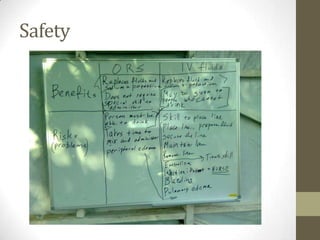

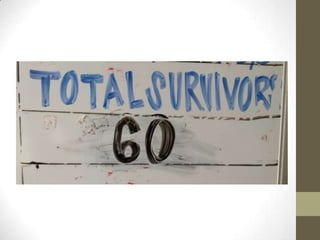

The document summarizes ethical issues that arise in treating patients with Ebola virus disease. It discusses principles of medical ethics like utilitarianism and deontology. It describes the author's experience working in an Ebola treatment unit in Sierra Leone. Key issues discussed include health worker safety, patient selection and triage if resources become overwhelmed, experimental treatments, and stigmatization of survivors.

![References

• Bausch, D. G., Towner, J. S., Dowell, S. F., Kaducu, F., Lukwiya, M., Sanchez, A., et al. (2007). Assessment of the risk of

Ebola virus transmission from bodily fluids and fomites. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 196(Supple. 2), S142-S147.

• Blumberg, L., Enria, D., & Bausch, D. G. (2014). Viral hemorrhagic fevers. In J. Farrar, P. J. Hotez, T. Junghanss, G. Kang, D.

Lalloo, & N. J. White (Eds.) Manson's tropical diseases, 23rd Ed. [Electronic version]. Elsevier.

• Chertow, D. S., Kleine, C., Edwards, J. K., Scaini, R., Giuliani, R., & Sprecher, A. (2014). Ebola virus disease in West Africa

– clinical manifestation and management. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(22), 2054-2057.

doi:10.1056/NEJMp1413084.

• Fowler, R. A., Fletcher, T., Fischer, W. A., Lomontagne, F., Jacob, S., Brett-Major, D., et al. (2014). Caring for critically ill

patients with Ebola virus disease. Perspectives from West Africa. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care

Medicine, 190(7), 733-737. doi:10.1164/rccm.201408-1514CP.

• Geisbert, T. W. (2014). Marburg and Ebola hemorrhagic fevers (Filoviruses). In J. E. Bennett, R. Dolin, & M. J. Blaser

(Eds.). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases, 8th Ed. [Electronic version].

Elsevier.

• Hartman, A. L. (2013). Ebola and Marburg virus infections. In, A. J. Magill, D. R. Hill, T. Solomon, & E. T. Ryan (Eds.)

Hunter's tropical medicine, 9th Ed. [Electronic version]. Elsevier.

• Hoenen, T., Groseth, A., Falzarano, D., & Feldman, H. (2006). Ebola virus: unravelling pathogenesis to combat a deadly

disease. TRENDS in Molecular Medicine, 12(5), doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.03.006.

• Kortepeter, M. G., Bausch, D. G., & Bray, M. (2011). Basic clinical and laboratory features of filoviral hemorrhagic fever.

Journal of Infectious Diseases, 204(Supple. 3), S810-S816.

• Schieffelin, J. S., Shaffer, J. G., Goba, A., Gbakie, M., Gire, S. K., Colubri, A., et al. (2014). Clinical illness and outcomes in

patients with Ebola in Sierra Leone. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(22), 2092-2100.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1411680.

• Towner, J. S., Rollin, P. E., Baucsh, D. G., Sanchez, A., Crary, S. M., Vincent, M., et al. (2004). Rapid diagnosis of Ebola

hemorrhagic fever by reverse transcription-PCR in an outbreak setting and assessment of patient viral load as a

predictor of outcome. Journal of Virology, 78(8), 4330-4341. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.8.4330–4341.2004.

• Yamin, D., Gertler, S., Ndeffo-Mbah, M. L., Skrip, L. A., Fallah, M., Nyenswah, T. G., et al. (2015). Effect of Ebola

progression on transmission and control in Liberia. Annals of Internal Medicine, 162(1), 11-17. doi:10.7326/M14-2255.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ebolaethicalissues-150125223432-conversion-gate02/85/Ebola-ethical-issues-9-320.jpg)

![References

• Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2005). Altered standards

of care in mass casualty events.

http://archive.ahrq.gov/research/altstand.

• Baize, S., Pannetier, D., Oestereich, L., Rieger, T., Koivogui, L.,

Magassouba, N., et al. (2014). Emergence of Zaire Ebola virus disease in

Guinea. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(15),1418-1425.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1404505.

• Blumberg, L., Enria, D., & Bausch, D. G. (2014). Viral hemorrhagic fevers.

In J. Farrar, P. J. Hotez, T. Junghanss, G. Kang, D. Lalloo, & N. J. White

(Eds.) Manson's tropical diseases, 23rd Ed. [Electronic version]. Elsevier.

• Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (October 3, 2014). Ebola

virus disease outbreak – Nigeria, July-September, 2014. Morbidity and

Mortality Weekly Report, 63(39), 867-872.

http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6339a5.htm.

• Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (November 20, 2014).

Interim guidance for healthcare workers providing care in West African

countries affected by the Ebola outbreak: limiting heat burden while

wearing personal protective equipment (PPE).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ebolaethicalissues-150125223432-conversion-gate02/85/Ebola-ethical-issues-40-320.jpg)