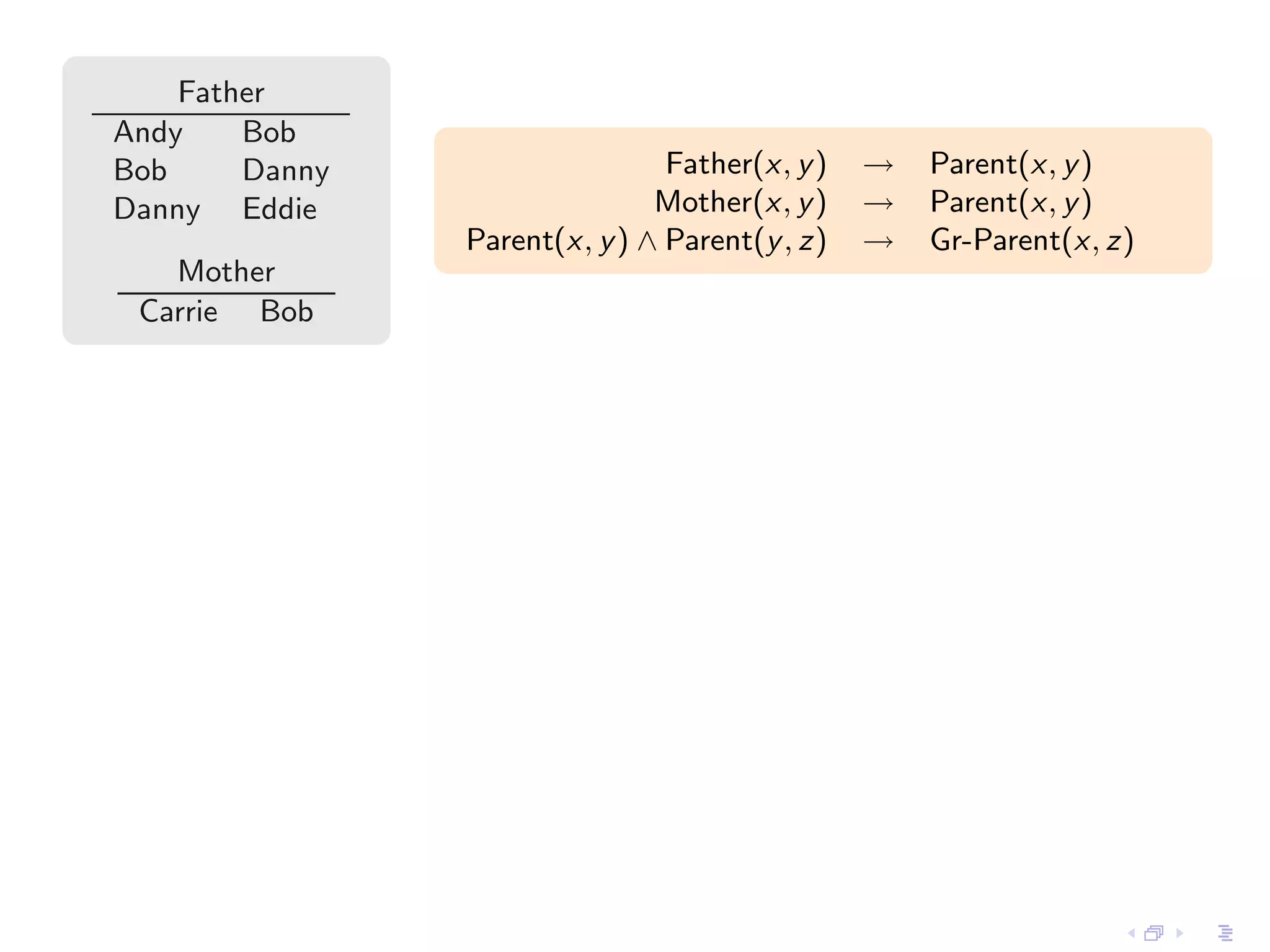

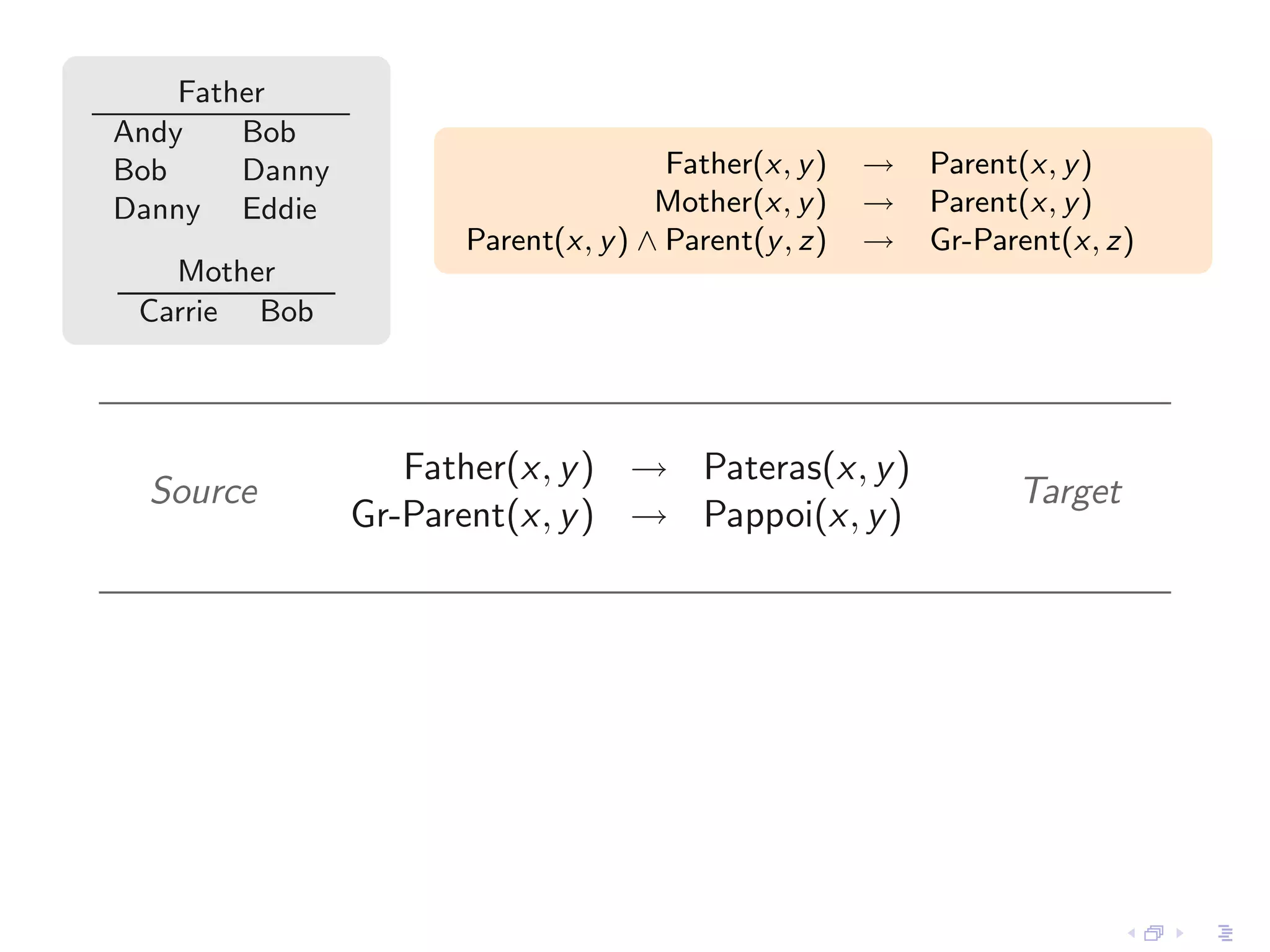

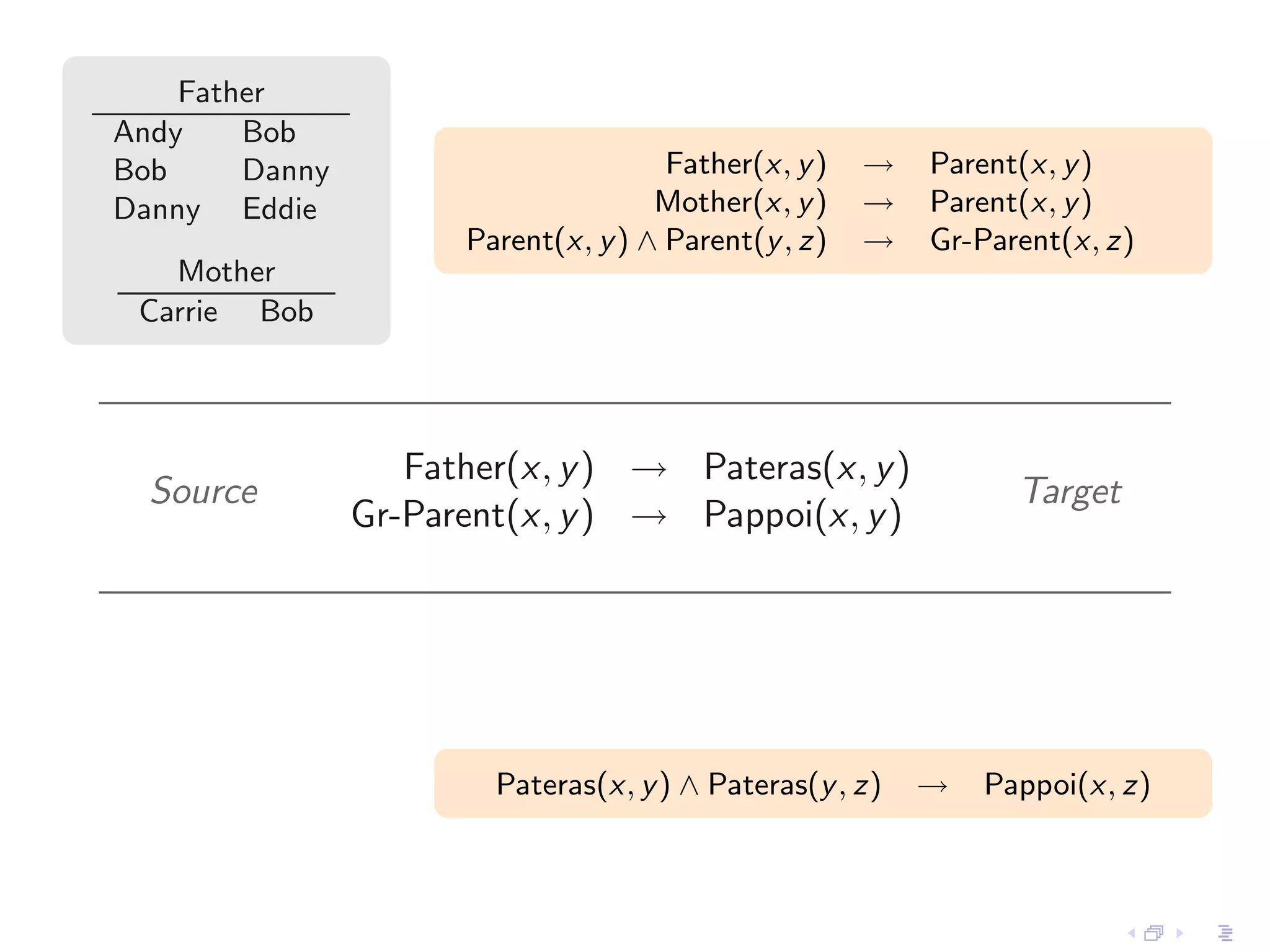

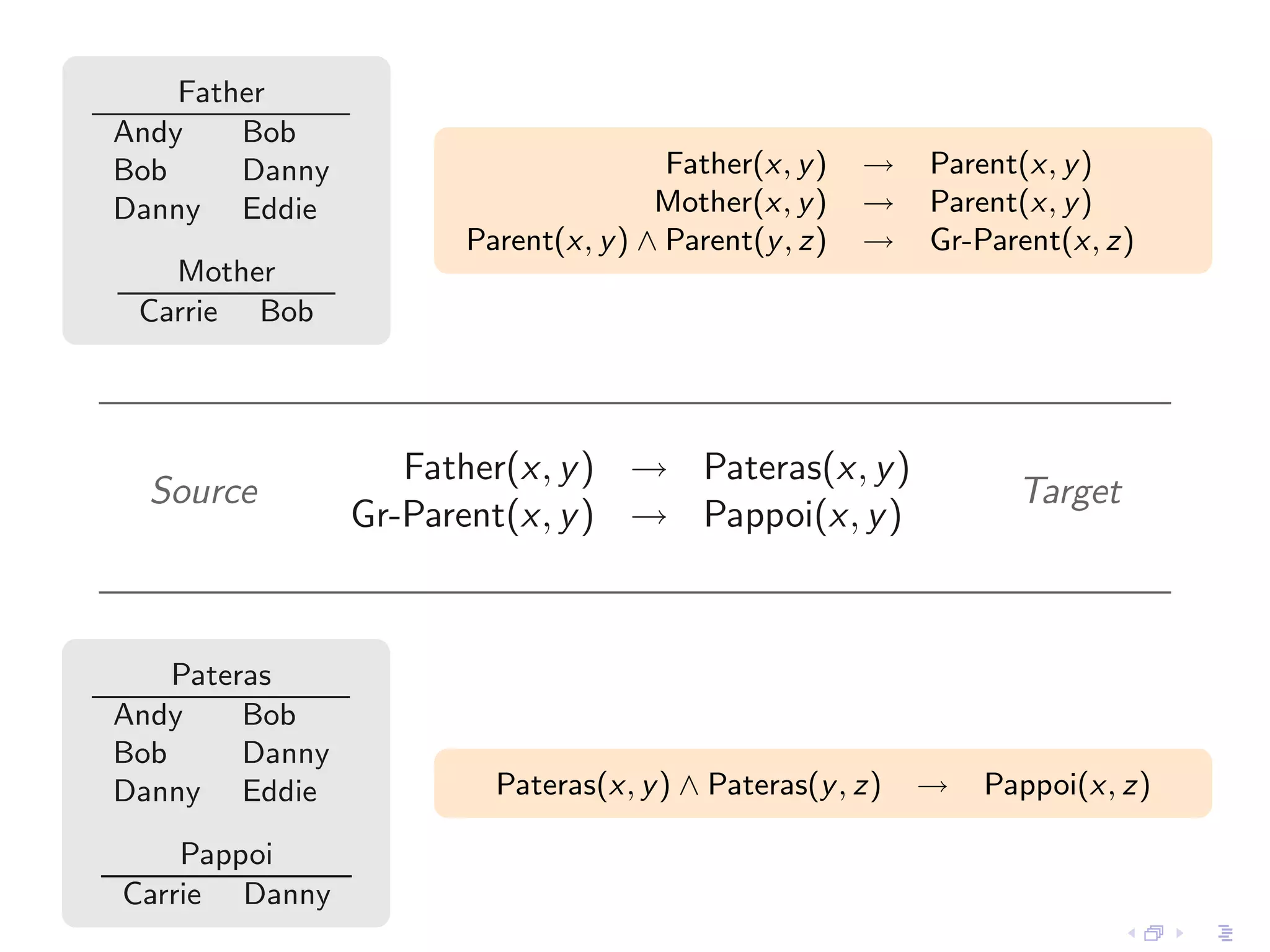

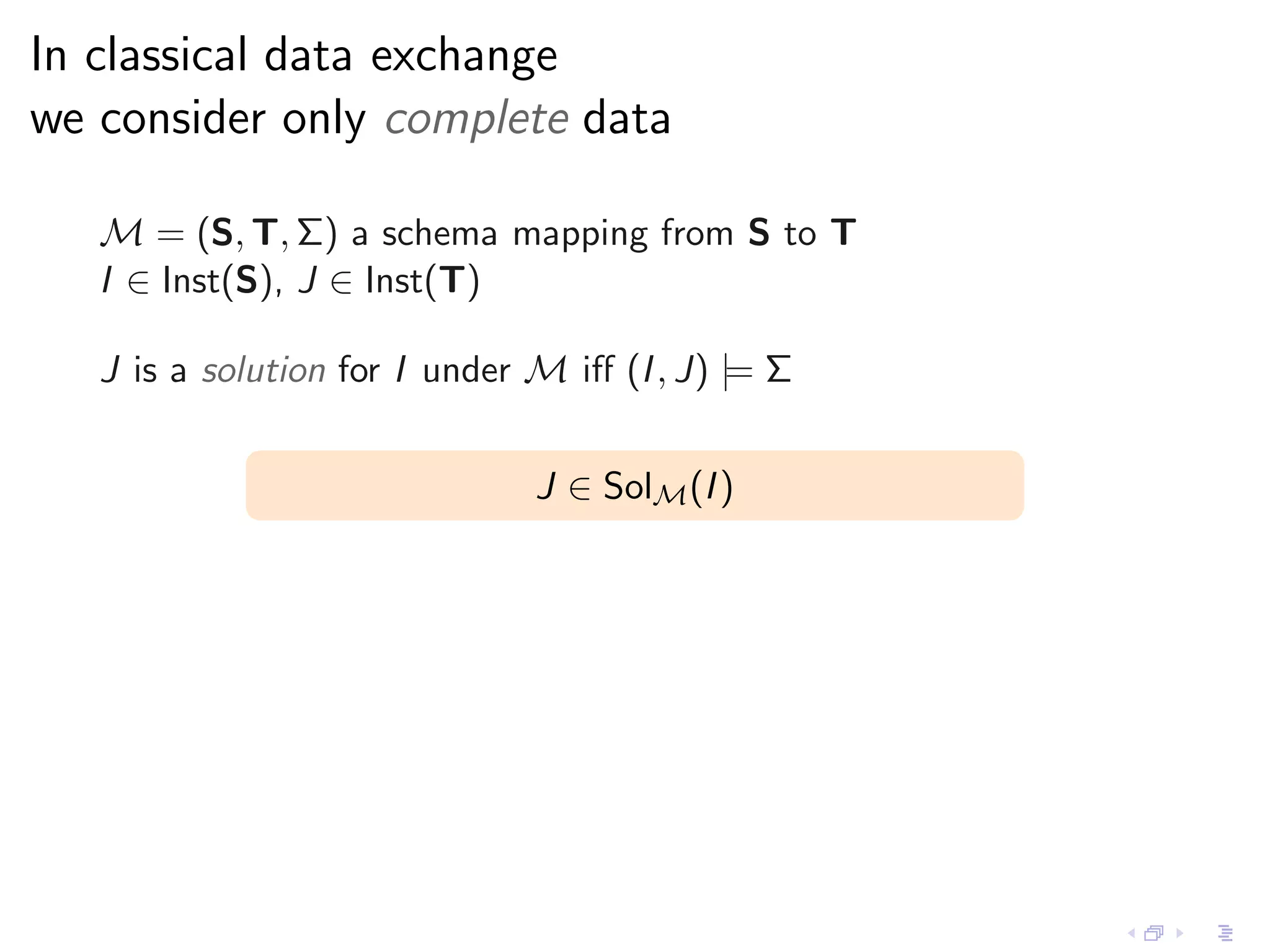

