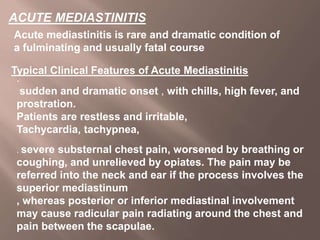

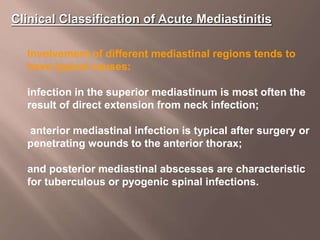

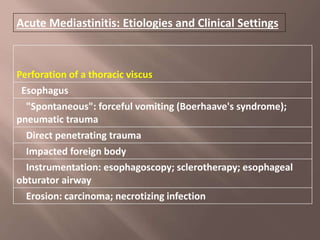

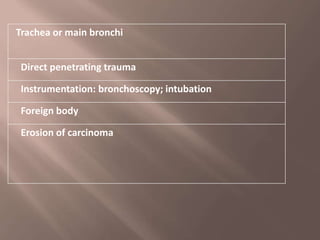

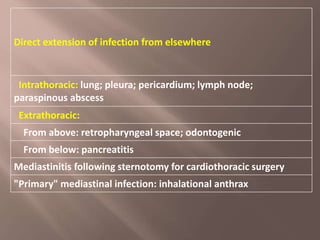

1. Acute mediastinitis is a rare and serious condition caused by infection or perforation spreading to the mediastinum. It commonly arises from infection of the esophagus, trachea, or other structures directly above or below the mediastinum.

2. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis occurs when an oropharyngeal infection, such as a dental infection, spreads downward through neck spaces into the mediastinum. Mediastinitis can also develop after cardiac surgery when infection spreads from the sternum.

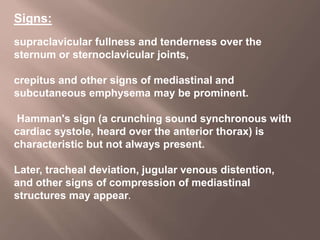

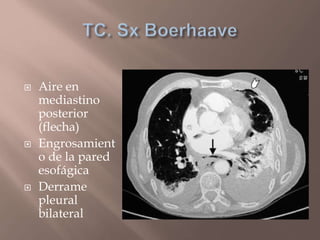

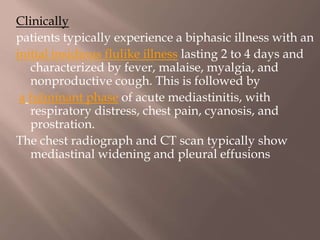

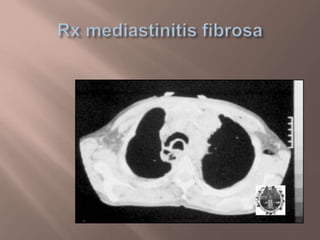

3. Symptoms include chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. Diagnosis is suggested by chest x-ray or CT scan showing air or fluid in the