1) The document discusses methods for visual localization and texture categorization using interest point detection and entropy saliency. It focuses on using scale-space analysis and learning distributions to filter out less salient regions for computational efficiency.

2) An entropy saliency detector is proposed that uses local entropy calculations at multiple scales to identify salient regions. Scale-space analysis allows detection of salient regions without prior knowledge of scale.

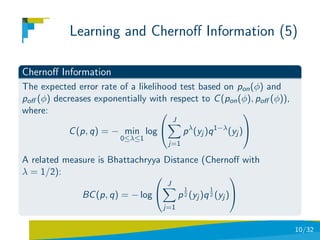

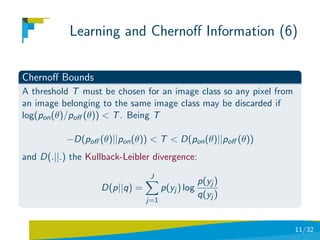

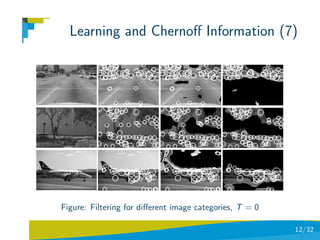

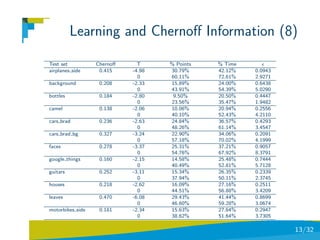

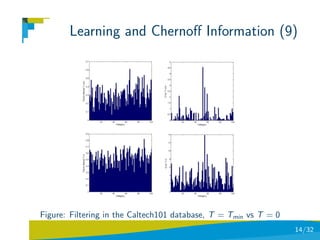

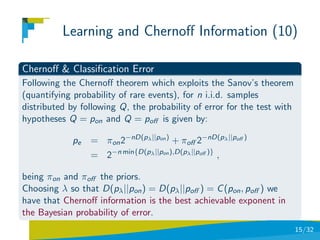

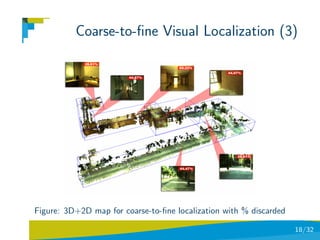

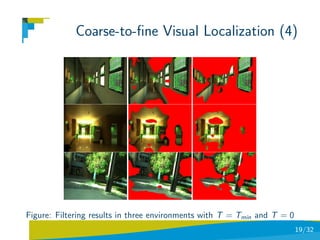

3) Techniques including Chernoff information and Kullback-Leibler divergence are discussed for learning distributions of image categories and defining thresholds to filter regions, reducing computational costs of interest point detection and description.

![Interest Points

Background.From the classical Harris detector, a big bang of

interest-point detectors ensuring some sort of invariance to

zoom/scale, rotation and perspective distortion has emerged since

the proposal of SIFT detector and descriptors [Lowe,04].

These detectors, typically including a multi-scale analysis of the

image, include Harris Affine, MSER [Matas et al,02] and SURF [Bay

et al,08].The need of an intensive comparison of different detectors

(and descriptors) mainly in terms of spatio-temporal stability

(repeatability, distinctiveness and robustness) is yet a classic

challenge [Mikolajczyk et al, 05].

Stability experiments are key to predict the future behavior of the

dectector/descriptor in subsequent tasks (bag-of-words recognition,

matching,...)

2/32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2interest-pointscvpr-110515221933-phpapp02/85/CVPR2010-Advanced-ITinCVPR-in-a-Nutshell-part-2-Interest-Points-2-320.jpg)

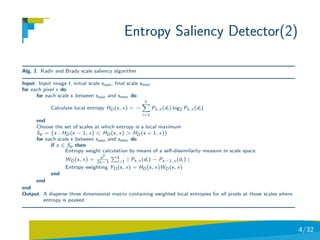

![Entropy Saliency Detector

Local Saliency, in contrast to global one [Ullman, 96], means local

distinctiveness (outstanding/popout pixel distributions over the

image) [Julesz,81][Nothdurft,00].

