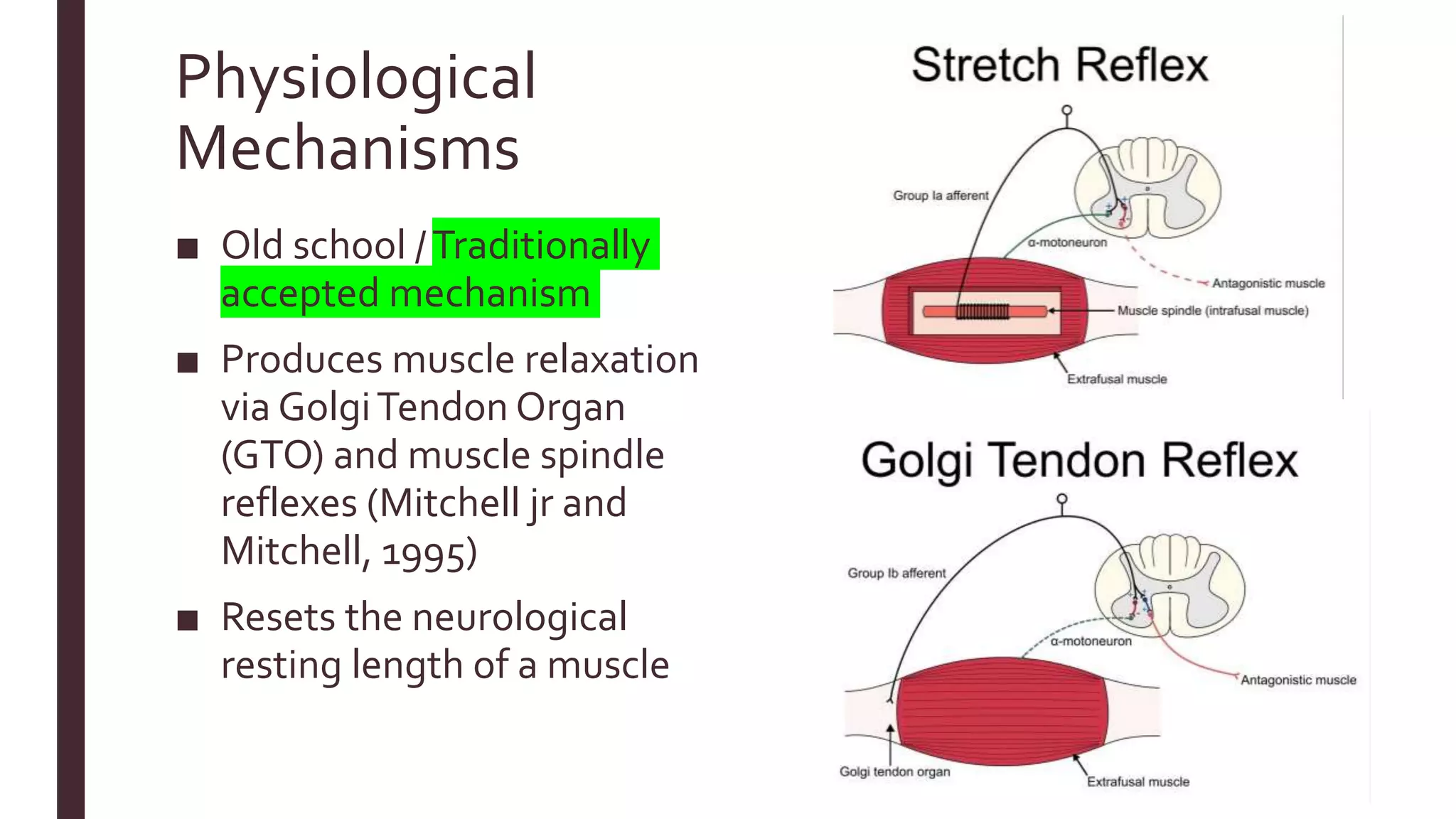

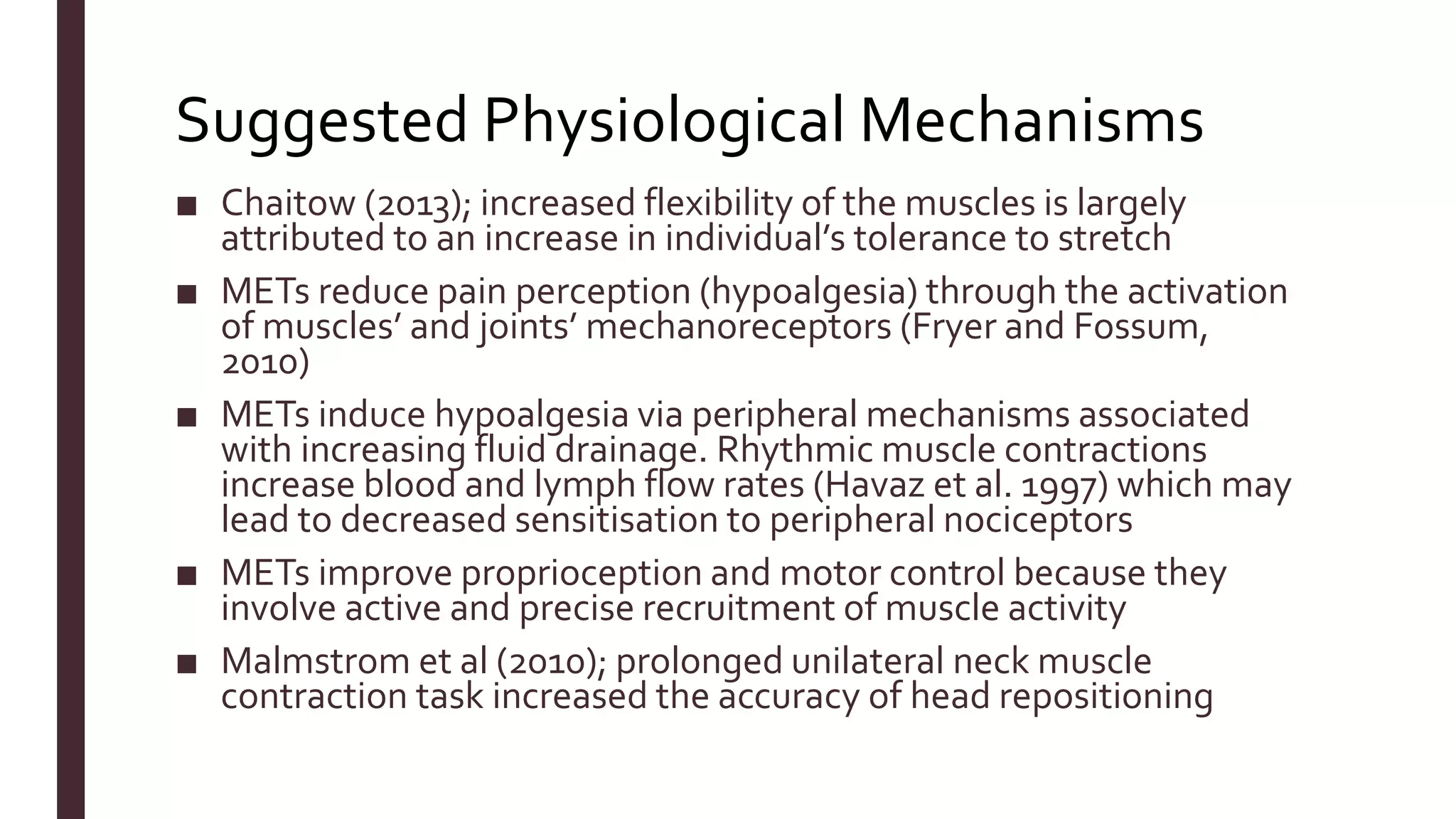

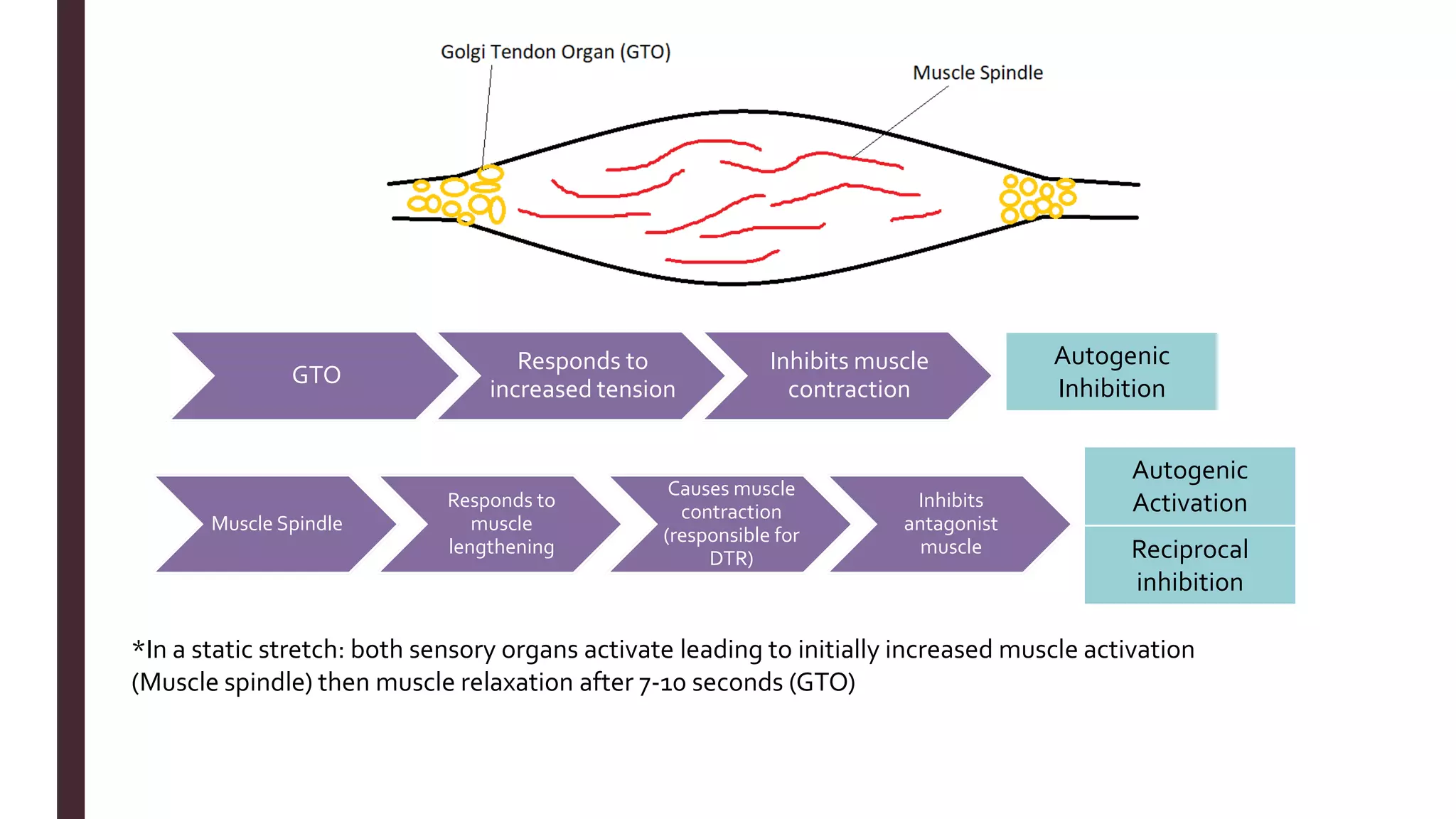

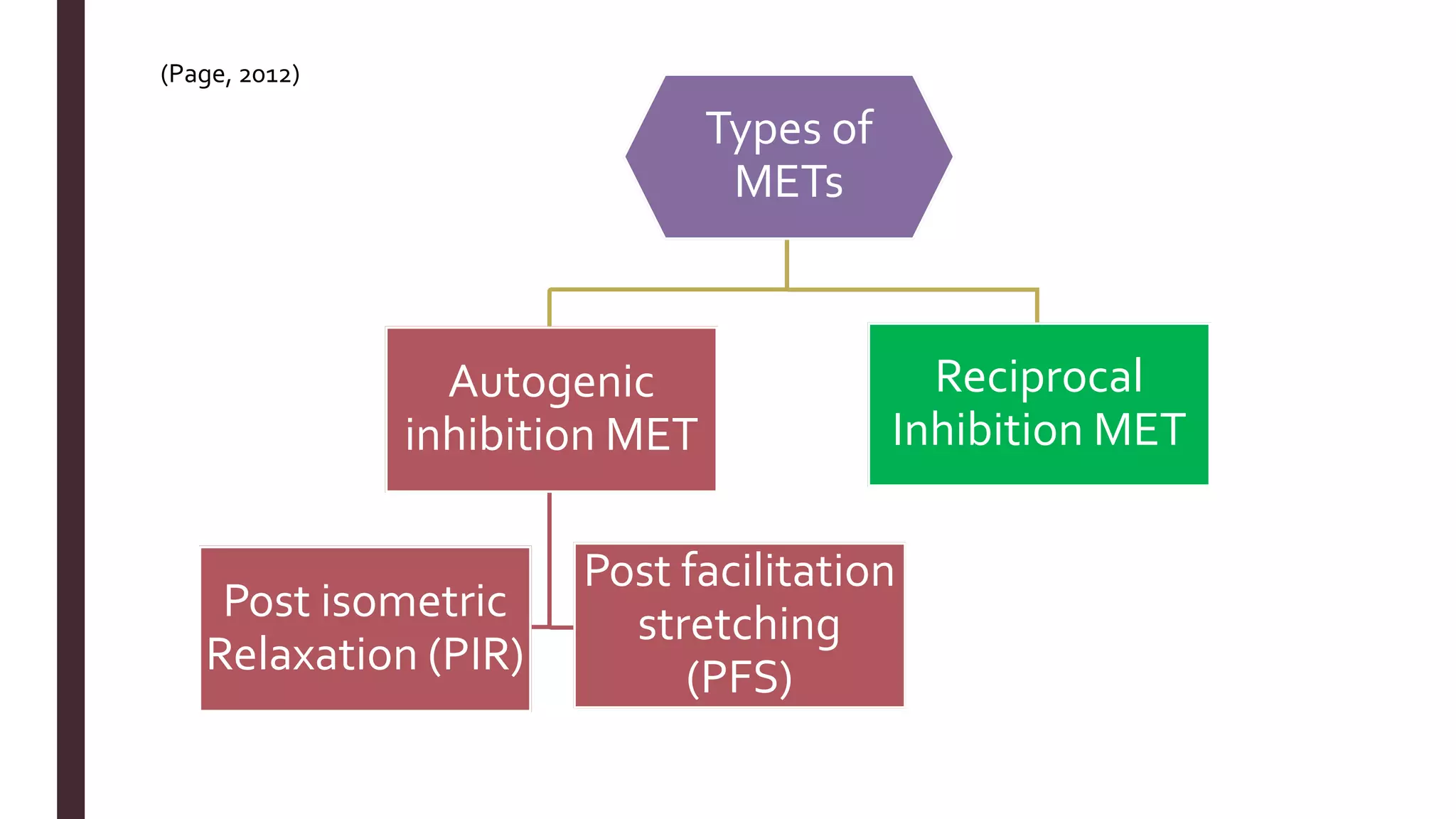

