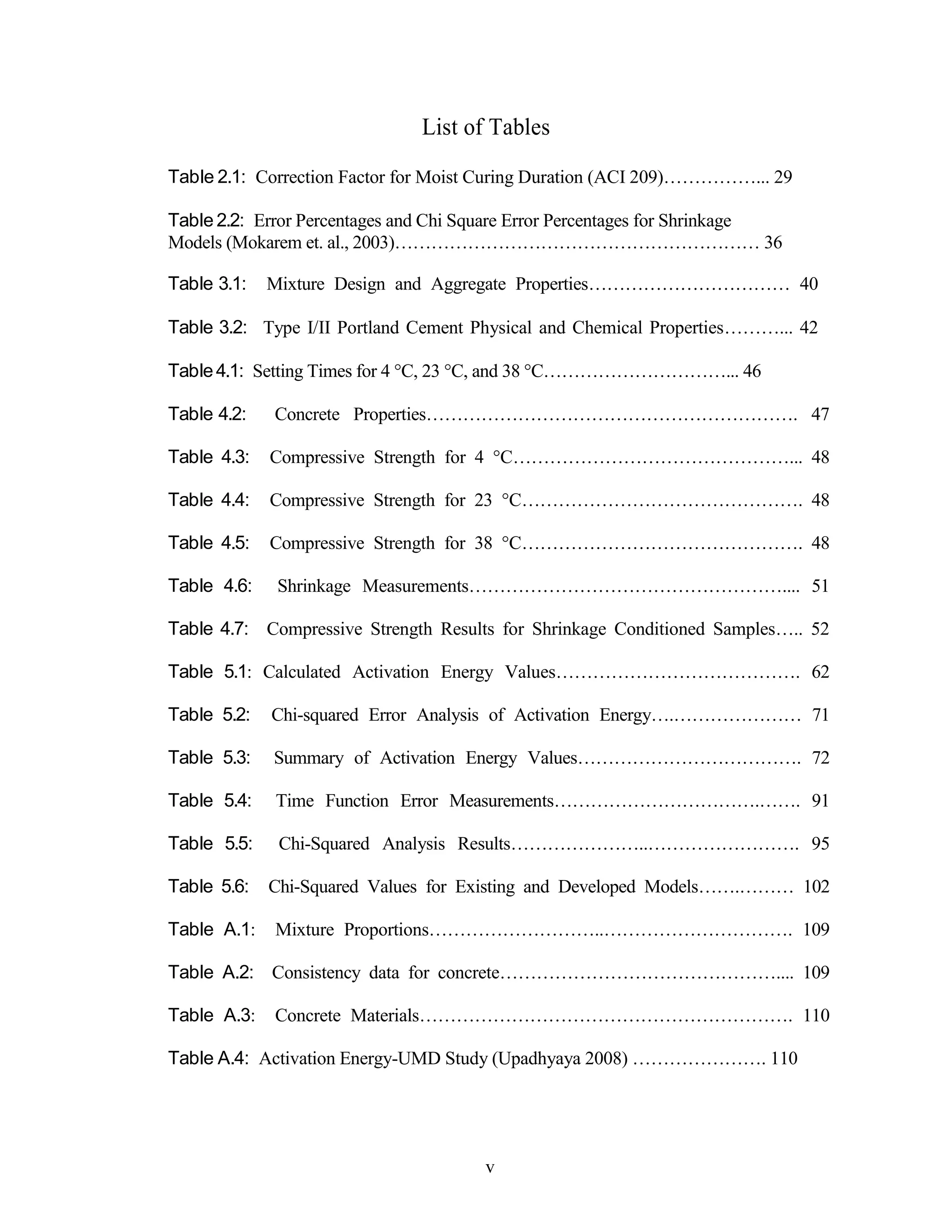

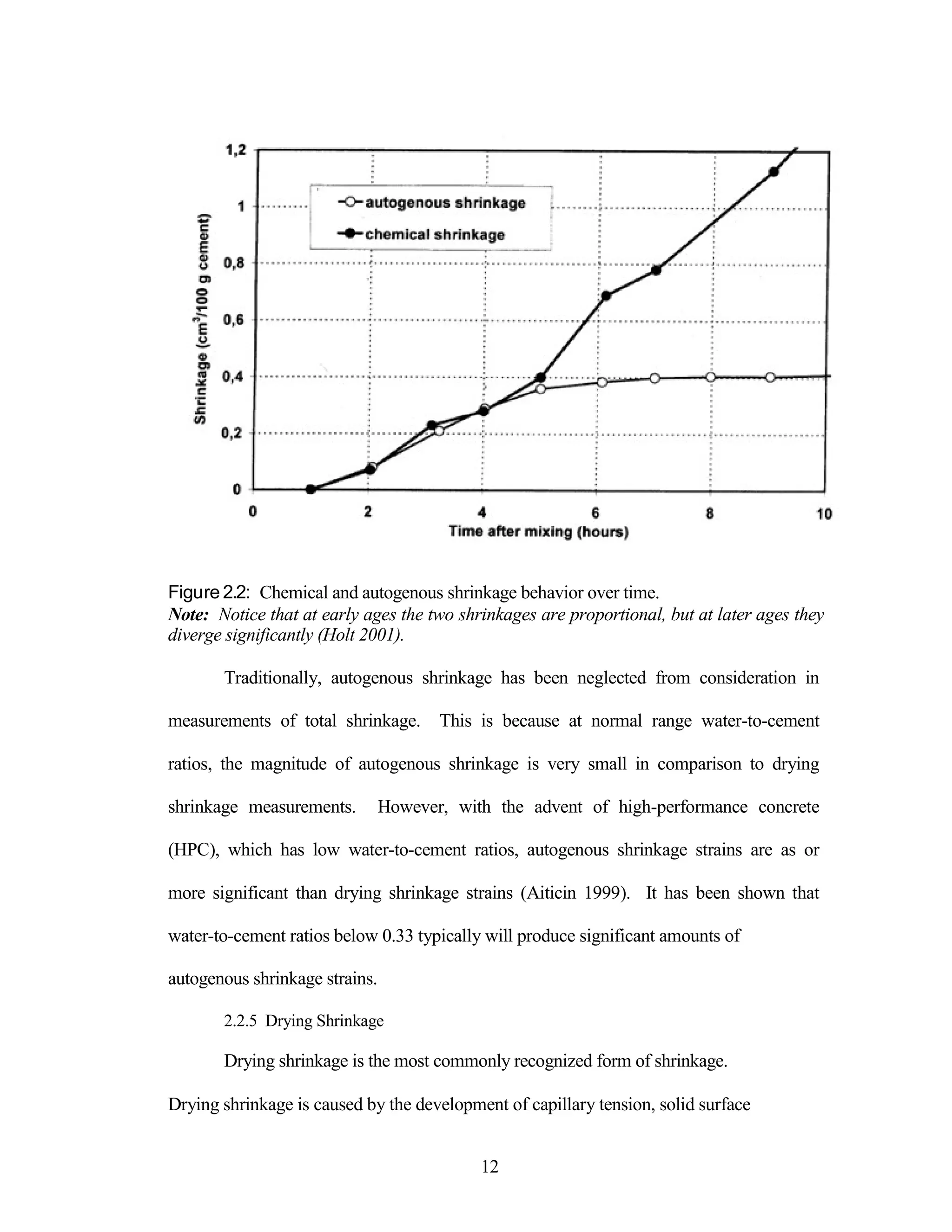

