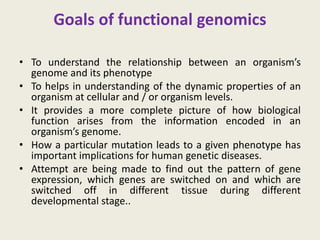

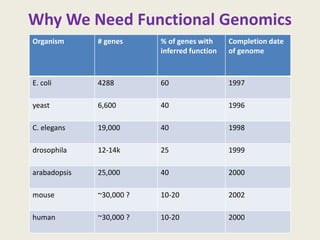

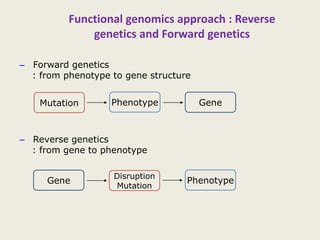

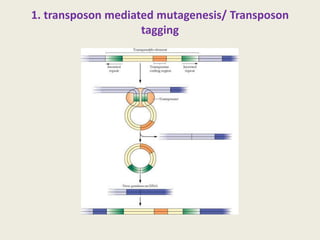

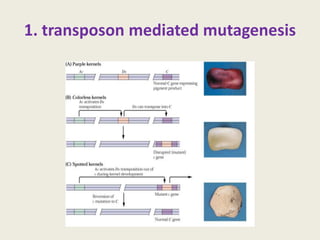

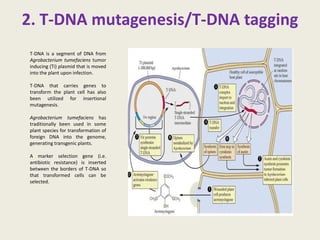

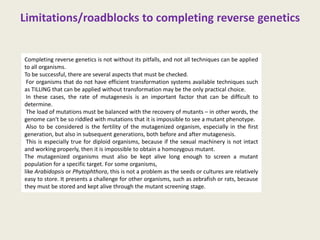

The document provides an overview of functional genomics, a field that studies gene functions and interactions using genomic data. It discusses the historical development, goals, methodologies, tools for forward and reverse genetics, as well as the limitations of these approaches. Emphasizing the importance of understanding how genes control phenotypes, the document underscores the dynamic nature of gene expression and the technological advancements that have facilitated research in this area.