In Computer Vision, a mild IT definition of local saliency is linked to

visual unpredictability [Kadir and Brady,01]. Then a salient region is

locally unpredictible (measured by entropy) and this is consistent

with a peak of entropy in scale-space.

Scale-space analysis is key because we do not know the scale of

regions beforehand. In addition, isotropic detections may be

extended to affine detectors with an extra computational cost. (see

Alg. 1).

3/32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2interest-pointscvpr-110515221933-phpapp02/85/CVPR2010-Advanced-ITinCVPR-in-a-Nutshell-part-2-Interest-Points-3-320.jpg)

![Learning and Chernoff Information

Scale-space analysis, is, thus, one of the bottlenecks of the process.

However, having a prior knowledge of the statistics of the images

being analyzed it is possible to discard a significant number of

pixels, and thus, avoid scale-space analysis.

Working hypothesis

If the local distribution around a pixel at a scale smax is highly

homogeneous (low entropy) one may assume that for scales

s < smax it will happen the same. Thus, scale-space peaks will not

exist in this range of scales.[Suau and Escolano,08].

Inspired in statistical detection of edges [Konishi et al.,03] and

contours [Cazorla & Escolano, 03] and also in contour grouping

[Cazorla et al.,02].

6/32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2interest-pointscvpr-110515221933-phpapp02/85/CVPR2010-Advanced-ITinCVPR-in-a-Nutshell-part-2-Interest-Points-6-320.jpg)

![Learning and Chernoff Information(2)

Relative entropy and threshold, a basic procedure consists of

computing the ratio between the entropy at smax and the maximum

of entropies for all pixels at their smax

Filtering by homogeneity along scale-space

1. Calculate the local entropy HD for each pixel at scale smax .

2. Select an entropy threshold σ ∈ [0, 1].

HD (x,smax )

3. X = {x | maxx {HD (x,smax )} > σ}

4. Apply scale saliency algorithm only to those pixels x ∈ X .

What is the optimal threshold σ?

7/32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2interest-pointscvpr-110515221933-phpapp02/85/CVPR2010-Advanced-ITinCVPR-in-a-Nutshell-part-2-Interest-Points-7-320.jpg)

![Coarse-to-fine Visual Localization

Problem Statement

A 6DOF SLAM method has built a 3D+2D map of an

indoor/outdoor environment [Lozano et al, 09].

We have manually marked 6 environments and trained a

minimal complexity supervised classifier (see next lesson) for

performing coarse localization.

We got the statistics from the images of each environment in

order to infer their respective pon and poff distributions and

hence their Chernoff information and T bounds.

Once a test image is submitted it is classified and filtered

according to Chernoff information. Then the keypoints are

computed.

16/32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2interest-pointscvpr-110515221933-phpapp02/85/CVPR2010-Advanced-ITinCVPR-in-a-Nutshell-part-2-Interest-Points-16-320.jpg)

![Coarse-to-fine Visual Localization (2)

Problem Statement (cont)

Using the SIFT descriptors of the keypoints and the GTM

algorithm [Aguilar et al, 09] we match the image with a

structural + appearance prototype previously unsupervisedly

learned through an EM-algorithm.

The prototype tells us what is the sub-environment to which

the image belongs.

In order to perform fine localization we match the image with

the structure and appearance off all images assigned to a given

sub-enviromnent and then select the one with highest

likelihood.

See more in the Feature-selection lesson.

