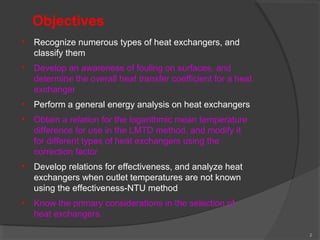

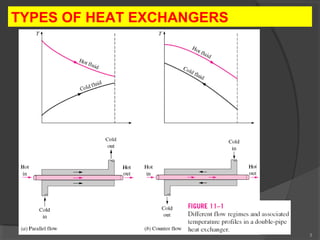

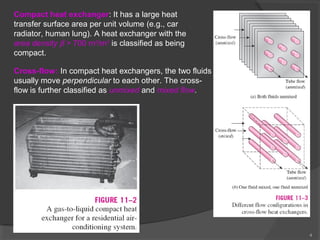

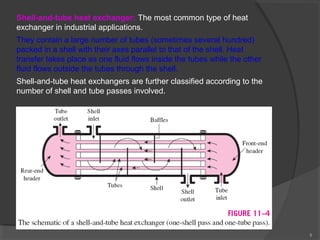

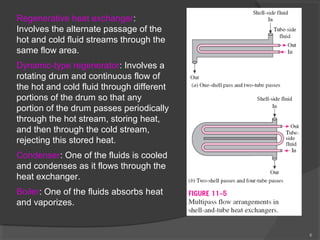

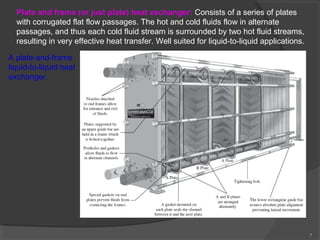

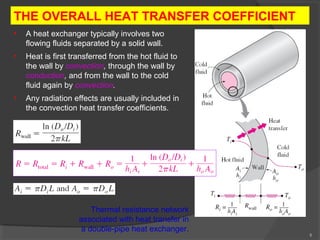

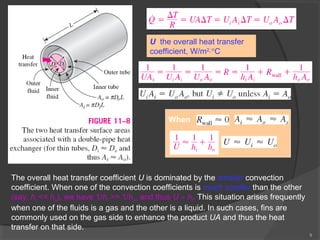

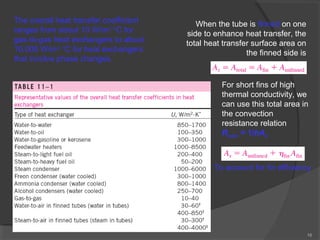

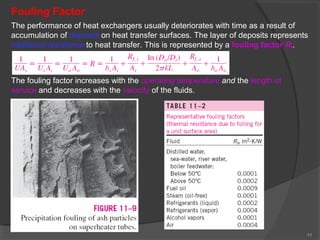

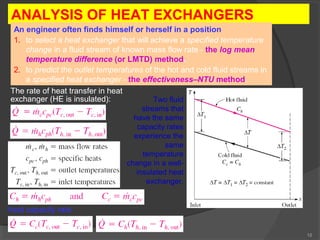

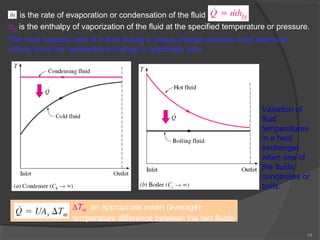

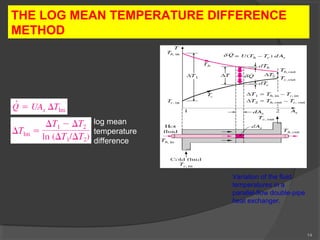

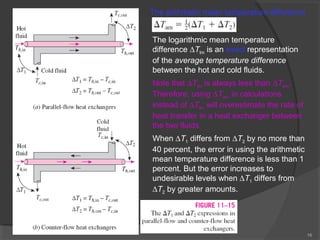

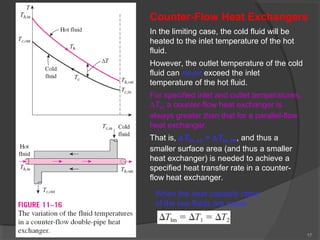

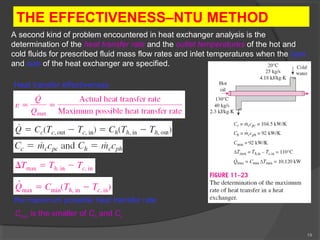

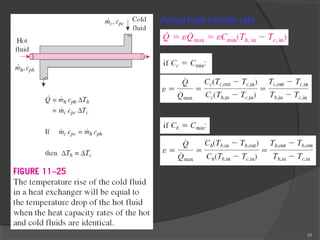

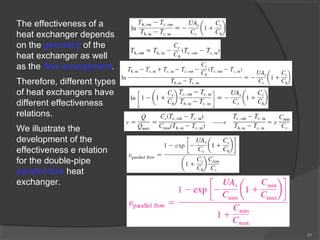

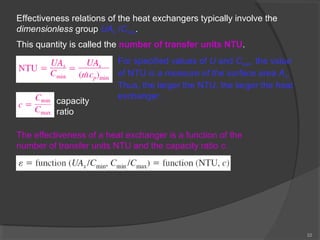

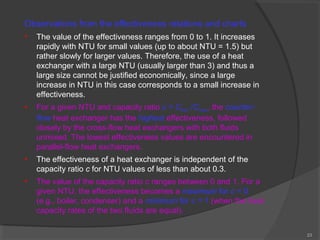

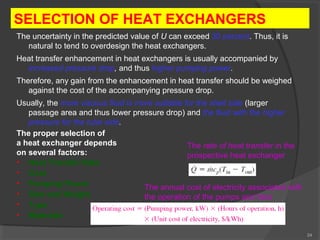

This document discusses heat exchangers and their analysis. It begins by listing the objectives of classifying heat exchangers, determining heat transfer coefficients, and analyzing heat exchangers using effectiveness-NTU and LMTD methods. Several types of heat exchangers are then described, including compact, shell-and-tube, regenerative, plate-frame, and condensers/boilers. Methods for determining overall heat transfer coefficient and fouling factors are provided. The document concludes by explaining the LMTD and effectiveness-NTU methods for analyzing heat exchangers.