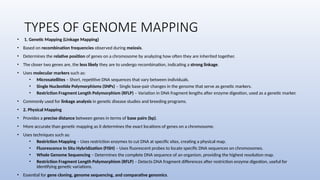

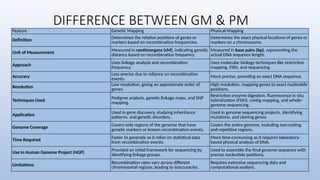

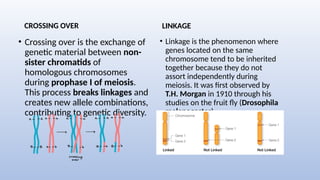

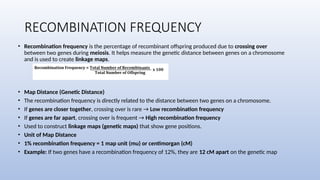

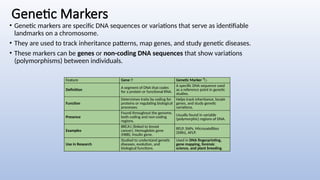

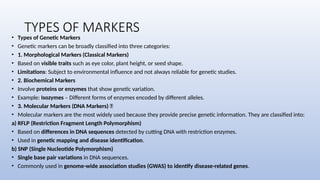

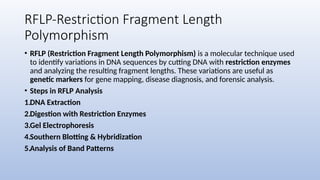

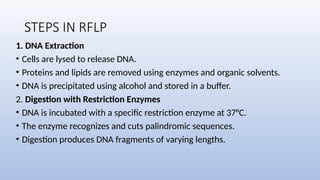

Genome mapping is a technique to identify gene locations and features within a genome, aiding in the understanding of gene function, inheritance, and disease mechanisms. It includes genetic mapping, which assesses relative positions based on recombination frequencies, and physical mapping, which provides exact physical positions. Applications span genetic disorder identification, crop improvement, forensic investigations, and personalized medicine development.