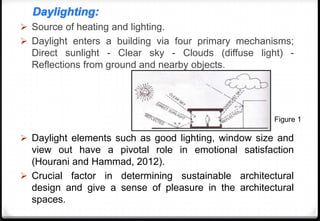

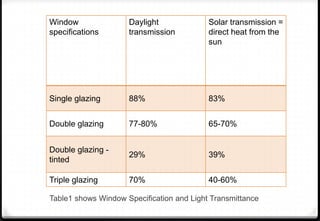

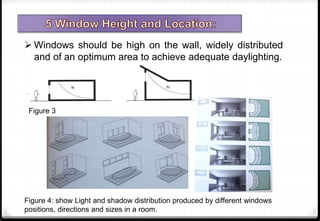

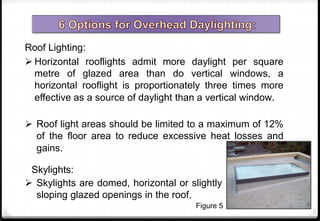

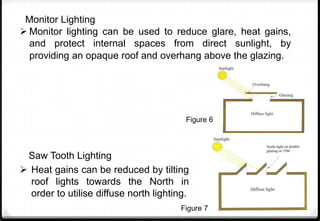

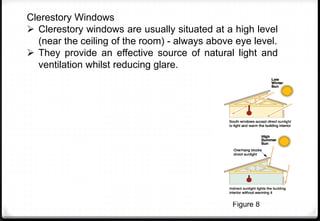

This document discusses the principles of effective daylight design in architecture. It outlines how daylight enters buildings and factors like orientation, glazing size and position, and glazing type impact daylight levels. Effective daylight design considers the building form, orientation, and use of windows, skylights, clerestory windows, and monitors to optimize natural light distribution while reducing glare and heat gains/losses. The document provides guidance on designing healthy buildings with controlled natural lighting according to room needs.

![ DUXBURY, Liane (2013). Daylight and Modeling Case Studies (2013)

GUZOWSKI, Mary. (2000). Daylighting for sustainable design. New York, McGraw-Hill.

HOURANI, May, and HAMMAD, Rizeq (2012). Impact of daylight quality on architectural space

dynamics: Case study: City Mall--Amman, Jordan. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews,

16 (6), 3579-3585.

LECHNE, Norbert. (2009). Heating, cooling, lighting: sustainable design methods for

architects. 3rd ed., Canada, John Wiley, Hoboken and NJ.

PHILLIPS, Derek. (2004). Daylighting: natural light in architecture. Oxford,

Architectural Press.

SMITH, Peter F. (2005). Architecture in a climate of change: A guide to sustainable

design. 2nd ed., Oxford, Architectural Press.

YAO, J. and ZHU, N. (2012). Evaluation of indoor thermal environmental, energy and

daylighting performance of thermotropic windows. [online]. Building and Environment, 49,

283-29. Article from Science Direct last accessed 21 August 2013 at:

http://www.sciencedirect.c.

References](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/daylightingslideshare-151021183128-lva1-app6892/85/Daylighting-slideshare-14-320.jpg)