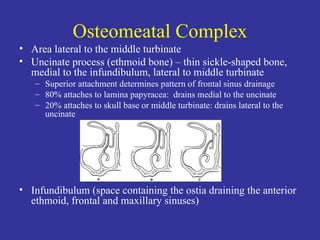

The document discusses sinus surgery and endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS). It covers the anatomy and embryology of the paranasal sinuses. It describes the osteomeatal complex and various sinus cells. It discusses techniques, complications, and post-operative care for FESS. It also mentions balloon sinuplasty as a newer minimally invasive technique for certain sinus diseases.