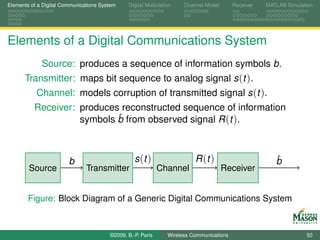

This document provides an outline for a course on modeling wireless communication systems using MATLAB. The course aims to cover both theoretical concepts and practical simulations. MATLAB will be used to illustrate key concepts and visualize signals. Students will learn the basics of MATLAB, including how to represent signals as vectors, perform vector operations, and use built-in functions to manipulate signals. Both theory and MATLAB simulations will be presented in parallel to make concepts concrete.

![User Interface Working with Vectors Visualization

Commands for Creating Vectors

The following commands all create useful vectors.

[ ]: the sequence of samples is explicitly specified.

Example: xx = [ 1 3 2 ] produces xx = 1 3 2.

:(colon operator): creates a vector of equally spaced

samples.

Example: tt = 0:2:9 produces tt = 0 2 4 6 8.

Example: tt = 1:3 produces tt = 1 2 3.

Idiom: tt = ts:1/fs:te creates a vector of sampling times

between ts and te with sampling period 1/fs (i.e., the

sampling rate is fs).

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-23-320.jpg)

![User Interface Working with Vectors Visualization

Addition and Subtraction

The standard + and - operators are used to add and

subtract vectors.

One of two conditions must hold for this operation to

succeed.

Both vectors must have exactly the same size.

In this case, corresponding elements in the two vectors are

added and the result is another vector of the same size.

Example: [1 3 2] + 1:3 produces 2 5 5.

A prominent error message indicates when this condition is

violated.

One of the operands is a scalar, i.e., a 1 × 1 (degenerate)

vector.

In this case, each element of the vector has the scalar added

to it.

The result is a vector of the same size as the vector operand.

Example: [1 3 2] + 2 produces 3 5 4.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-26-320.jpg)

![User Interface Working with Vectors Visualization

Element-wise Multiplication and Division

The operators .* and ./ operators multiply or divide two

vectors element by element.

One of two conditions must hold for this operation to

succeed.

Both vectors must have exactly the same size.

In this case, corresponding elements in the two vectors are

multiplied and the result is another vector of the same size.

Example: [1 3 2] .* 1:3 produces 1 6 6.

An error message indicates when this condition is violated.

One of the operands is a scalar.

In this case, each element of the vector is multiplied by the

scalar.

The result is a vector of the same size as the vector operand.

Example: [1 3 2] .* 2 produces 2 6 4.

If one operand is a scalar the ’.’ may be omitted, i.e.,

[1 3 2] * 2 also produces 2 6 4.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-27-320.jpg)

![User Interface Working with Vectors Visualization

Inner Product

The operator * with two vector arguments computes the

inner product (dot product) of the vectors.

Recall the inner product of two vectors is defined as

N

x ·y = ∑ x (n ) · y (n ).

n =1

This implies that the result of the operation is a scalar!

The inner product is a useful and important signal

processing operation.

It is very different from element-wise multiplication.

The second dimension of the first operand must equal the

first dimension of the second operand.

MATLAB error message: Inner matrix dimensions

must agree.

Example: [1 3 2] * (1:3)’ = 13.

The single quote (’) transposes a vector.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-28-320.jpg)

![User Interface Working with Vectors Visualization

Powers

To raise a vector to some power use the .^ operator.

Example: [1 3 2].^2 yields 1 9 4.

The operator ^ exists but is generally not what you need.

Example: [1 3 2]^2 is equivalent to [1 3 2] * [1 3 2]

which produces an error.

Similarly, to use a vector as the exponent for a scalar base

use the .^ operator.

Example: 2.^[1 3 2] yields 2 8 4.

Finally, to raise a vector of bases to a vector of exponents

use the .^ operator.

Example: [1 3 2].^(1:3) yields 1 9 8.

The two vectors must have the same dimensions.

The .^ operator is (nearly) always the right operator.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-29-320.jpg)

![User Interface Working with Vectors Visualization

Accessing Elements of a Vector

Frequently it is necessary to modify or extract a subset of

the elements of a vector.

Accessing a single element of a vector:

Example: Let xx = [1 3 2], change the third element to 4.

Solution: xx(3) = 4; produces xx = 1 3 4.

Single elements are accessed by providing the index of the

element of interest in parentheses.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-33-320.jpg)

![User Interface Working with Vectors Visualization

Accessing Elements of a Vector

Accessing a range of elements of a vector:

Example: Let xx = ones(1,10);, change the first five

elements to −1.

Solution: xx(1:5) = -1*ones(1,5); Note, xx(1:5) = -1

works as well.

Example: Change every other element of xx to 2.

Solution: xx(2:2:end) = 2;;

Note that end may be use to denote the index of a vector’s

last element.

This is handy if the length of the vector is not known.

Example: Change third and seventh element to 3.

Solution: xx([3 7]) = 3;;

A set of elements of a vector is accessed by providing a

vector of indices in parentheses.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-34-320.jpg)

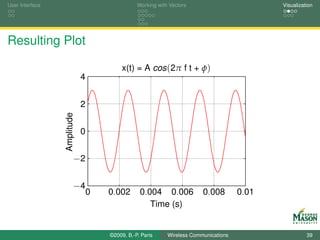

![User Interface Working with Vectors Visualization

A Basic Plot

The sinusoidal signal, we generated earlier is easily plotted

via the following sequence of commands:

Try help plot for more information about the capabilities of

the plot command.