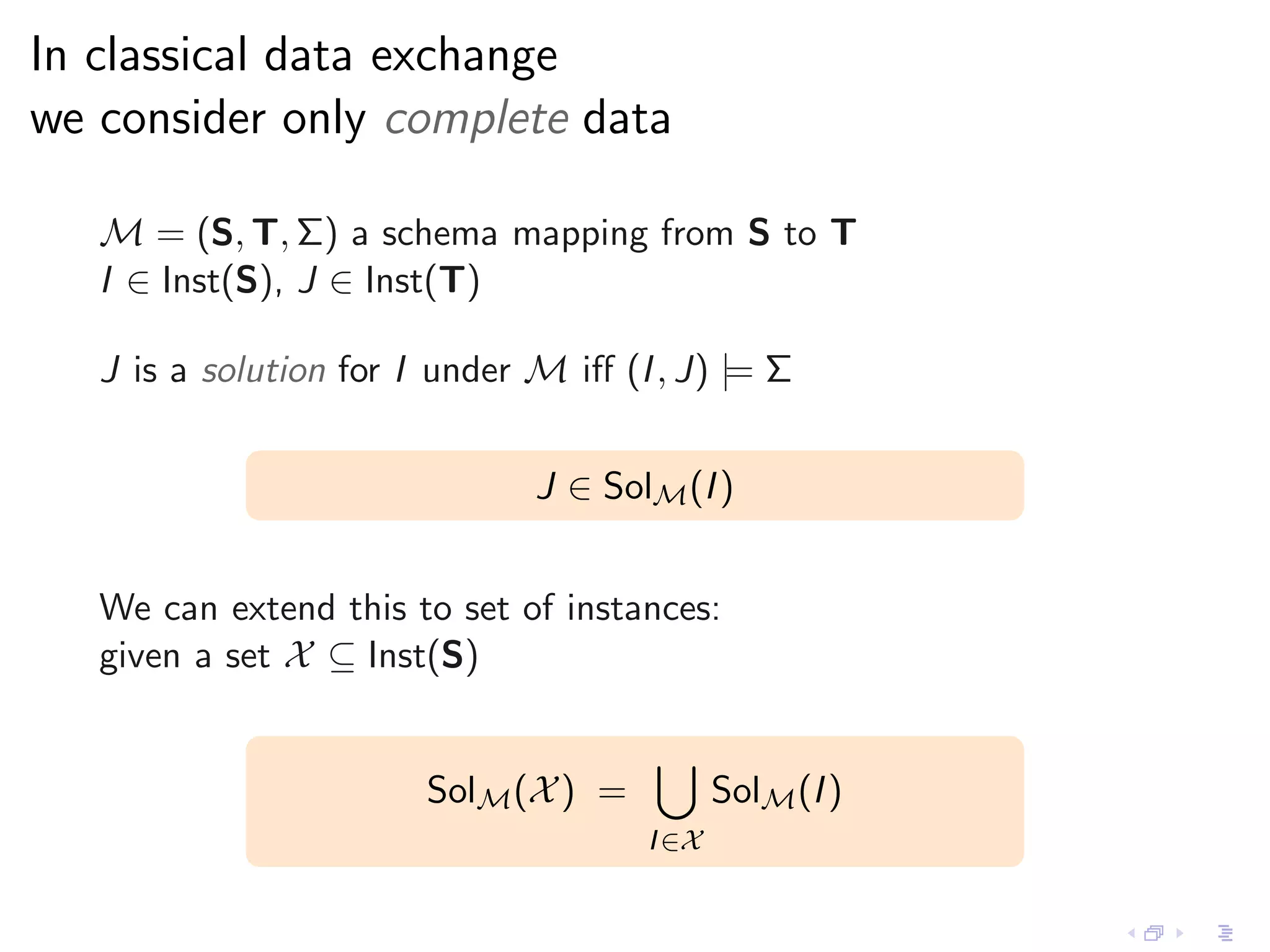

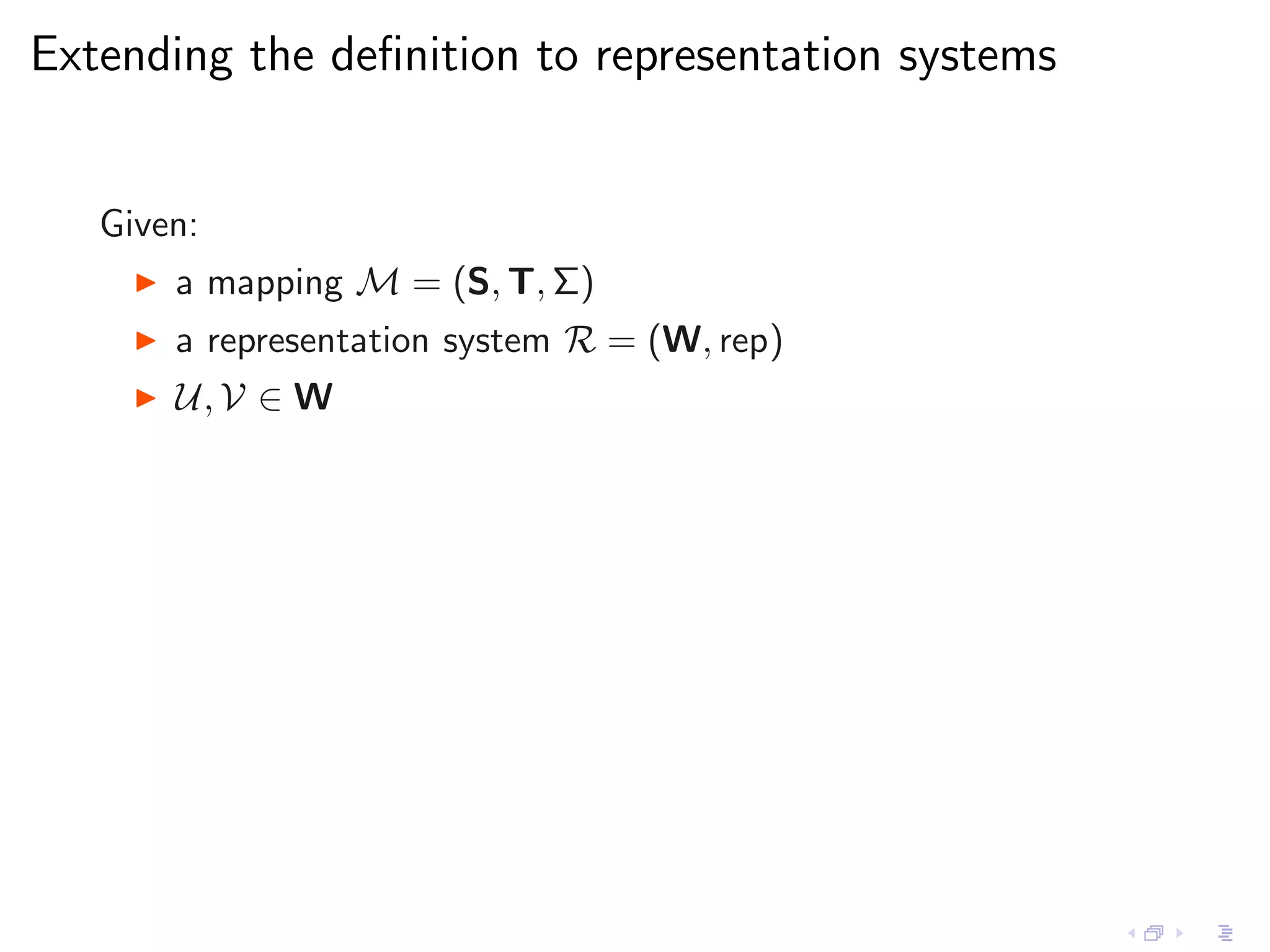

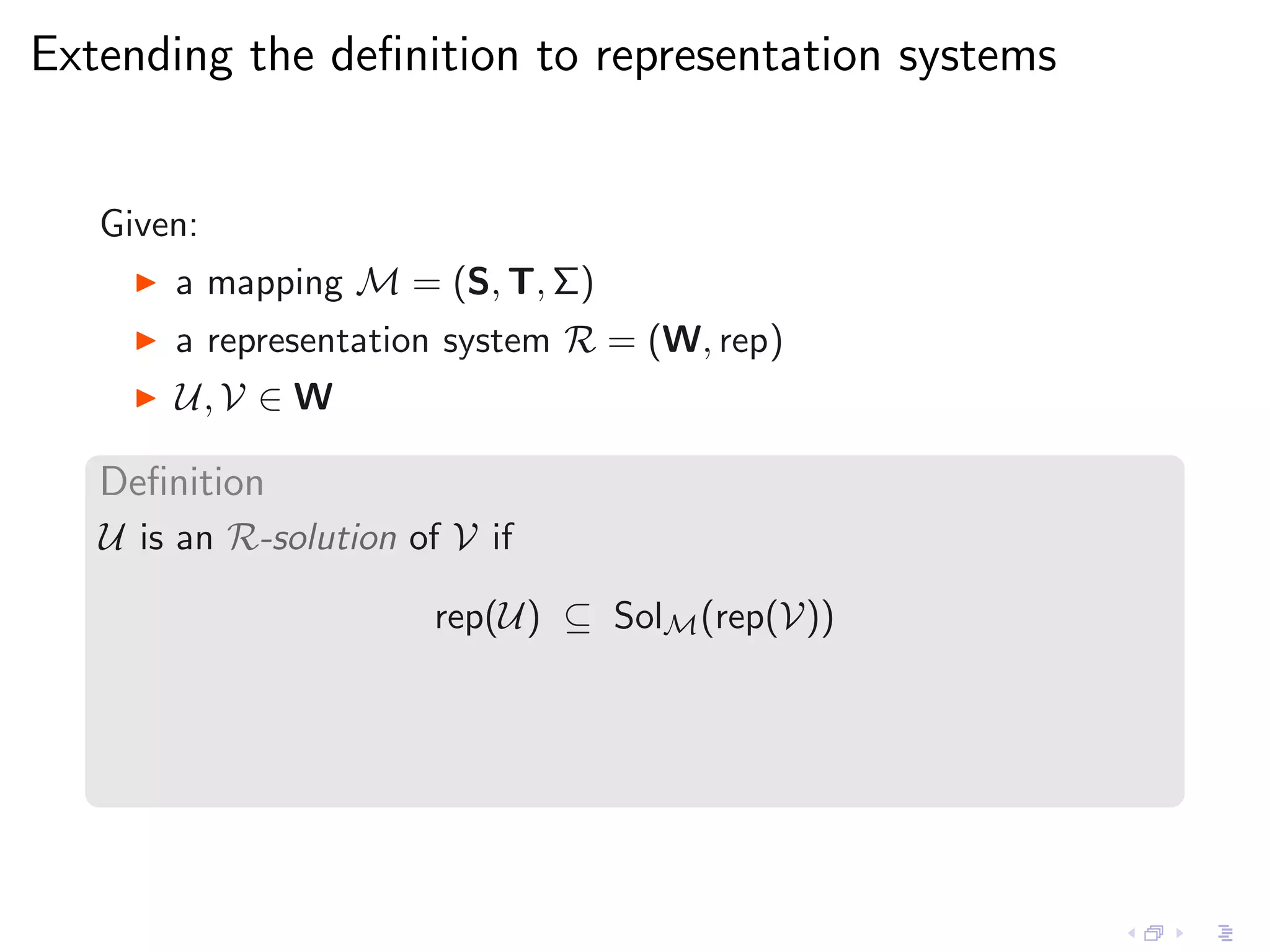

- The document discusses exchanging more than just complete data between databases, by using representation systems