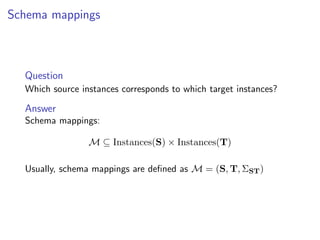

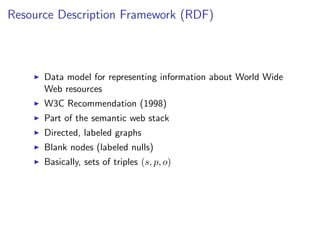

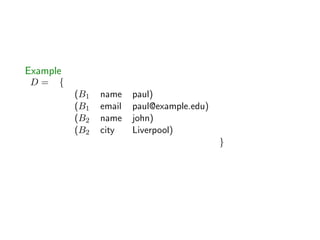

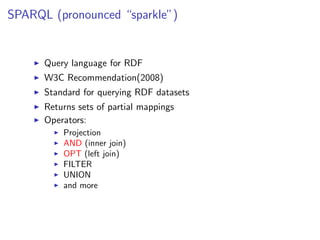

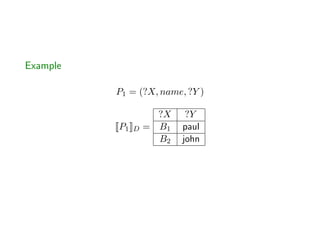

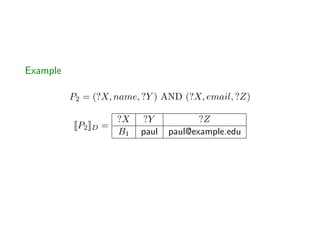

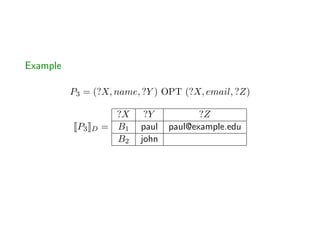

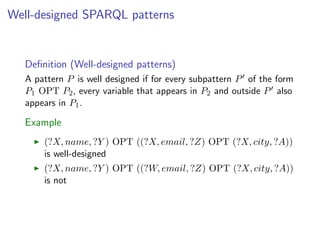

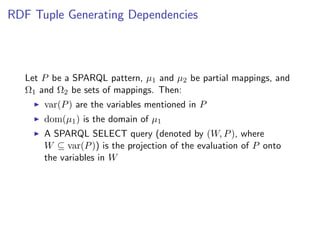

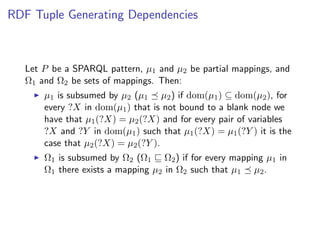

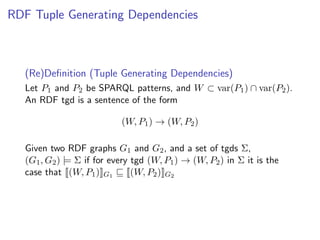

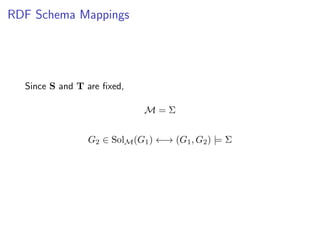

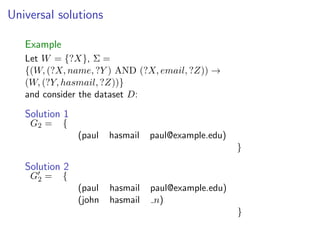

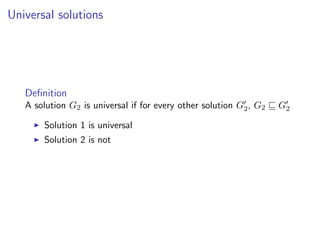

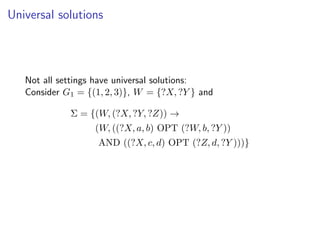

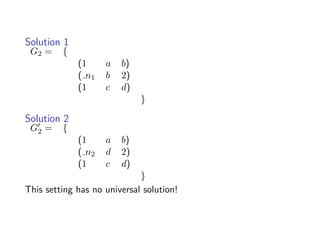

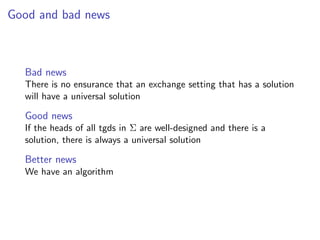

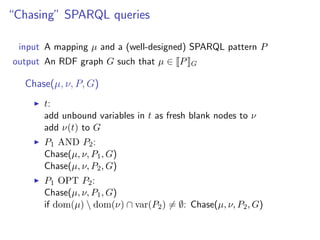

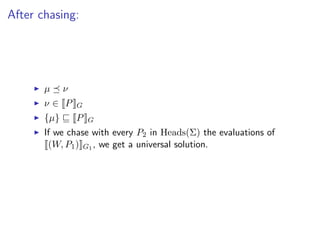

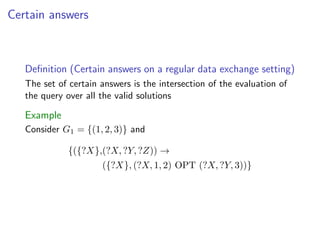

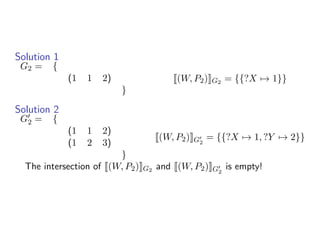

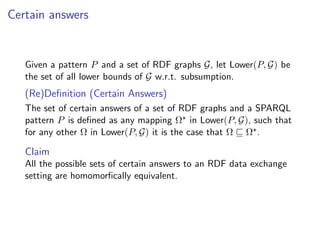

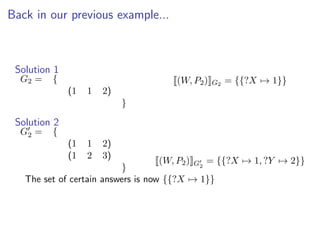

This document summarizes research on data exchange over Resource Description Framework (RDF) graphs. It defines RDF tuple generating dependencies that allow translating data between RDF schemas. It shows that if the heads of tuple generating dependencies are well-designed, there is always a universal solution for data exchange. It also defines certain answers for SPARQL queries over RDF data exchange as the intersection of answers over all valid solutions. The document outlines contributions made so far and future work on query answering, handling incomplete source data, and knowledge exchange over RDF graphs.