%% Plot

plot(tt, xx, ’r’) % xy-plot, specify red line

xlabel( ’Time (s)’ ) % labels for x and y axis

ylabel( ’Amplitude’ )

10 title( ’x(t) = A cos(2pi f t + phi)’)

grid % create a grid

axis([0 10e-3 -4 4]) % tweak the range for the axes

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-38-320.jpg)

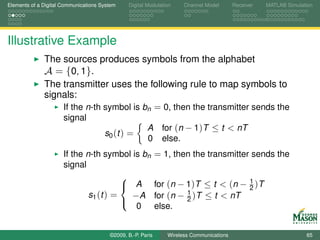

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Modeling the Source in MATLAB

Objective: Write a MATLAB function to be invoked as:

Symbols = RandomSymbols( N, Alphabet, Priors);

The input parameters are

N: number of input symbols to be produced.

Alphabet: source alphabet to draw symbols from.

Example: Alphabet = [1 -1];

Priors: a priori probabilities for the input symbols.

Example:

Priors = ones(size(Alphabet))/length(Alphabet);

The output Symbols is a vector

with N elements,

drawn from Alphabet, and

the number of times each symbol occurs is (approximately)

proportional to the corresponding element in Priors.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-55-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Reminders

MATLAB’s basic data units are vectors and matrices.

Vectors are best thought of as lists of numbers; vectors

often contain samples of a signal.

There are many ways to create vectors, including

Explicitly: Alphabet = [1 -1];

Colon operator: nn = 1:10;

Via a function: Priors=ones(1,5)/5;

This leads to very concise programs; for-loops are rarely

needed.

MATLAB has a very large number of available functions.

Reduces programming to combining existing building

blocks.

Difficulty: find out what is available; use built-in help.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 56](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-56-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Writing a MATLAB Function

A MATLAB function must

begin with a line of the form

function [out1,out2] = FunctionName(in1, in2, in3)

be stored in a file with the same name as the function name

and extension ’.m’.

For our symbol generator, the file name must be

RandomSymbols.m and

the first line must be

function Symbols = RandomSymbols(N, Alphabet, Priors)

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 57](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-57-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Algorithm for Generating Random Symbols

For each of the symbols to be generated we use the

following algorithm:

Begin by computing the cumulative sum over the priors.

Example: Let Priors = [0.25 0.25 0.5], then the

cumulative sum equals CPriors = [0 0.25 0.5 1].

For each symbol, generate a uniform random number

between zero and one.

The MATLAB function rand does that.

Determine between which elements of the cumulative sum

the random number falls and select the corresponding

symbol from the alphabet.

Example: Assume the random number generated is 0.3.

This number falls between the second and third element of

CPriors.

The second symbol from the alphabet is selected.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 60](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-60-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

MATLAB Implementation

In MATLAB, the above algorithm can be “vectorized” to

work on the entire sequence at once.

CPriors = [0 cumsum( Priors )];

rr = rand(1, N);

for kk=1:length(Alphabet)

42 Matches = rr > CPriors(kk) & rr <= CPriors(kk+1);

Symbols( Matches ) = Alphabet( kk );

end

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 61](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-61-320.jpg)

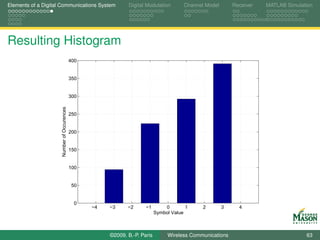

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Testing Function RandomSymols

We can invoke and test the function RandomSymbols as

shown below.

A histogram of the generated symbols should reflect the

specified a priori probabilities.

%% set parameters

N = 1000;

Alphabet = [-3 -1 1 3];

Priors = [0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4];

10

%% generate symbols and plot histogram

Symbols = RandomSymbols( N, Alphabet, Priors );

hist(Symbols, -4:4 );

grid

15 xlabel(’Symbol Value’)

ylabel(’Number of Occurences’)

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 62](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-62-320.jpg)

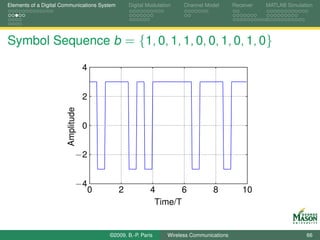

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

MATLAB Code for Example

Listing : plot_TxExampleOrth.m

b = [ 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 0]; %symbol sequence

fsT = 20; % samples per symbol period

A = 3;

6

Signals = A*[ ones(1,fsT); % signals, one per row

ones(1,fsT/2) -ones(1,fsT/2)];

tt = 0:1/fsT:length(b)-1/fsT; % time axis for plotting

11

%% generate signal ...

TXSignal = [];

for kk=1:length(b)

TXSignal = [ TXSignal Signals( b(kk)+1, : ) ];

16 end

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 67](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-67-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

MATLAB Code for Example

Listing : plot_TxExampleOrth.m

%% ... and plot

plot(tt, TXSignal)

20 axis([0 length(b) -(A+1) (A+1)]);

grid

xlabel(’Time/T’)

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 68](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-68-320.jpg)

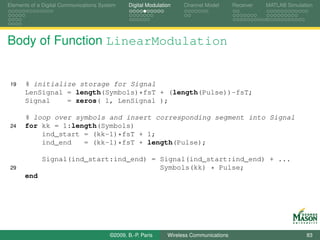

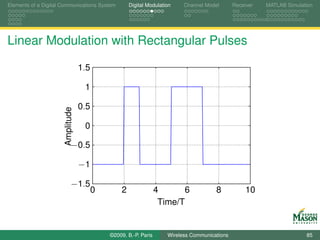

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Testing Function LinearModulation

Listing : plot_LinearModRect.m

%% Parameters:

fsT = 20;

Alphabet = [1,-1];

6 Priors = 0.5*[1 1];

Pulse = ones(1,fsT); % rectangular pulse

%% symbols and Signal using our functions

Symbols = RandomSymbols(10, Alphabet, Priors);

11 Signal = LinearModulation(Symbols,Pulse,fsT);

%% plot

tt = (0 : length(Signal)-1 )/fsT;

plot(tt, Signal)

axis([0 length(Signal)/fsT -1.5 1.5])

16 grid

xlabel(’Time/T’)

ylabel(’Amplitude’)