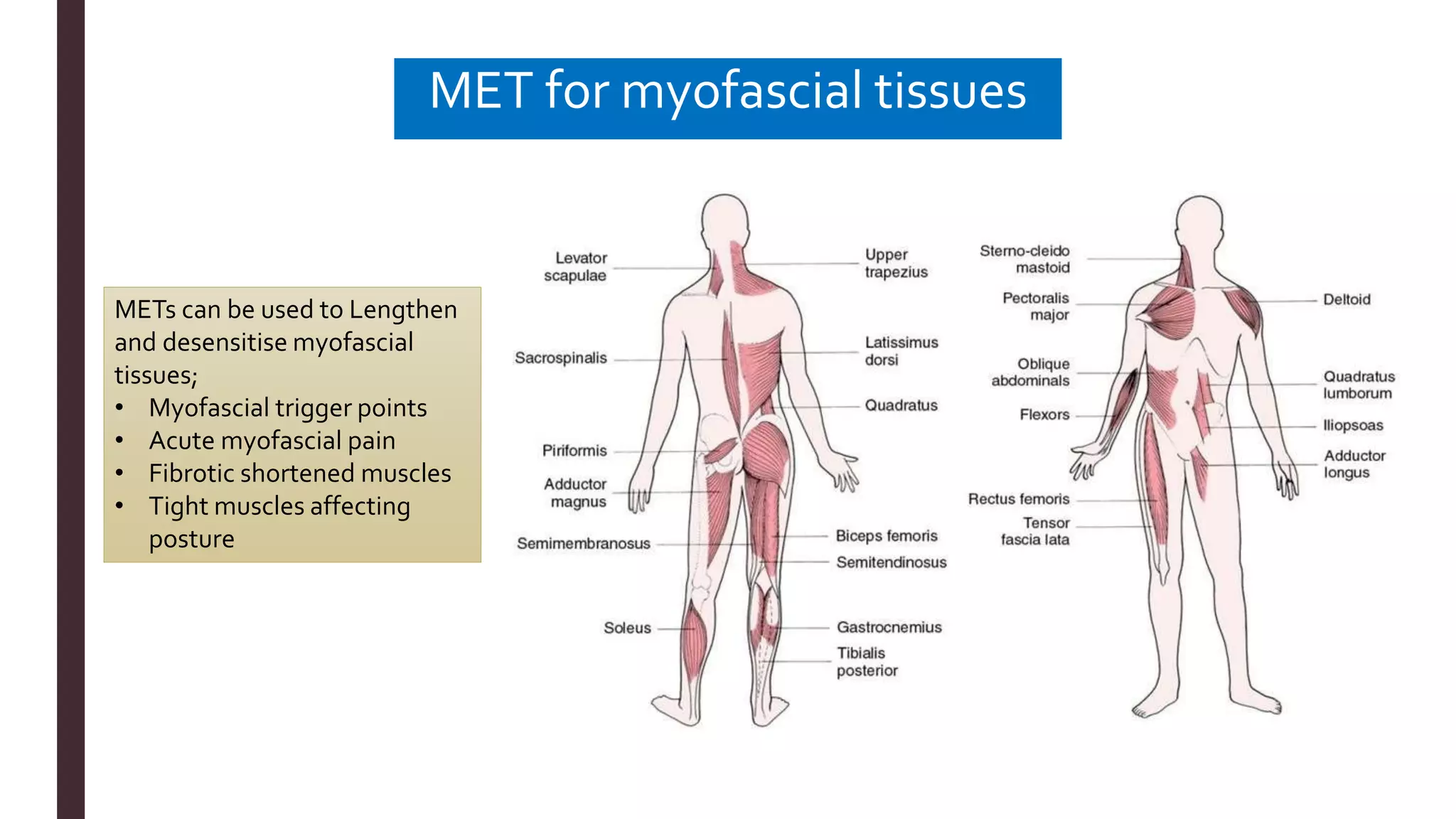

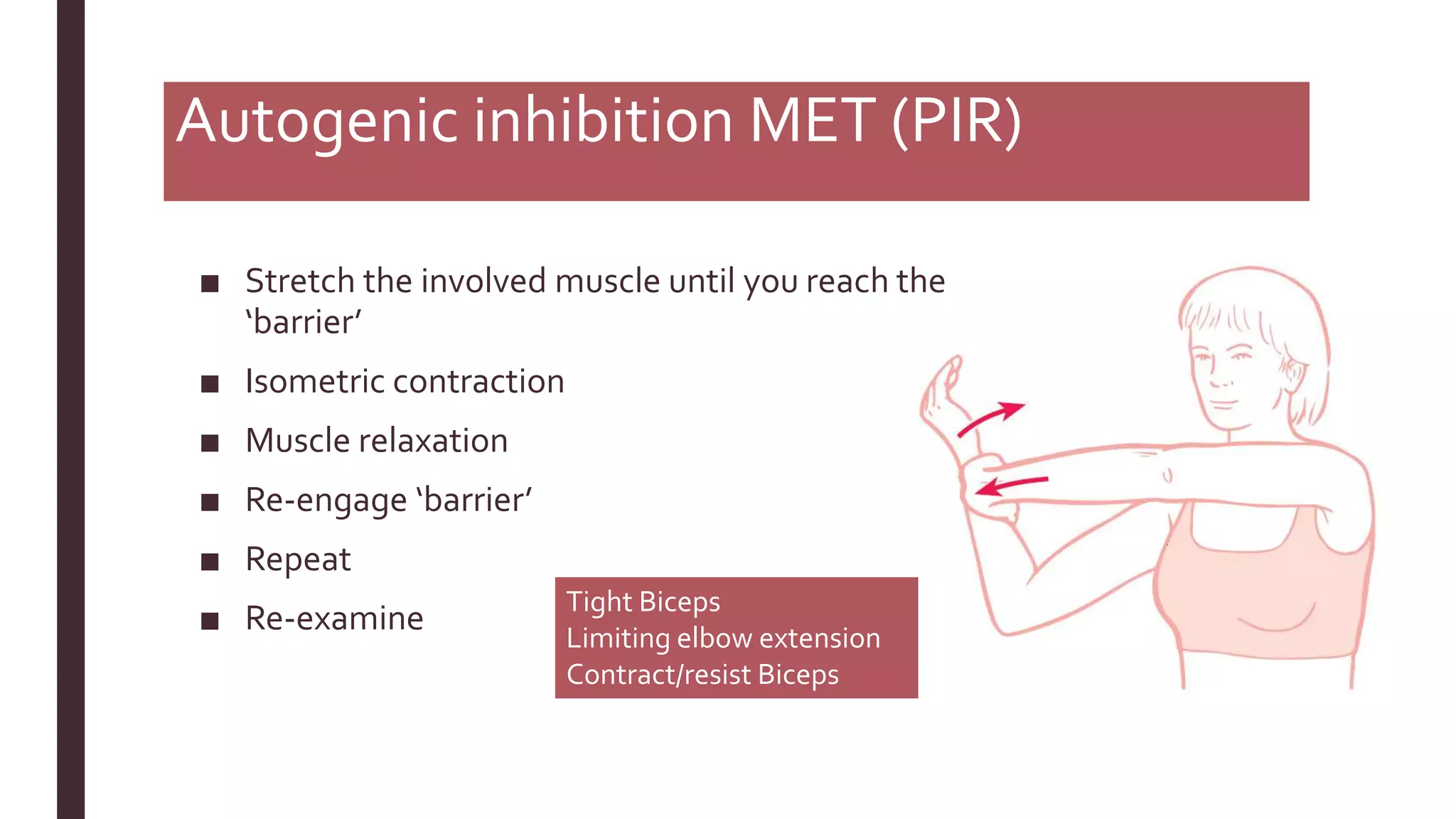

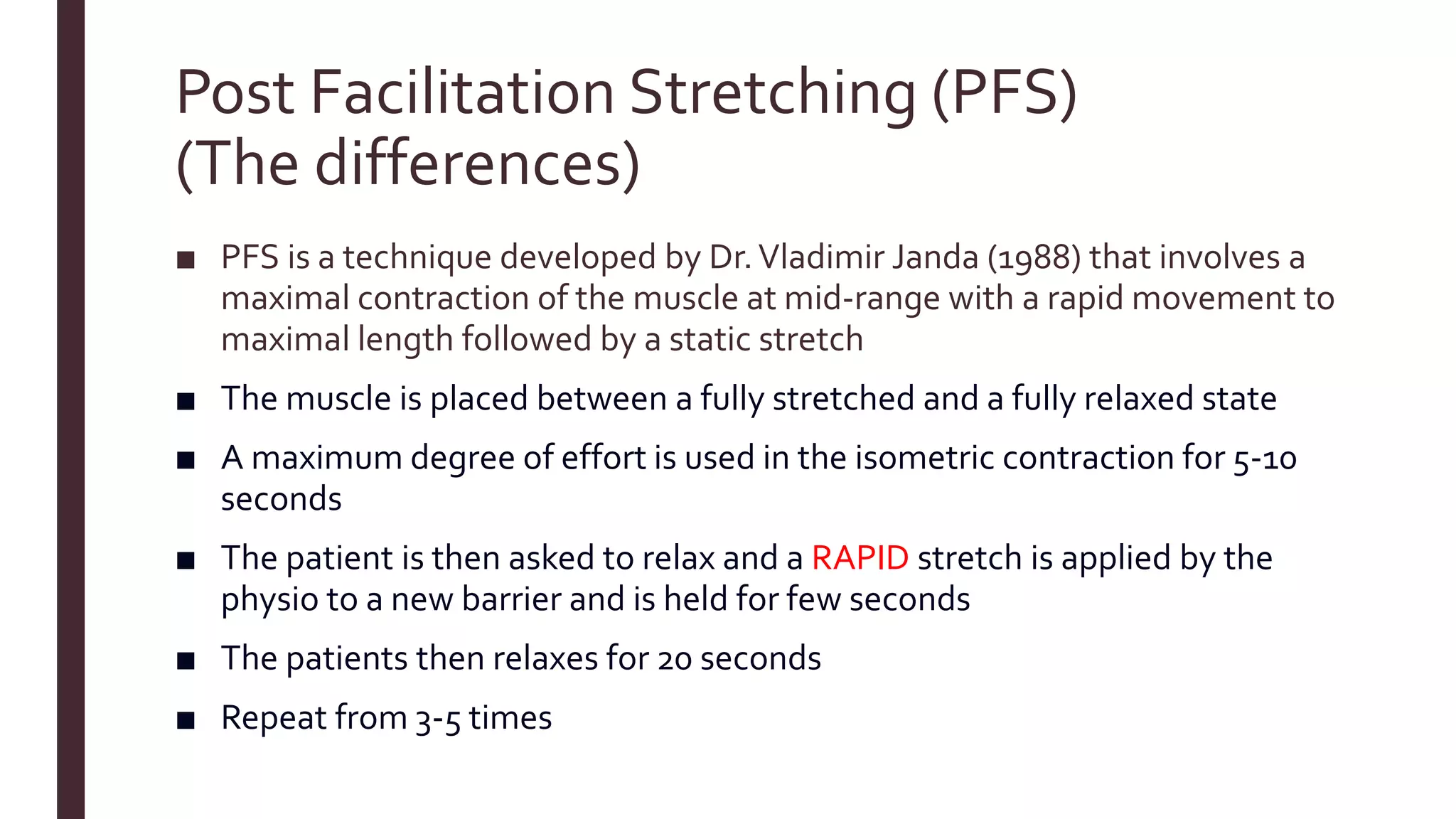

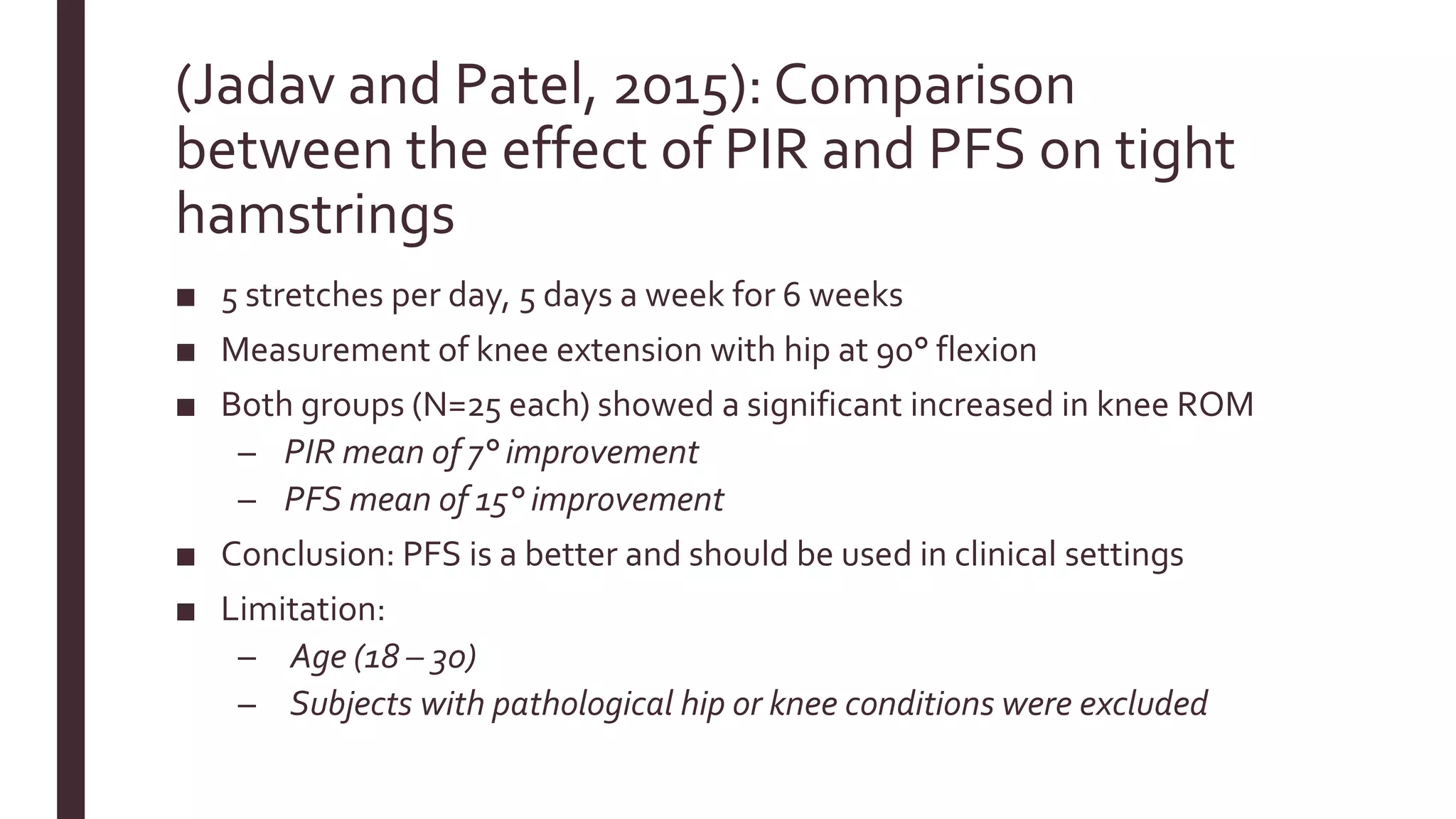

