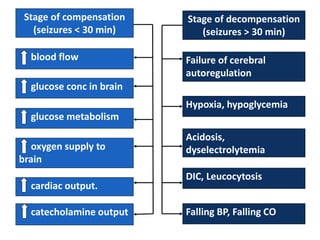

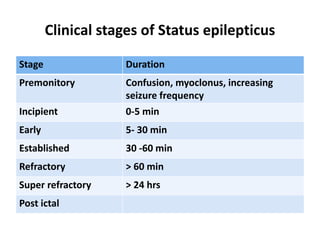

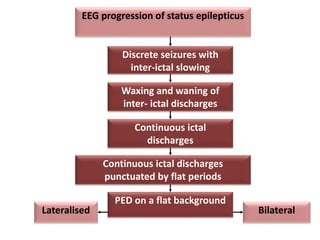

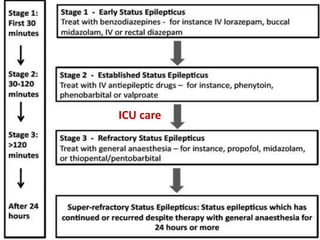

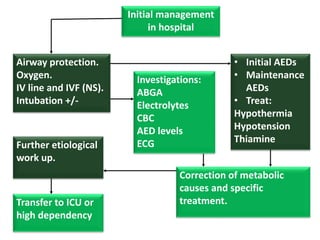

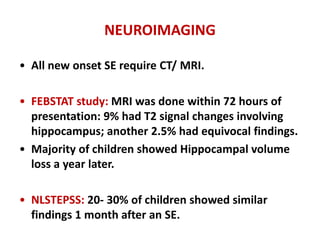

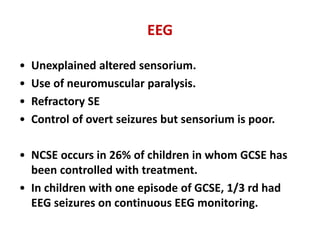

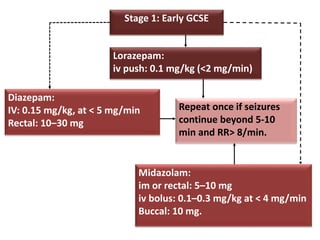

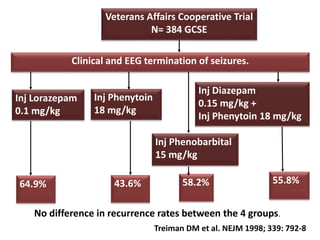

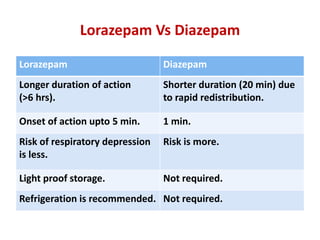

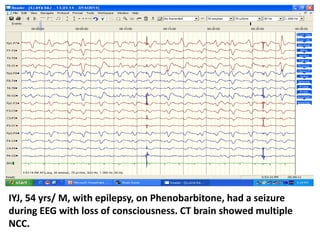

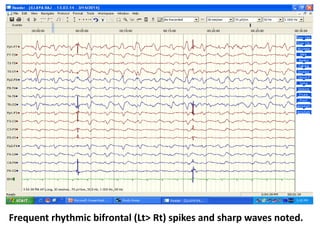

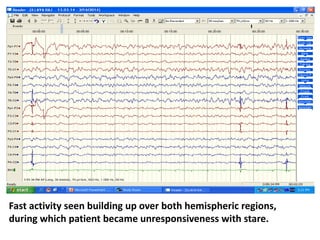

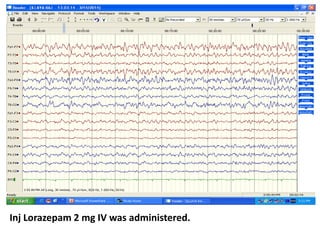

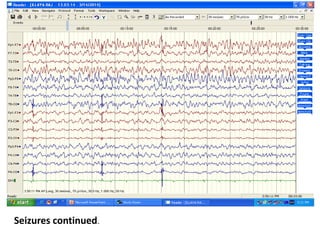

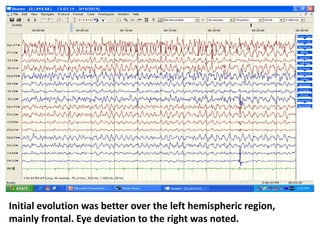

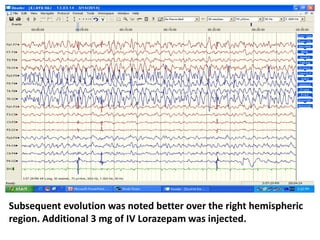

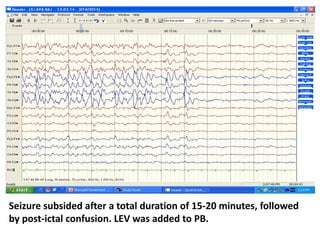

