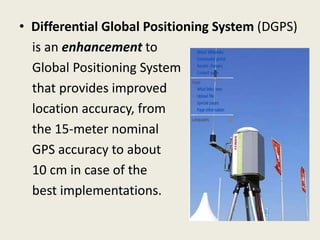

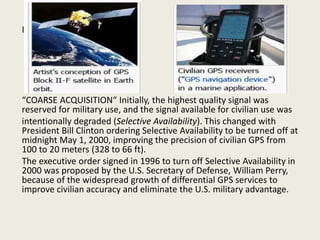

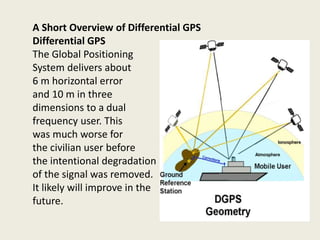

This document provides an overview of differential GPS (DGPS) and its history. It explains that DGPS uses fixed, ground-based reference stations to broadcast corrections to improve GPS accuracy from 15 meters to about 10 cm. Selective availability was introduced by the US military to degrade civilian GPS but was turned off in 2000. DGPS was developed as a solution, broadcasting corrections to offset errors and allow 5 meter accuracy, meeting most civilian needs. It has expanded to cover many waterways through systems like the US Coast Guard's National DGPS.

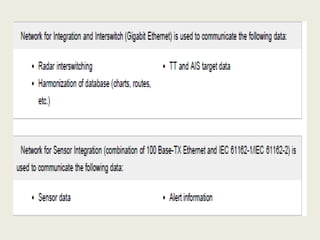

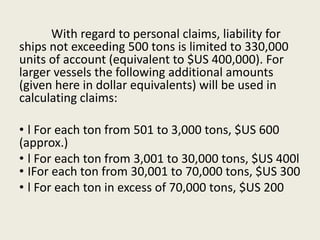

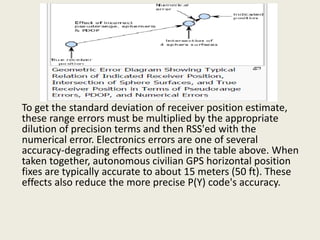

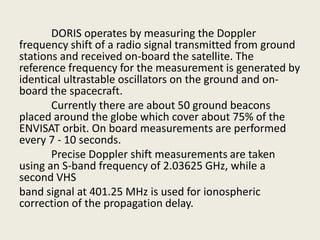

![• The improvement of GPS positioning doesn't require

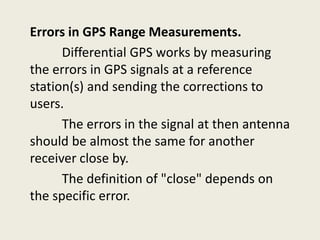

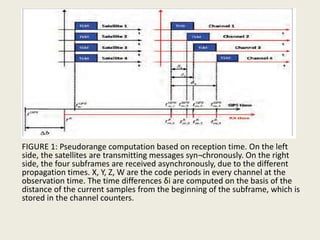

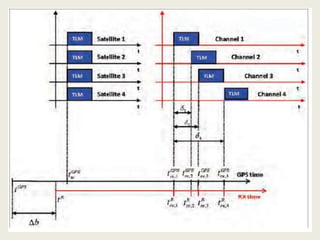

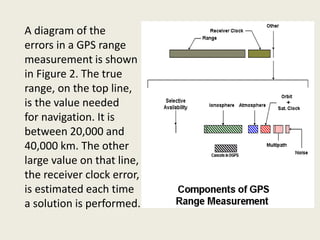

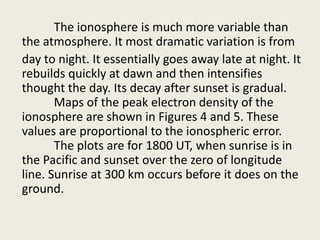

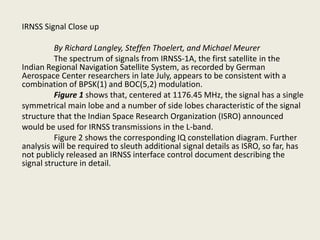

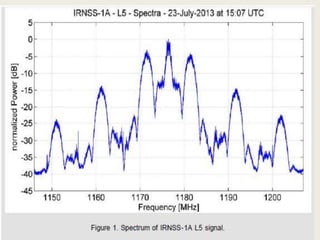

simultaneous measurements of two or more receivers in

any case, but can also be done by special use of a single

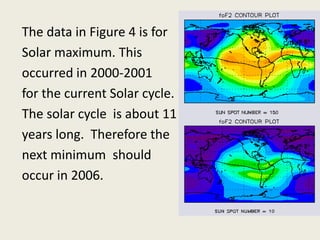

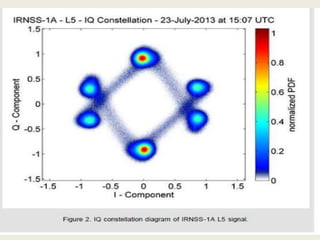

device.

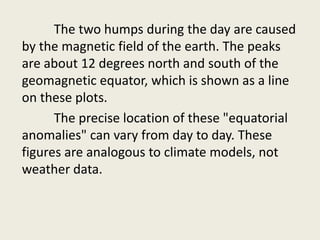

• In the 1990s when even handheld receivers were quite

expensive, some methods of Quasi-Differential [QDGPS]

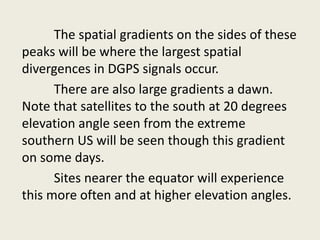

were developed, using the receiver by quick turns of

positions or loops of 3-10 survey points.