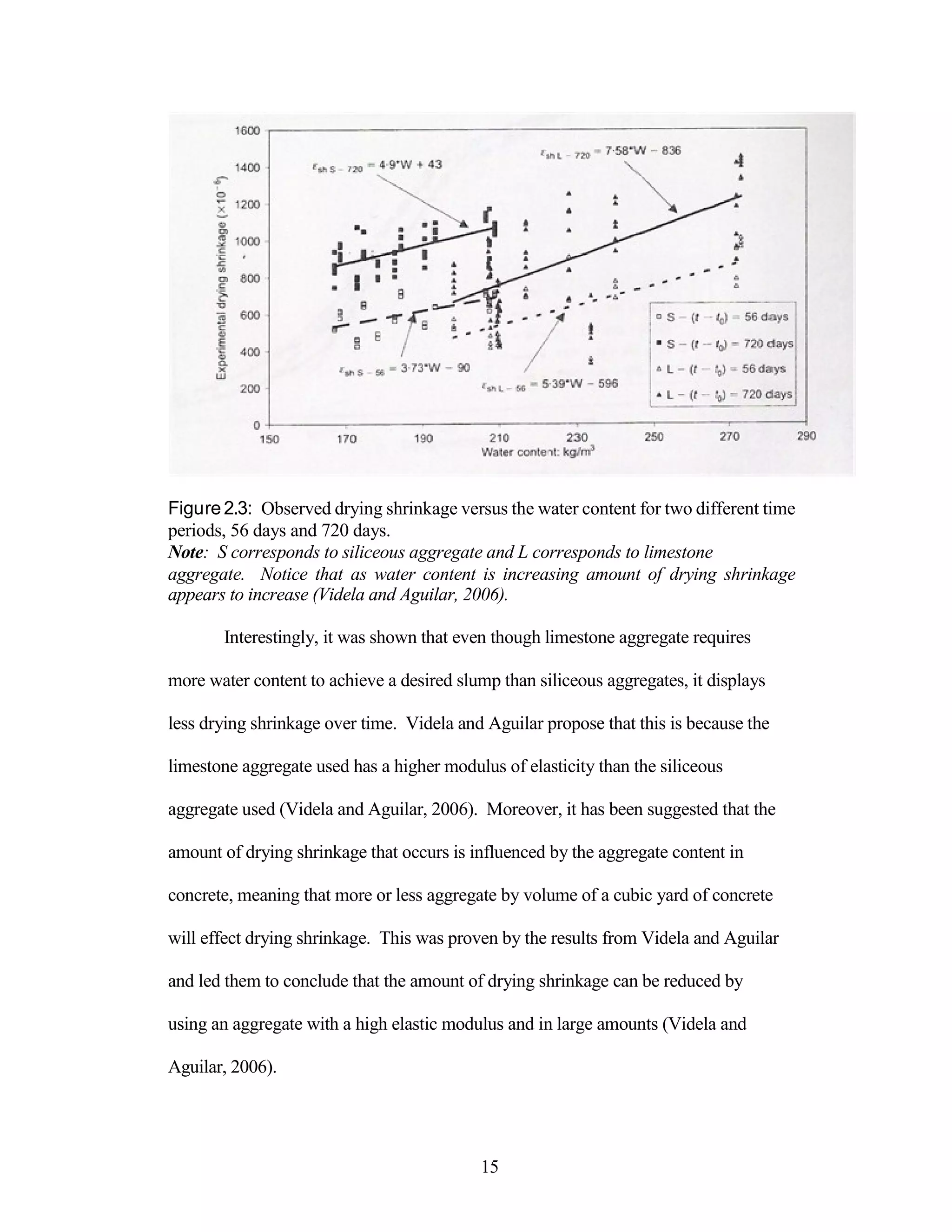

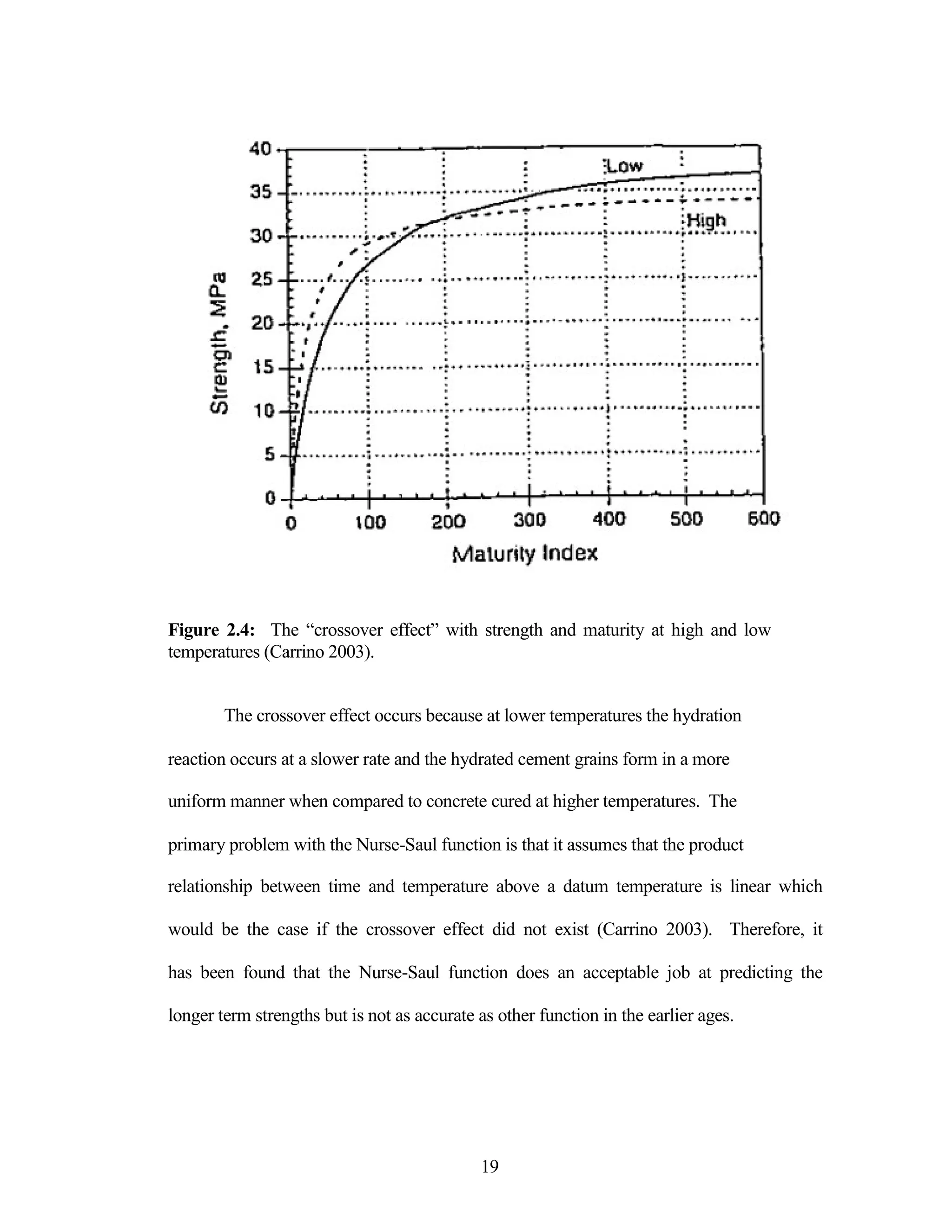

