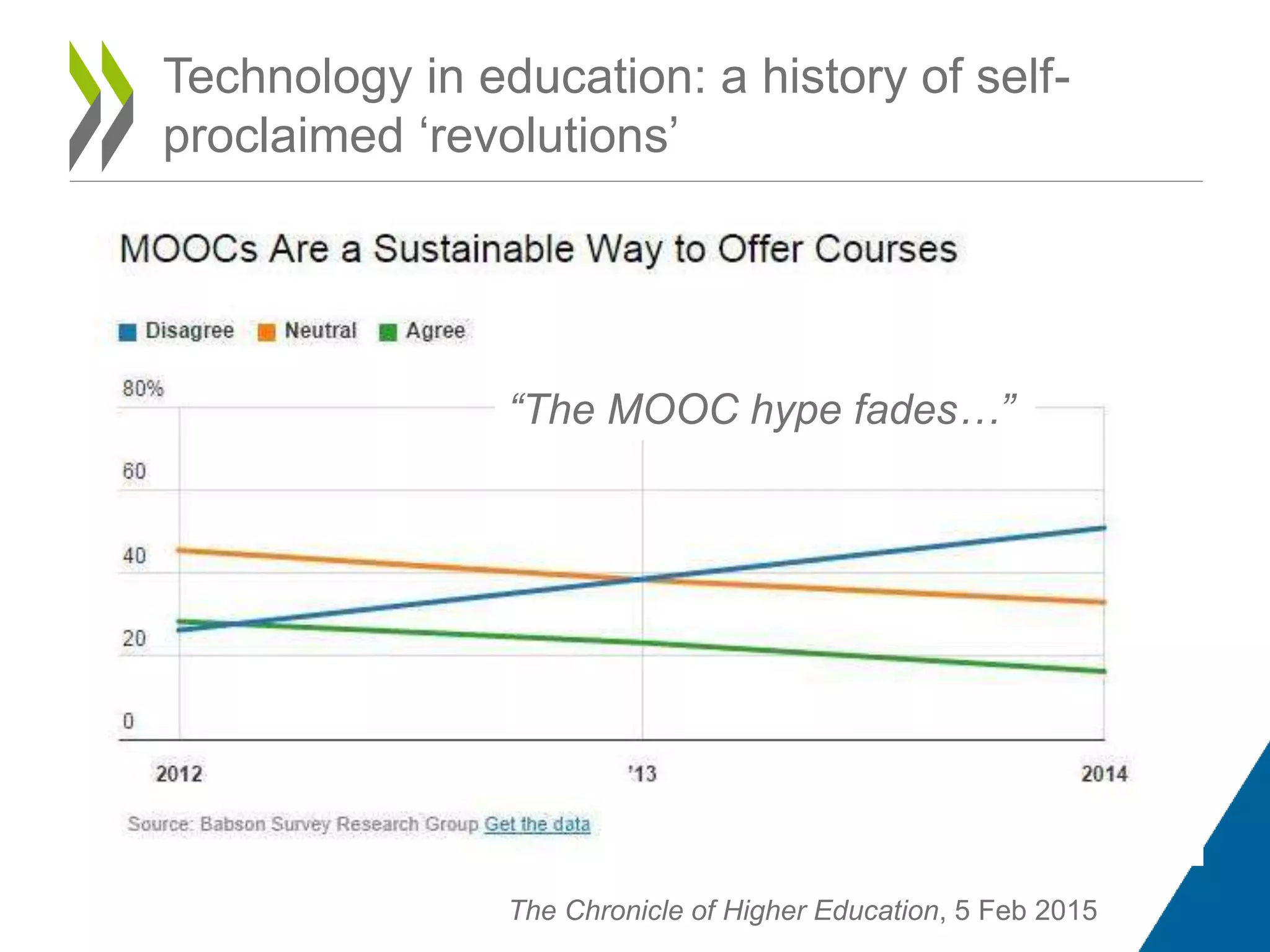

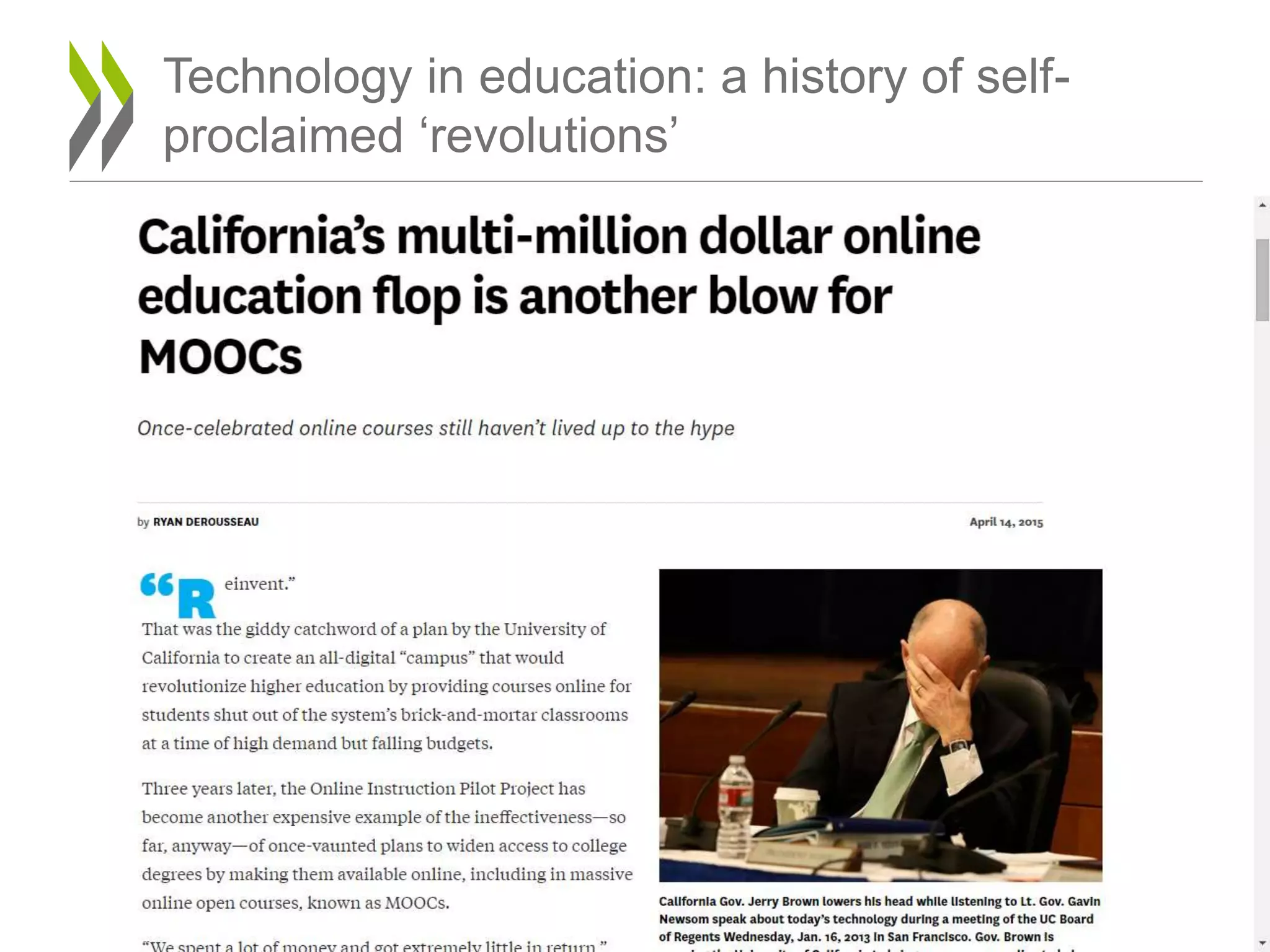

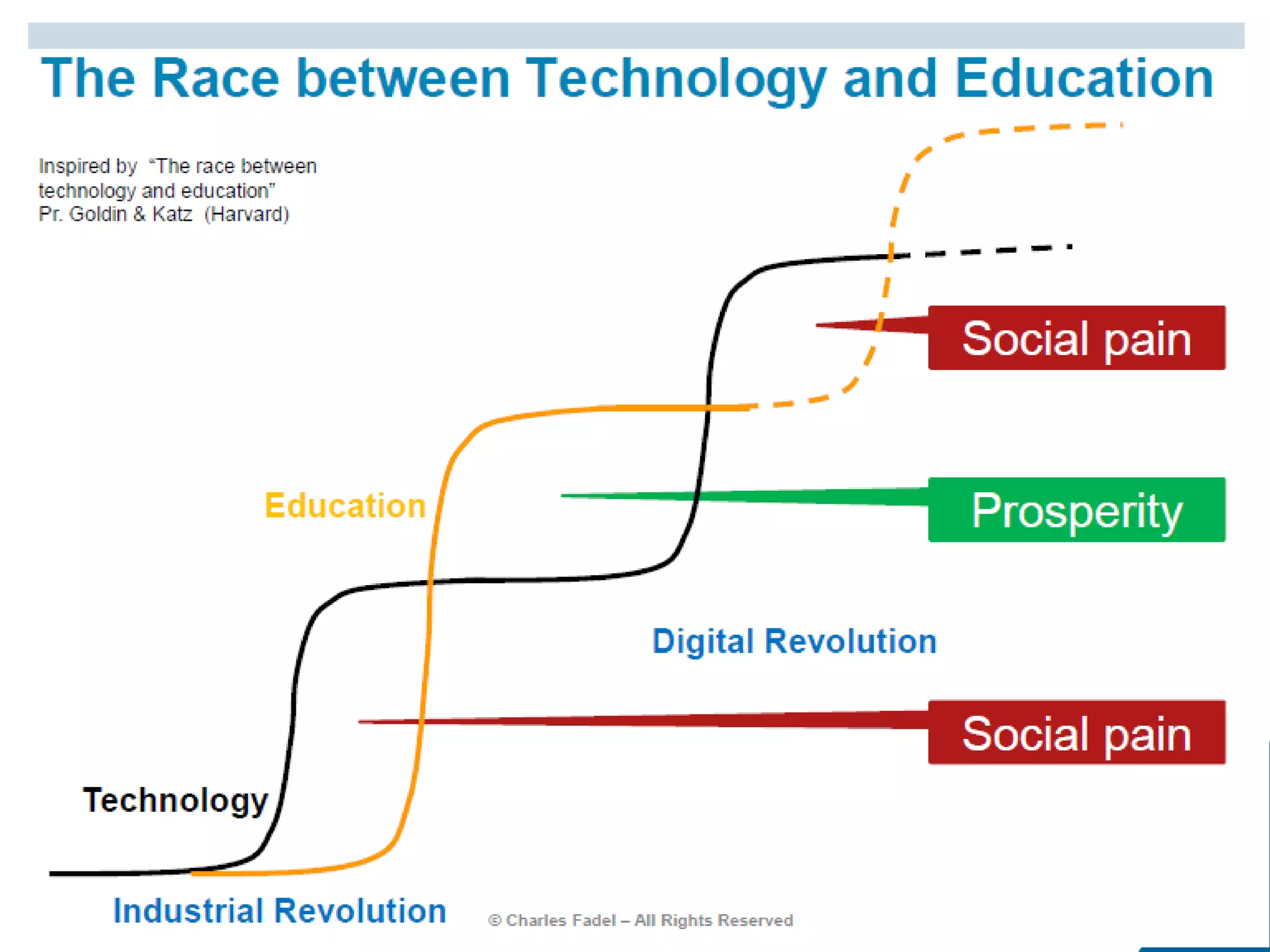