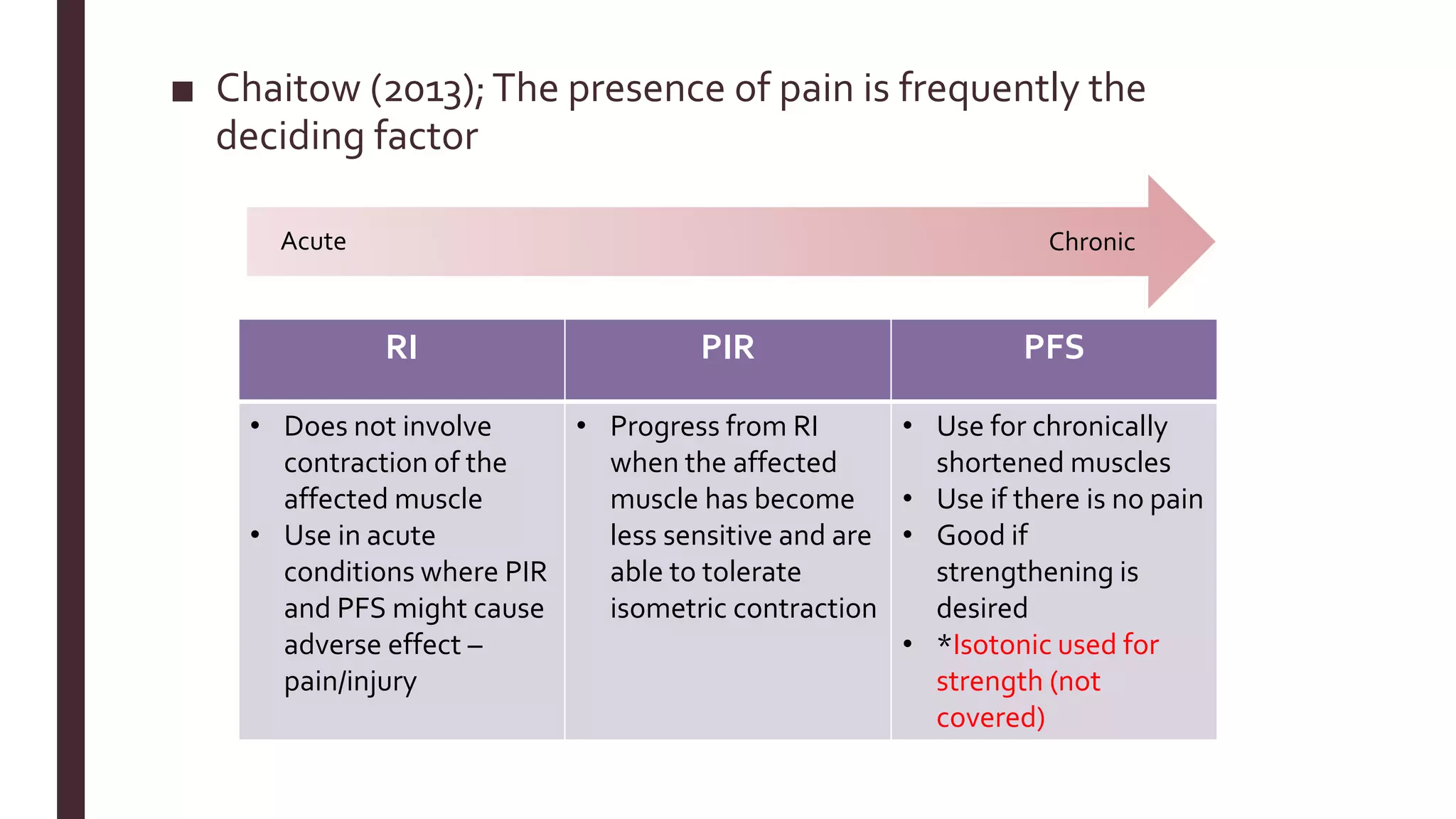

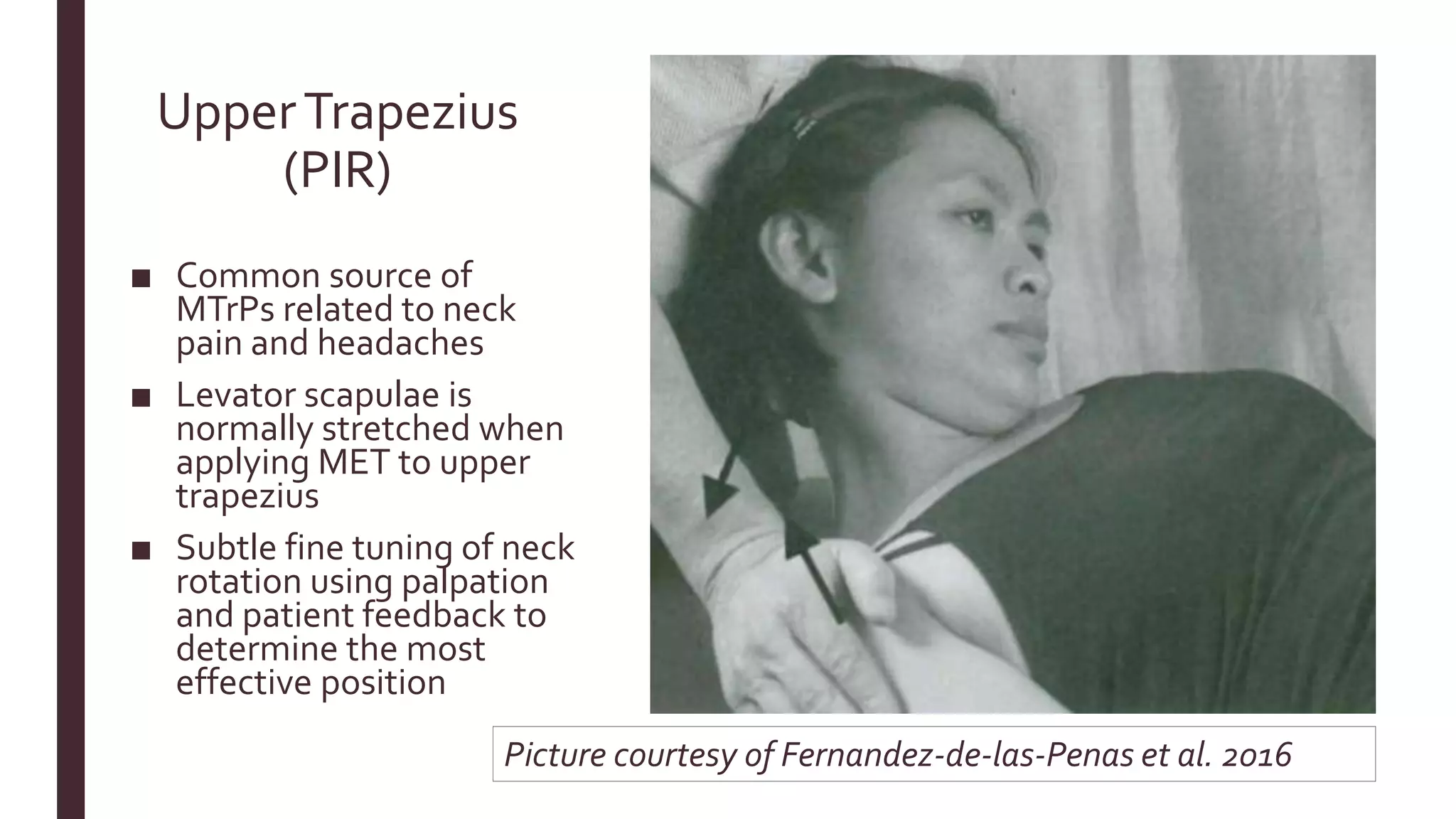

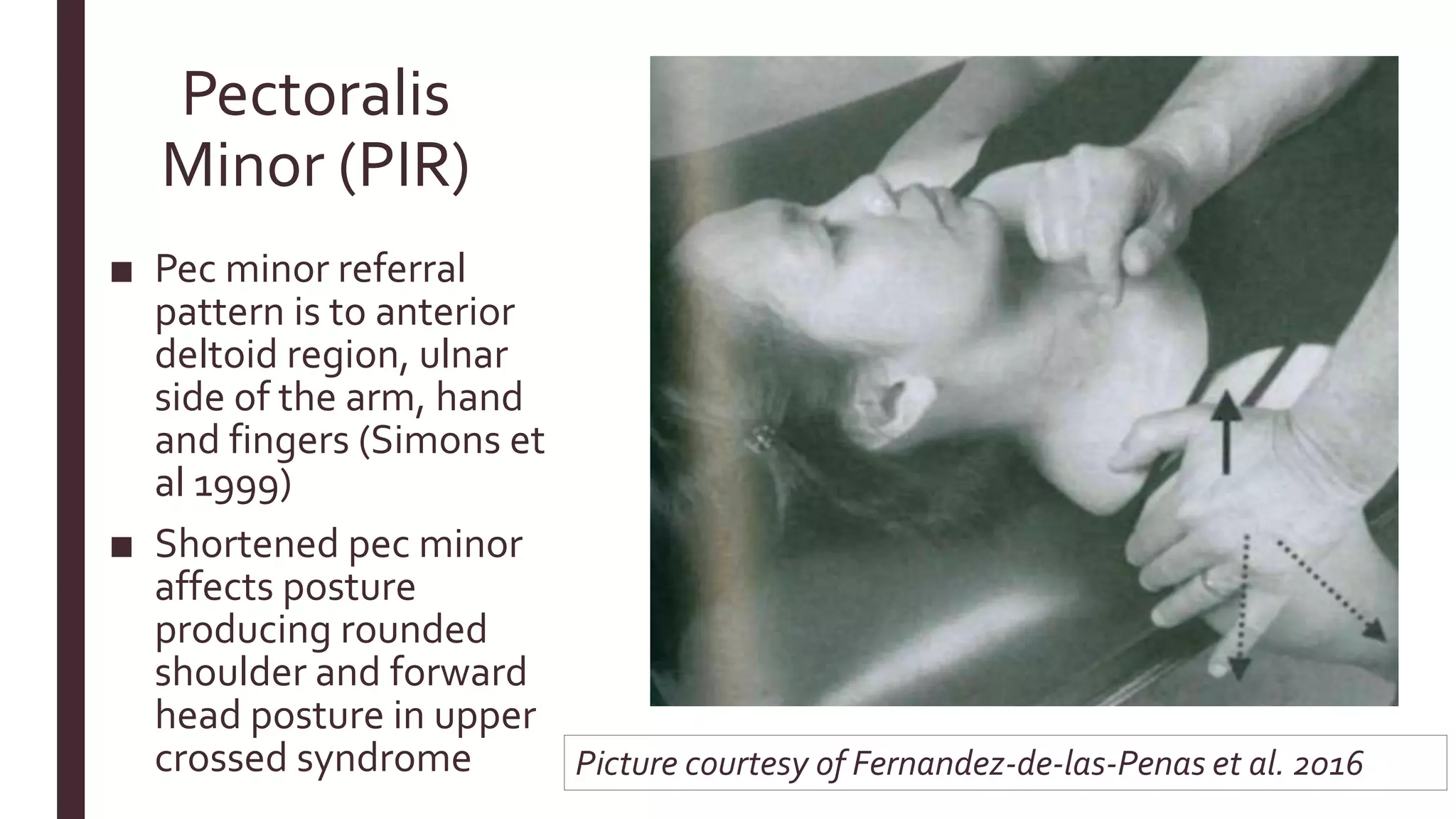