that can capture sets of possible instances.

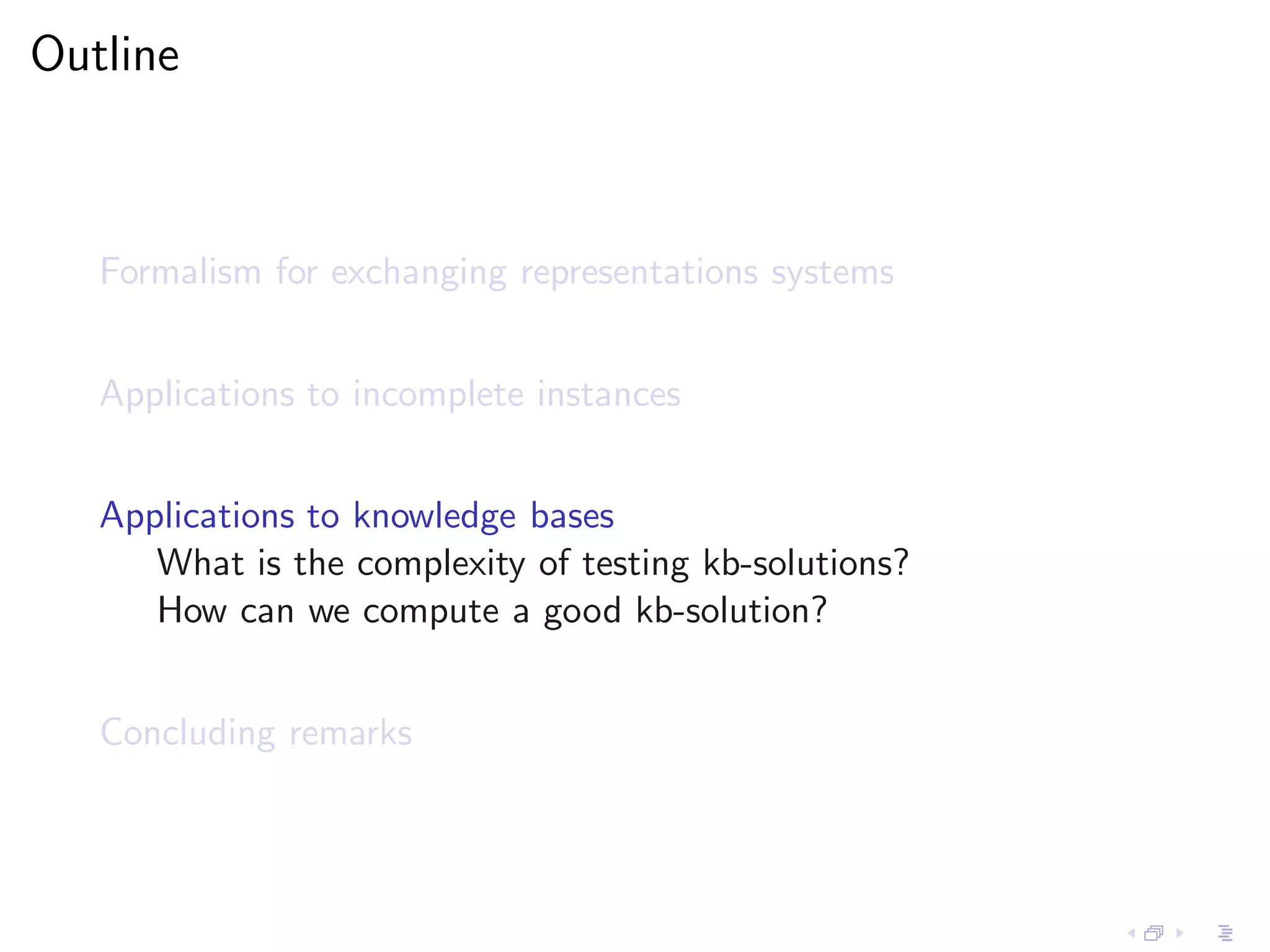

- It proposes a formalism for exchanging representations between systems and applies this to incomplete instances and knowledge bases.