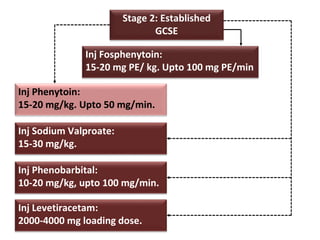

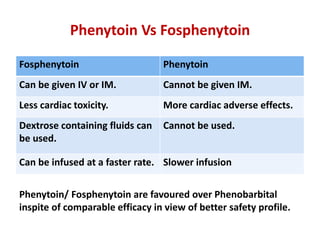

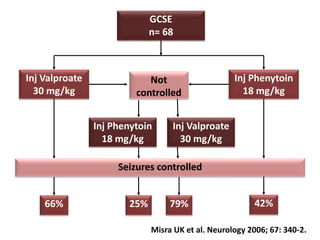

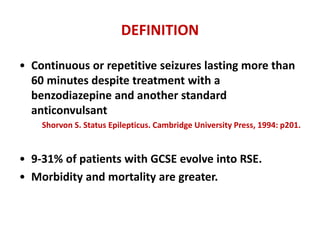

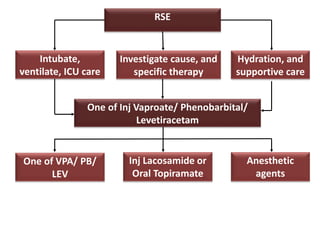

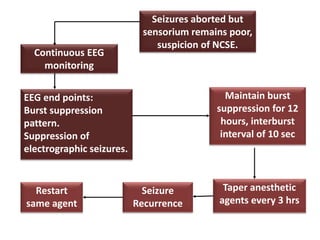

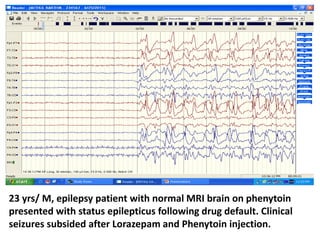

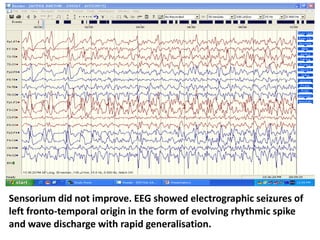

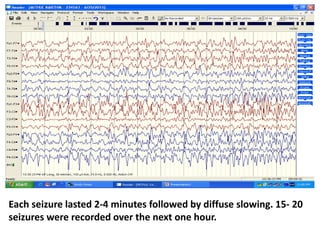

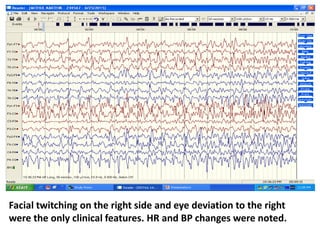

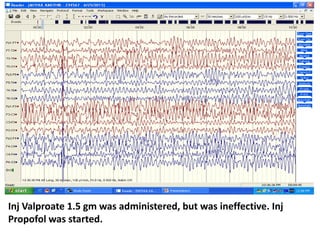

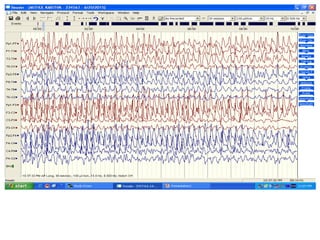

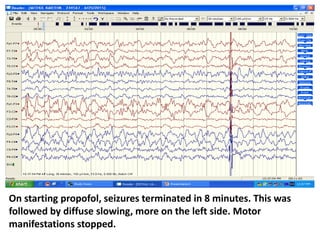

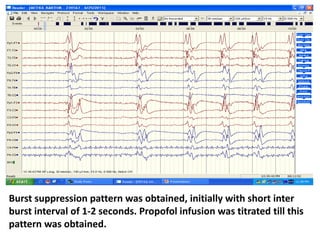

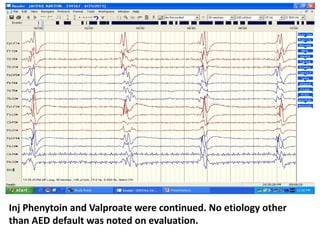

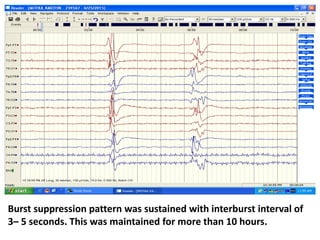

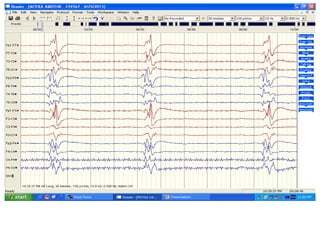

