This document provides an overview of oceanography and its subfields:

- Oceanography is the study of the ocean, its surroundings, and life within it, differing from marine biology which focuses more on individual organisms.

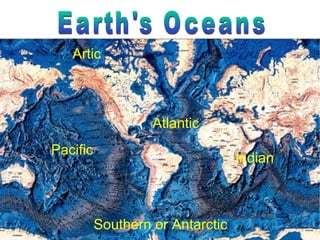

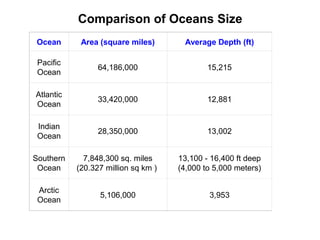

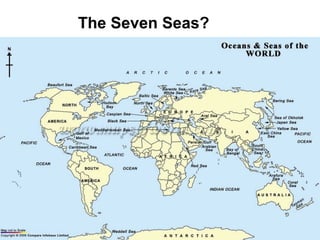

- The five principal oceans are the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Arctic, and Southern oceans.

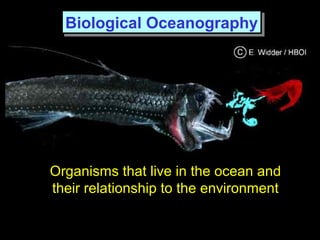

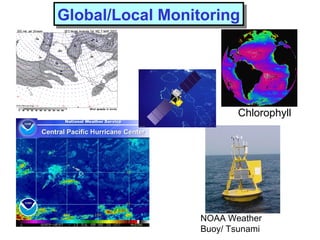

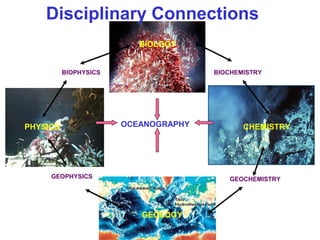

- Oceanography involves the physical, chemical, biological, geological, and engineering aspects of the ocean.

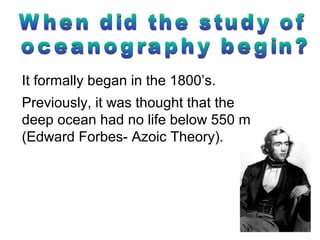

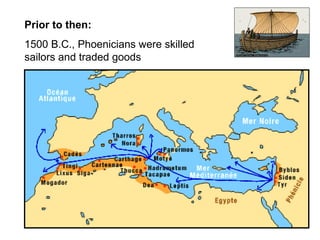

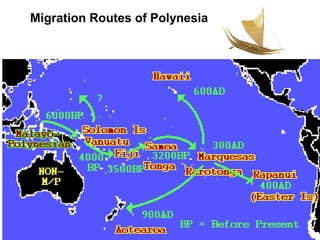

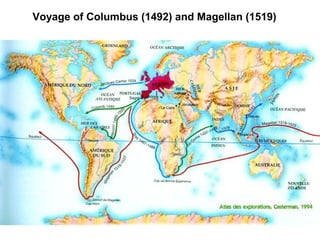

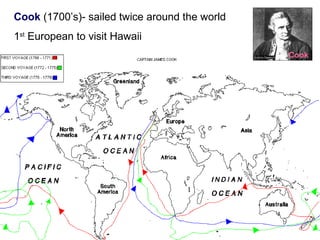

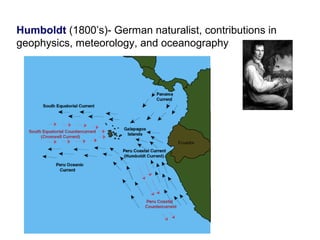

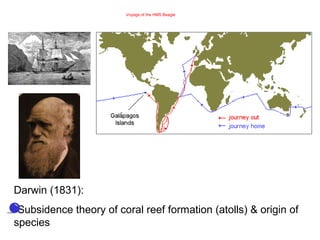

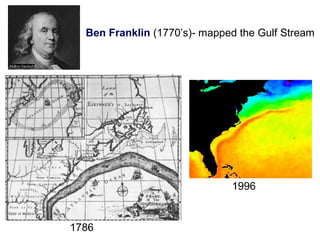

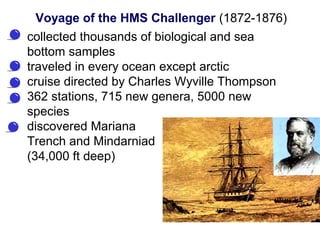

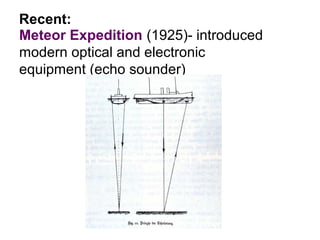

- Important historical figures and voyages helped advance the field, including Darwin, Franklin, the Challenger expedition, and Cousteau.