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 84](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-84-320.jpg)

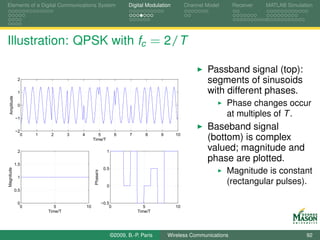

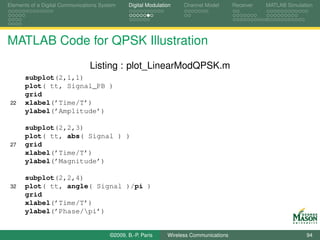

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

MATLAB Code for QPSK Illustration

Listing : plot_LinearModQPSK.m

%% Parameters:

fsT = 20;

L = 10;

fc = 2; % carrier frequency

7 Alphabet = [1, j, -j, -1];% QPSK

Priors = 0.25*[1 1 1 1];

Pulse = ones(1,fsT); % rectangular pulse

%% symbols and Signal using our functions

12 Symbols = RandomSymbols(10, Alphabet, Priors);

Signal = LinearModulation(Symbols,Pulse,fsT);

%% passband signal

tt = (0 : length(Signal)-1 )/fsT;

Signal_PB = sqrt(2)*real( Signal .* exp(-j*2*pi*fc*tt) );

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 93](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-93-320.jpg)

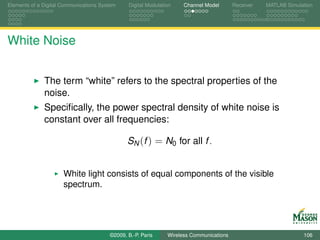

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

White Noise

The term white means specifically that

the mean of the noise is zero,

E[N (t )] = 0,

the autocorrelation function of the noise is

ρN (τ ) = E[N (t ) · N ∗ (t + τ )] = N0 δ(τ ).

This means that any distinct noise samples are

independent.

The autocorrelation function also indicates that noise

samples have infinite variance.

Insight: noise must be filtered before it can be sampled.

In-phase and quadrature noise each have autocorrelation

N0

2 δ ( τ ).

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 105](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-105-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Analog Front-end

Several, roughly equivalent, alternatives exist for the

analog front-end.

Two common approaches for the analog front-end will be

considered briefly.

Primarily, the analog front-end is responsible for converting

the continuous-time received signal R (t ) into a

discrete-time signal R [n].

Care must be taken with the conversion: (ideal) sampling

would admit too much noise.

Modeling the front-end faithfully is important for accurate

simulation.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 118](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-118-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Analog Front-end: Low-pass and Whitening Filter

The first structure contains

a low-pass filter (LPF) with bandwidth equal to the signal

bandwidth,

a sampler followed by a whitening filter (WF).

The low-pass filter creates correlated noise,

the whitening filter removes this correlation.

Sampler,

rate fs

R (t ) R [n] to

LPF WF

DSP

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 119](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-119-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Analog Front-end: Integrate-and-Dump

An alternative front-end has the structure shown below.

Here, ΠTs (t ) indicates a filter with an impulse response that

is a rectangular pulse of length Ts = 1/fs and amplitude

1/Ts .

The entire system is often called an integrate-and-dump

sampler.

Most analog-to-digital converters (ADC) operate like this.

A whitening filter is not required since noise samples are

uncorrelated.

Sampler,

rate fs

R (t ) R [n ] to

ΠTs (t )

DSP

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 120](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-120-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Output from Analog Front-end

The second of the analog front-ends is simpler

conceptually and widely used in practice;

it will be assumed for the remainder of the course.

For simulation purposes, we need to characterize the

output from the front-end.

To begin, assume that the received signal R (t ) consists of

a deterministic signal s (t ) and (AWGN) noise N (t ):

R (t ) = s (t ) + N (t ).

The signal R [n] is a discrete-time signal.

The front-end generates one sample every Ts seconds.

The discrete-time signal R [n] also consists of signal and

noise

R [n ] = s [n ] + N [n ].

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 121](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-121-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Output from Analog Front-end

Consider the signal and noise component of the front-end

output separately.

This can be done because the front-end is linear.

The n-th sample of the signal component is given by:

1 (n+1)Ts

s [n ] = · s (t ) dt ≈ s ((n + 1/2)Ts ).

Ts nTs

The approximation is valid if fs = 1/Ts is much greater than

the signal band-width.

Sampler,

rate fs

R (t ) R [n ] to

ΠTs (t )

DSP

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 122](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-122-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Output from Analog Front-end

The noise samples N [n] at the output of the front-end:

are independent, complex Gaussian random variables, with

zero mean, and

variance equal to N0 /Ts .

The variance of the noise samples is proportional to 1/Ts .

Interpretations:

Noise is averaged over Ts seconds: variance decreases with

length of averager.

Bandwidth of front-end filter is approximately 1/Ts and

power of filtered noise is proportional to bandwidth (noise

bandwidth).

It will be convenient to express the noise variance as

N0 /T · T /Ts .

The factor T /Ts = fs T is the number of samples per

symbol period.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 123](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-123-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

System to be Simulated

Sampler,

N (t )

rate fs

bn s (t ) R (t ) R [n] to

× p (t ) × h (t ) + ΠTs (t )

DSP

∑ δ(t − nT ) A

Figure: Baseband Equivalent System to be Simulated.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-136-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Towards the Discrete-Time Equivalent System

The shaded portion of the system has a discrete-time input

and a discrete-time output.

Can be considered as a discrete-time system.

Minor problem: input and output operate at different rates.

Sampler,

N (t )

rate fs

bn s (t ) R (t ) R [n] to

× p (t ) × h (t ) + ΠTs (t )

DSP

∑ δ(t − nT ) A

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 138](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-138-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Discrete-Time Equivalent System

The discrete-time equivalent system

is equivalent to the original system, and

contains only discrete-time signals and components.

Input signal is up-sampled by factor fs T to make input and

output rates equal.