• QD - The analysis of errors computed using the Global

Positioning System is important for understanding how

GPS works, and for knowing what magnitude errors

should be expected. The Global Positioning System

makes corrections for receiver clock errors and other

effects but there are still residual errors which are not

corrected.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nav-5opruseecdis-150212205436-conversion-gate01/85/ECDIS-NAVIGATION-5-38-320.jpg)

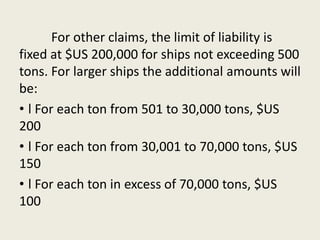

![The satellites would be launched 3 at a time on the

heavy-lift Proton rocket. Due to the large number of

satellites needed for the program, NPO PM

delegated the manufacturing of the satellites to PO

Polyot in Omsk, which had better production

capabilities.

Originally, GLONASS was designed to have an

accuracy of 65 m, but in reality it had an accuracy of

20 m in the civilian signal and 10 m in the military

signal.[6] The first generation GLONASS satellites

were 7.8 m tall, had a width of 7.2 m, measured

across their solar panels, and a mass of 1,260 kg.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nav-5opruseecdis-150212205436-conversion-gate01/85/ECDIS-NAVIGATION-5-132-320.jpg)

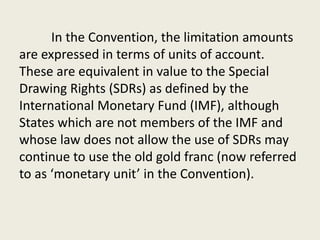

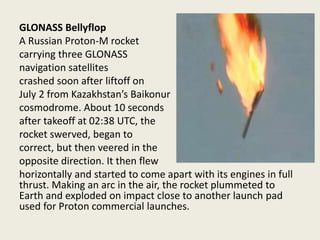

![The crashed Proton-M rocket employed a DM-03

booster, which was being used for the first time since

December 2010, when another Proton-M rocket with the

same booster failed to deliver another three GLONASS

satellites into orbit, crashing into the Pacific Ocean 1,500

kilometers from Honolulu.

A Russian government investigation revealed that at

least “three of six angular rate sensors [on the booster stage]

were installed incorrectly,” to be specific, upside-down.

Examination of the wreckage discovered traces of

forced, incorrect installation on three sensors. Assembly-line

testing at the factory failed to detect the faulty installation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nav-5opruseecdis-150212205436-conversion-gate01/85/ECDIS-NAVIGATION-5-140-320.jpg)

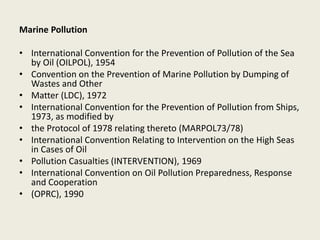

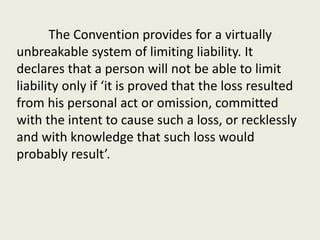

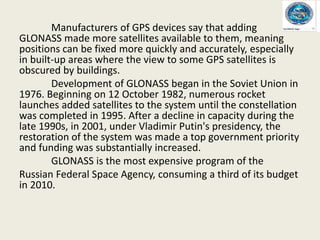

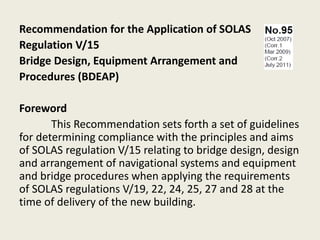

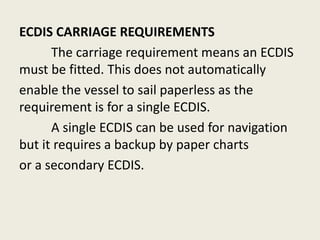

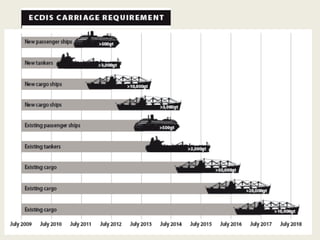

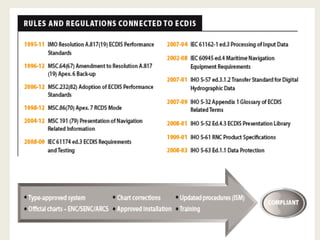

![REGULATIONS

ECDIS (as defined by IHO Publications S-52 and S-

57)[5] is an approved marine navigational chart and

information system, which is accepted as complying with

the conventional paper charts required by Regulation

V/19 of the 1974 IMO SOLAS Convention.[6] as amended.

The performance requirements for ECDIS are

defined by IMO and the consequent test standards have

been developed by the International Electrotechnical

Commission (IEC) in International Standard IEC 61174.[7]

The future standard for ENCs will be defined in IHO

Publication S-100.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nav-5opruseecdis-150212205436-conversion-gate01/85/ECDIS-NAVIGATION-5-268-320.jpg)