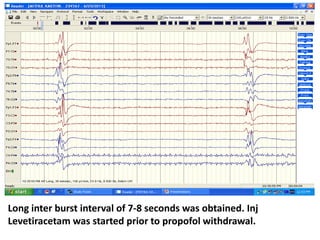

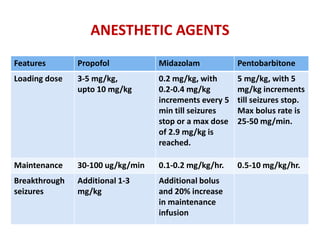

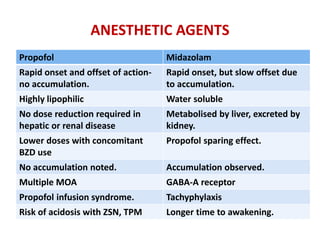

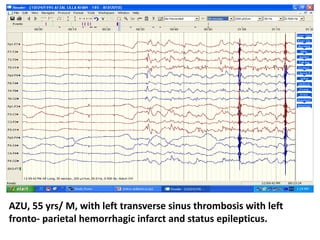

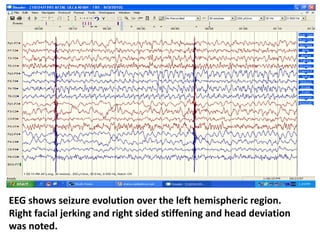

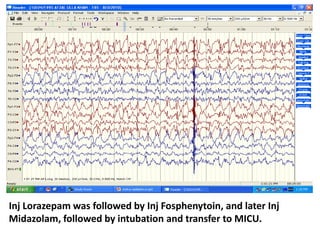

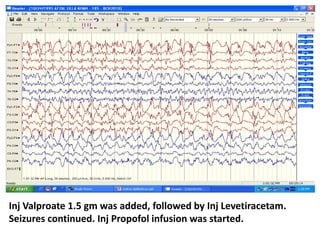

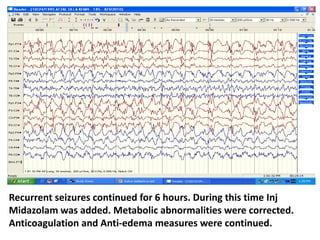

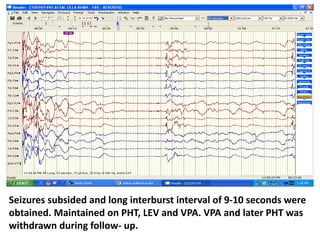

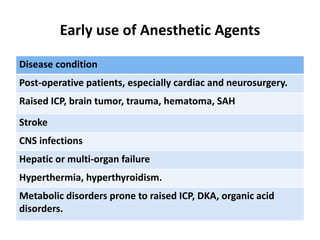

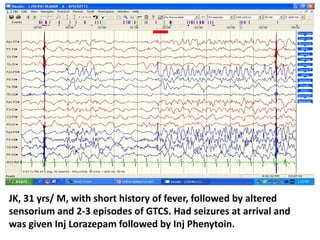

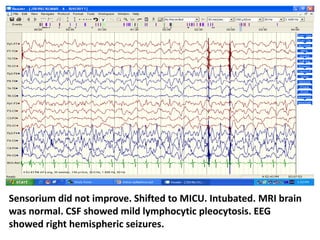

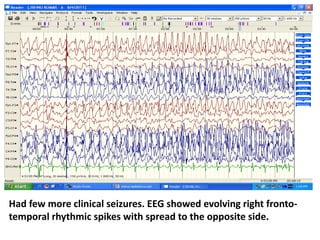

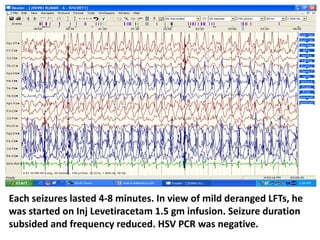

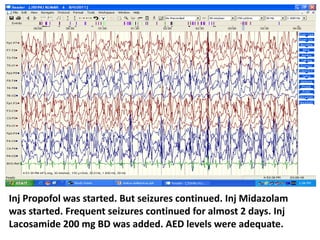

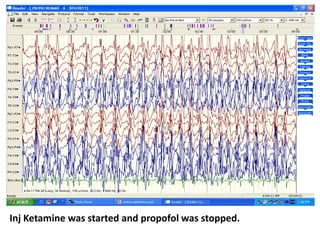

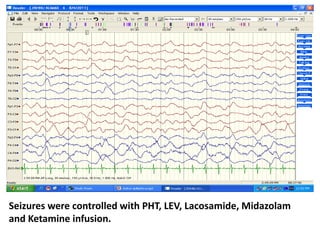

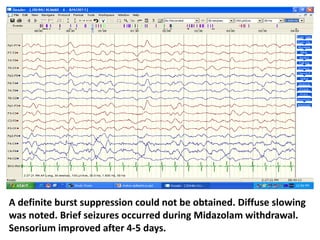

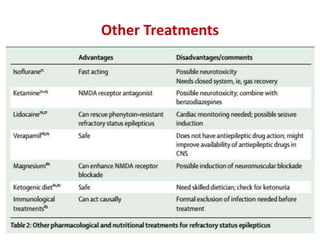

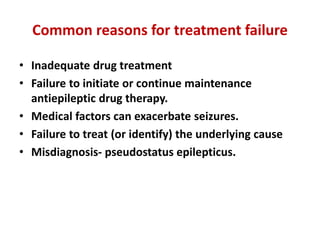

This document discusses the management of pediatric status epilepticus. It defines status epilepticus as continuous seizure activity lasting more than 30 minutes or two or more sequential seizures without recovery of consciousness. Management involves early treatment with benzodiazepines like midazolam or lorazepam. If seizures continue, second-line treatments including fosphenytoin, phenytoin, valproate, or phenobarbital are used. Refractory status epilepticus is defined as continuous seizures lasting over 60 minutes despite initial treatment. It requires intensive care management including anesthetic agents like propofol to induce burst suppression on EEG.