The document outlines Muscle Energy Techniques (METs), a system of manual procedures utilizing active muscle contraction from the patient to treat various musculoskeletal issues. It describes how these techniques work, their physiological mechanisms, different types, application methods, potential errors, and contraindications. The document also compares the effectiveness of different METs, particularly focusing on post-isometric relaxation and reciprocal inhibition techniques for muscle relaxation and flexibility improvement.

![References

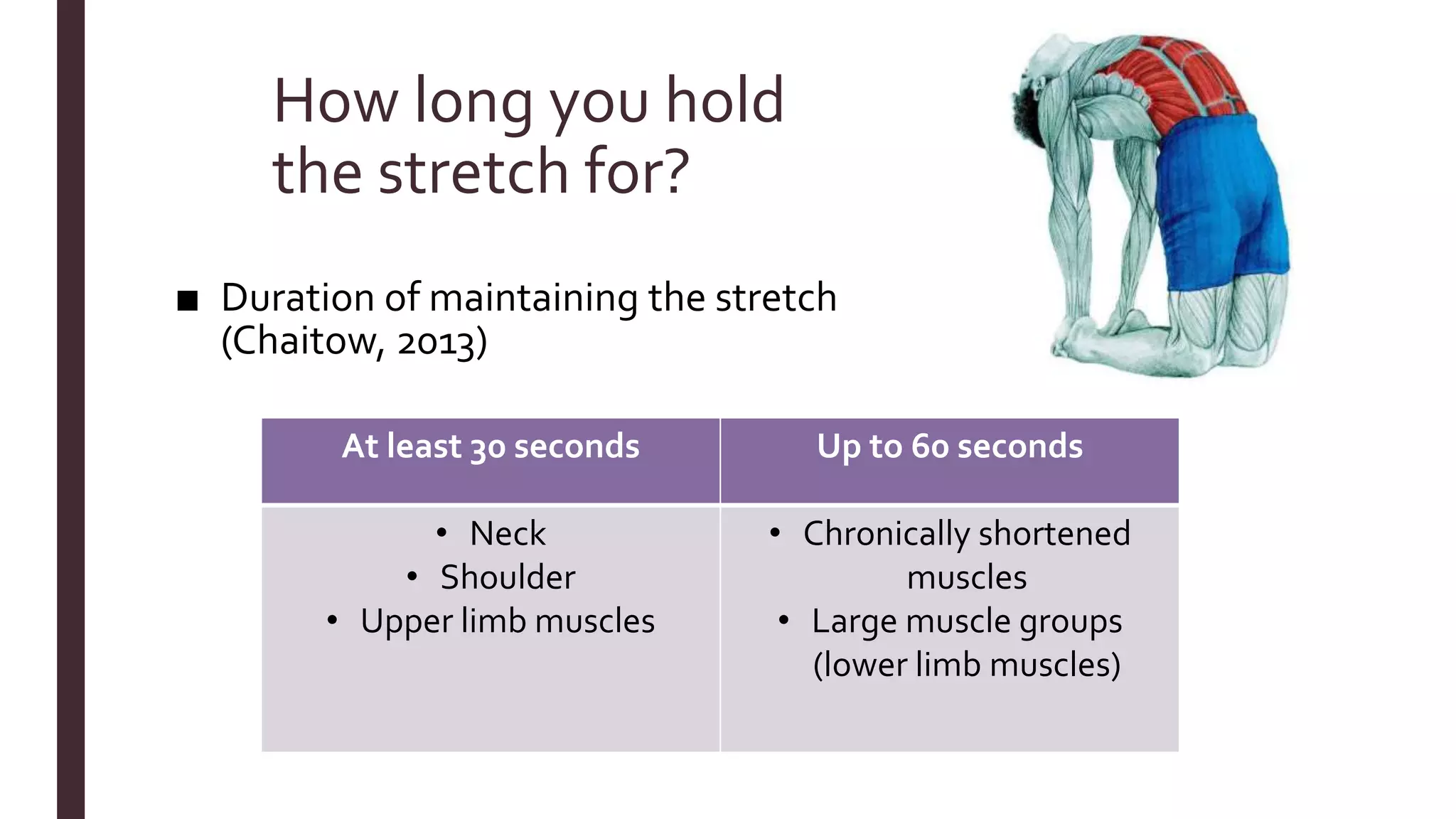

■ Chaitow, L. (2013). Muscle energy techniques. Elsevier Health Sciences.

