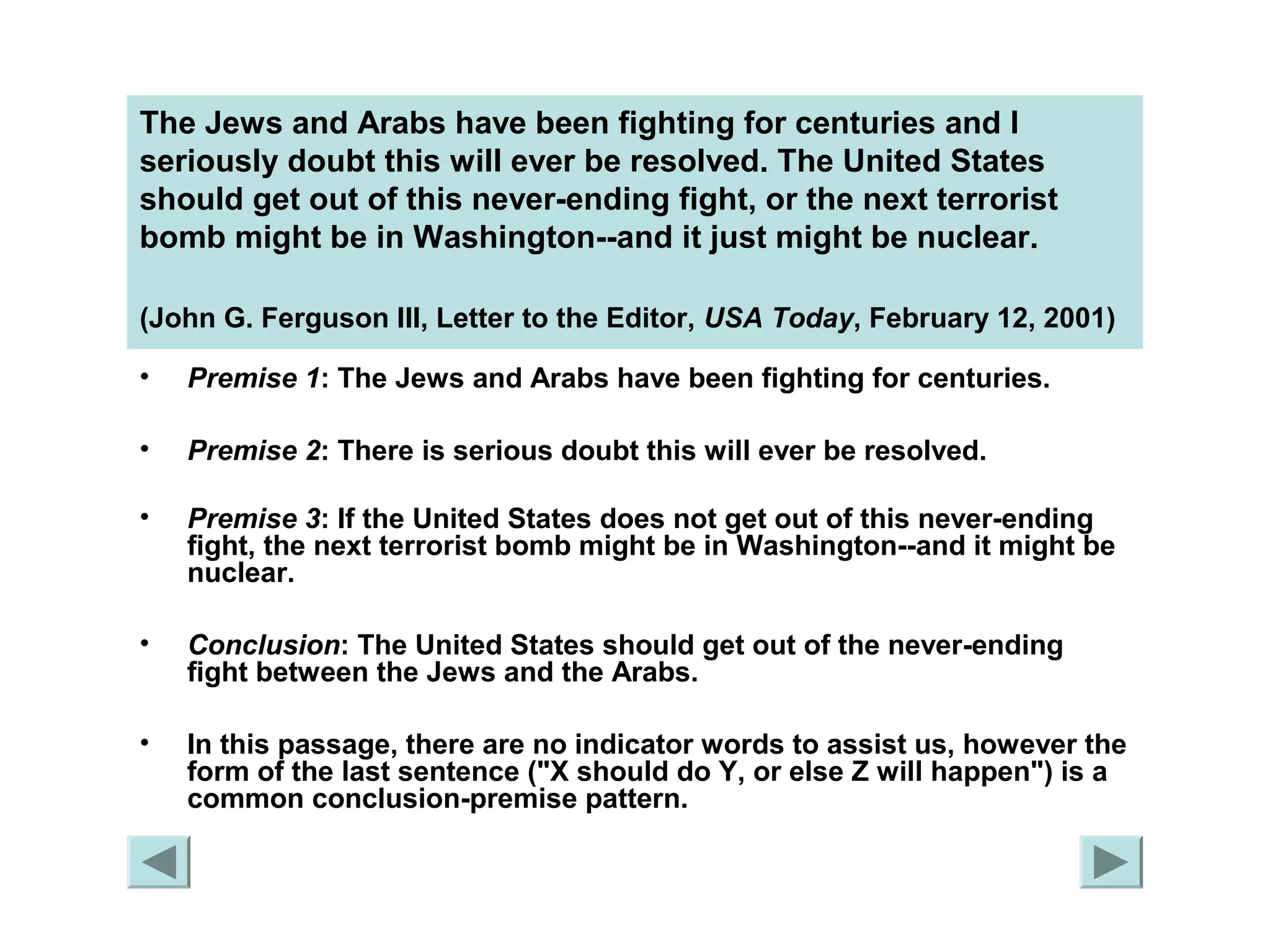

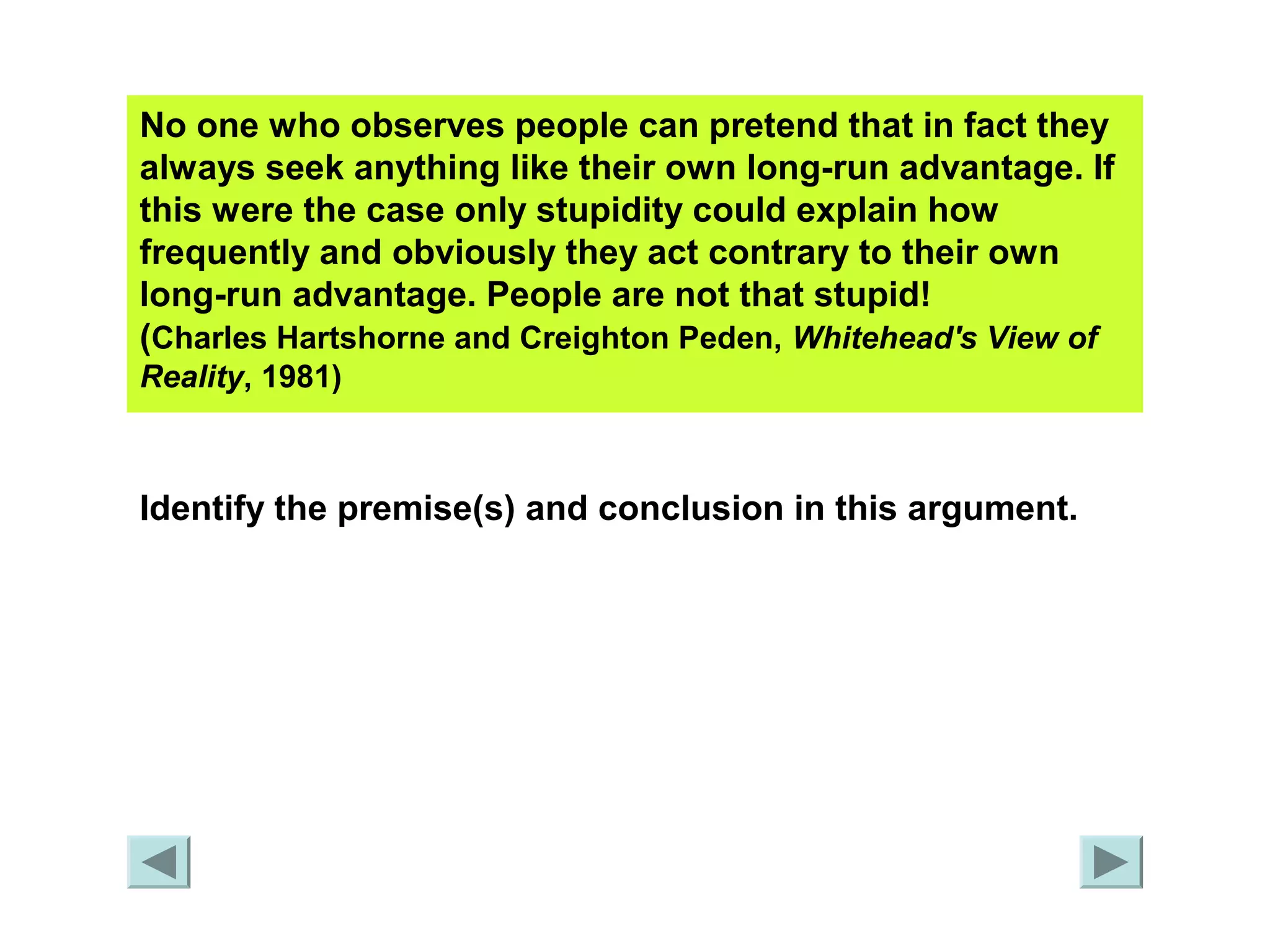

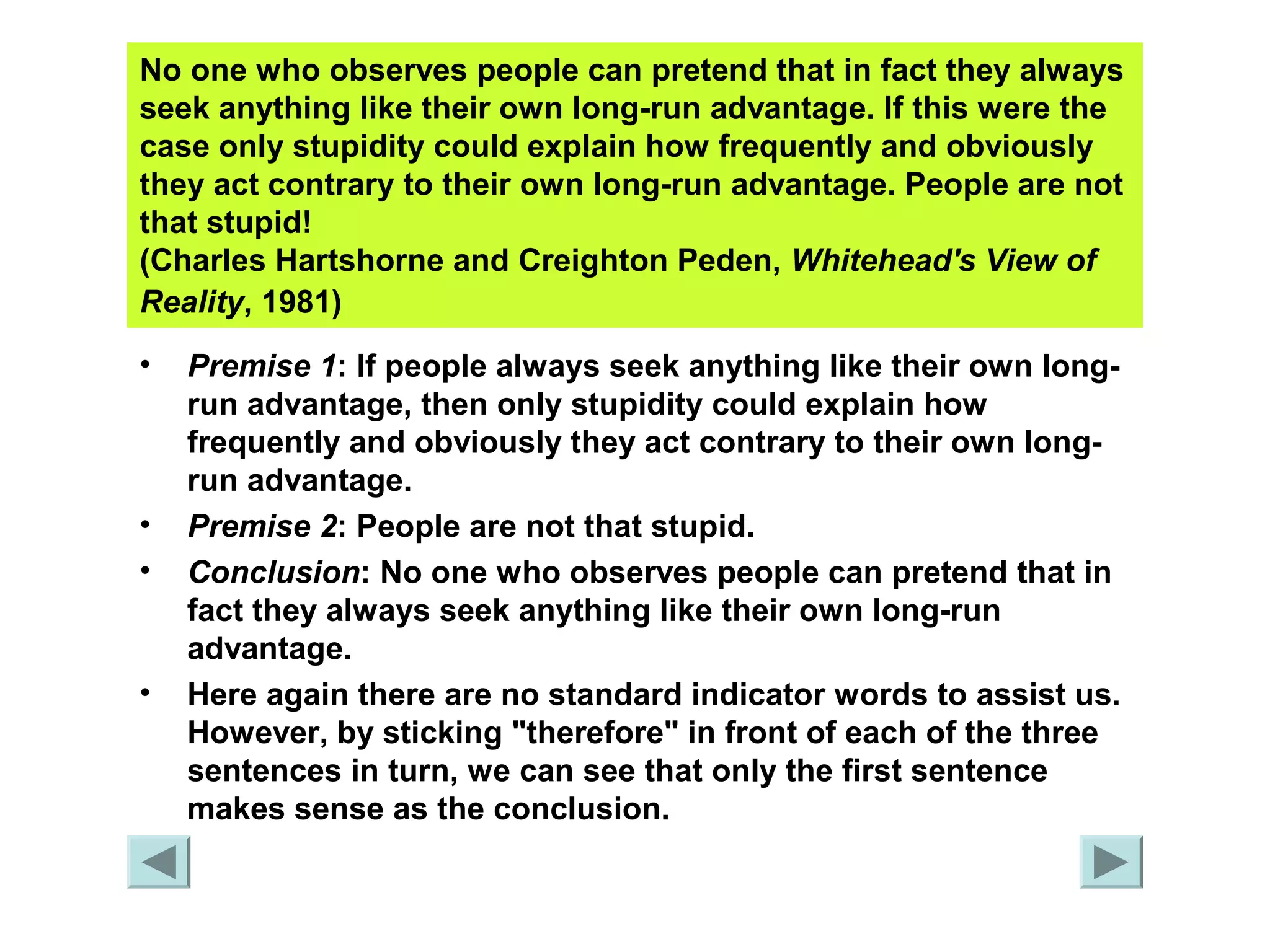

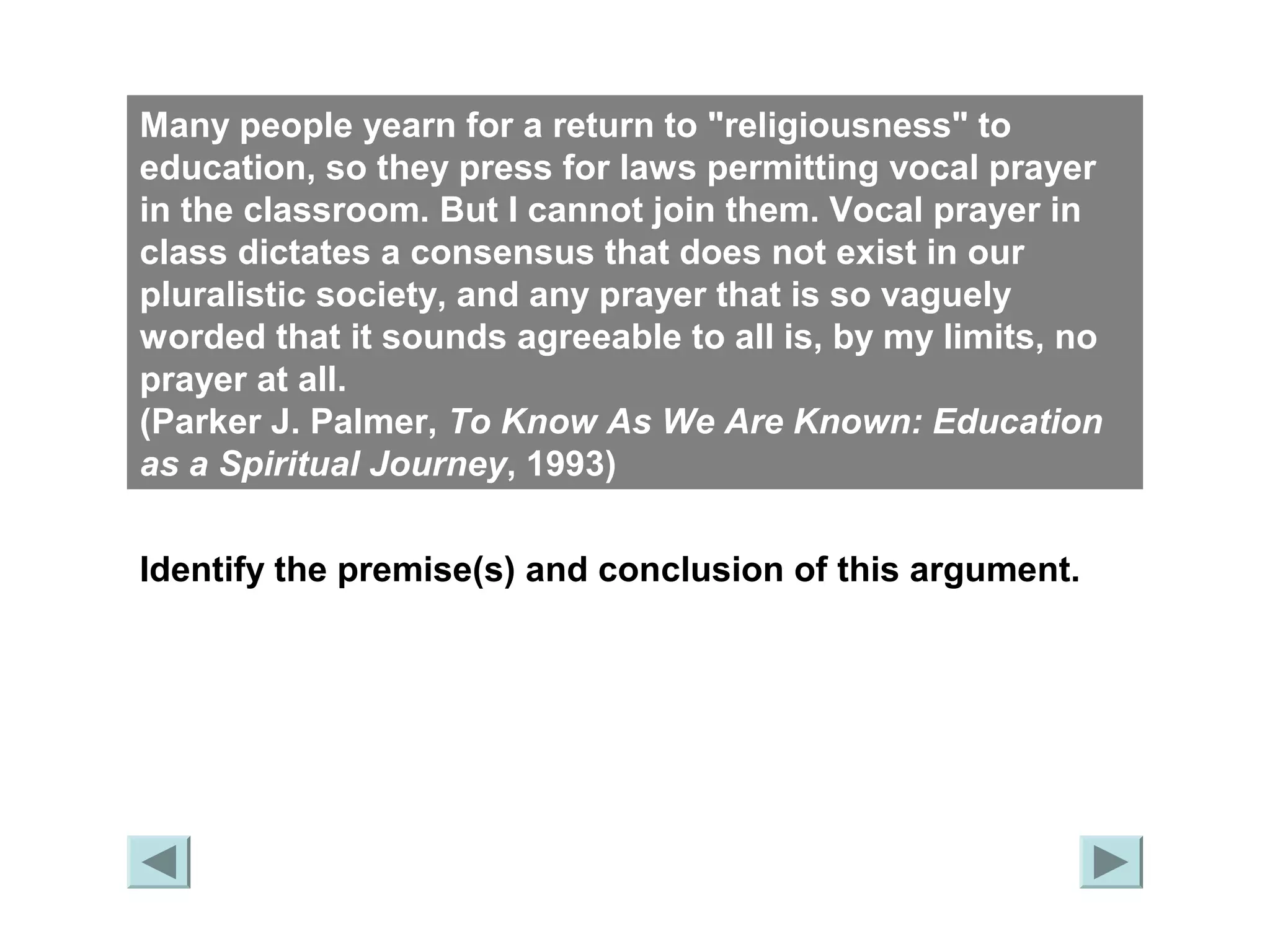

This document provides a tutorial on identifying premises and conclusions in arguments. It begins by giving examples of premises, conclusions, and argument structure. It then provides tips for distinguishing premises from conclusions, including looking for indicator words and testing statements with "therefore". The rest of the document gives practice identifying premises and conclusions in various arguments, demonstrating the application of the tips.

