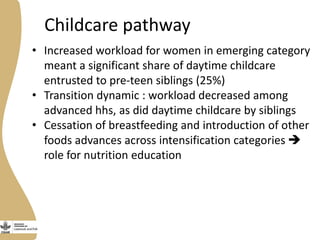

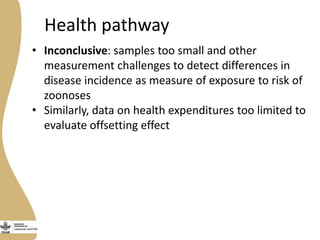

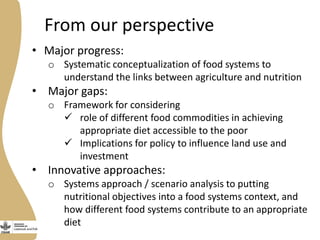

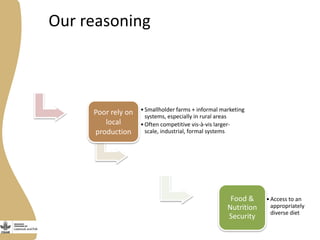

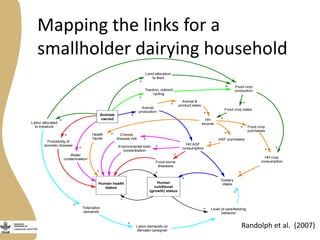

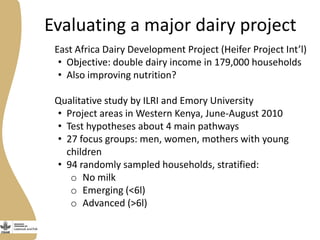

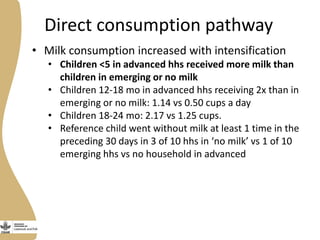

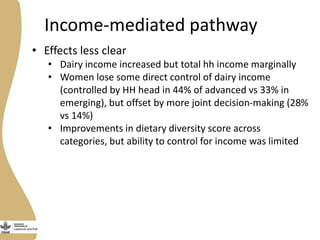

The document discusses ensuring access to animal-source foods for poor and nutritionally vulnerable populations. It argues that a multidimensional food systems approach is needed that considers production, access, and nutrition together. A case study of a dairy development project in East Africa found some evidence it increased milk consumption and child nutrition, though impacts were complicated by changes in household income control and women's workloads. More research is still needed to fully understand agriculture's role in nutrition within local food systems contexts.

![“MILK BELONGS TO THE WOMAN AND THE

MONEY BELONGS TO THE MAN”- MALE

FARMER, EMERGING GROUP, CHEBORGE

“MEAT IS A MUST WHEN WE GET PAID

[FROM THE DAIRY].”- MALE

FARMER, EMERGING GROUP, KIPKELION

Soundbites

FROM THE FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSIONS:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scienceforum2013randolph-130925033914-phpapp02/85/Ensuring-access-to-animal-source-foods-14-320.jpg)