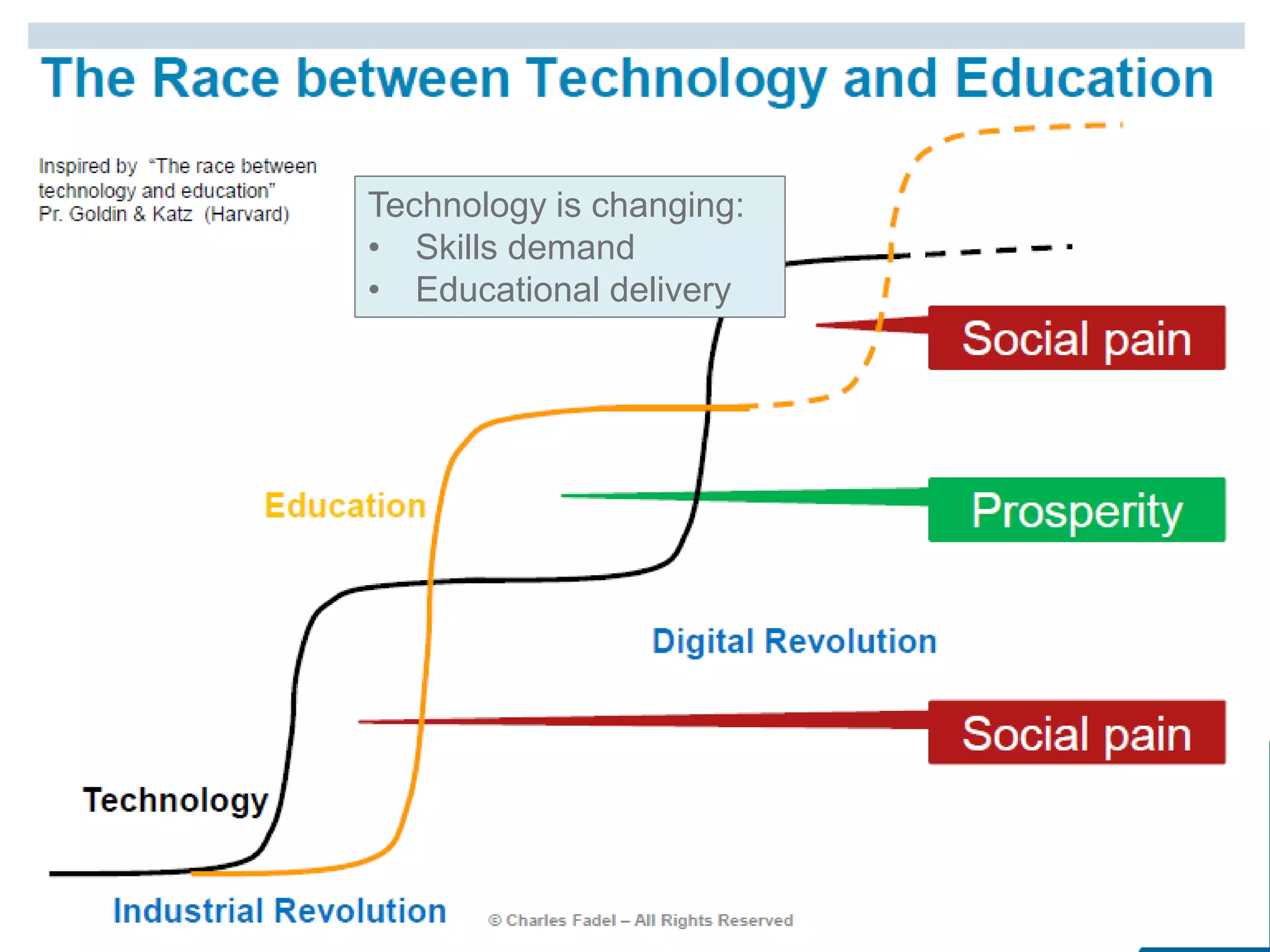

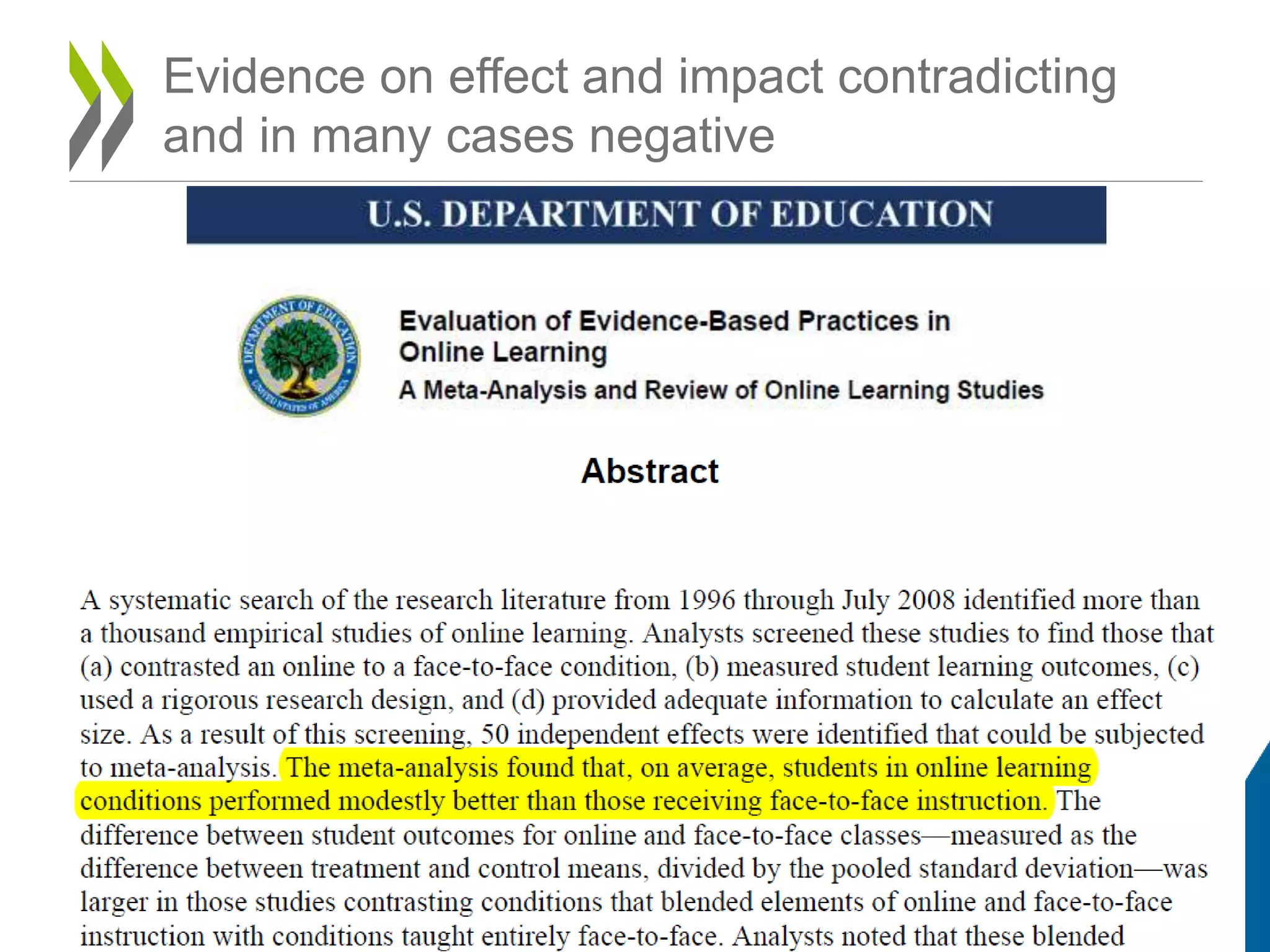

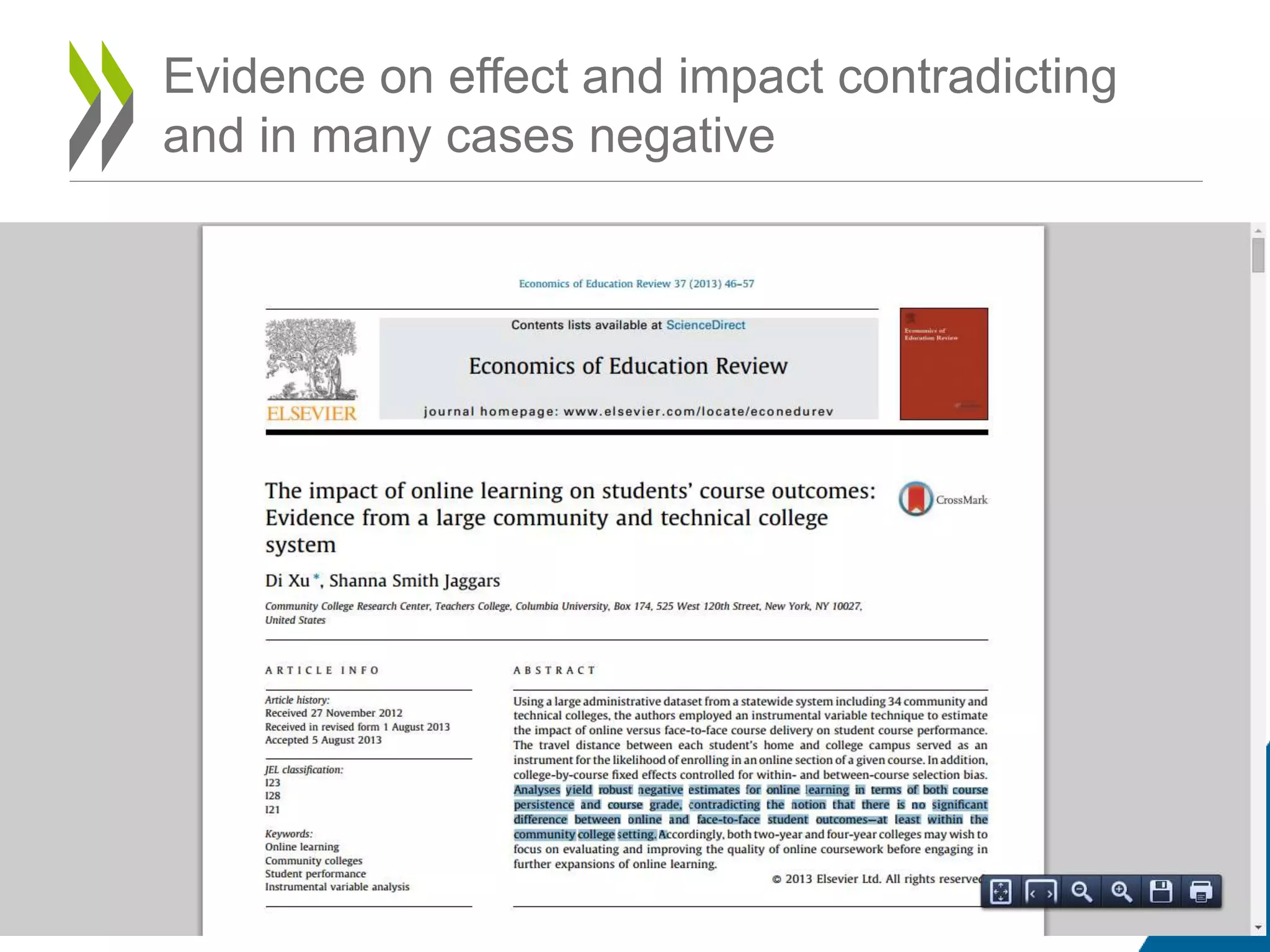