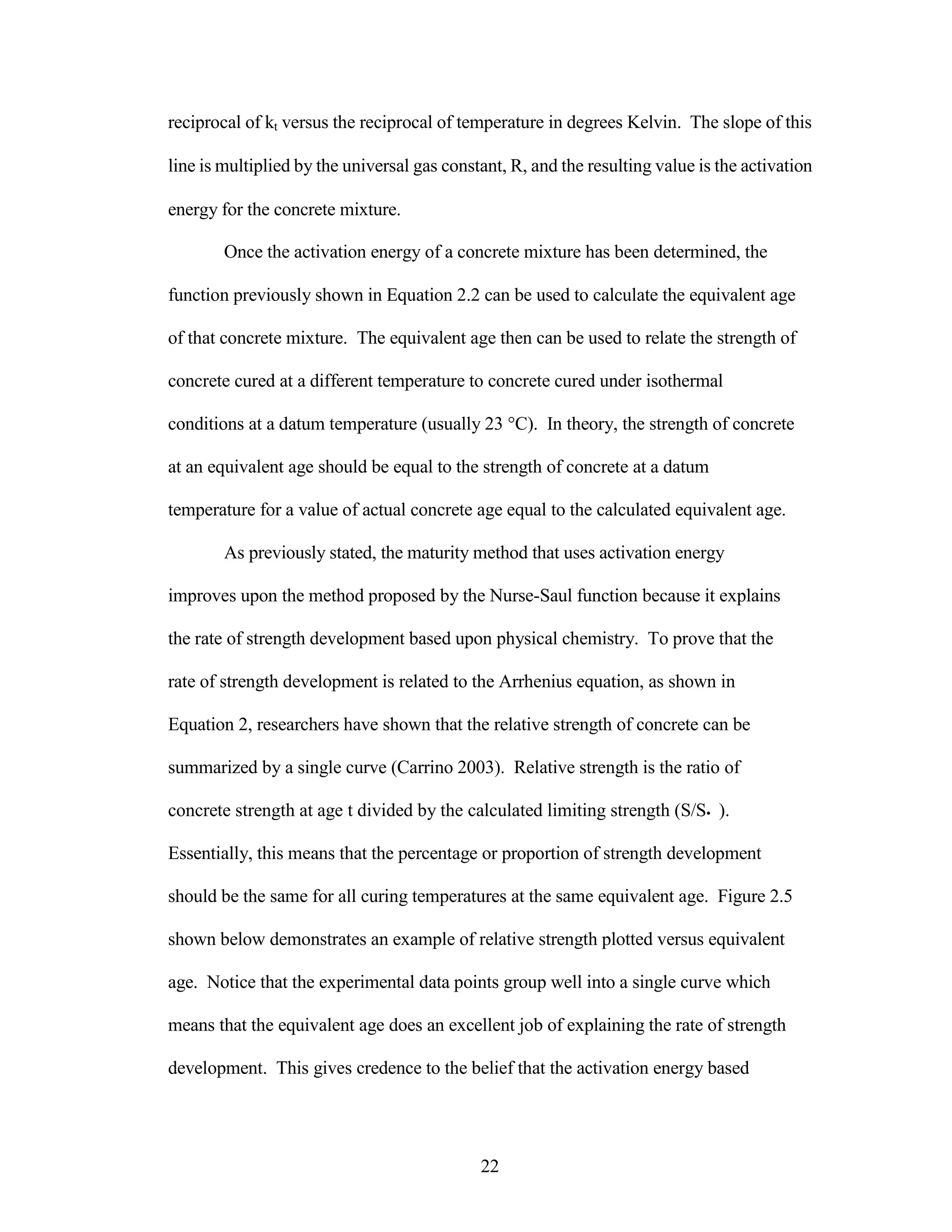

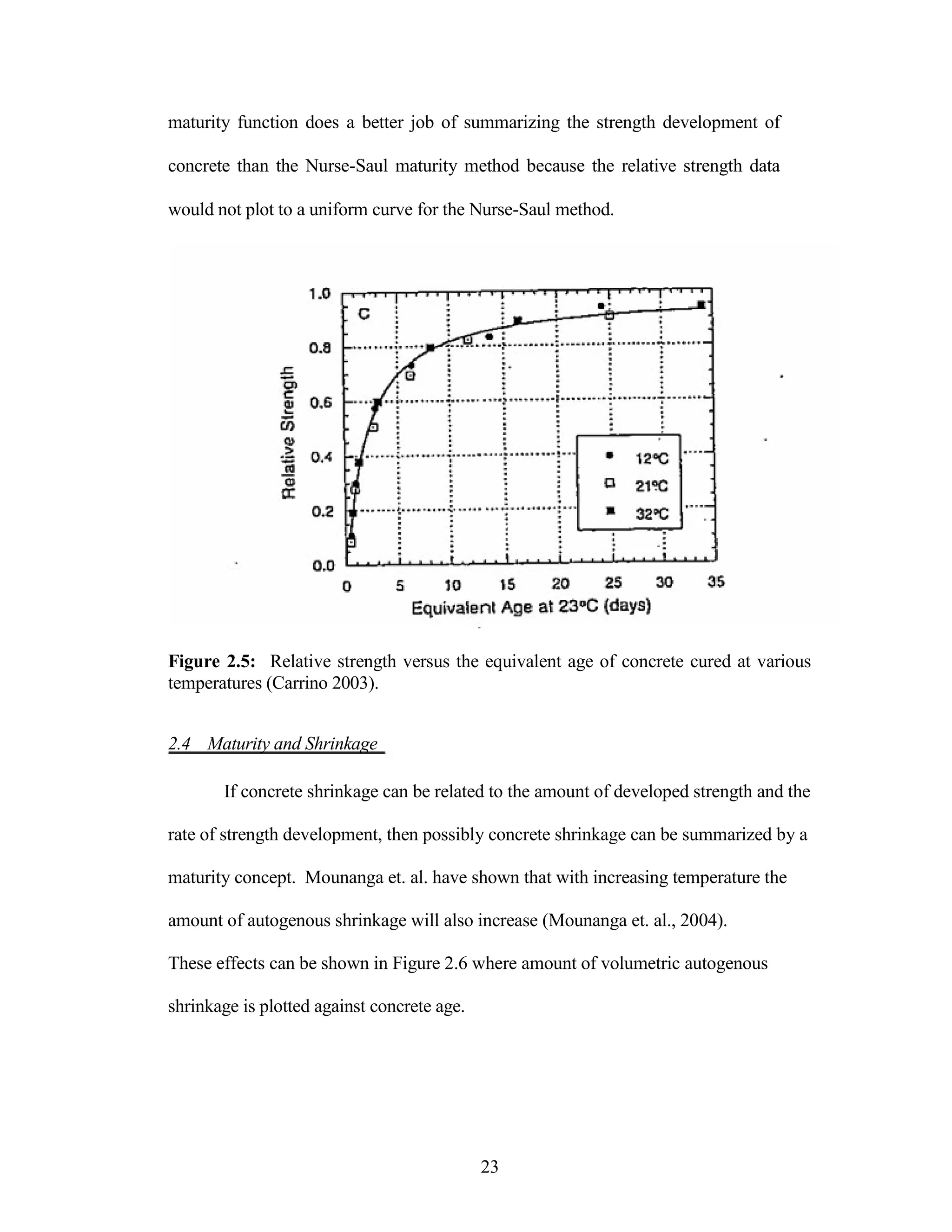

