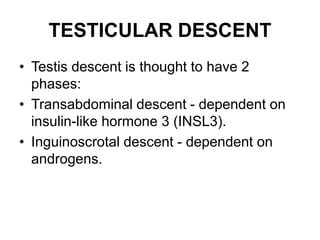

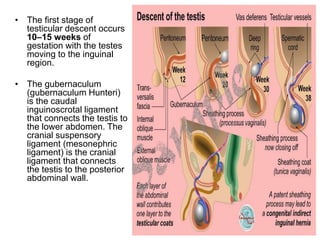

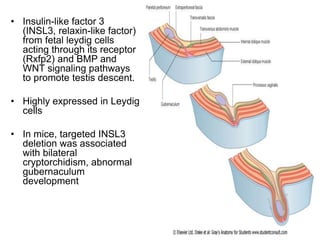

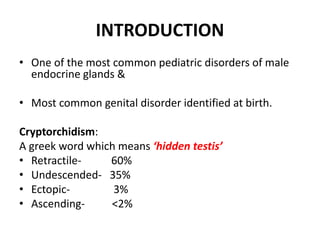

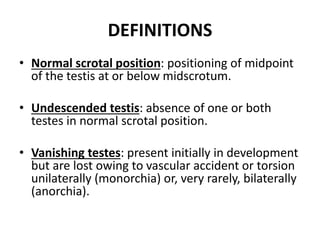

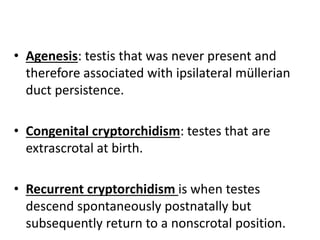

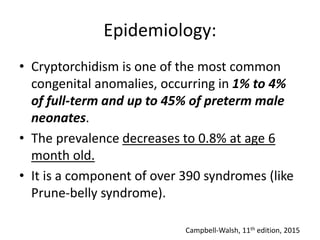

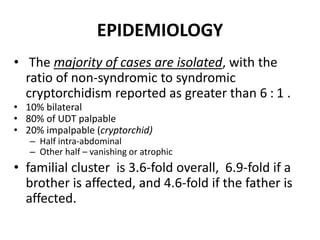

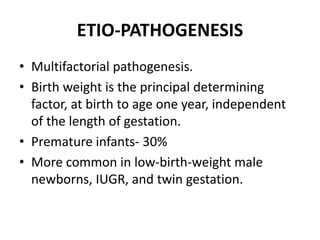

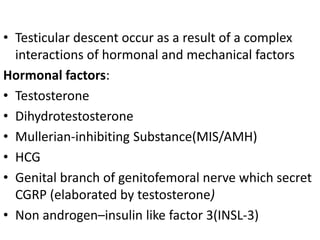

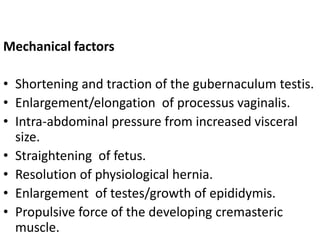

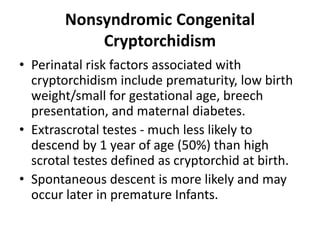

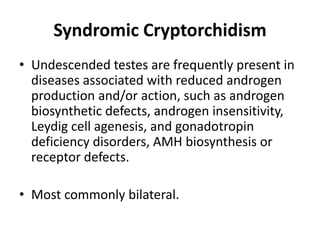

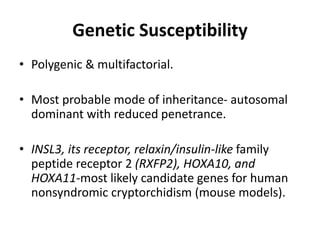

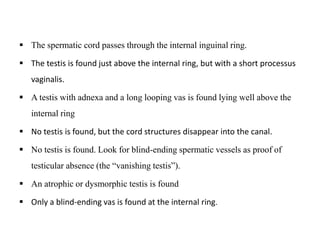

Cryptorchidism, or undescended testes, is a common birth defect where one or both testes fail to descend into the scrotum. It results from complex interactions between hormonal and mechanical factors during fetal development. The condition affects 1-4% of full-term and up to 45% of preterm male infants. Risk factors include low birth weight, prematurity, and genetic susceptibility. While often isolated, cryptorchidism can also be associated with syndromes involving reduced androgen production or action. Spontaneous descent is more likely in premature infants and may occur later in the first year of life.

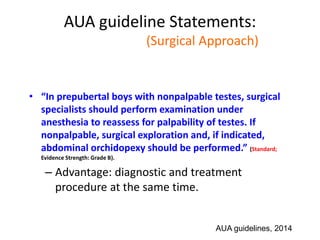

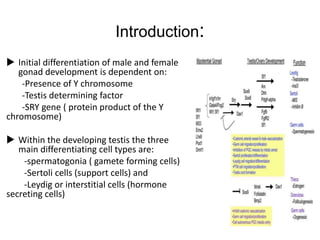

![AUA guideline Statements:

Statement#8

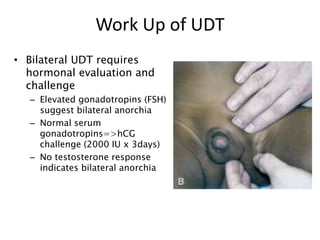

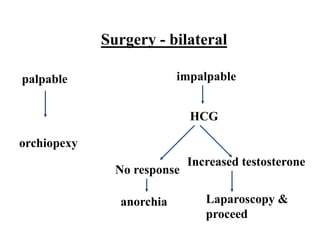

• “In boys with bilateral, nonpalpable testes who

do not have congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH),

providers should measure Müllerian Inhibiting

Substance (MIS or Anti- Müllerian Hormone

[AMH]) and consider additional hormone testing

to evaluate for anorchia.” (Option; Evidence Strength: Grade C).

– Patient who has bil nonpalpable UDT with 46 XY

karyotype, may have hormonal workup or wait until

age 6 months to undergo laparoscopic exploration.

– Hormonal workup: Tes, LH, FSH, hCG stimulation test,

and MIS.

AUA guidelines, 2014](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/developmentoftestispresentation-170107164608/85/Development-of-testis-cryptorchidism-presentation-117-320.jpg)