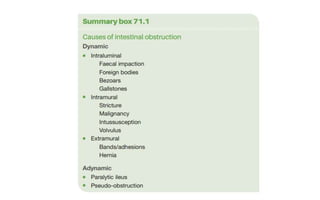

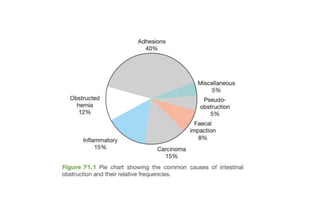

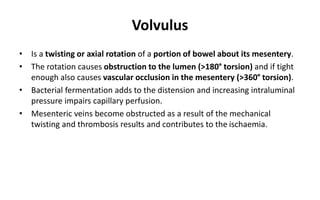

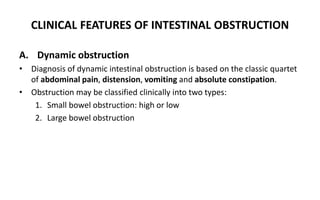

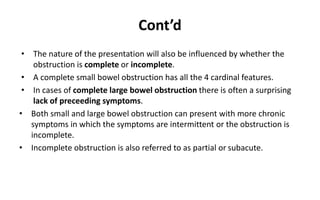

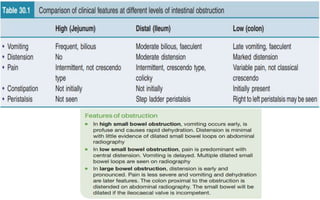

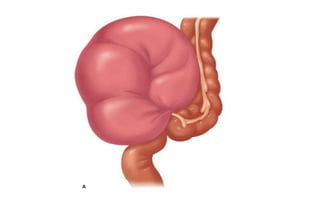

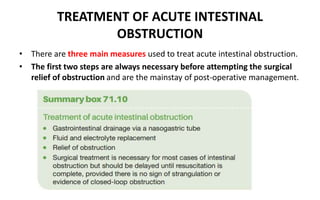

1. Intestinal obstruction occurs when the intestine is blocked, which can be caused by adhesions, hernias, tumors, gallstones, or volvulus. It presents with abdominal pain, distension, vomiting, and constipation.

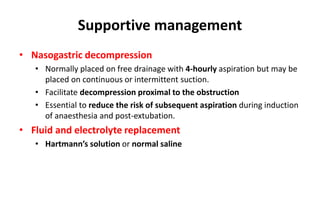

2. Prolonged obstruction leads to dilation of the intestine above the blockage. Fluid and gas accumulate, and the intestine may become ischemic if blood flow is compromised. Dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities can develop.

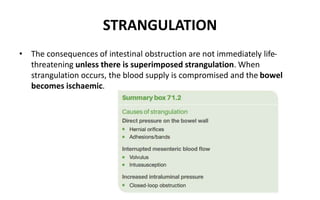

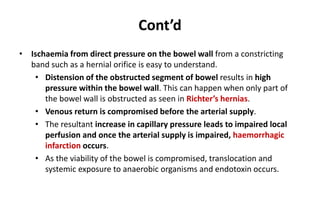

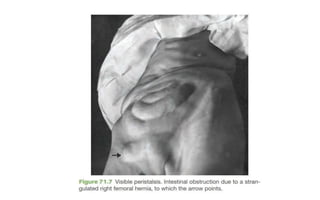

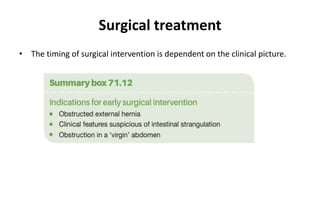

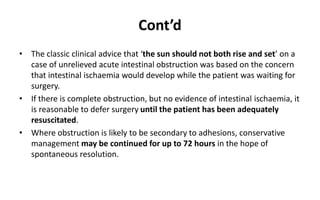

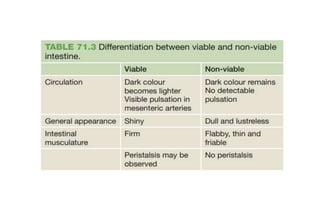

3. Strangulation occurs when the blood supply to the intestine is cut off, which can lead to tissue death. Early diagnosis and treatment are important to prevent complications from ischemia.