This document introduces the concept of the derivative and rate of change in mathematics. It defines the derivative as the slope of the tangent line to a curve at a point, which can be interpreted as the instantaneous rate of change of the dependent variable with respect to the independent variable. The document provides examples of calculating derivatives and interpreting them in the context of rates of change. It then discusses how to view the derivative not just at a single point, but as a new function defined for all points where the limit exists, known as the derivative function.

![20

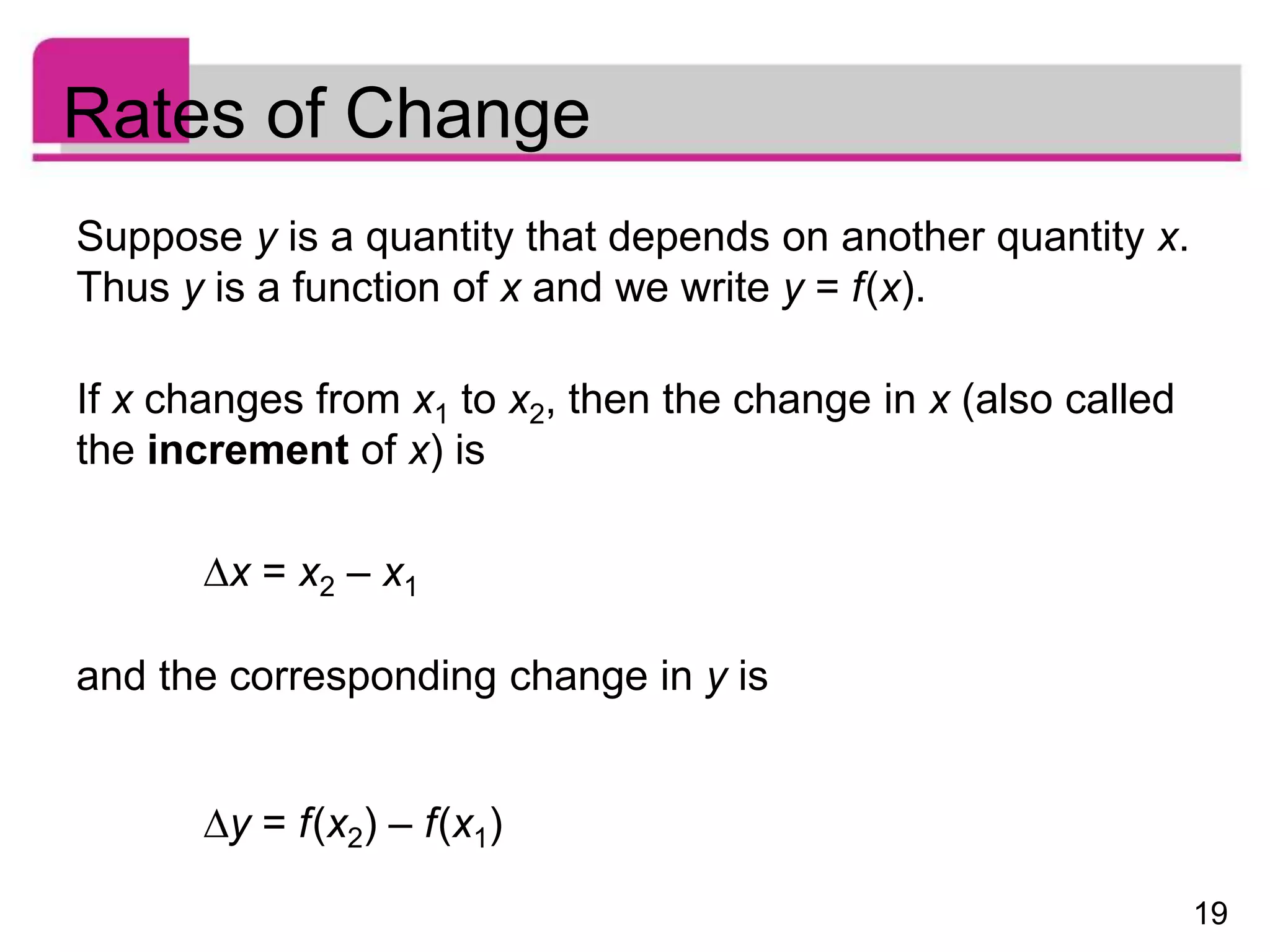

Rates of Change

The difference quotient

is called the average rate of

change of y with respect to x

over the interval [x1, x2] and

can be interpreted as the slope

of the secant line PQ

in Figure 8.

Figure 8

average rate of change = mPQ

instantaneous rate of change =

slope of tangent at P](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/derivative1-221106052641-2b22aa40/75/Derivative-1-ppt-20-2048.jpg)