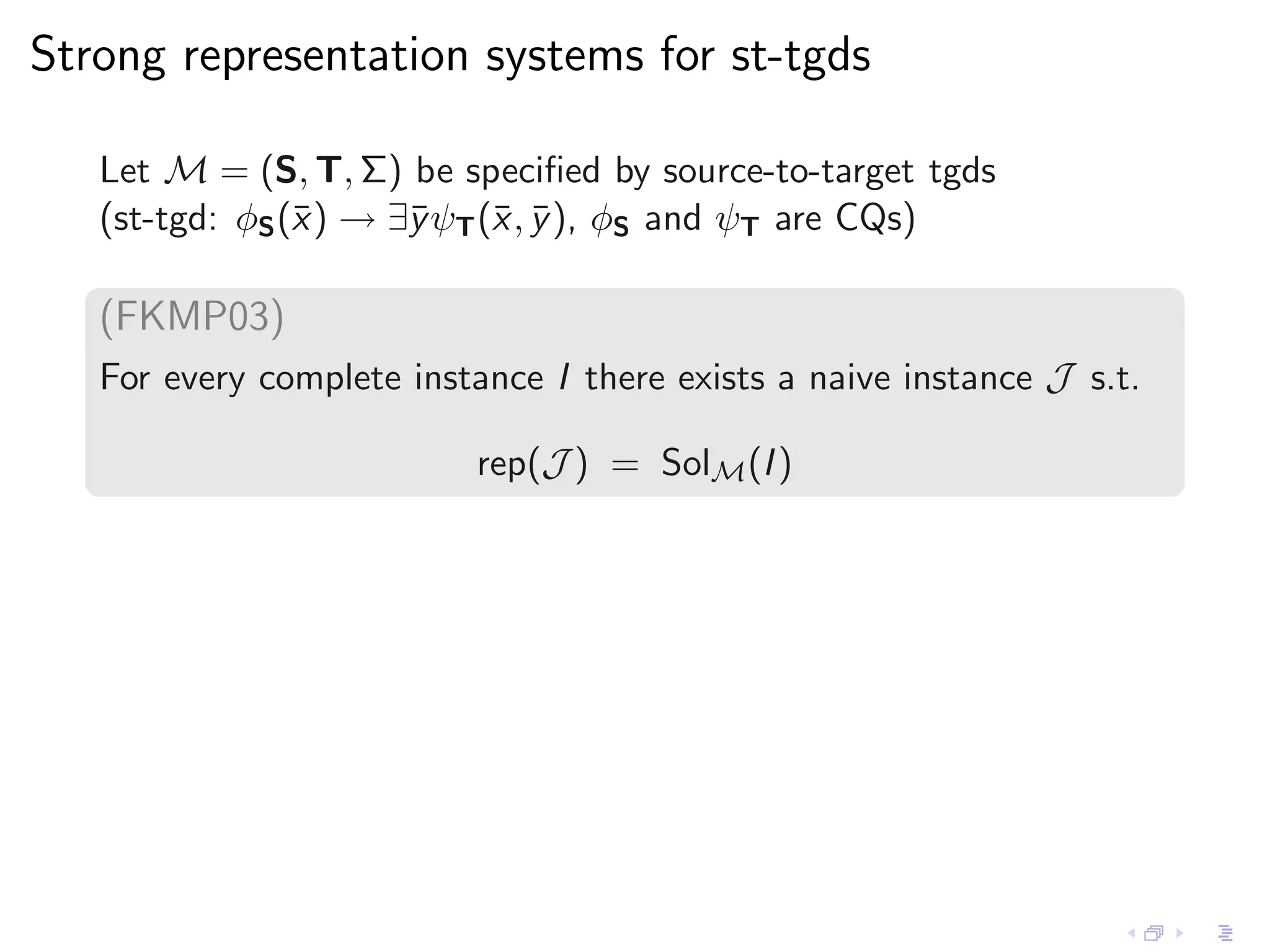

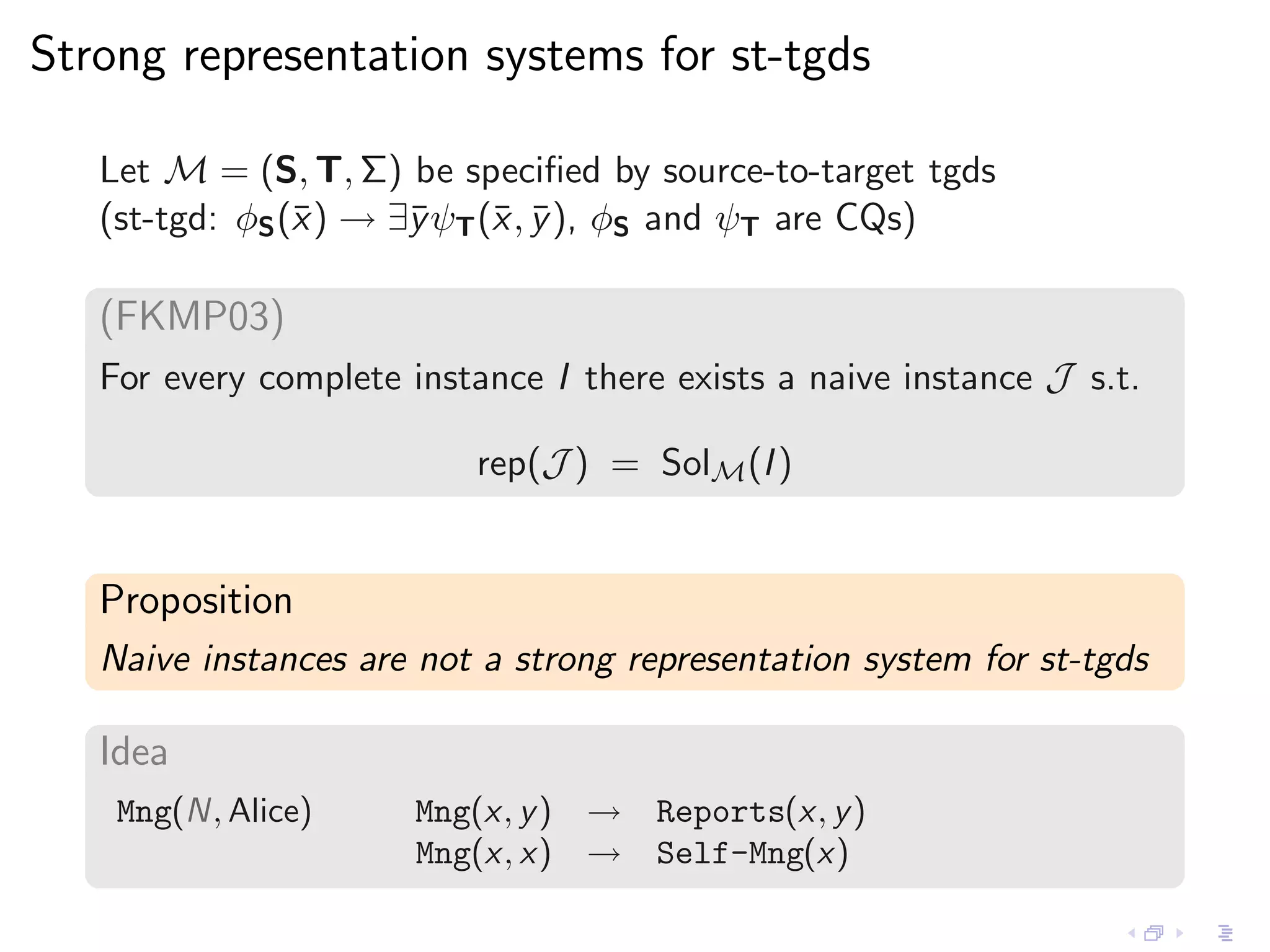

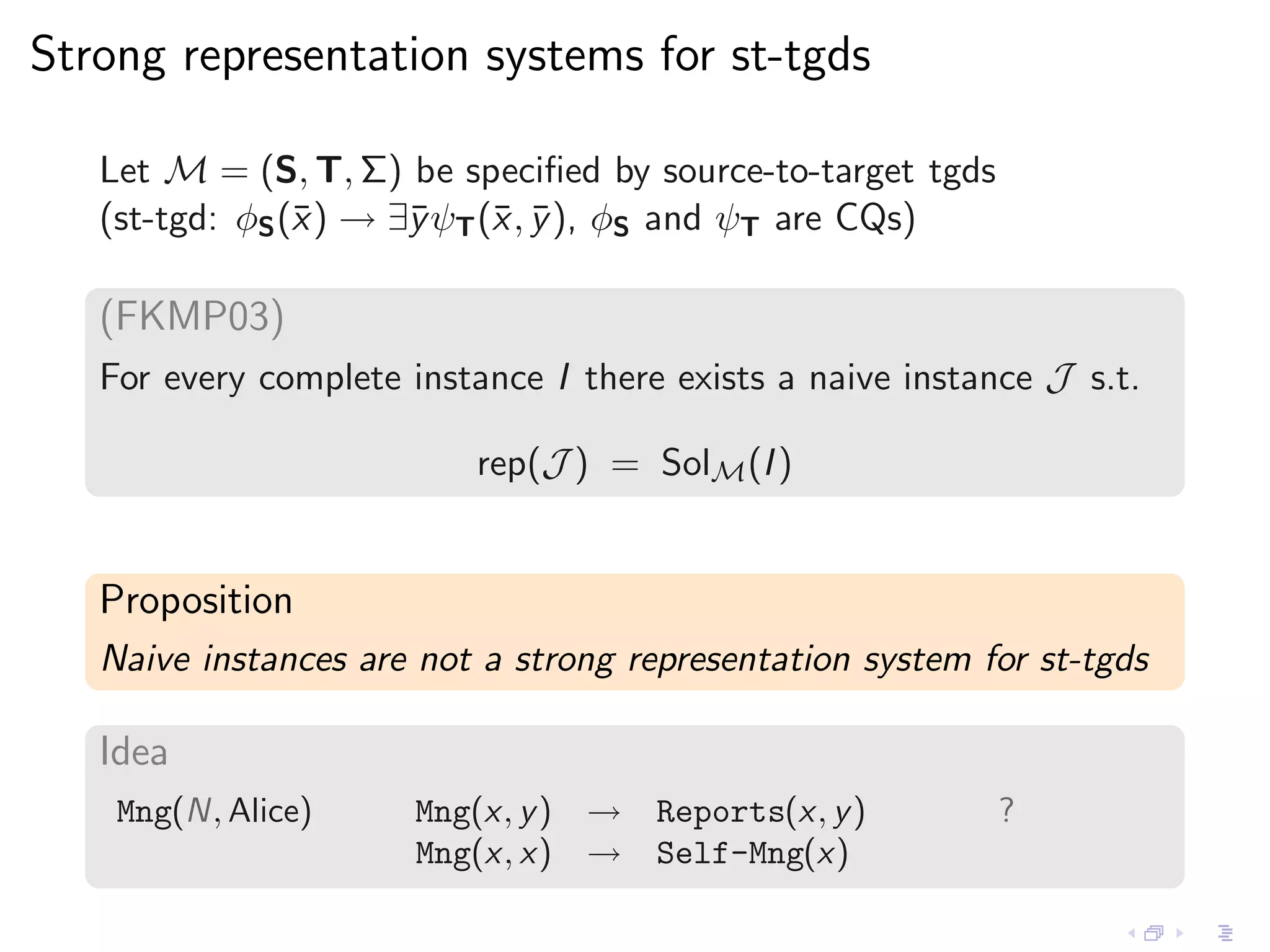

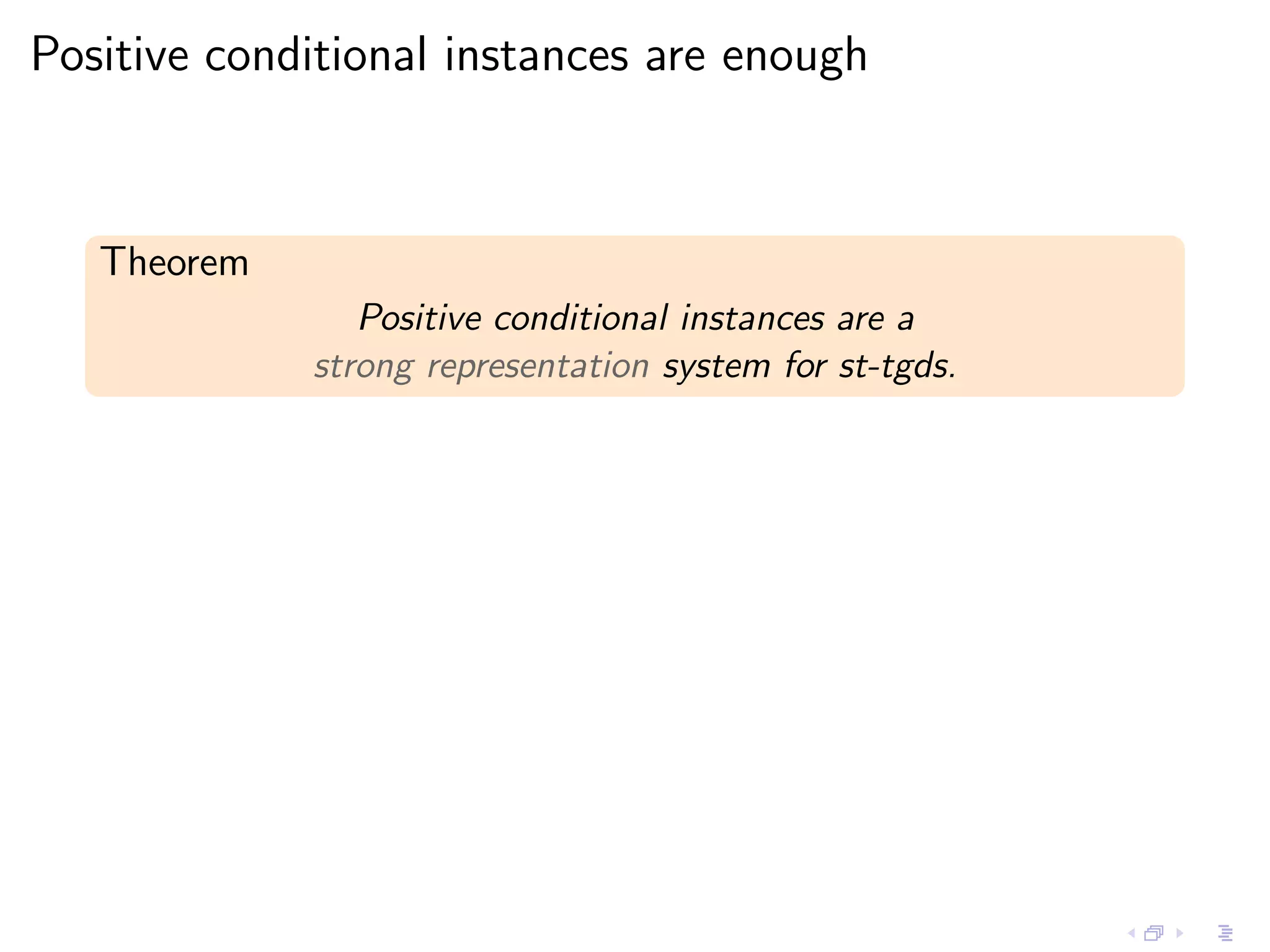

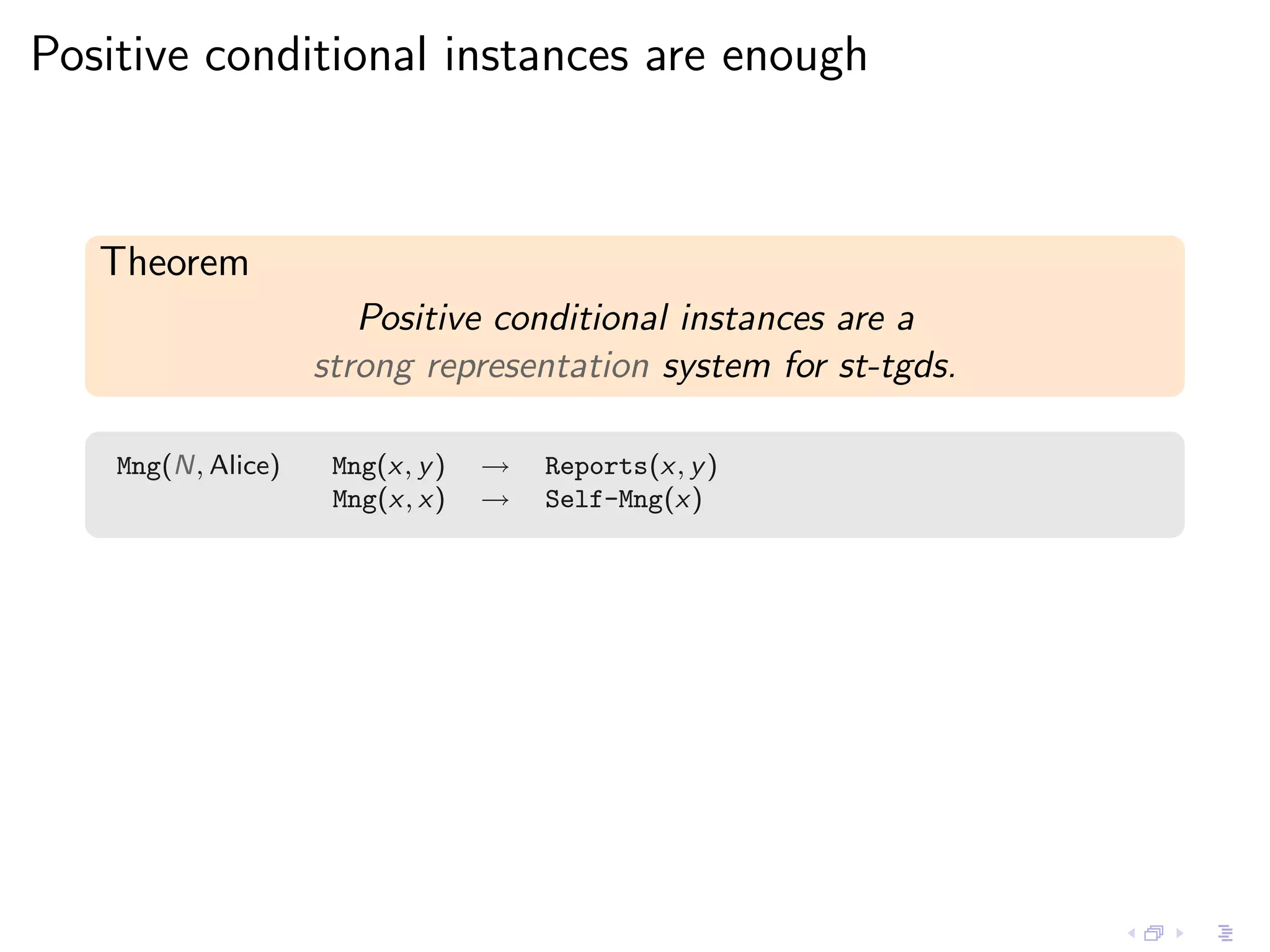

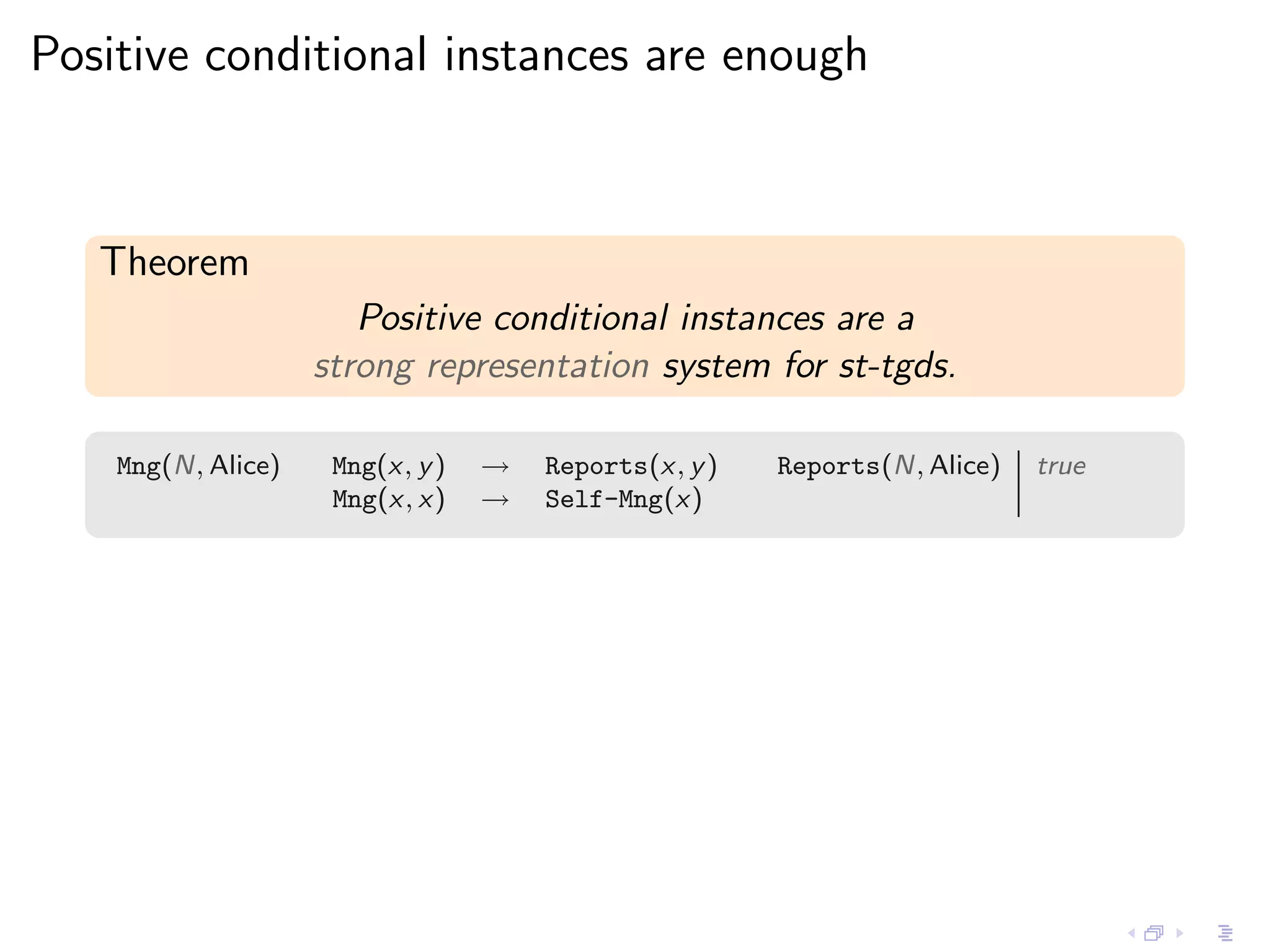

