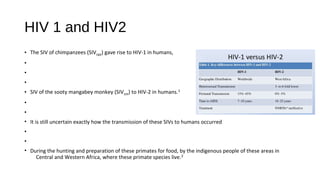

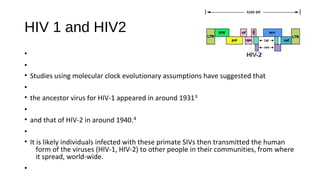

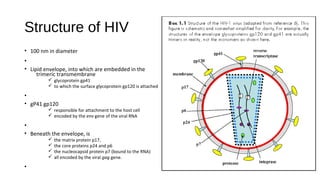

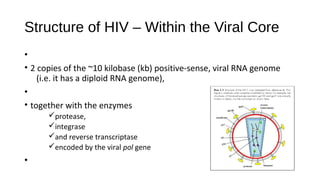

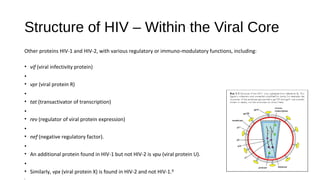

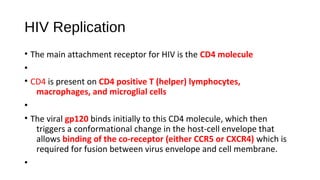

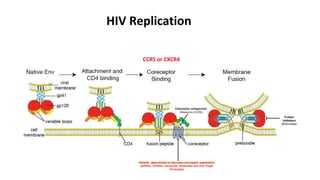

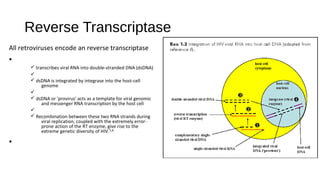

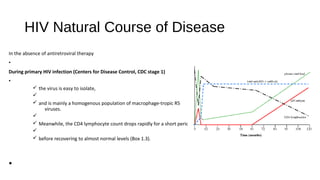

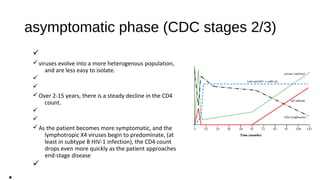

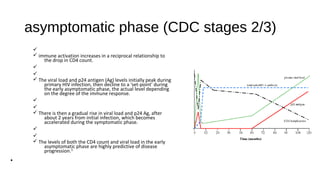

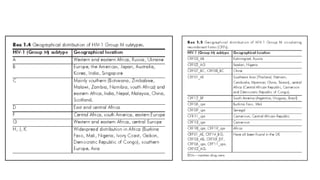

HIV-1 and HIV-2 are zoonotic viruses that originated from primate-derived simian immunodeficiency viruses and have led to significant global epidemics since their isolation in the 1980s. The viruses exhibit substantial genetic diversity, with HIV-1 classified into multiple groups and subtypes, which complicates treatment and vaccine development. The document details the structure, replication process, and natural history of HIV, highlighting the factors affecting disease progression and the global distribution of various HIV subtypes.