Insert fs T − 1 zeros between input samples.

N [n ]

bn R [n ]

× ↑ fs T h [n ] + to DSP

A

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 139](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-139-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Components of Discrete-Time Equivalent System

Question: What is the relationship between the

components of the original and discrete-time equivalent

system?

Sampler,

N (t )

rate fs

bn s (t ) R (t ) R [n] to

× p (t ) × h (t ) + ΠTs (t )

DSP

∑ δ(t − nT ) A

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 140](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-140-320.jpg)

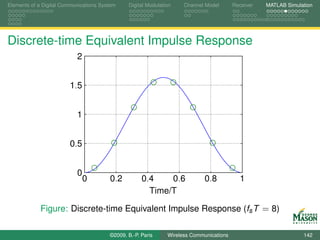

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Discrete-time Equivalent Impulse Response

To determine the impulse response h[n] of the

discrete-time equivalent system:

Set noise signal Nt to zero,

set input signal bn to unit impulse signal δ[n],

output signal is impulse response h[n].

Procedure yields:

1 ( n + 1 ) Ts

h [n ] = p (t ) ∗ h(t ) dt

Ts nTs

For high sampling rates (fs T 1), the impulse response is

closely approximated by sampling p (t ) ∗ h(t ):

h[n] ≈ p (t ) ∗ h(t )|(n+ 1 )Ts

2

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 141](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-141-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Discrete-Time Equivalent Noise

To determine the properties of the additive noise N [n] in

the discrete-time equivalent system,

Set input signal to zero,

let continuous-time noise be complex, white, Gaussian with

power spectral density N0 ,

output signal is discrete-time equivalent noise.

Procedure yields: The noise samples N [n]

are independent, complex Gaussian random variables, with

zero mean, and

variance equal to N0 /Ts .

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 143](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-143-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Listing : SimpleSetParameters.m

% This script sets a structure named Parameters to be used by

% the system simulator.

%% Parameters

7 % construct structure of parameters to be passed to system simulator

% communications parameters

Parameters.T = 1/10000; % symbol period

Parameters.fsT = 8; % samples per symbol

Parameters.Es = 1; % normalize received symbol energy to 1

12 Parameters.EsOverN0 = 6; % Signal-to-noise ratio (Es/N0)

Parameters.Alphabet = [1 -1]; % BPSK

Parameters.NSymbols = 1000; % number of Symbols

% discrete-time equivalent impulse response (raised cosine pulse)

17 fsT = Parameters.fsT;

tts = ( (0:fsT-1) + 1/2 )/fsT;

Parameters.hh = sqrt(2/3) * ( 1 - cos(2*pi*tts)*sin(pi/fsT)/(pi/fsT));

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 146](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-146-320.jpg)

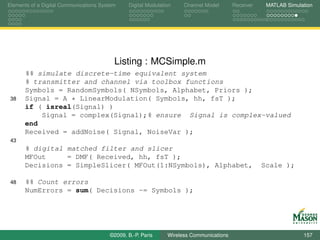

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Simulating the Discrete-Time Equivalent System

The actual system simulation is carried out in MATLAB

function MCSimple which has the function signature below.

The parameters set in the controlling script are passed as

inputs.

The body of the function simulates the transmission of the

signal and subsequent demodulation.

The number of incorrect decisions is determined and

returned.

function [NumErrors, ResultsStruct] = MCSimple( ParametersStruct )

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 147](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-147-320.jpg)

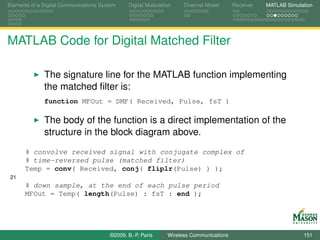

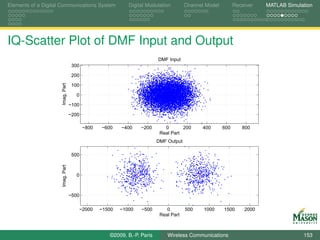

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Digital Matched Filter

In our simulator, the vector Received is passed through a

discrete-time matched filter and down-sampled to the

symbol rate.

The impulse response of the matched filter is the conjugate

complex of the time-reversed, discrete-time channel

response h[n].

R [n ] ˆ

bn

h∗ [−n] ↓ fs T Slicer

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 150](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-150-320.jpg)

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

MATLAB Function SimpleSlicer

The procedure above is implemented in a function with

signature

function [Decisions, MSE] = SimpleSlicer( MFOut, Alphabet, Scale )

%% Loop over symbols to find symbol closest to MF output

for kk = 1:length( Alphabet )

% noise-free signal location

28 NoisefreeSig = Scale*Alphabet(kk);

% Euclidean distance between each observation and constellation po

Dist = abs( MFOut - NoisefreeSig );

% find locations for which distance is smaller than previous best

ChangedDec = ( Dist < MinDist );

33

% store new min distances and update decisions

MinDist( ChangedDec) = Dist( ChangedDec );

Decisions( ChangedDec ) = Alphabet(kk);

end

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 155](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-155-320.jpg)

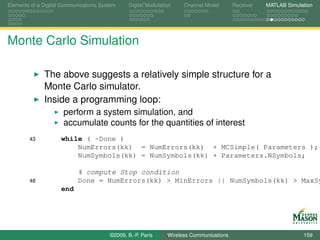

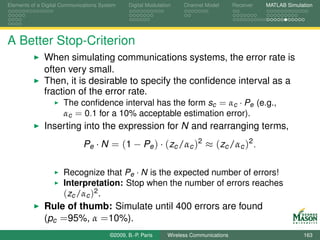

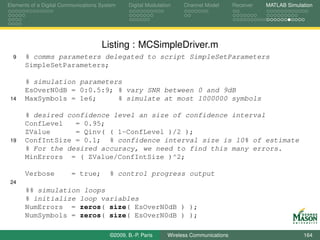

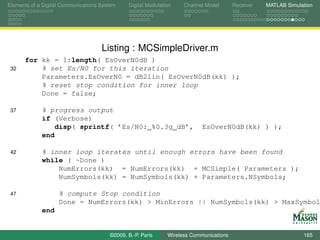

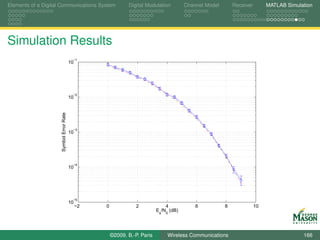

![Elements of a Digital Communications System Digital Modulation Channel Model Receiver MATLAB Simulation

Entire System

The addition of functions for the digital matched filter

completes the simulator for the communication system.