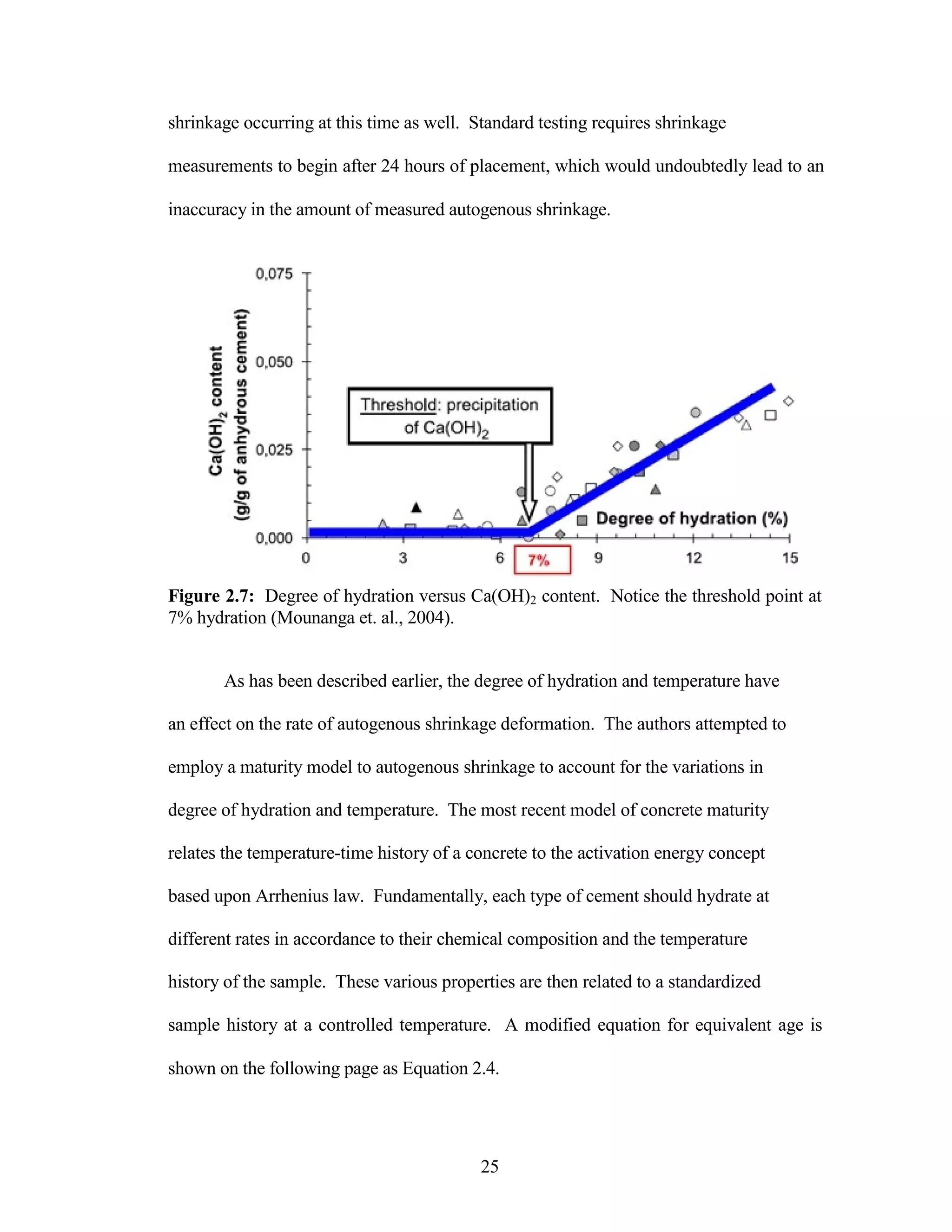

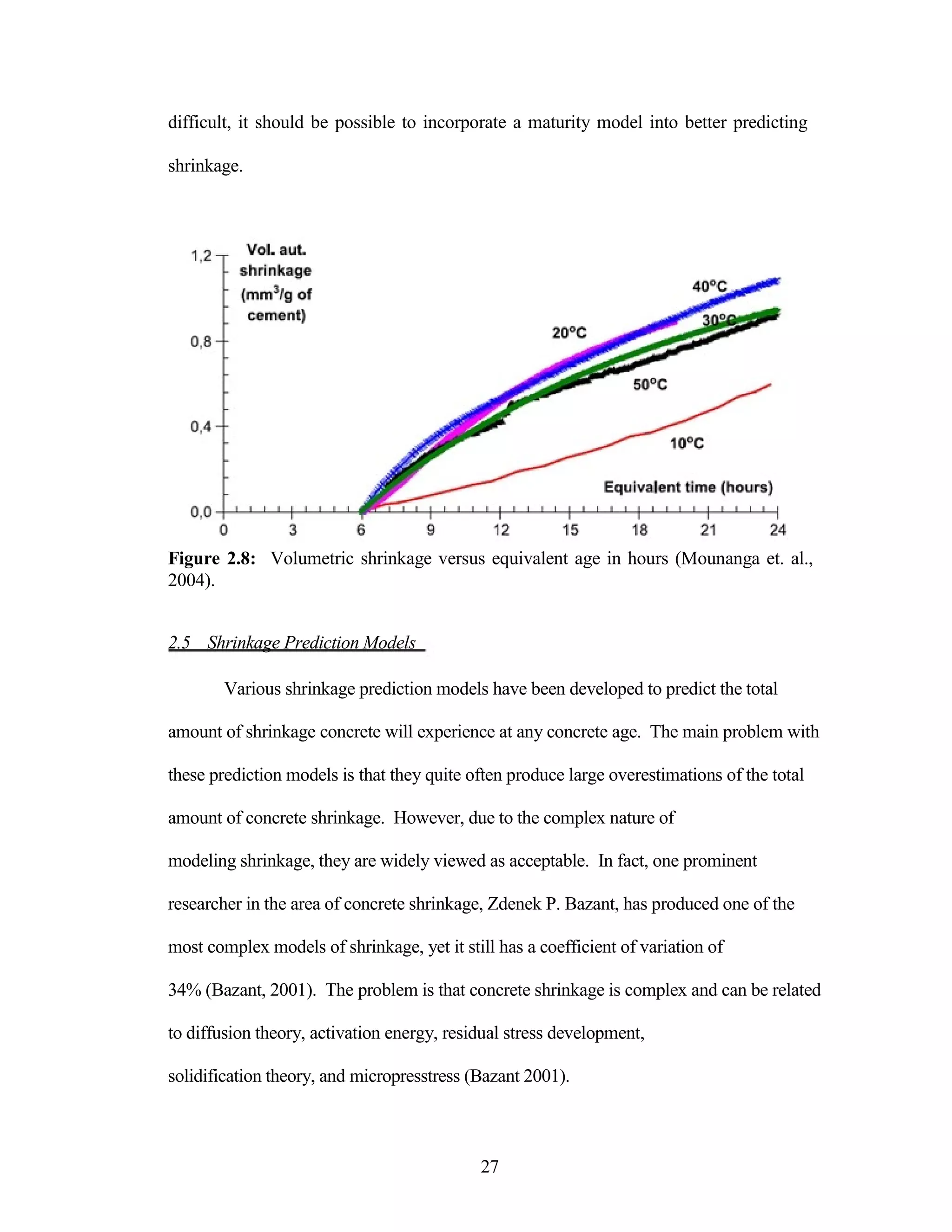