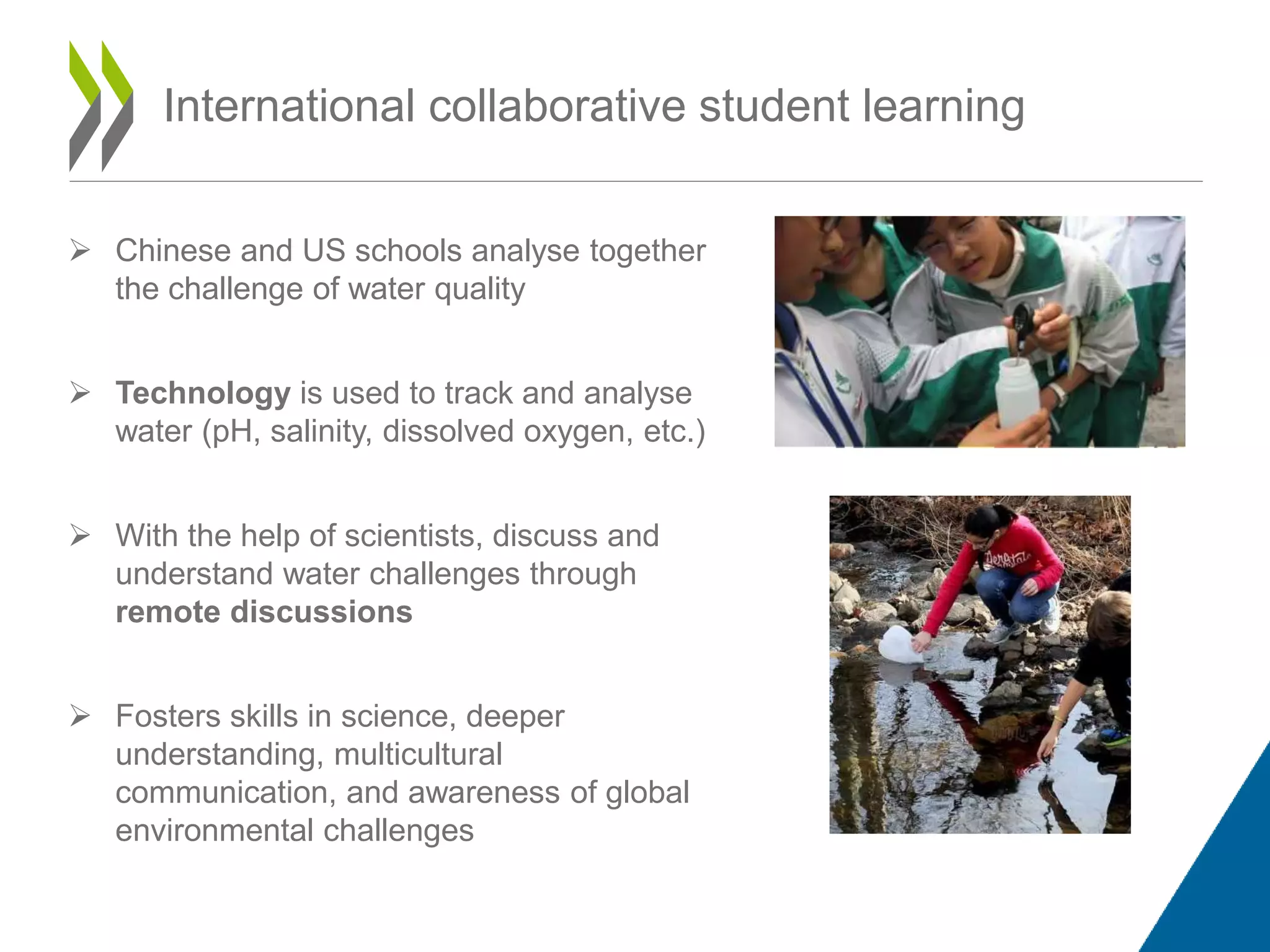

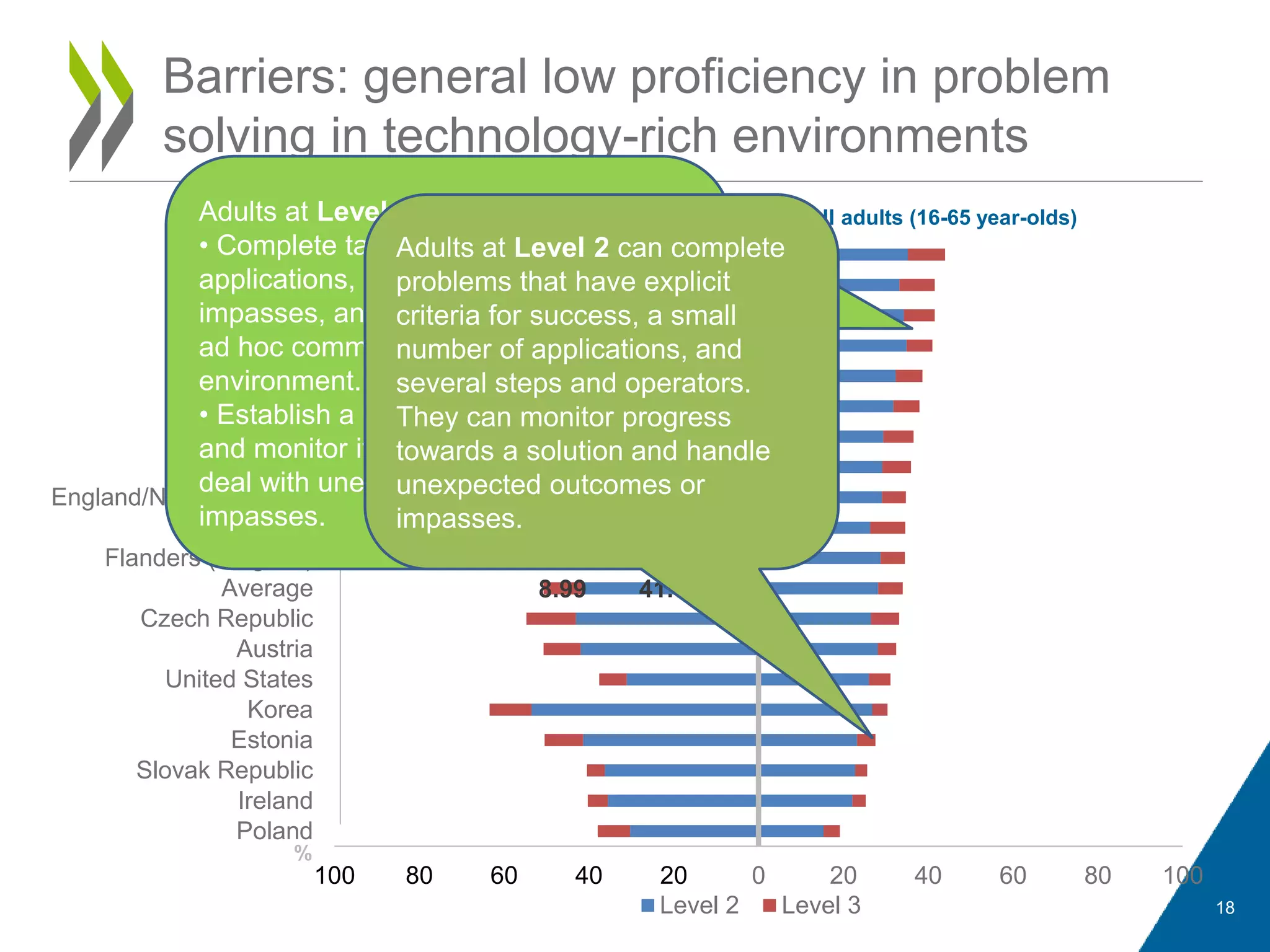

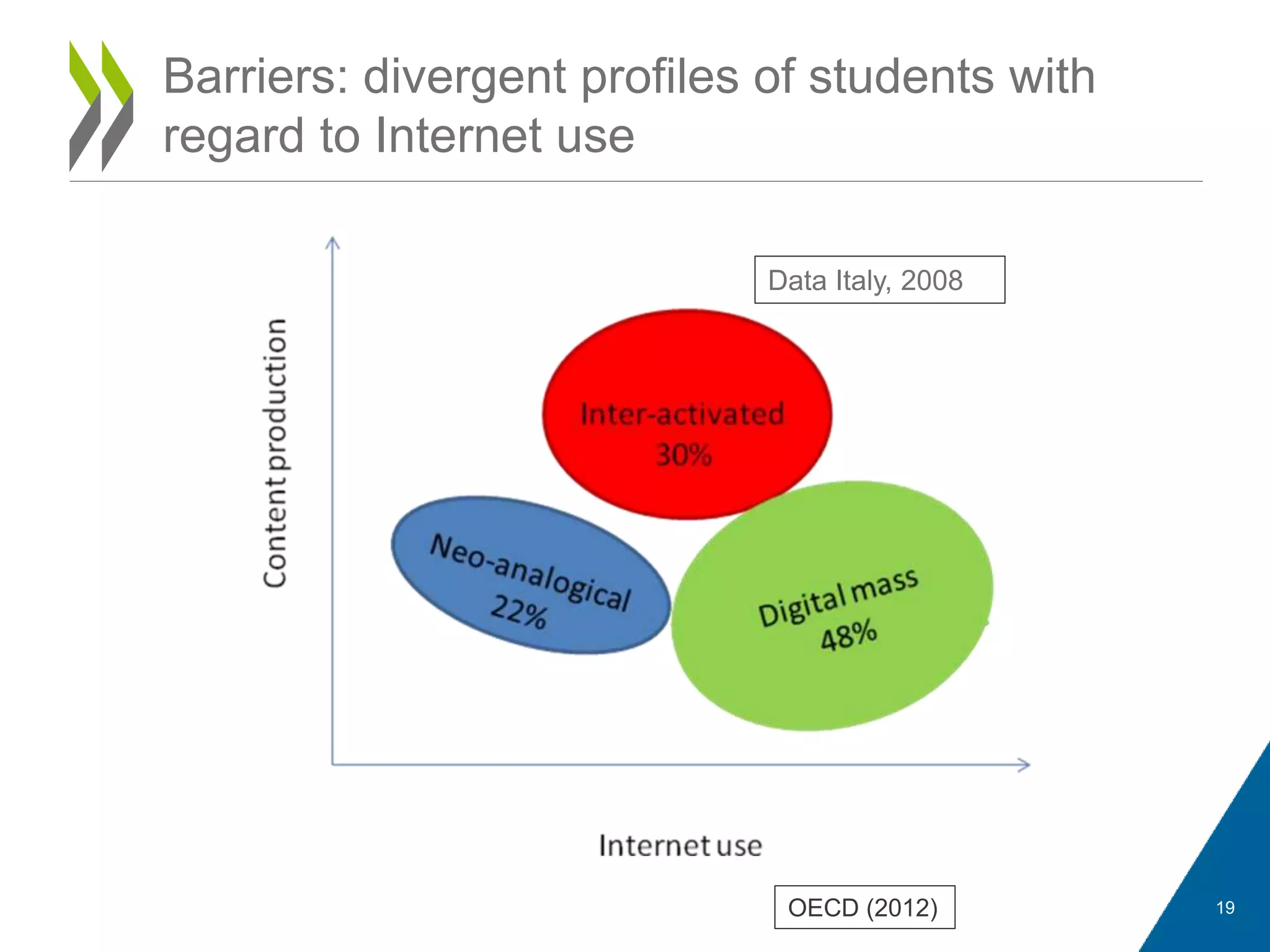

This document discusses how technology can change the way we learn and teach. It explores how technology is impacting skills demand and educational delivery. While technology has been touted as revolutionizing education, evidence on its impact is mixed. The document outlines some promising ways technology could enhance education, such as expanding access to content, supporting new collaborative pedagogies, and providing faster feedback. However, barriers like teachers' and students' limited digital skills and the personal nature of education limit productivity gains from technology. More interactive courseware and social learning tools show potential if developed with strong instructional design.