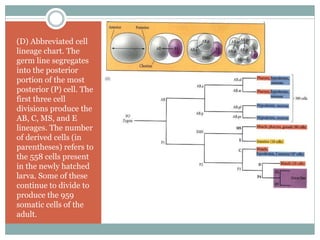

The document describes developmental patterns in several animal phyla. It discusses:

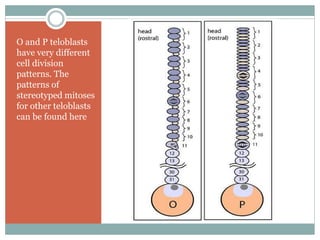

1) Spiral cleavage in mollusks and annelids, where cleavage planes are oblique, forming a spiral arrangement. This results in cells touching at more points than radially cleaving embryos.

2) Developmental axes in C. elegans defined by the anterior-posterior axis of the egg. The sperm entry point determines the posterior pole.

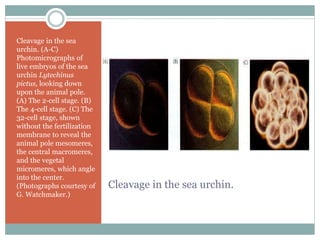

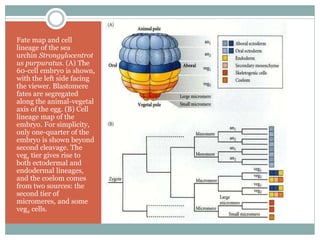

3) Radial holoblastic cleavage in sea urchins, where the first three cleavages are perpendicular, forming cell tiers, while the fourth cleavage divides cells meridionally.