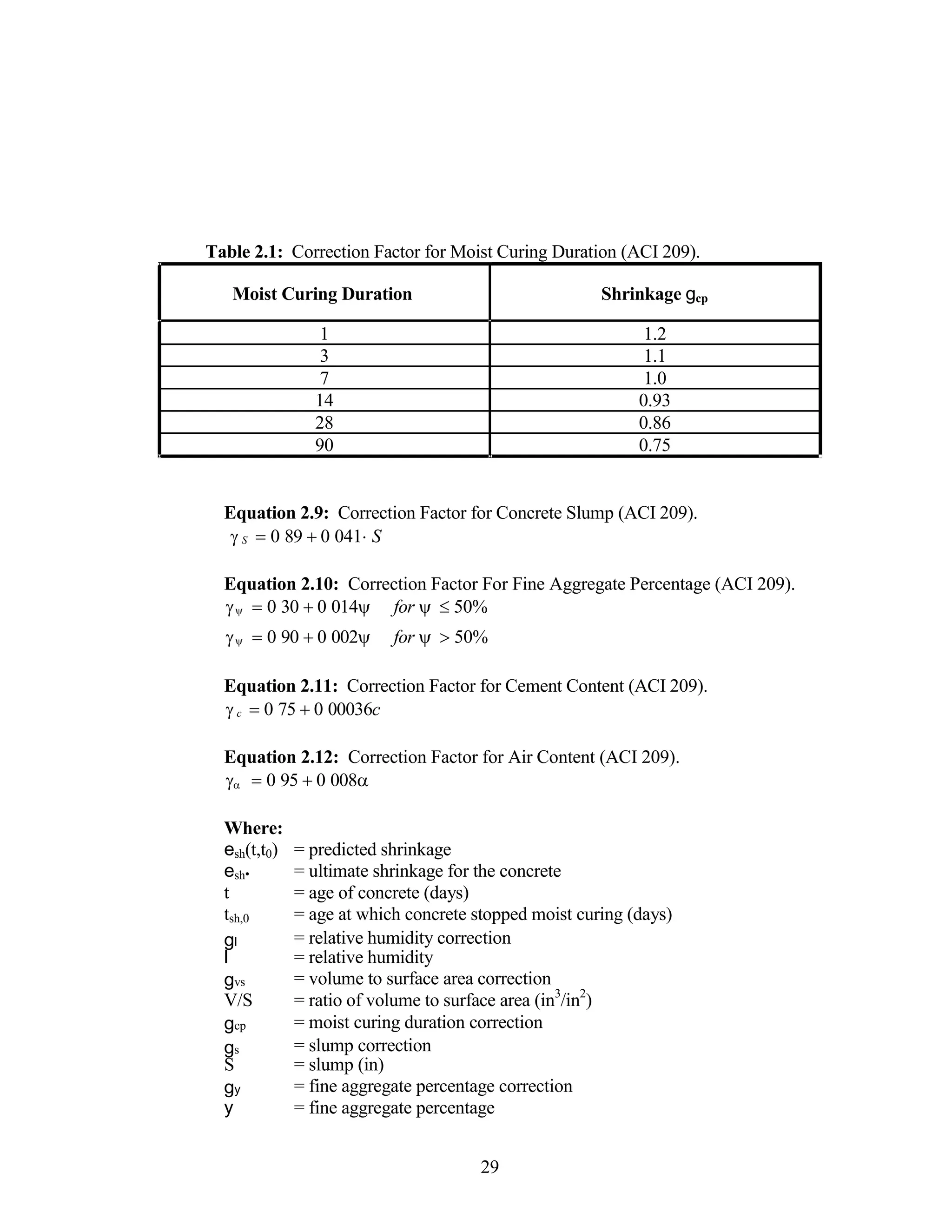

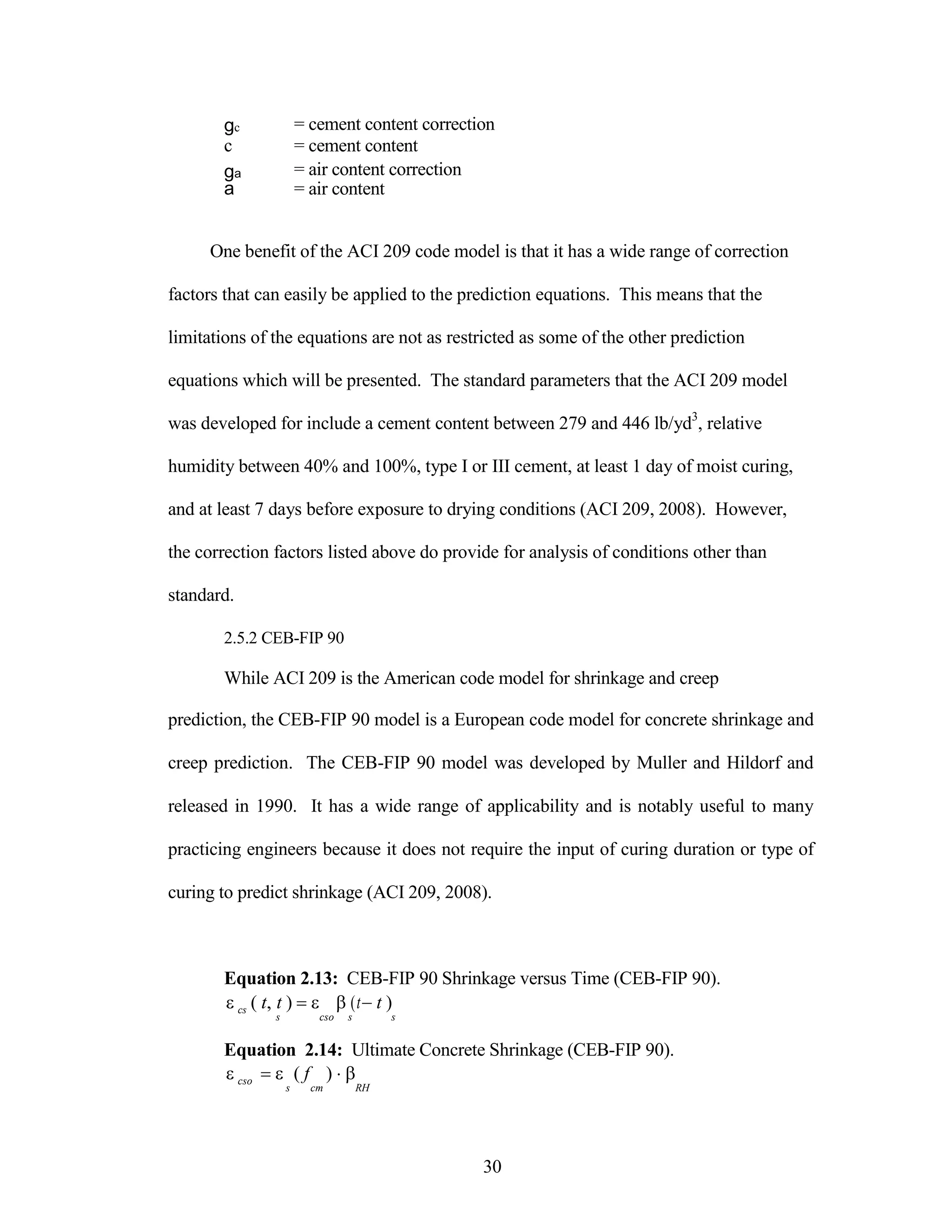