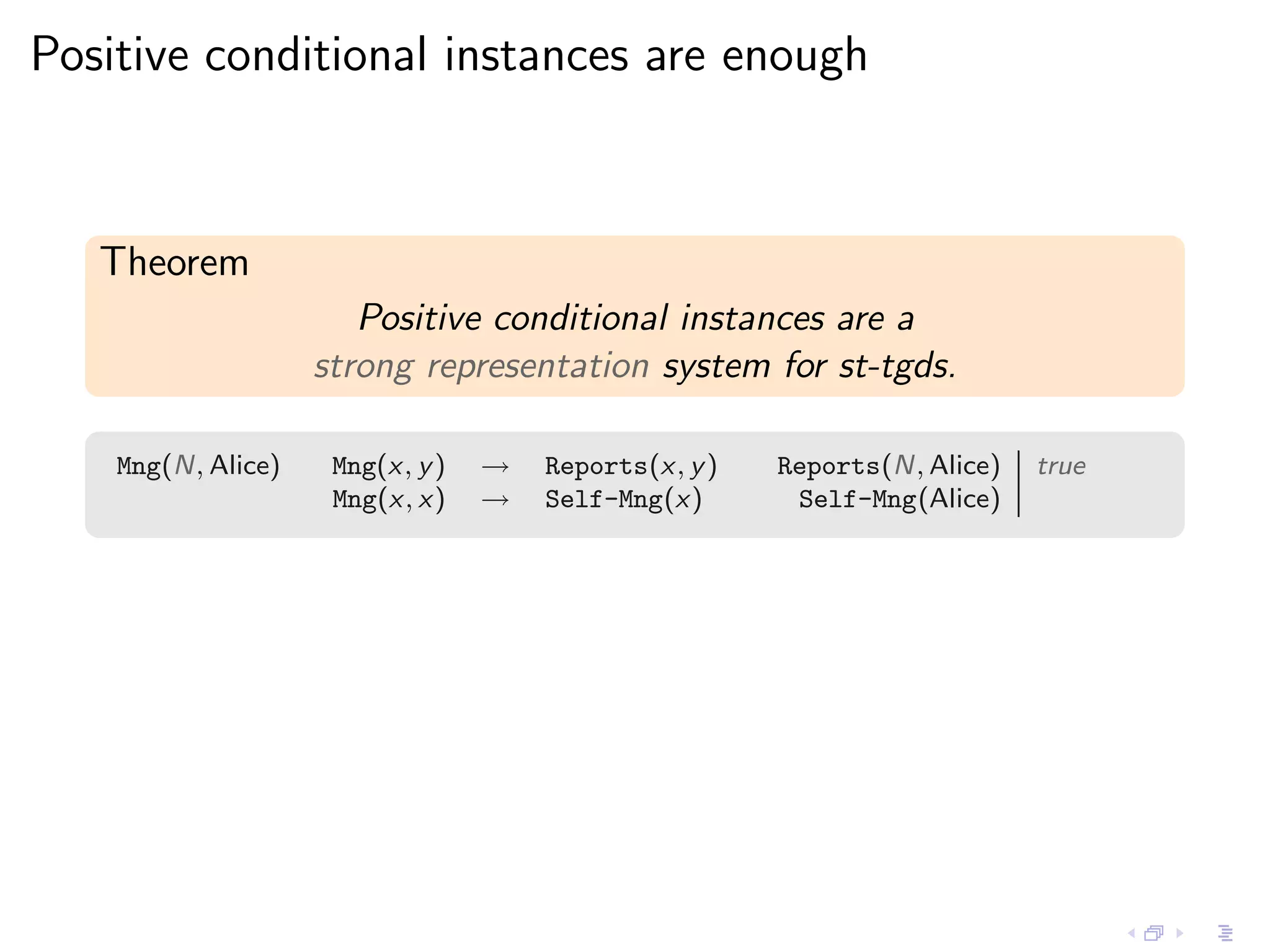

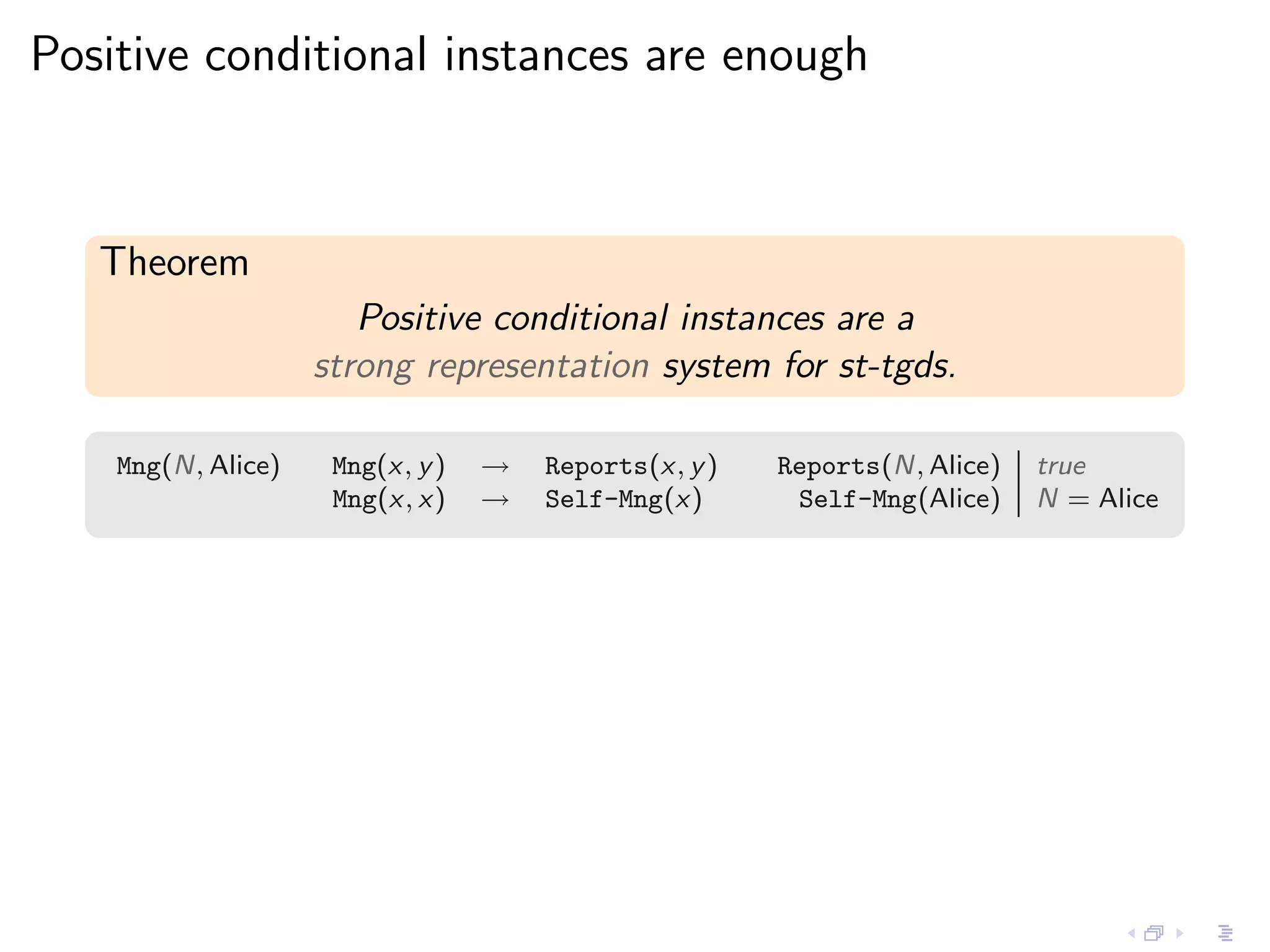

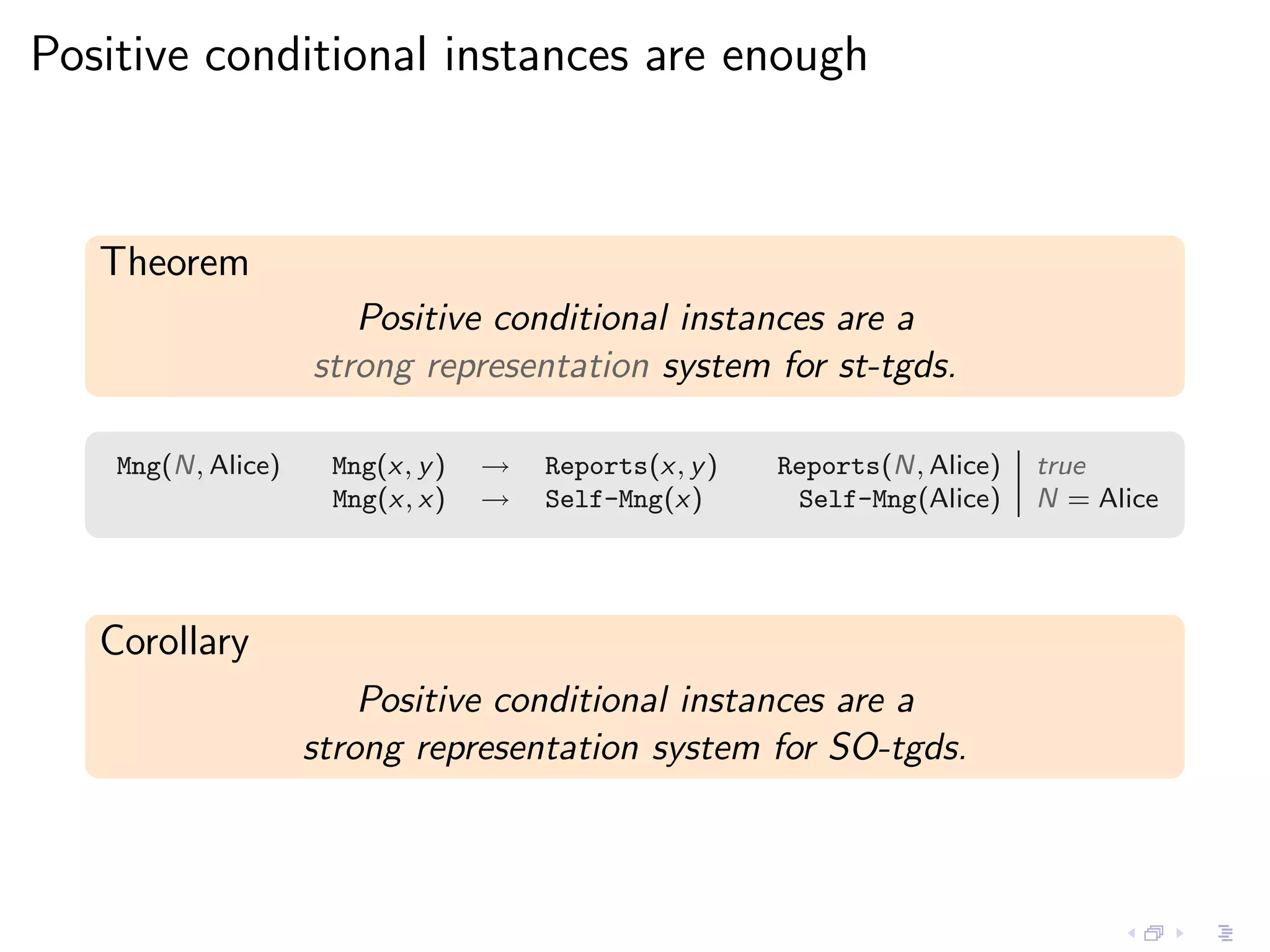

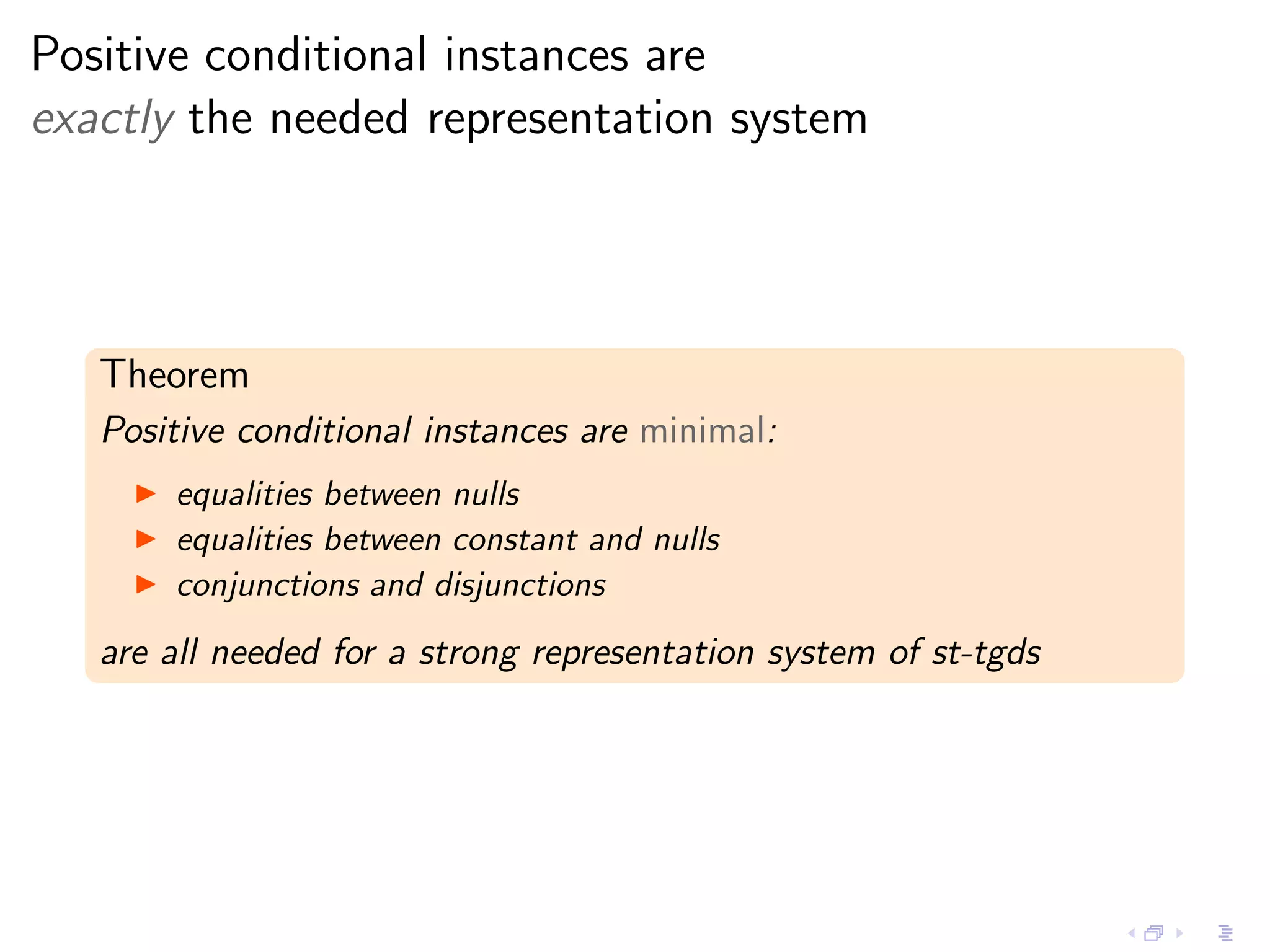

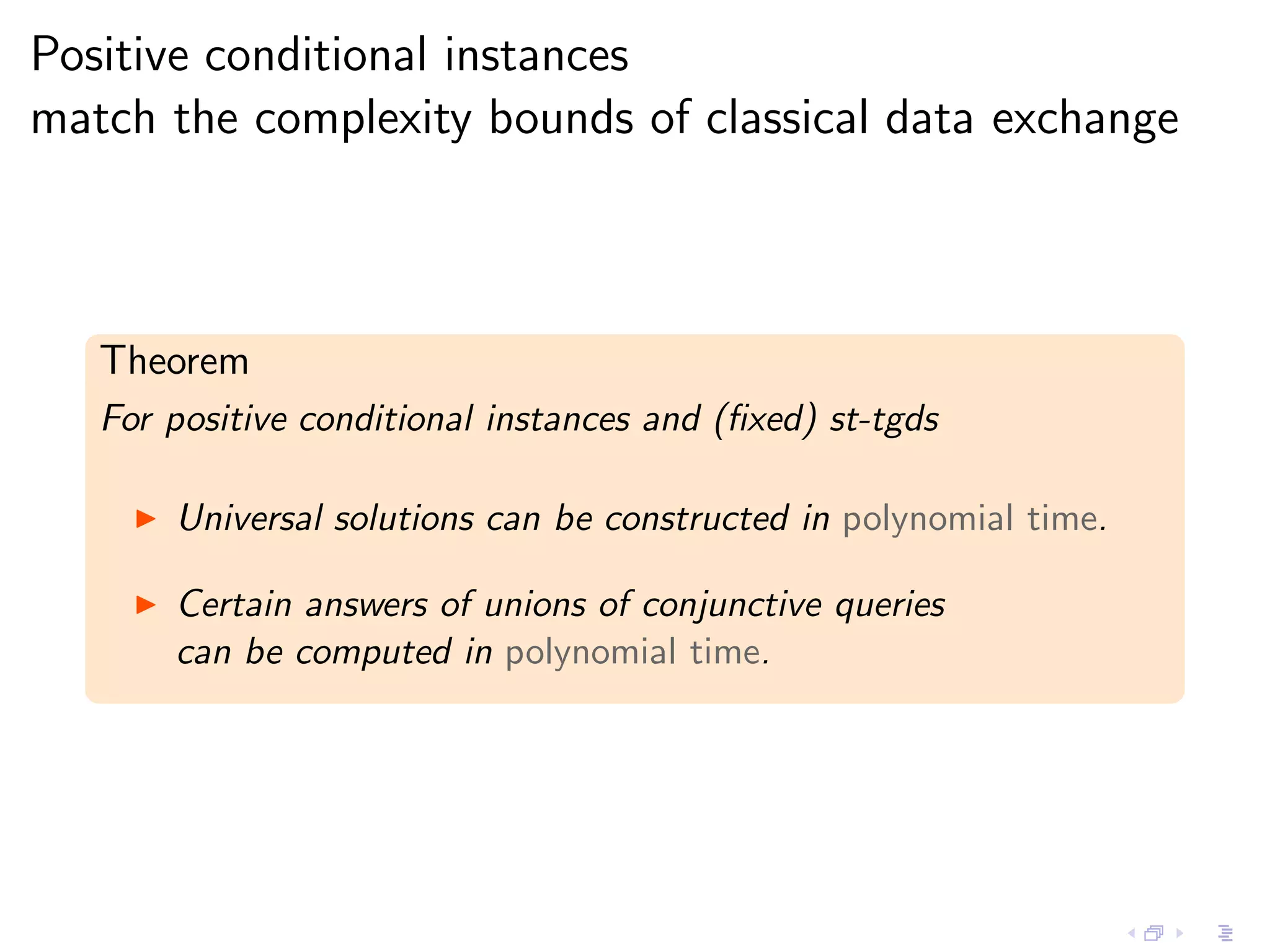

- Incomplete instances like those with null values or constraints can be represented as representation systems, and positive conditional instances form a strong representation system for schema mappings specified by source-to-target tuple-generating dependencies.

