SAQIB IMRAN 0341-7549889 11

1. The document is notes written by Saqib Imran, a civil engineering student in Pakistan, to provide knowledge on hydraulic structures to other students and engineers.

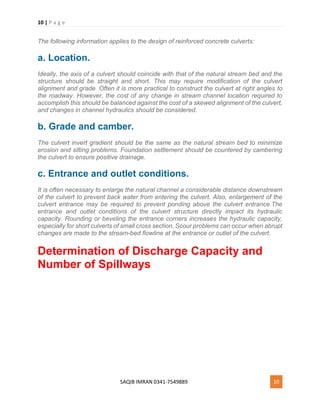

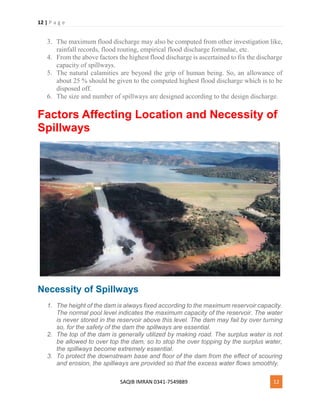

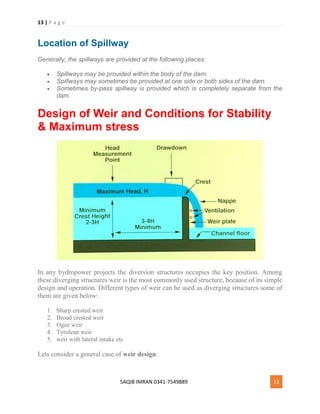

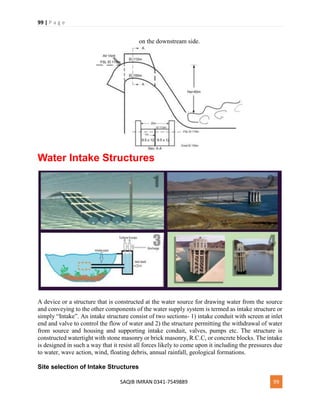

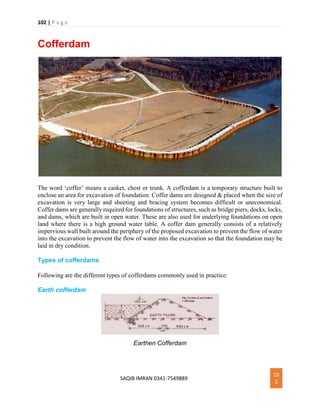

2. It defines hydraulic structures as anything used to divert, restrict, or manage natural water flow, such as dams, weirs, and spillways. It also discusses factors that affect the design of canals, barrages, and culverts.

3. The notes provide definitions for various technical terms related to hydraulic structures like khadir, weir axis, river axis, and retrogression. It also describes river training works including guide banks and marginal bund