The functionality of the simulator is encapsulated in a

function with signature

function [NumErrors, ResultsStruct] = MCSimple( ParametersStruct )

The function simulates the transmission of a sequence of

symbols and determines how many symbol errors occurred.

The operation of the simulator is controlled via the

parameters passed in the input structure.

The body of the function is shown on the next slide; it

consists mainly of calls to functions in our toolbox.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 156](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-156-320.jpg)

![Linear Modulation Formats and their Spectra Spectrum Estimation in MATLAB Non-linear Modulation Wide-Band Modulation

Toolbox function DPSK

The toolbox function DPSK with the following function

signature provides generic differential phase encoding:

1 function DPSKSymbols = DPSK( PAMSymbols, phi0, theta0 )

The body of DPSK computes differentially encoded

symbols as follows:

%% accumulate phase differences, then convert to complex symbols

Phases = cumsum( [theta0 phi0*PAMSymbols] );

DPSKSymbols = exp( j*Phases );

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 207](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-207-320.jpg)

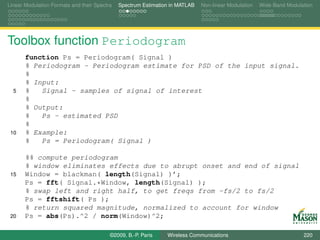

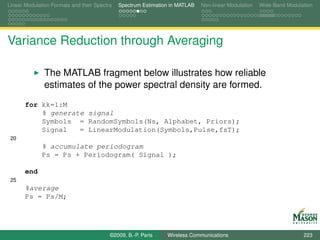

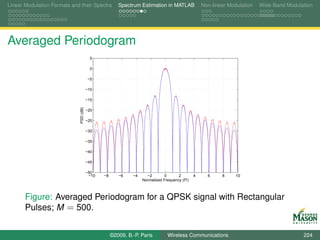

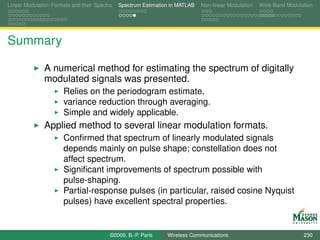

![Linear Modulation Formats and their Spectra Spectrum Estimation in MATLAB Non-linear Modulation Wide-Band Modulation

Improving the Periodogram Estimate

The periodogram estimate is extremely noisy.

ˆ

It is known that the periodogram Ps (f ) has a Gaussian

distribution and

ˆ

is an unbiased estimate E[Ps (f )] = Ps (f ),

ˆ

has variance Var[Ps (f )] = Ps (f ).

The variance of the periodogram is too high for the estimate

to be useful.

Fortunately, the variance is easily reduced through

averaging:

Generate M realizations of the modulated signal, and

average the periodograms for the signals.

Reduces variance by factor M.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 222](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-222-320.jpg)

![Linear Modulation Formats and their Spectra Spectrum Estimation in MATLAB Non-linear Modulation Wide-Band Modulation

Generating CPM Signals in MATLAB

We have enough information to write a toolbox function to

generate CPM signal; it has the signature

function [CPMSignal, PAMSignal] = CPM(Symbols, A, h, Pulse, fsT)

The body of the function

calls LinearModulation to generate the PAM signal,

performs numerical integration through a suitable IIR filter

%% Generate PAM signal, using function LinearModulation

PAMSignal = LinearModulation( Symbols, Pulse, fsT );

%% Integrate PAM signal using a filter with difference equation

30 % y(n) = y(n-1) + x(n)/fsT and multiply with 2*pi*h

a = [1 -1];

b = 1/fsT;

Phase = 2*pi*h*filter(b, a, PAMSignal);

35 %% Baseband equivalent signal

CPMSignal = A*exp(j*Phase);

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 236](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-236-320.jpg)

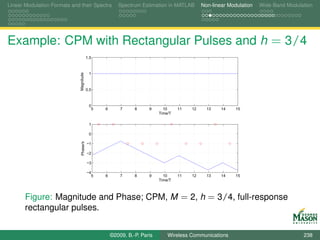

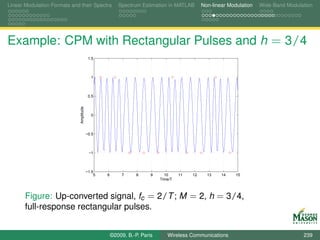

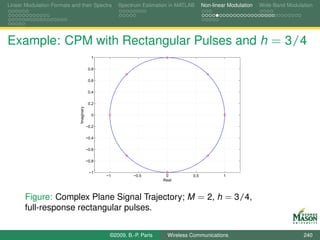

![Linear Modulation Formats and their Spectra Spectrum Estimation in MATLAB Non-linear Modulation Wide-Band Modulation

Using Toolbox Function CPM

A typical invocation of the function CPM is as follows:

%% Parameters:

fsT = 20;

Alphabet = [1,-1]; % 2-PAM

6 Priors = ones( size( Alphabet) ) / length(Alphabet);

Ns = 20; % number of symbols

Pulse = RectPulse( fsT); % Rectangular pulse

A = 1; % amplitude

h = 0.75; % modulation index

11

%% symbols and Signal using our functions

Symbols = RandomSymbols(Ns, Alphabet, Priors);

Signal = CPM(Symbols, A, h, Pulse,fsT);

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 237](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-237-320.jpg)

![Linear Modulation Formats and their Spectra Spectrum Estimation in MATLAB Non-linear Modulation Wide-Band Modulation

Digital Synthesis of a Carrier Modulated Signal

To start, assume we wanted to generate the samples for a

linearly modulated signal:

symbol for the m-th symbol period bm (k ),

N samples per symbol period,

rectangular pulses,

up-conversion to digital frequency k /N (physical frequency

fs · k /N).

