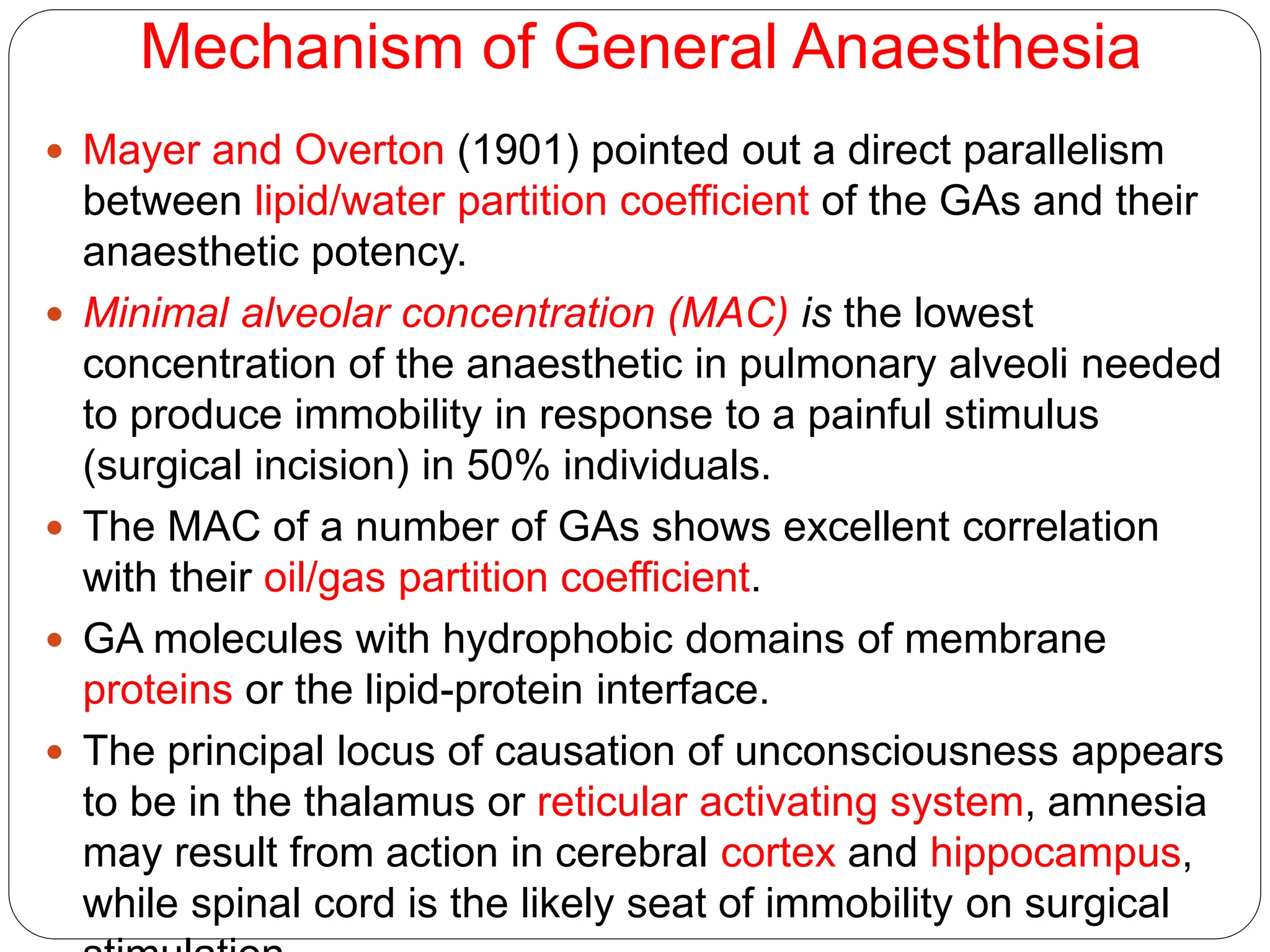

This document provides an overview of general anaesthetics. It discusses their history, mechanisms of action, stages of anaesthesia, pharmacokinetics, properties of an ideal anaesthetic, and classifications. Specific anaesthetics discussed include nitrous oxide, ether, and halothane. Nitrous oxide is described as having low potency but rapid induction and recovery. Ether has potent anaesthetic effects but is unpleasant to use due to irritating vapors. Halothane is nonirritating with intermediate solubility allowing quick induction.