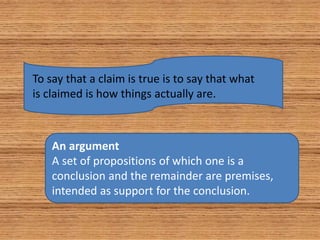

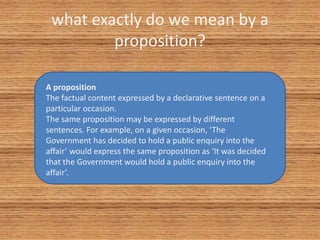

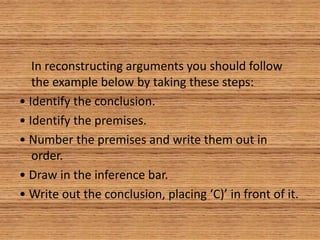

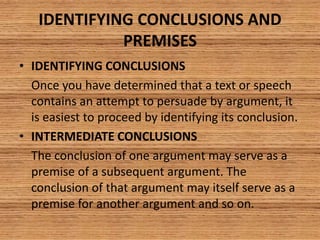

This document introduces arguments and critical thinking. It defines an argument as a set of propositions where one is the conclusion and the others are premises intended to support the conclusion. Arguments can be identified by finding the conclusion and premises. The conclusion of one argument can also serve as a premise for another argument. Critical thinking is important for citizens to properly evaluate moral, social, economic and political issues and have good reasons for what they believe.