The resulting samples in the m-th symbol period are

sm,k [n] = bm (k ) · exp(j2πkn/N ) for n = 0, 1, . . . , N − 1.

If these samples were passed through a D-to-A converter,

we would observe a signal spectrum

centered at frequency fs · k /N, and

bandwidth 2fs /N.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 269](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-269-320.jpg)

![Linear Modulation Formats and their Spectra Spectrum Estimation in MATLAB Non-linear Modulation Wide-Band Modulation

Combining Carriers

The single carrier occupies only a small fraction of the

bandwidth fs the A-to-D converter can process.

The remaining bandwidth can be used for additional

signals.

Specifically, we can combine N such signals.

Carrier frequencies: fs · k /N for k = 0, 1, . . . N − 1.

Resulting carriers are all orthogonal.

Samples of the combined signal in the m-th symbol period

are

N −1 N −1

sm [ n ] = ∑ sm,k [n] = ∑ bm (k ) · exp(j2πkn/N ).

k =0 k =0

The signal sm [n] represents N orthogonal narrow-band

signals multiplexed in the frequency domain (OFDM).

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 270](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-270-320.jpg)

![Linear Modulation Formats and their Spectra Spectrum Estimation in MATLAB Non-linear Modulation Wide-Band Modulation

Constructing an OFDM Signal

The expression

N −1

sm [ n ] = ∑ bm (k ) · exp(j2πkn/N ).

k =0

represents the inverse DFT of the symbols bm (k ).

Direct evaluation of this equation requires N 2

multiplications and additions.

However, the structure of the expression permits

computationally efficient construction of sm [n] through an

FFT algorithm.

MATLAB’s function ifft can be used.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 271](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-271-320.jpg)

![Linear Modulation Formats and their Spectra Spectrum Estimation in MATLAB Non-linear Modulation Wide-Band Modulation

Constructing an OFDM Signal

The above considerations suggest the following procedure

for constructing an OFDM signal from a sequence of

information symbols b:

1. Serial-to-parallel conversion: break the sequence of

information symbols b into blocks of length N;

denote the k -th symbol in the m-th block as bm (k ).

2. Inverse DFT: Take the inverse FFT of each block m;

The output are length-N blocks of complex signal samples

denoted sm [n].

3. Cyclic prefix: Prepend the final L samples from each block

to the beginning of each block.

Cyclic protects against ISI.

4. Parallel-to-serial conversion: Concatenate the blocks to

form the OFDM signal.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 272](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-272-320.jpg)

![Linear Modulation Formats and their Spectra Spectrum Estimation in MATLAB Non-linear Modulation Wide-Band Modulation

Toolbox Function OFDMMod

%% Serial-to-parallel conversion

NBlocks = ceil( length(Symbols) / NCarriers );

% zero-pad, if needed

33 Blocks = zeros( 1, NBlocks*NCarriers );

Blocks(1:length(Symbols)) = Symbols;

% serial-to-parallel

Blocks = reshape( Blocks, NCarriers, NBlocks );

38 %% IFFT

% ifft works column-wise by default

Blocks = ifft( Blocks );

%% cyclic prefix

43 % copy last LPrefix samples of each column and prepend

Blocks = [ Blocks( end-LPrefix+1 : end, : ) ; Blocks ];

%% Parallel-to-serial conversion

Signal = reshape( Blocks, 1, NBlocks*(NCarriers+LPrefix) ) * ...

48 sqrt(NCarriers); % makes "gain" of ifft equal to 1.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 275](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-275-320.jpg)

![Linear Modulation Formats and their Spectra Spectrum Estimation in MATLAB Non-linear Modulation Wide-Band Modulation

Toolbox Function OFDMDemod

%% Serial-to-parallel conversion

32 NBlocks = ceil( length(Signal) / (NCarriers+LPrefix) );

if ( (NCarriers+LPrefix)*NBlocks ~= length(Signal) )

error(’Length of Signal must be a multiple of (NCarriers+LPrefix)’

end

% serial-to-parallel

37 Blocks = reshape( Signal/sqrt(NCarriers), NCarriers+LPrefix, NBlocks )

%% remove cyclic prefix

% remove first LPrefix samples of each column

Blocks( 1:LPrefix, : ) = [ ];

42

%% FFT

% fft works column-wise by default

Blocks = fft( Blocks );

47 %% Parallel-to-serial conversion

SymbolEst = reshape( Blocks, 1, NBlocks*NCarriers );

% remove zero-padding

SymbolEst = SymbolEst(1:NSymbols);

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 276](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-276-320.jpg)