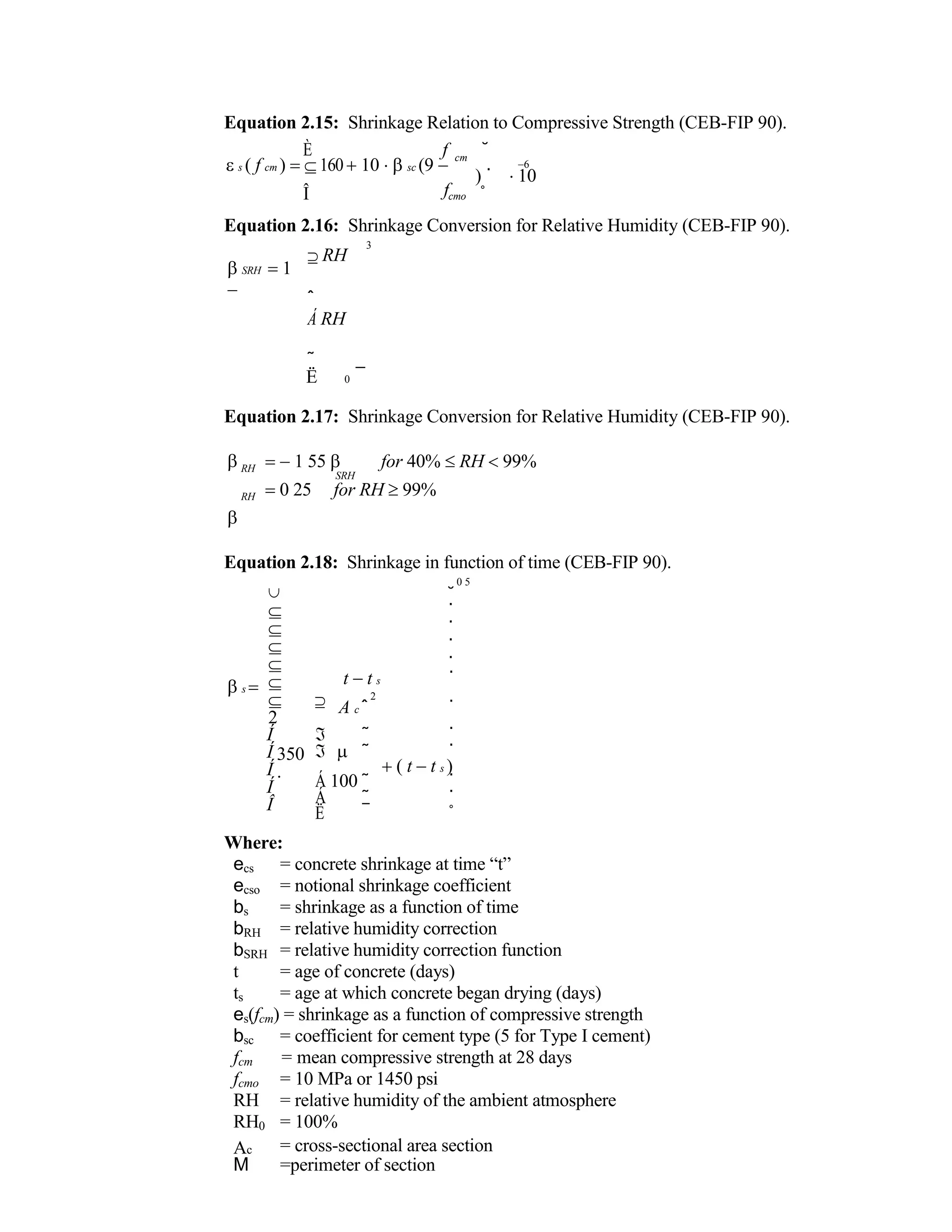

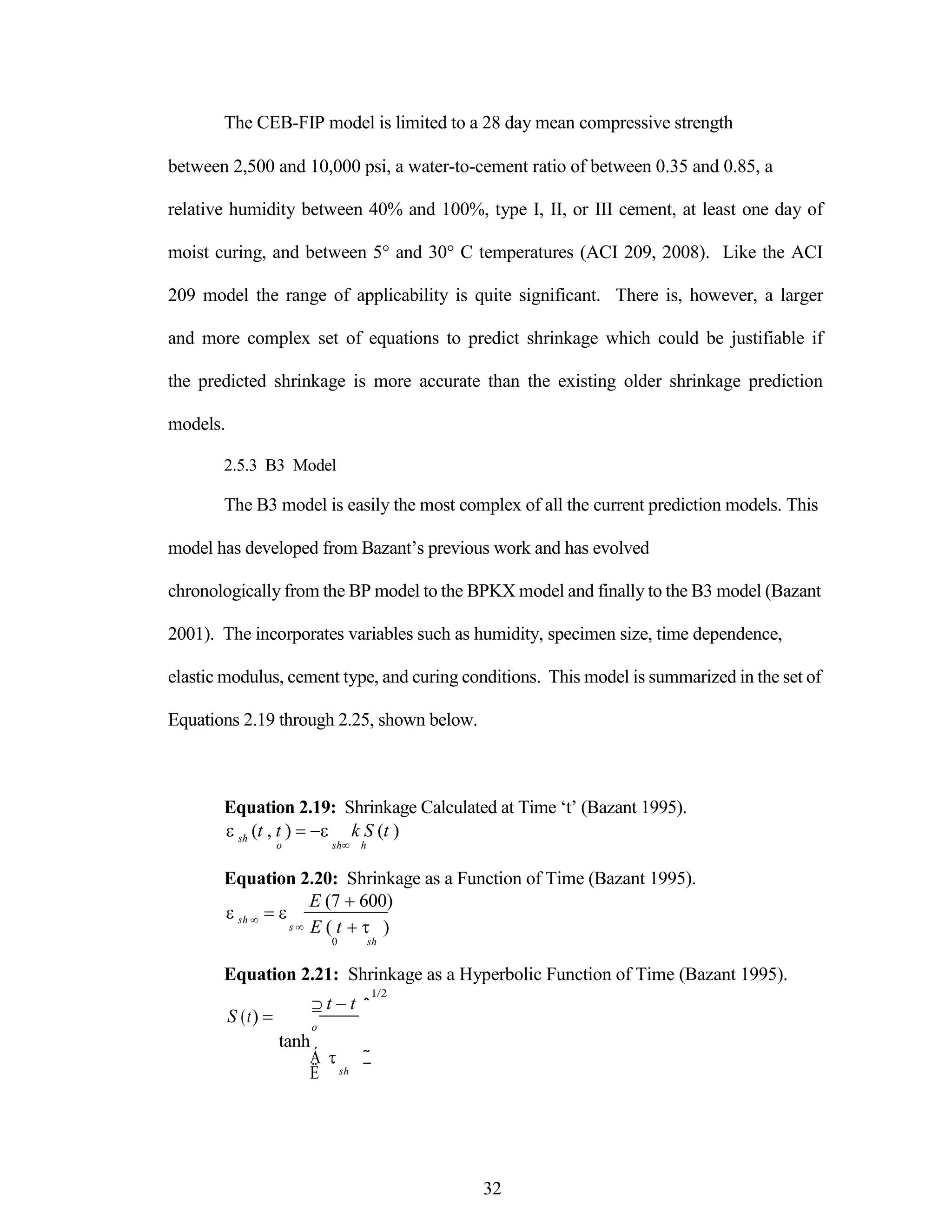

