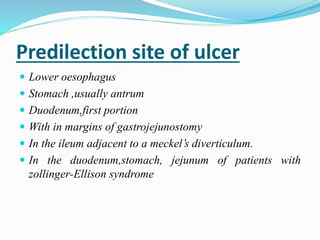

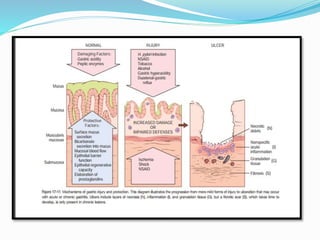

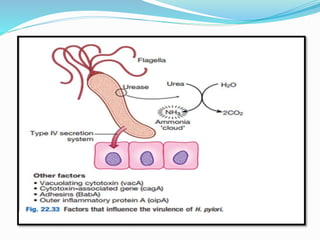

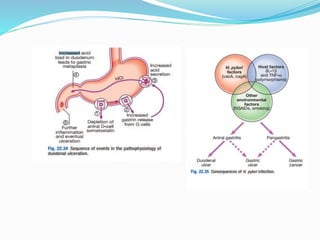

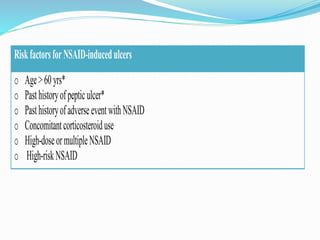

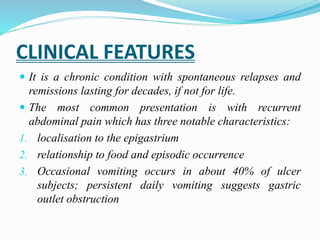

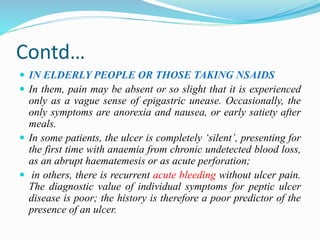

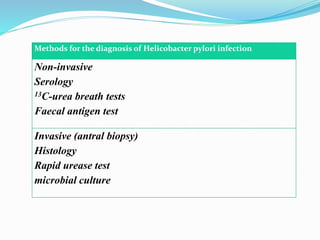

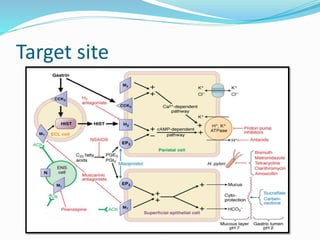

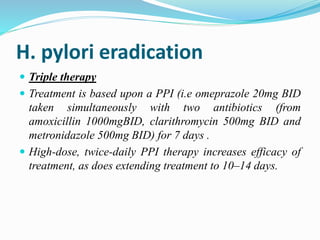

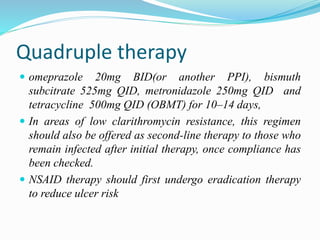

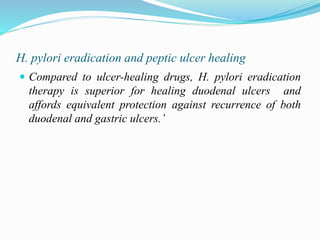

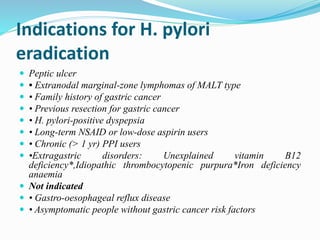

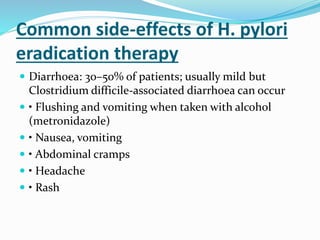

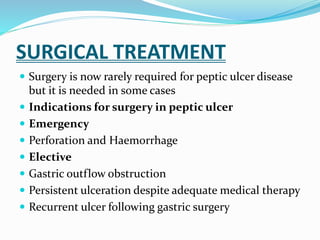

Peptic ulcers are lesions that occur in areas of the gastrointestinal tract exposed to stomach acid. Risk factors include H. pylori infection and NSAID use. Clinical features include recurrent abdominal pain related to food. Diagnosis involves endoscopy with biopsy or breath/stool tests for H. pylori. Management involves eradicating H. pylori with triple therapy antibiotics and PPIs. Surgery is rarely needed and reserved for complications like perforation or bleeding.