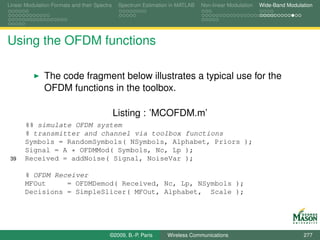

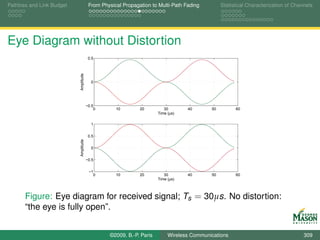

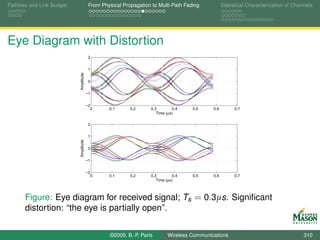

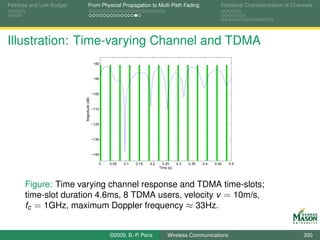

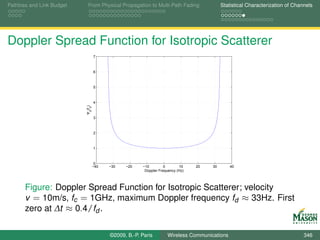

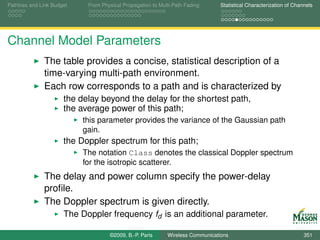

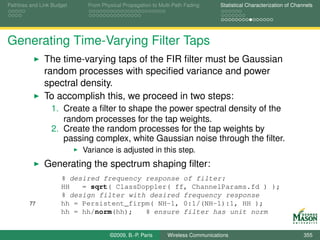

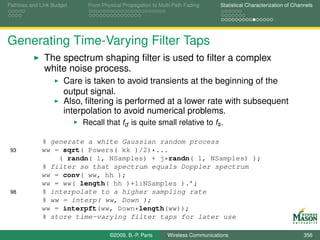

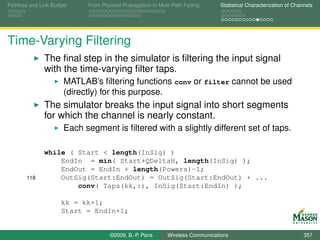

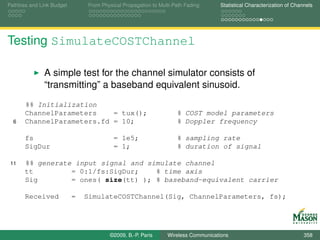

![Pathloss and Link Budget From Physical Propagation to Multi-Path Fading Statistical Characterization of Channels

Eye Diagrams for Visualizing Distortion

An eye diagram is a simple but useful tool for quickly

gaining an appreciation for the amount of distortion present

in a received signal.

An eye diagram is obtained by plotting many segments of

the received signal on top of each other.

The segments span two symbol periods.

This can be accomplished in MATLAB via the command

plot( tt(1:2*fsT), real(reshape(Received(1:Ns*fsT), 2*fsT, [ ])))

Ns - number of symbols; should be large (e.g., 1000),

Received - vector of received samples.

The reshape command turns the vector into a matrix with

2*fsT rows, and

the plot command plots each column of the resulting matrix

individually.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 308](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-308-320.jpg)

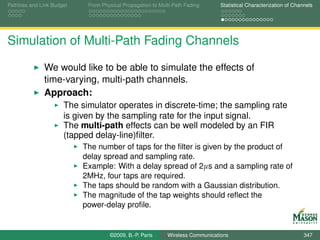

![Pathloss and Link Budget From Physical Propagation to Multi-Path Fading Statistical Characterization of Channels

Simulation of Multi-Path Fading Channels

The taps are modeled as

Gaussian random processes

with variances given by the power delay profile, and

power spectral density given by the Doppler spectrum.

s [n ]

D D

a0 (t ) × a1 ( t ) × a2 (t ) ×

r [n ]

+ +

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 349](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-349-320.jpg)

![The Importance of Diversity Frequency Diversity: Wide-Band Signals

System to be Analyzed

The simple communication system in the diagram below

will be analyzed.

Focus on the effects of the multi-path channel h(t ).

Assumption: low baud rate, i.e., narrow-band signal.

Sampler,

N (t )

rate fs

bn s (t ) R (t ) R [n] to

× p (t ) × h (t ) + ΠTs (t )

DSP

∑ δ(t − nT ) A

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 368](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-368-320.jpg)

![The Importance of Diversity Frequency Diversity: Wide-Band Signals

Implications on Channel Model

With the above assumptions, the multi-path channel

reduces effectively to attenuation by a factor a.

a is complex Gaussian (multiplicative noise),

The magnitude |a| is Rayleigh distributed (Rayleigh fading).

Short frame duration implies a is constant during a frame.

Sampler,

N (t )

rate fs

bn s (t ) R (t ) R [n] to

× p (t ) × × + ΠTs (t )

DSP

∑ δ(t − nT ) A a

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 370](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-370-320.jpg)

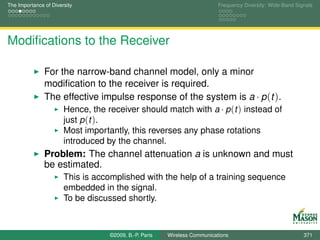

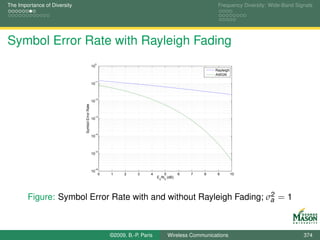

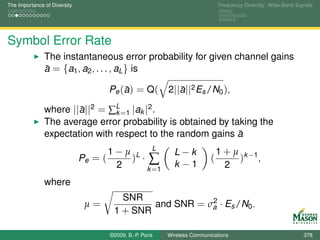

![The Importance of Diversity Frequency Diversity: Wide-Band Signals

Average Symbol Error Rate

The instantaneous symbol error rate varies from frame to

frame and depends on a.

The average symbol error rate provides a measure of

performance that is independent of the attenuation a.

It is obtained by averaging over a:

Pe = E[Pe (a)] = Pe (a) · PA (a) da,

where PA (a) is the pdf for the attenuation a.

For a complex Gaussian attenuation a with zero mean and

2

variance σa :

1 SNR

Pe = (1 − ),

2 1 + SNR

2

where SNR = σa · Es /N0 .