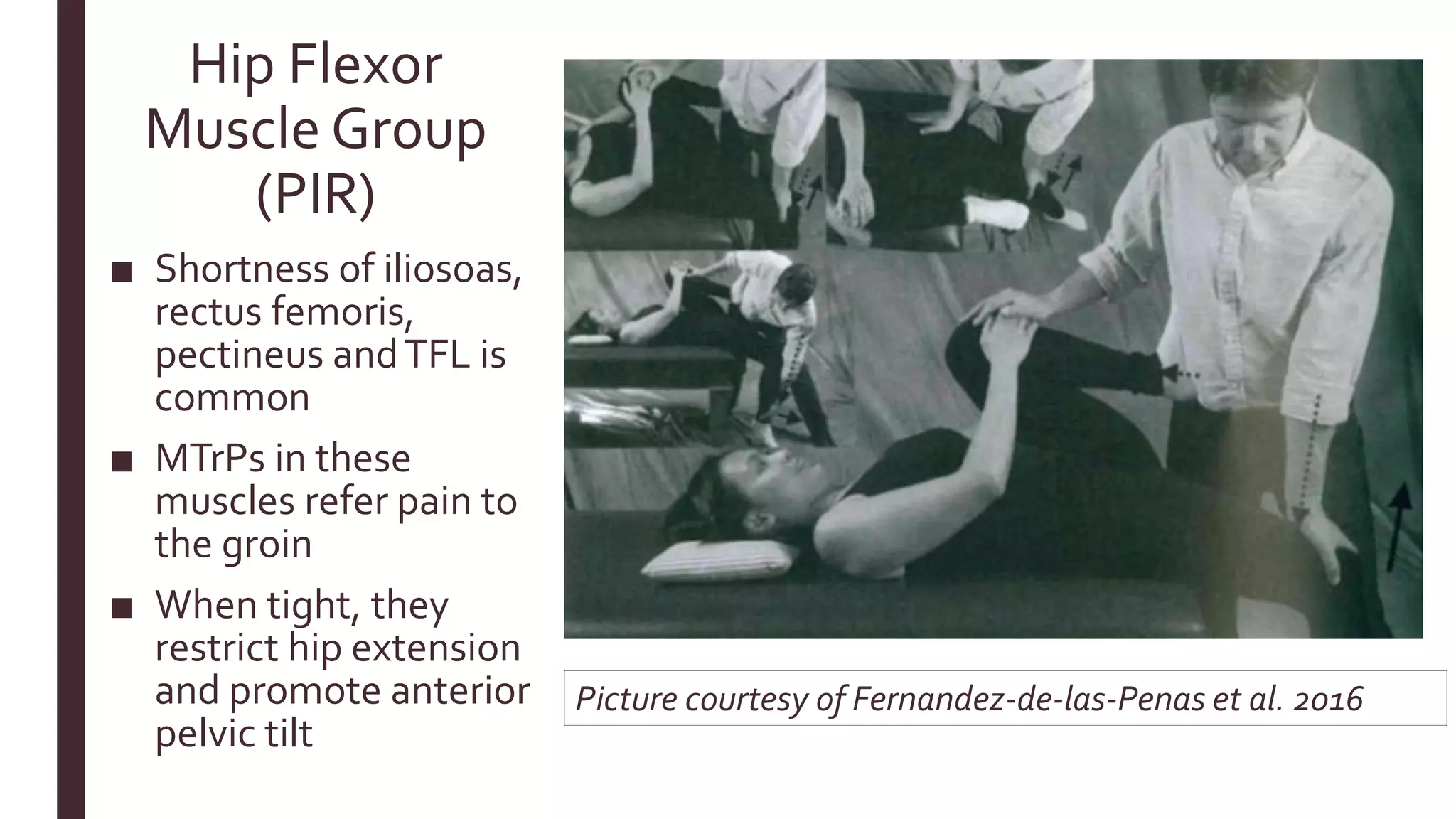

■ Fernández-de-las-Peñas,C., Cleland, J., & Dommerholt, J. (2016). Manual therapy for musculoskeletal pain syndromes.

[Erscheinungsort nicht ermittelbar]: Elsevier.

■ Fryer, G & Fossum (2010).Therapeutic mechanisms underlying muscle energy approaches. Cephalalgia. 28. 264-275.

■ Havas, E., Parviainen,T.,Vuorela, J.,Toivanen, J., Nikula,T., &Vihko,V. (1997). Lymph flow dynamics in exercising human

skeletal muscle as detected by scintography. TheJournal of physiology, 504(1), 233-239.

■ Jadav, M., & Patel, D. (2015). Comparison of effectiveness of post facilitation stretching and agonist contract-relax technique

on tight hamstrings. IndianJournal of PhysicalTherapy, 2(2), 70-75. [Online]

http://indianjournalofphysicaltherapy.in/ojs/index.php/IJPT/article/viewFile/56/59

■ Janda,V. (1988). Muscles and Cervicogenic Pain Syndromes. In PhysicalTherapy of theCervical andThoracic Spine, ed. R.

Grand. NewYork: Churchill Livingstone.

■ Malmström, E. M., Karlberg, M., Holmström, E., Fransson, P.A., Hansson, G. Å., & Magnusson, M. (2010). Influence of

prolonged unilateral cervical muscle contraction on head repositioning–decreased overshoot after a 5-min static muscle

contraction task. Manual therapy, 15(3), 229-234. [Online]

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1356689X09002082

■ Page, P. (2012). Current concepts in muscle stretching for exercise and rehabilitation. International journal of sports physical

therapy, 7(1), 109. [Online] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3273886/

■ Page, P., Frank, C., & Lardner, R. (2010). Assessment and treatment of muscle imbalance: the Janda approach. Human kinetics.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalversion-181104135522/75/Introduction-to-muscle-energy-techniques-METs-35-2048.jpg)