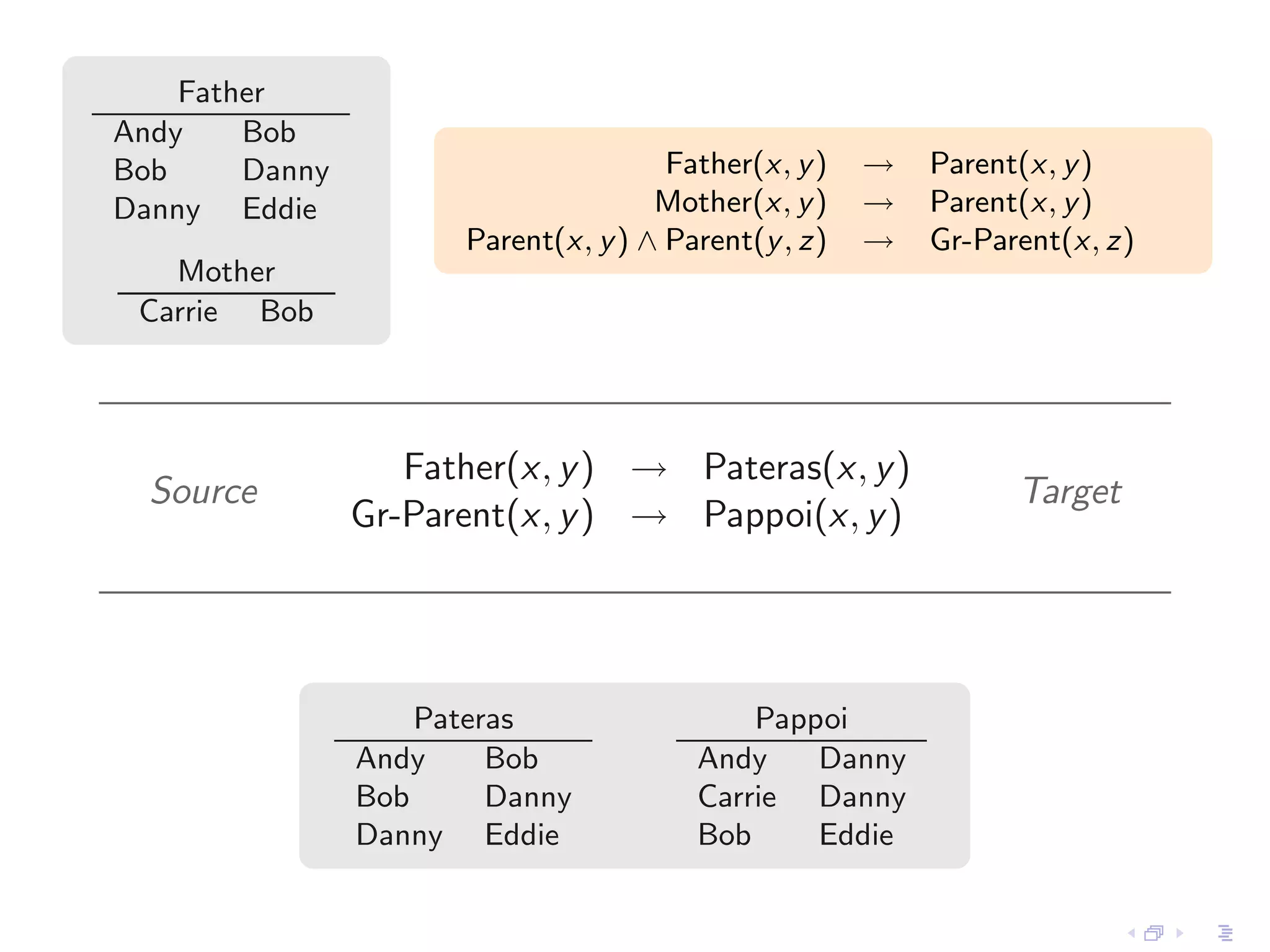

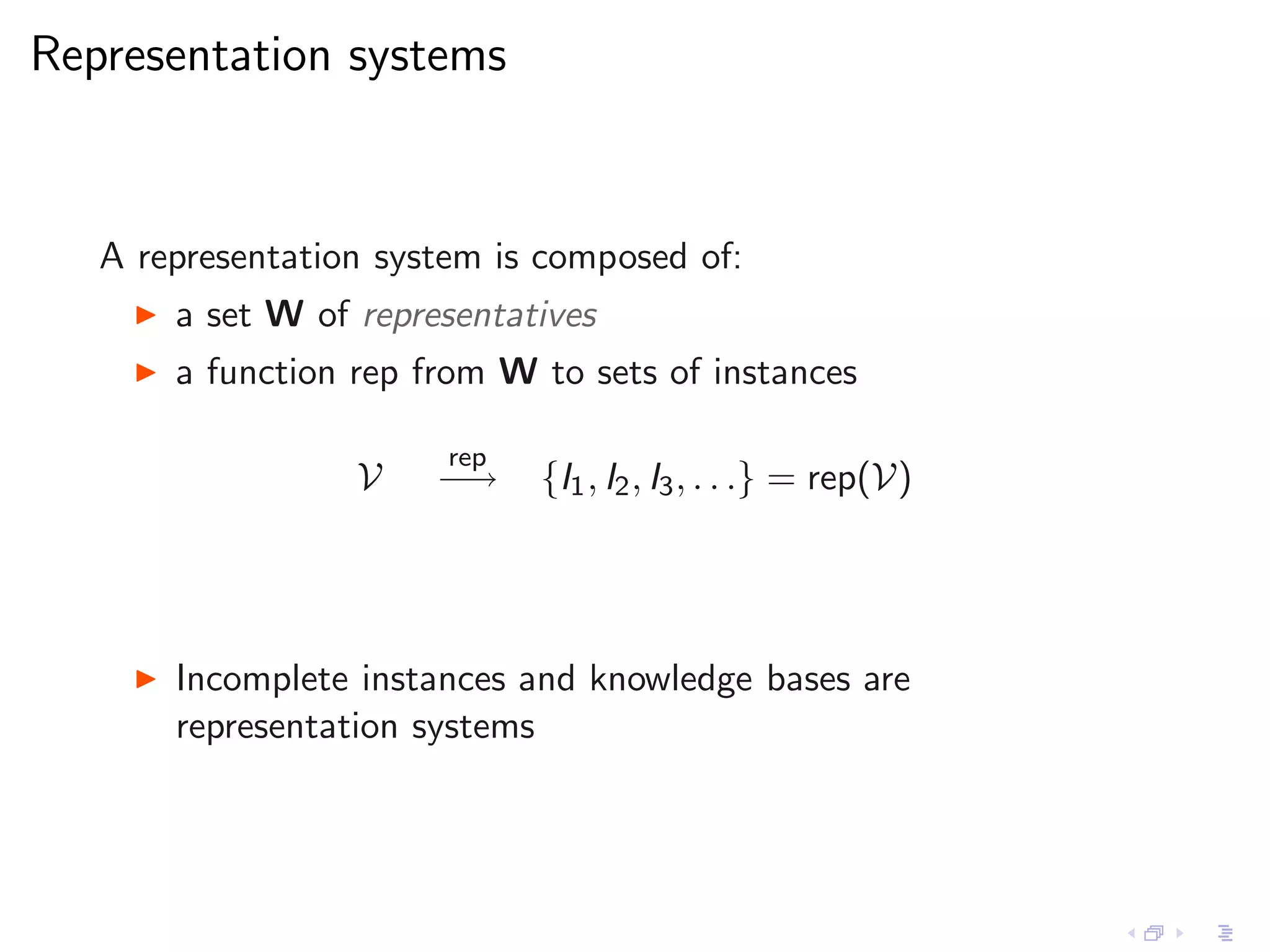

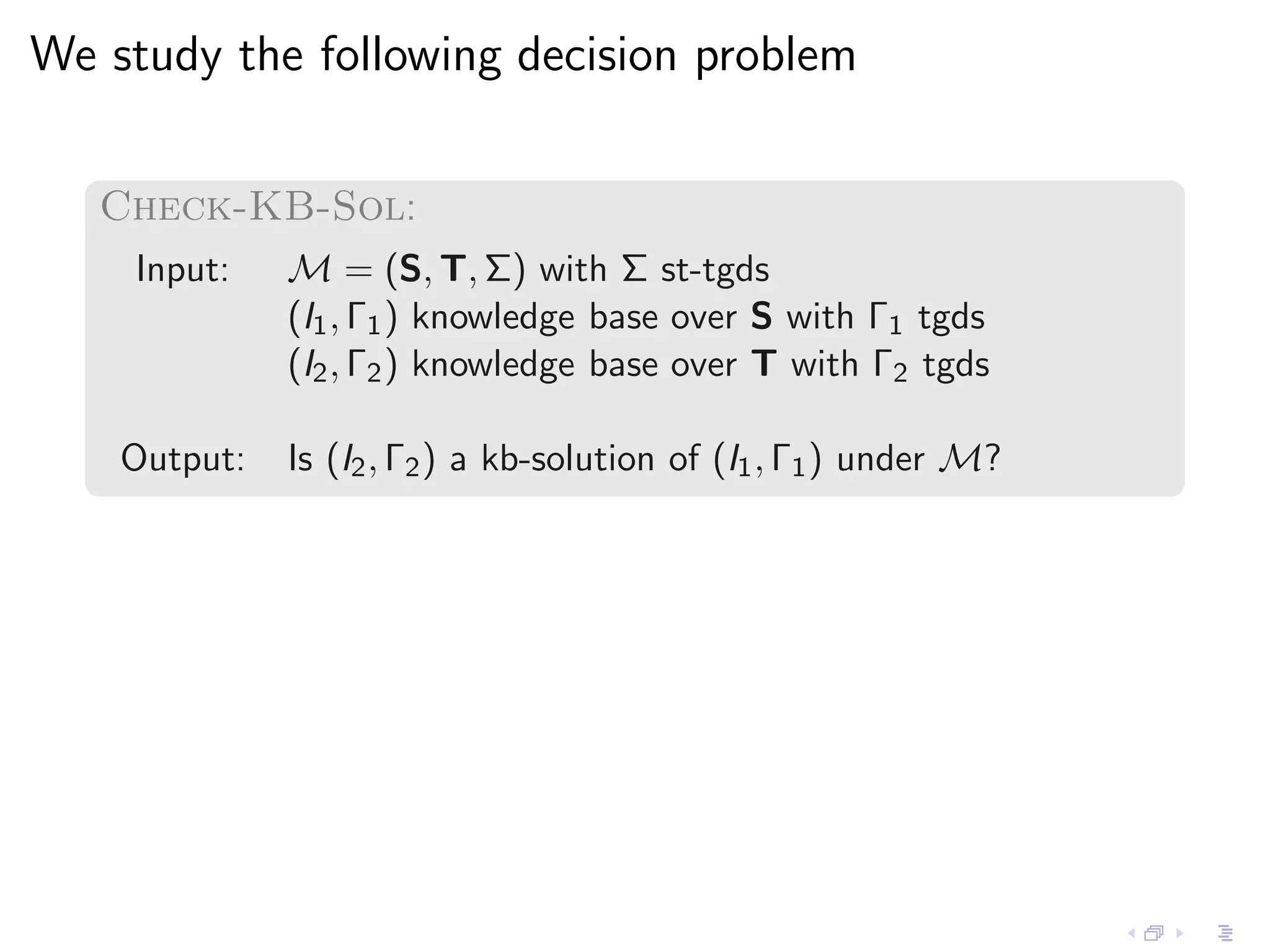

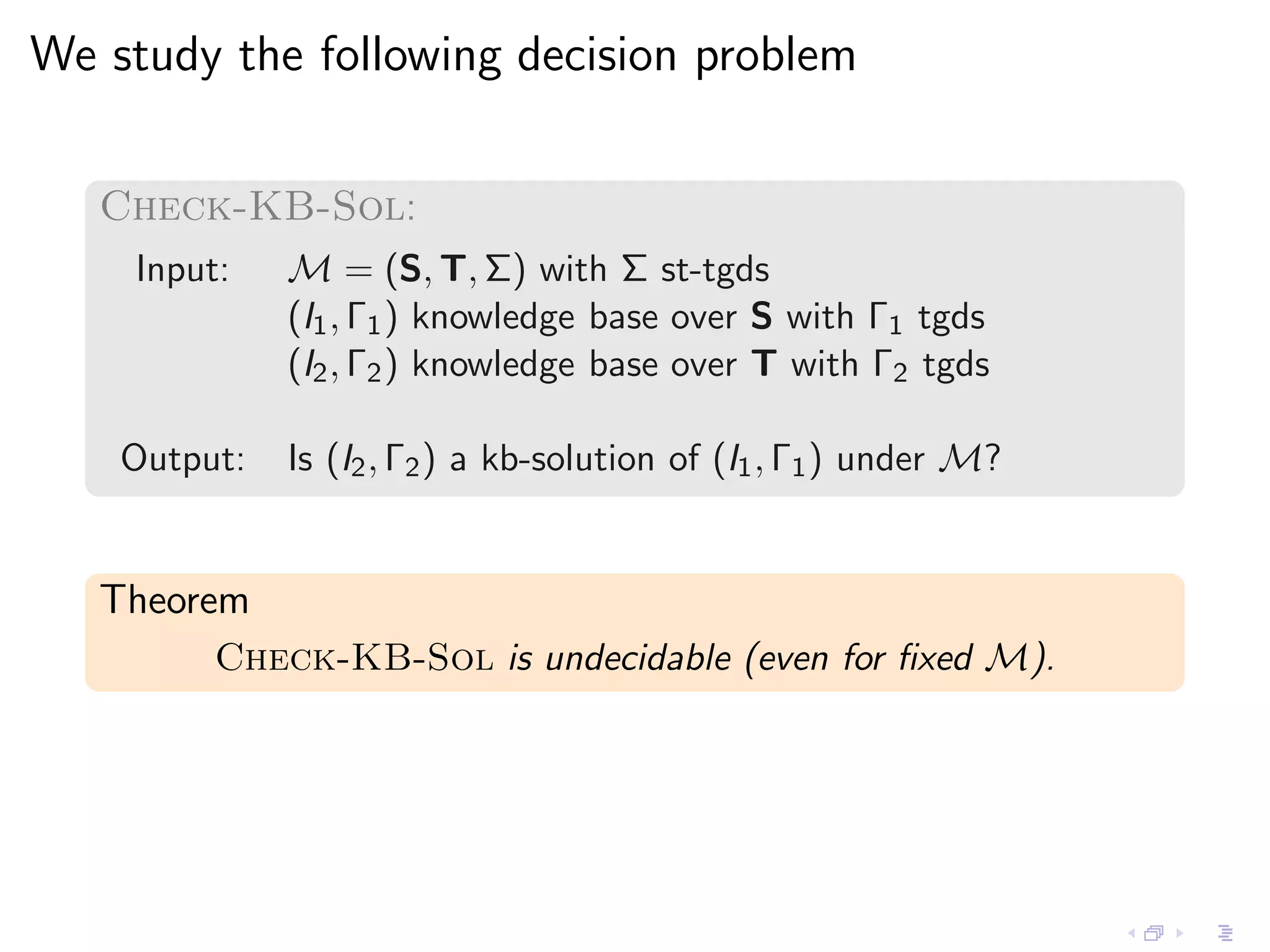

![The complexity of Check-Full-KB-Sol

Theorem

Check-Full-KB-Sol is EXPTIME-complete.

Theorem

If M = (S, T, Σ) is fixed

Check-Full-KB-Sol is ∆P [O(log n)]-complete.