17/32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2interest-pointscvpr-110515221933-phpapp02/85/CVPR2010-Advanced-ITinCVPR-in-a-Nutshell-part-2-Interest-Points-17-320.jpg)

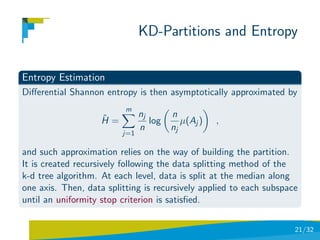

![KD-Partitions and Entropy

Data Partitions and Density Estimation

Let X be a d-dimensional random variable, and f (x) its pdf. Let

A = {Aj |j = 1, . . . , m} be a partition of X for which Ai ∩ Aj = ∅ if

i = j and j Aj = X . Then, we have [Stowell& Plumbley, 09]:

Aj f (x) nj

fAj = ˆ

fAj (x) = ,

µ(Aj ) nµ(Aj )

where fAj approximates f (x) in each cell, µ(Aj ) is the d-dimensional

volume of Aj . If f (x) is unknown and we are given a set of samples

X = {x1 , . . . , xn } from it, being xi ∈ Rd , we can approximate the

probability of f (x) in each cell as pj = nj /n, where nj is the number

of samples in cell Aj .

20/32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2interest-pointscvpr-110515221933-phpapp02/85/CVPR2010-Advanced-ITinCVPR-in-a-Nutshell-part-2-Interest-Points-20-320.jpg)

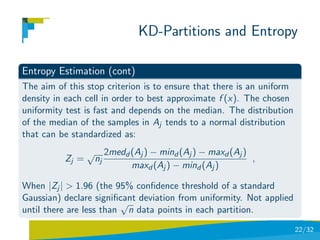

![KD-Partitions and Divergence

KDP Total-Variation Divergence

The total variation distance [Denuit and Bellegem,01] between two

probability measures P and Q for a finite alphabet, is given by:

1

δ(P, Q) = |P(x) − Q(x)| .

2 x

Then, the divergence is simply formulated as:

p

1 nx,j no,j

δ(P, Q) = |pj −qj | ∈ [0, 1], p(Aj ) = = pj p(Aj ) = = qj

2 nx no

j=1

where pi and pj are the proportion of samples of P and Q in cell Aj .

23/32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2interest-pointscvpr-110515221933-phpapp02/85/CVPR2010-Advanced-ITinCVPR-in-a-Nutshell-part-2-Interest-Points-23-320.jpg)

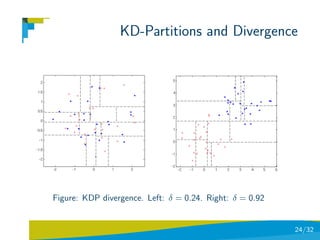

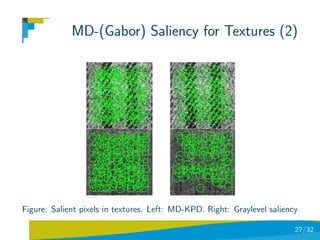

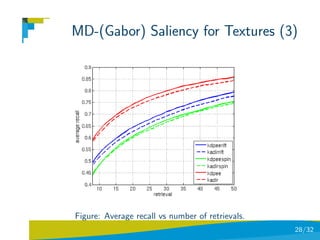

![MD-(Gabor) Saliency for Textures

KDP Total-Variation Divergence

Use Brodatz dataset (111 textures and 9 images per category:

999 images).

Use 15 Gabor filters for obtaining multi-dimensional data.

Both graylevel saliency and MD saliency are tuned to obtain

150 salient points.

Use each image in the database as query image.

Use: saliency with only RIFT, only spin images, and combining

RIFT and spin images.

retrieval-recall results strongly influenced by the type of

descriptor used [Suau & Escolano,10].

26/32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2interest-pointscvpr-110515221933-phpapp02/85/CVPR2010-Advanced-ITinCVPR-in-a-Nutshell-part-2-Interest-Points-26-320.jpg)

![References

[Lowe,04] Lowe, D. (2004). Distinctive image features from scale

invariant keypoints. International Journal of Computer Vision,

60(2):91–110

[Matas et al,02] Matas, J., Chum, O., Urban, M., and Pajdla, T.