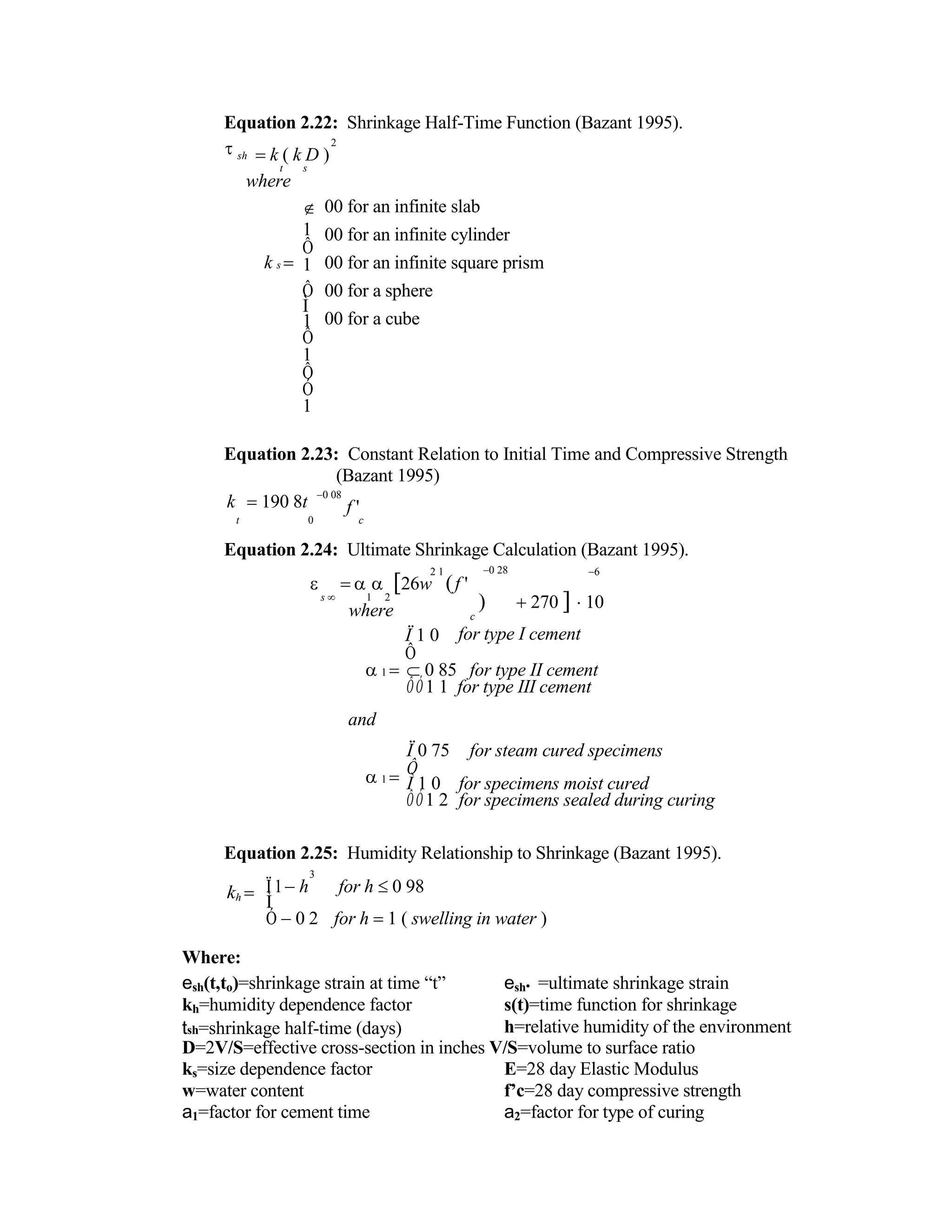

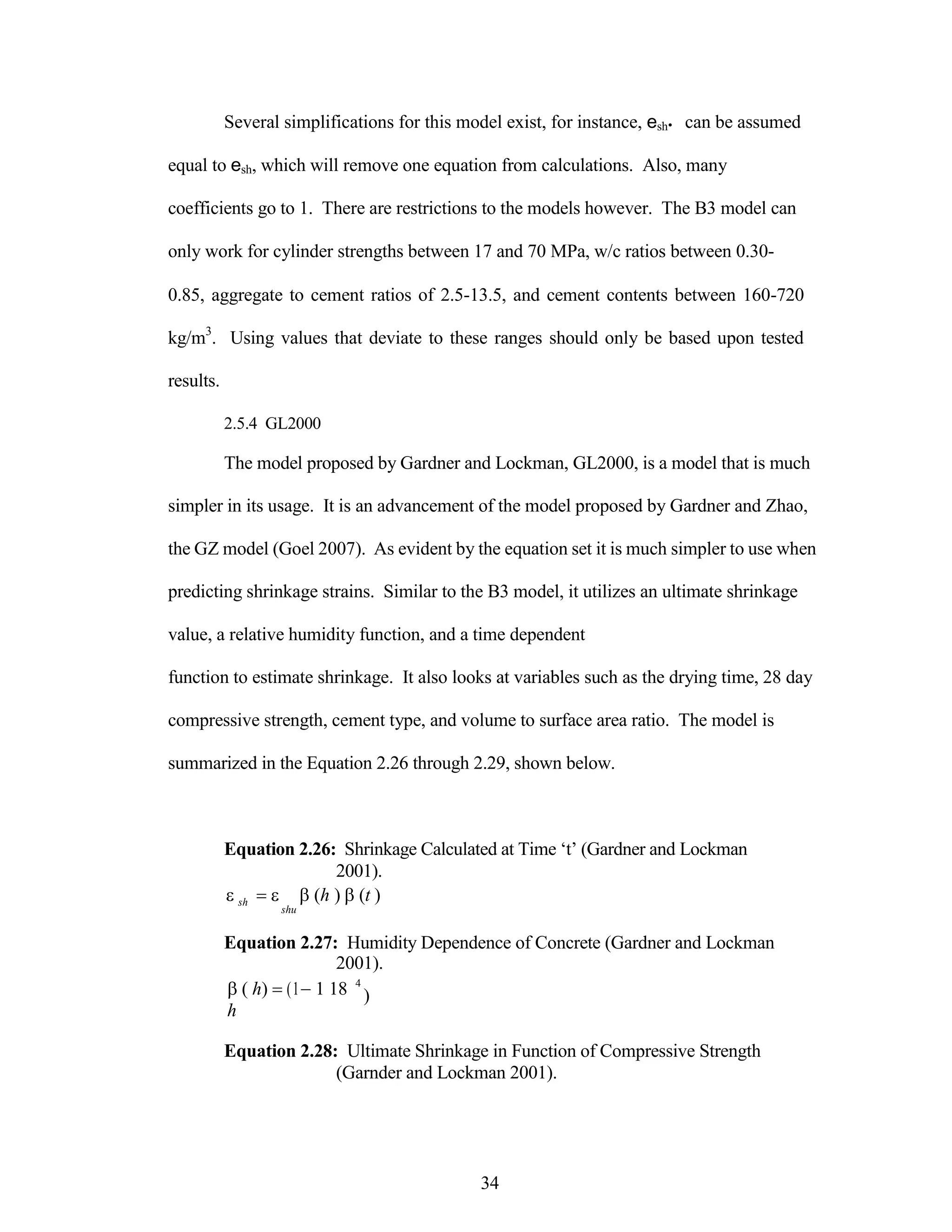