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 373](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-373-320.jpg)

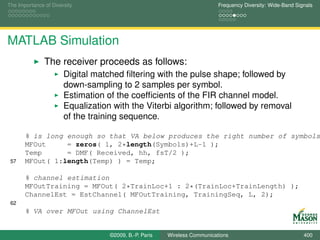

![The Importance of Diversity Frequency Diversity: Wide-Band Signals

MATLAB Simulation

The simulation begins with the generation of the

transmitted signal.

New facet: a known training sequence is inserted in the

middle of the frame.

%% simulate discrete-time equivalent system

% transmitter and channel via toolbox functions

InfoSymbols = RandomSymbols( NSymbols, Alphabet, Priors );

% insert training sequence

45 Symbols = [ InfoSymbols(1:TrainLoc) TrainingSeq ...

InfoSymbols(TrainLoc+1:end)];

% linear modulation

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 383](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-383-320.jpg)

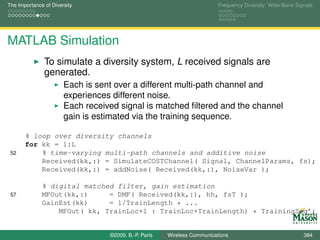

![The Importance of Diversity Frequency Diversity: Wide-Band Signals

MATLAB Simulation

The final processing step is maximum-ratio combining.

The matched filter outputs are multiplied with the conjugate

complex of the channel gains and added.

Multiplying with the conjugate complex of the channel gains

reverses phase rotations by the channel, and

gives more weight to strong channels.

61

% delete traning, MRC, and slicer

MFOut(:, TrainLoc+1 : TrainLoc+TrainLength) = [ ];

MRC = conj(GainEst)*MFOut;

Decisions = SimpleSlicer( MRC(1:NSymbols), Alphabet, ...

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 385](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-385-320.jpg)

![The Importance of Diversity Frequency Diversity: Wide-Band Signals

Maximum Likelihood Sequence Estimation

The principle behind MLSE is simple.

Given a received sequence of samples R [n], e.g., matched

filter outputs, and

a model for the output of the multi-path channel:

r [n] = s [n] ∗ h[n], where

ˆ

s [n] denotes the symbol sequence, and

h[n] denotes the discrete-time channel impulse response,

i.e., the channel taps.

Find the sequence of information symbol s [n] that

minimizes

N

D2 = ∑ |r [n] − s[n] ∗ h[n]|2 .

n

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 394](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-394-320.jpg)

![The Importance of Diversity Frequency Diversity: Wide-Band Signals

Maximum Likelihood Sequence Estimation

The criterion

N

D2 = ∑ |r [n] − s[n] ∗ h[n]|2 .

n

performs diversity combining (via s [n] ∗ h[n]), and

removes ISI.

The minimization of the above metric is difficult because it

is a discrete optimization problem.

The symbols s [n] are from a discrete alphabet.

A computationally efficient algorithm exists to solve the

minimization problem:

The Viterbi Algorithm.

The toolbox contains an implementation of the Viterbi

Algorithm in function va.

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 395](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-395-320.jpg)

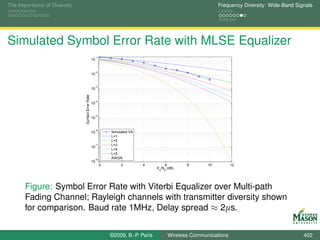

![The Importance of Diversity Frequency Diversity: Wide-Band Signals

MATLAB Simulation: System Parameters

Listing : VASetParameters.m

Parameters.T = 1/1e6; % symbol period

Parameters.fsT = 8; % samples per symbol

Parameters.Es = 1; % normalize received symbol energy to 1

Parameters.EsOverN0 = 6; % Signal-to-noise ratio (Es/N0)

13 Parameters.Alphabet = [1 -1]; % BPSK

Parameters.NSymbols = 500; % number of Symbols per frame

Parameters.TrainLoc = floor(Parameters.NSymbols/2); % location of t

Parameters.TrainLength = 40;

18 Parameters.TrainingSeq = RandomSymbols( Parameters.TrainLength, ...

Parameters.Alphabet, [0.5 0.5]

% channel

Parameters.ChannelParams = tux(); % channel model

23 Parameters.fd = 3; % Doppler

Parameters.L = 6; % channel order

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 397](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-397-320.jpg)

![The Importance of Diversity Frequency Diversity: Wide-Band Signals

MATLAB Simulation

The first step in the system simulation is the simulation of

the transmitter functionality.

This is identical to the narrow-band case, except that the

baud rate is 1 MHz and 500 symbols are transmitted per

frame.

There are 40 training symbols.

Listing : MCVA.m

41 % transmitter and channel via toolbox functions

InfoSymbols = RandomSymbols( NSymbols, Alphabet, Priors );

% insert training sequence

Symbols = [ InfoSymbols(1:TrainLoc) TrainingSeq ...

InfoSymbols(TrainLoc+1:end)];

46 % linear modulation

Signal = A * LinearModulation( Symbols, hh, fsT );

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 398](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-398-320.jpg)

![The Importance of Diversity Frequency Diversity: Wide-Band Signals

Channel Estimation

Channel Estimate:

h = (S S)−1 · S r,

ˆ

where

S is a Toeplitz matrix constructed from the training

sequence, and

r is the corresponding received signal.

TrainingSPS = zeros(1, length(Received) );

14 TrainingSPS(1:SpS:end) = Training;

% make into a Toepliz matrix, such that T*h is convolution

TrainMatrix = toeplitz( TrainingSPS, [Training(1) zeros(1, Order-1)]);

19 ChannelEst = Received * conj( TrainMatrix) * ...

inv(TrainMatrix’ * TrainMatrix);

©2009, B.-P. Paris Wireless Communications 401](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handouts-122962284592-phpapp01/85/Simulation-of-Wireless-Communication-Systems-401-320.jpg)