omega-3 may reduce the ‘risk’

Specifically, a high AA to EPA ratio and low EPA [rather than DHA] appears to

be associated with many inflammatory conditions

Modifying the diet can reduce systemic inflammation by manipulating the AA

to EPA ratio](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/camexpotalk-141007101644-conversion-gate02/85/Managing-Chronic-Inflammation-52-320.jpg)

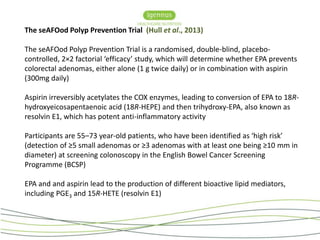

![Summary

Human intervention studies show inconsistent findings – is there a need

for personalising omega-3 fatty acid dosing for clinical outcomes?

Not all ‘fish oils’ are the same – acknowledge the significance of the EPA to

DHA ratio

Pure EPA is a safe adjunctive therapy for inflammatory disorders

Evidence suggests that the presence of DHA within the therapeutic oil may

be [in some conditions] undesirable

Pure EPA, because of its safety and known anti-cancer benefits, is now

entering phase III human trials as a chemopreventive agent

Pure EPA is recognised for its cardiovascular health benefits](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/camexpotalk-141007101644-conversion-gate02/85/Managing-Chronic-Inflammation-53-320.jpg)