2

∆P [O(log n)]

2 ≡ P NP with only a logarithmic

number of calls to the NP oracle.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20110630-jorgeperez-tuwien-slides-120221074600-phpapp02/75/Exchanging-More-than-Complete-Data-44-2048.jpg)

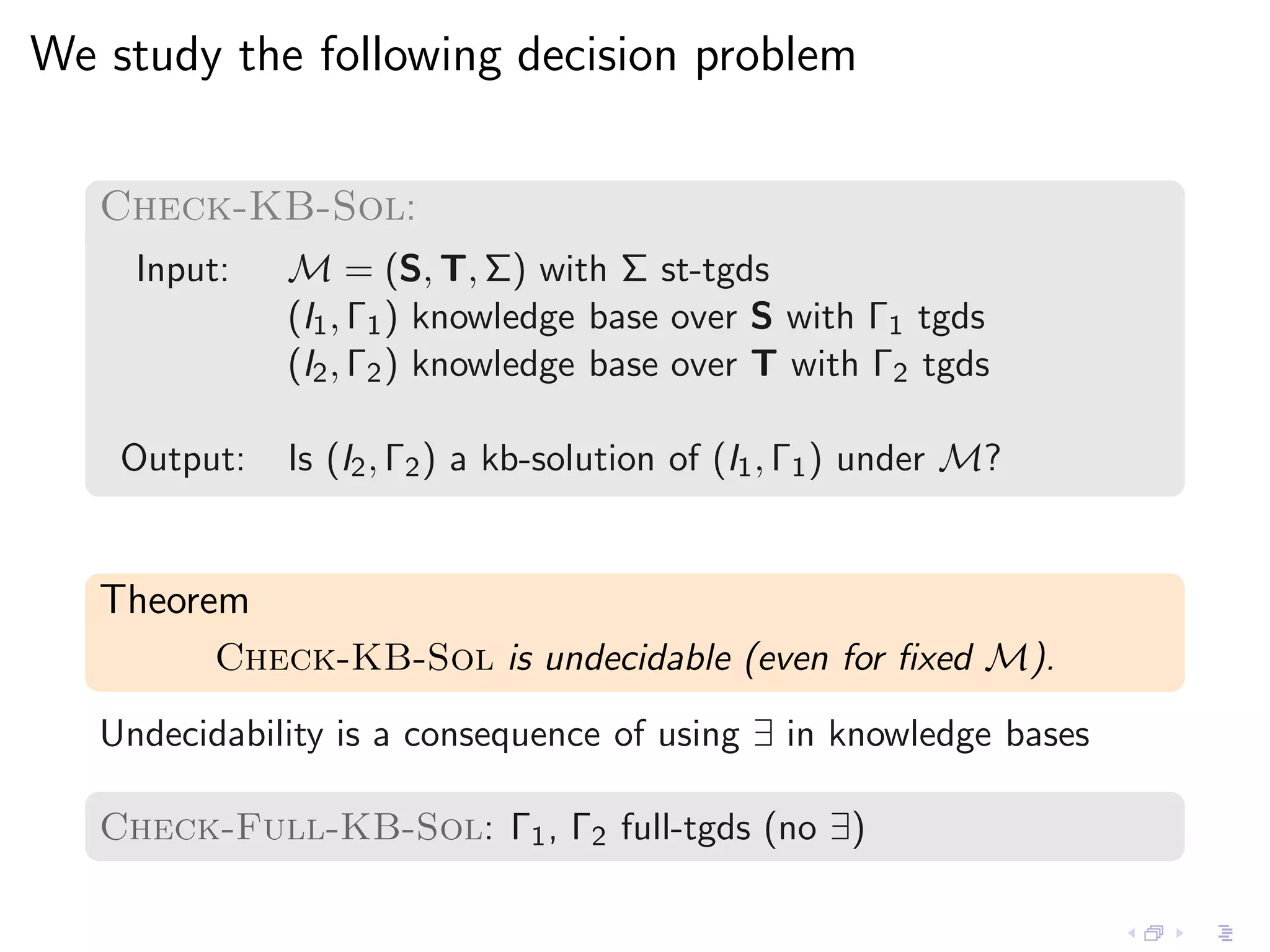

![Hardness is obtained by reducing

the Max-Odd-Clique problem

Given a graph G with n nodes:

S: E (·, ·), Succ(·, ·), Clique(·)

T: E ′ (·, ·), Succ ′ (·, ·), Clique ′ (·)

I1 and I2 are copies of G , plus a successor relation over [1, n]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20110630-jorgeperez-tuwien-slides-120221074600-phpapp02/75/Exchanging-More-than-Complete-Data-47-2048.jpg)

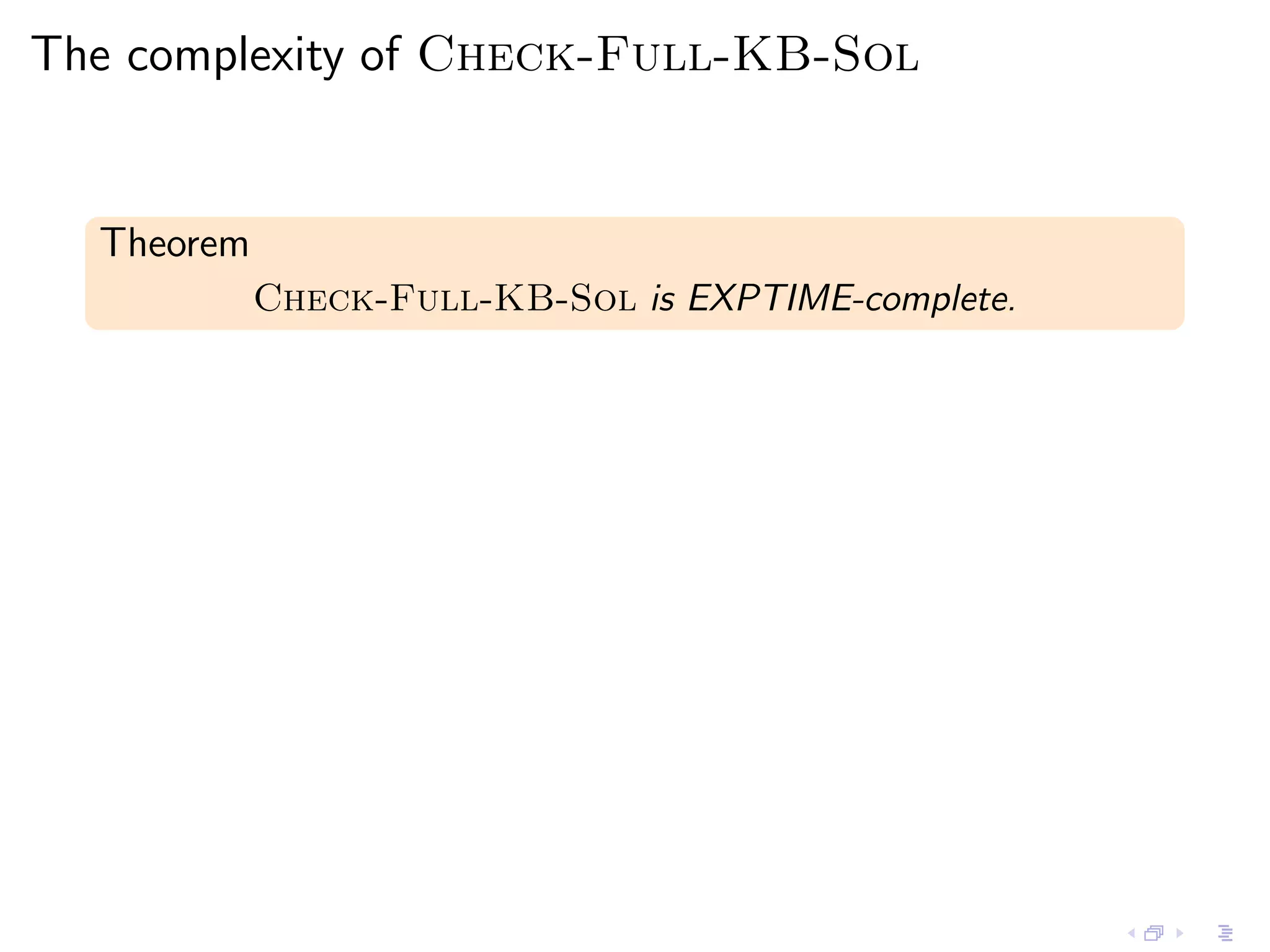

![Hardness is obtained by reducing

the Max-Odd-Clique problem

Given a graph G with n nodes:

S: E (·, ·), Succ(·, ·), Clique(·)

T: E ′ (·, ·), Succ ′ (·, ·), Clique ′ (·)

I1 and I2 are copies of G , plus a successor relation over [1, n]

Γ1 : “E has a clique of even size x ≤ n” → Clique(x)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20110630-jorgeperez-tuwien-slides-120221074600-phpapp02/75/Exchanging-More-than-Complete-Data-48-2048.jpg)

![Hardness is obtained by reducing

the Max-Odd-Clique problem

Given a graph G with n nodes:

S: E (·, ·), Succ(·, ·), Clique(·)

T: E ′ (·, ·), Succ ′ (·, ·), Clique ′ (·)

I1 and I2 are copies of G , plus a successor relation over [1, n]

Γ1 : “E has a clique of even size x ≤ n” → Clique(x)

Γ2 : “E ′ has a clique of odd size x ≤ n” → Clique ′ (x)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20110630-jorgeperez-tuwien-slides-120221074600-phpapp02/75/Exchanging-More-than-Complete-Data-49-2048.jpg)

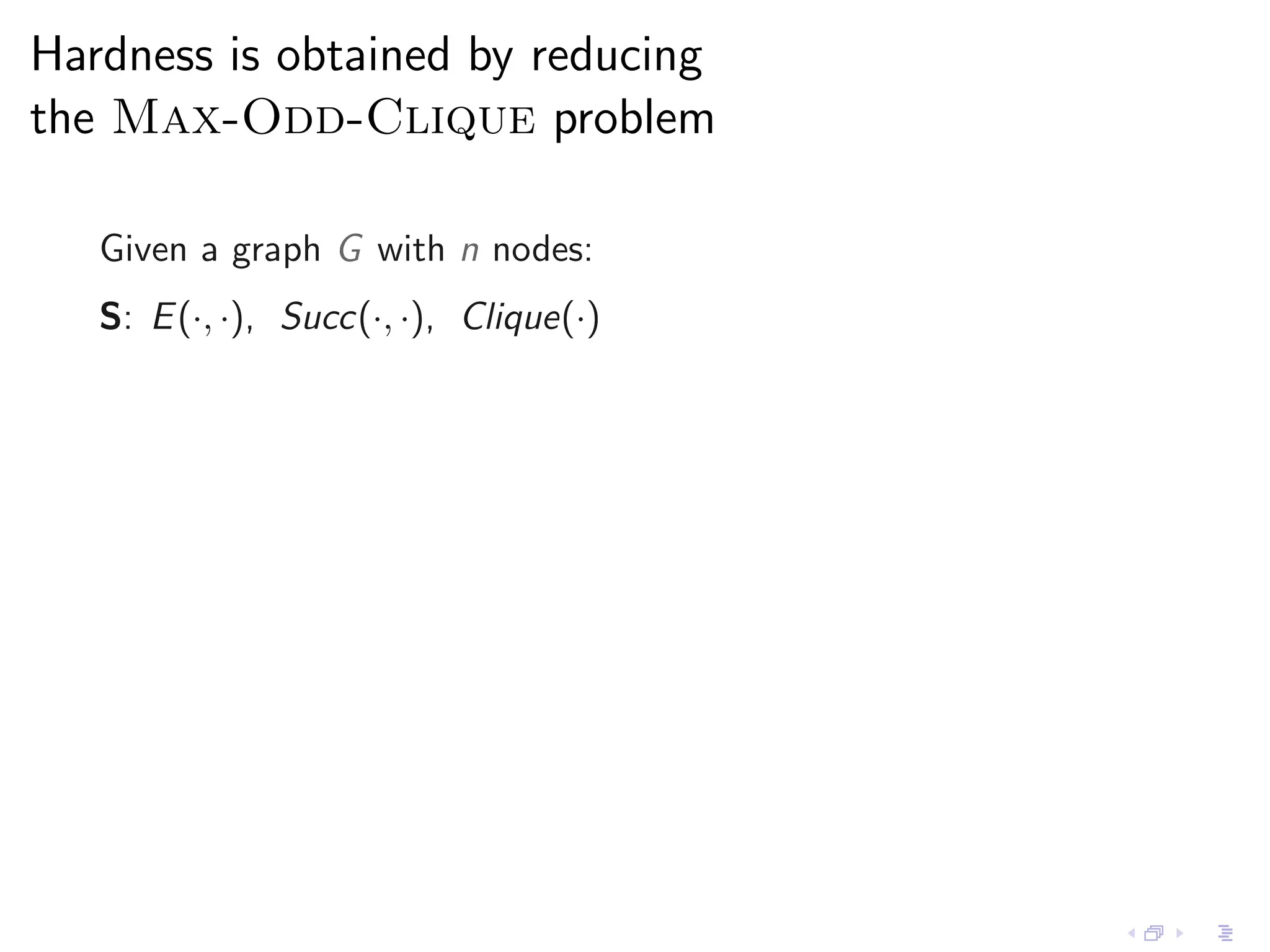

![Hardness is obtained by reducing

the Max-Odd-Clique problem

Given a graph G with n nodes:

S: E (·, ·), Succ(·, ·), Clique(·)

T: E ′ (·, ·), Succ ′ (·, ·), Clique ′ (·)

I1 and I2 are copies of G , plus a successor relation over [1, n]

Γ1 : “E has a clique of even size x ≤ n” → Clique(x)

Γ2 : “E ′ has a clique of odd size x ≤ n” → Clique ′ (x)

Σ: Clique(x) ∧ Succ(x, y ) → Clique ′ (y )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20110630-jorgeperez-tuwien-slides-120221074600-phpapp02/75/Exchanging-More-than-Complete-Data-50-2048.jpg)

![Hardness is obtained by reducing

the Max-Odd-Clique problem

Given a graph G with n nodes:

S: E (·, ·), Succ(·, ·), Clique(·)

T: E ′ (·, ·), Succ ′ (·, ·), Clique ′ (·)

I1 and I2 are copies of G , plus a successor relation over [1, n]

Γ1 : “E has a clique of even size x ≤ n” → Clique(x)

Γ2 : “E ′ has a clique of odd size x ≤ n” → Clique ′ (x)

Σ: Clique(x) ∧ Succ(x, y ) → Clique ′ (y )

(I2 , Γ2 ) is a kb-solution of (I1 , Σ1 ) iff

the maximum size of a clique in G is odd.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20110630-jorgeperez-tuwien-slides-120221074600-phpapp02/75/Exchanging-More-than-Complete-Data-51-2048.jpg)