(2004). Ro- bust wide baseline stereo from maximally stable extremal

regions. Image and Vision Computing, 22(10):761–767

[Mikolajczyk et al, 05] Mikolajczyk, K., Tuytelaars, T., Schmid, C.,

Zisserman, A., Matas, J., Schaffalitzky, F., Kadir, T., and Gool, L. V.

(2005). A comparison of afne region detectors. International Journal

of Computer Vision, 65(1/2):43–72

[Ullman,96] High-level Vision, MIT Press, 1996

29/32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2interest-pointscvpr-110515221933-phpapp02/85/CVPR2010-Advanced-ITinCVPR-in-a-Nutshell-part-2-Interest-Points-29-320.jpg)

![References (2)

[Julesz,81] Julesz, B. (1981). Textons, the Elements of Texture

Perception, and their Interactions. Nature 290 (5802): 91–97

[Nothdurft,00] Nothdurft, H.C. Salience from feature contrast:

variations with texture density. Vision Research 40 (2000): 3181–3200

[Kadir and Brady,01] Kadir, T. and Brady, M. (2001). Scale, saliency

and image description. International Journal of Computer Vision,

45(2):83–105

[Suau and Escolano,08] Suau, P., Escolano, F. (2008) Bayesian

Optimization of the Scale Saliency Filter. Image and Vision

Computing, 26(9), pp. 1207–1218

30/32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2interest-pointscvpr-110515221933-phpapp02/85/CVPR2010-Advanced-ITinCVPR-in-a-Nutshell-part-2-Interest-Points-30-320.jpg)

![References (3)

[Konishi et al.,03] Konishi, S., Yuille, A. L., Coughlan, J. M., and

Zhu, S. C. (2003). Statistical edge detection: learning and evaluating

edge cues. IEEE Trans. on PAMI, 25(1):57–74

[Cazorla & Escolano] Cazorla, M. and Escolano, F. (2003). Two

Bayesian methods for junction detection. IEEE Transactions on

Image Processing, 12(3):317–327

[Cazorla et al.,02] Cazorla, M., Escolano, F., Gallardo, D., and Rizo,

R. (2002). Junction detection and grouping with probabilistic edge

models and Bayesian A*. Pattern Recognition, 35(9):1869–1881

[Lozano et al, 09] Lozano M,A., Escolano, F., Bonev, B., Suau, P.,

Aguilar, W., S´ez, J.M., Cazorla, M. (2009). Region and constell.

a

based categorization of images with unsupervised graph learning.

Image Vision Comput. 27(7): 960–978

31/32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2interest-pointscvpr-110515221933-phpapp02/85/CVPR2010-Advanced-ITinCVPR-in-a-Nutshell-part-2-Interest-Points-31-320.jpg)

![References (4)

[Aguilar et al, 09] Aguilar, W., Frauel Y., Escolano, F., Martnez-Prez,

M.E., Espinosa-Romero, A., Lozano, M.A. (2009) A robust Graph

Transformation Matching for non-rigid registration. Image Vision

Comput. 27(7): 897–910

[Stowell& Plumbley, 09] Stowell, D. and Plumbley, M. D. (2009).

Fast multidimensional entropy estimation by k-d partitioning. IEEE

Signal Processing Letters, 16(6):537–540

[Suau & Escolano,10] Suau, P., Escolano, F. (2010). Analysis of the

Multi-Dimensional Scale Saliency Algorithm and its Application to

Texture Categorization, SSPR’2010 (accepted)

32/32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2interest-pointscvpr-110515221933-phpapp02/85/CVPR2010-Advanced-ITinCVPR-in-a-Nutshell-part-2-Interest-Points-32-320.jpg)