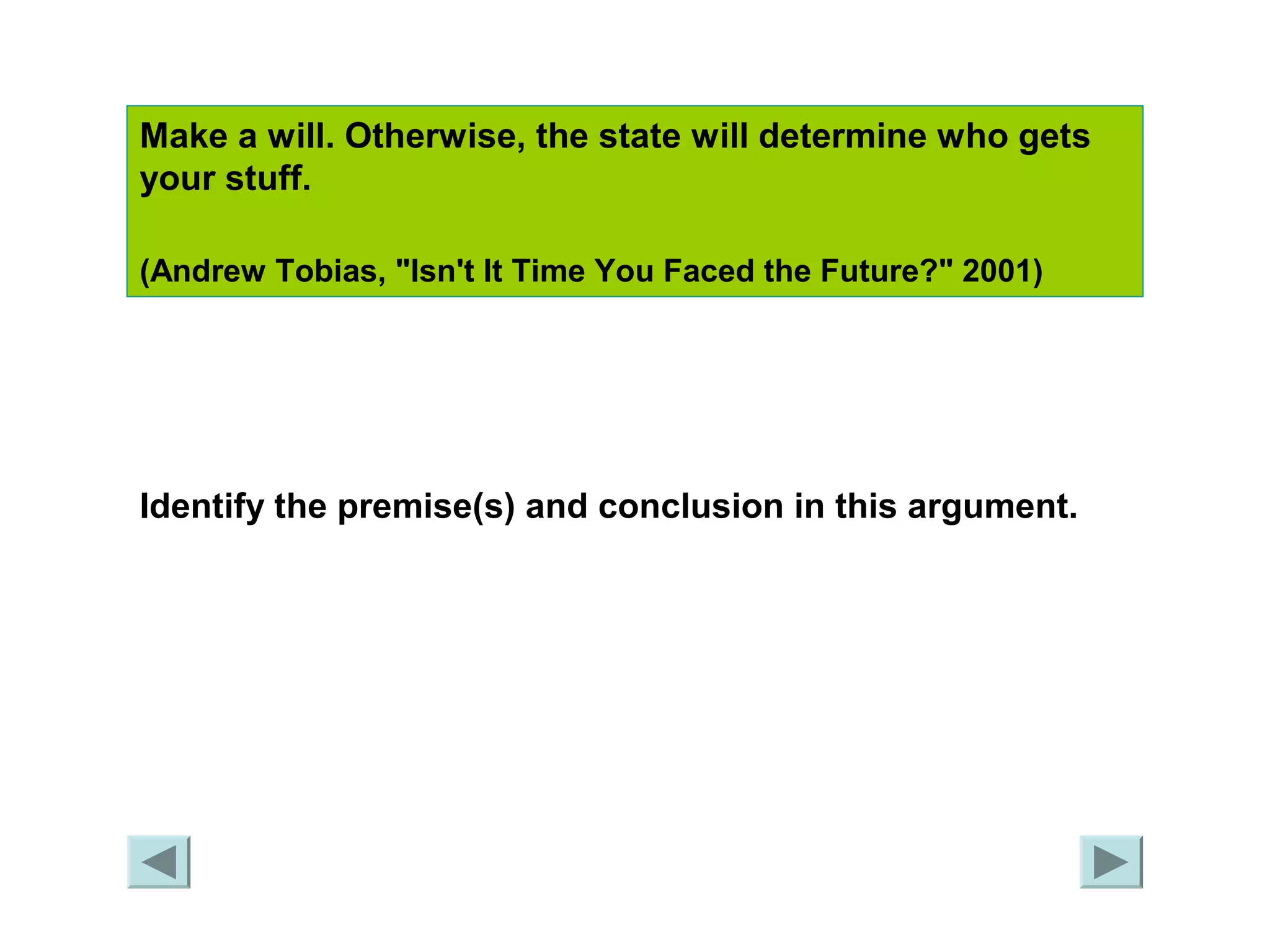

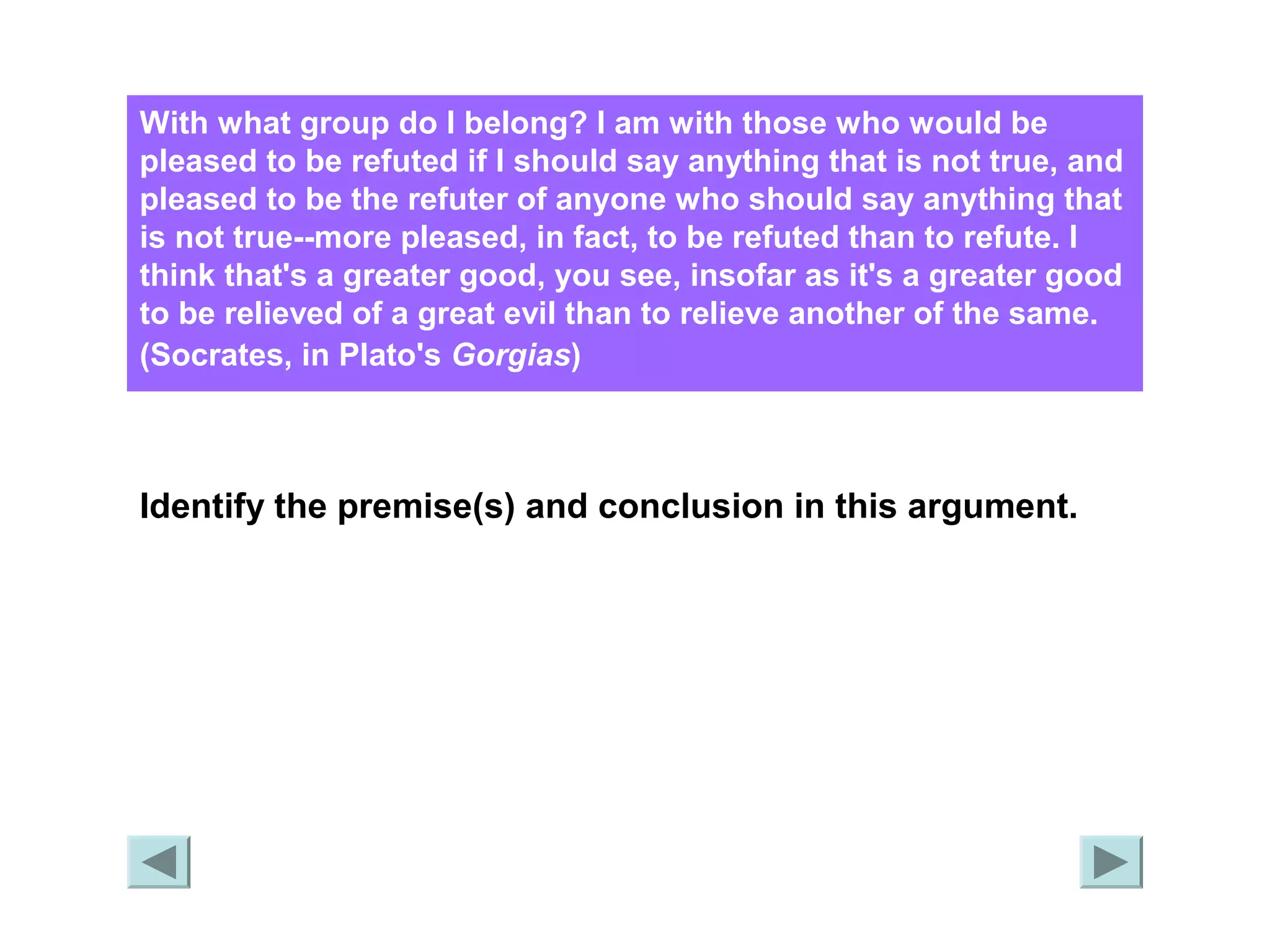

![With what group do I belong? I am with those who would be

pleased to be refuted if I should say anything that is not true, and

pleased to be the refuter of anyone who should say anything that

is not true--more pleased, in fact, to be refuted than to refute. I

think that's a greater good, you see, insofar as it's a greater good

to be relieved of a great evil than to relieve another of the same.

(Socrates, in Plato's Gorgias)

Premise: It is a greater good to be relieved of a great evil than to

relieve another of the same.

Conclusion: It is a greater good to be refuted than to refute.

In this passage, the premise indicator "insofar as" helps us to

identify the premise.

Notice that the first two sentences aren't strictly part of the

argument. Their function, instead, is to provide background or

contextual information necessary to understand the argument.

[This is the end of the tutorial] X](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/premisesandconclusions-140923223853-phpapp01/75/Premises-and-Conclusions-21-2048.jpg)