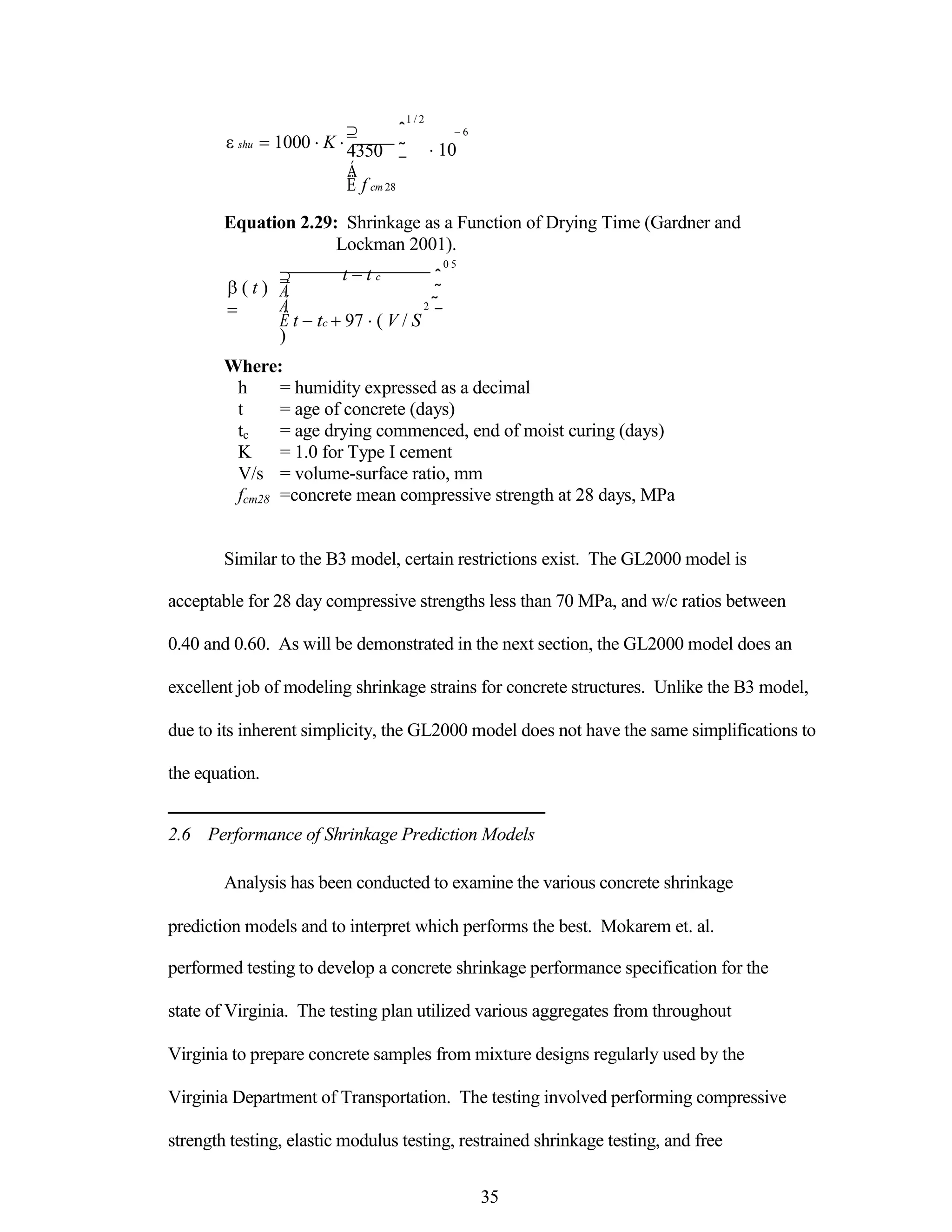

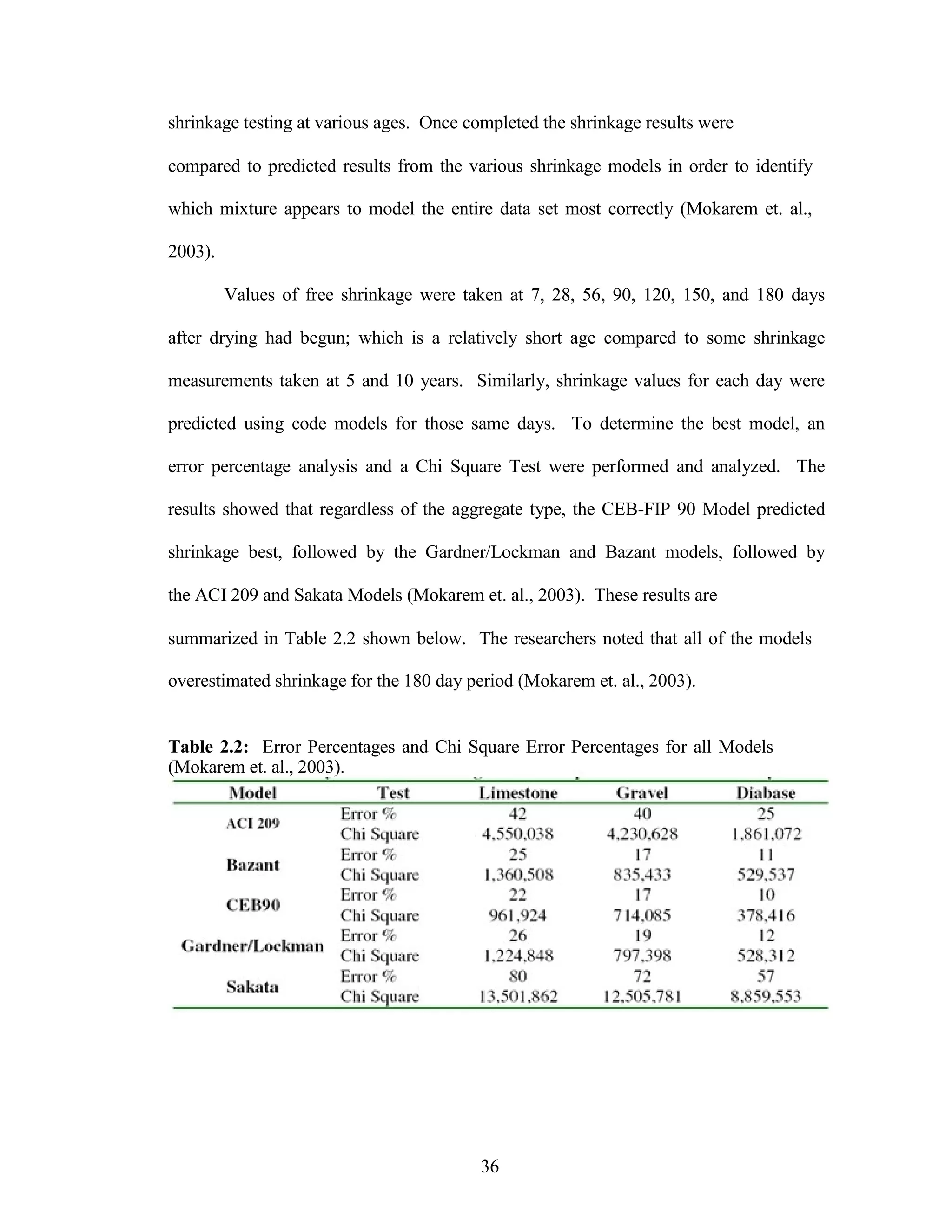

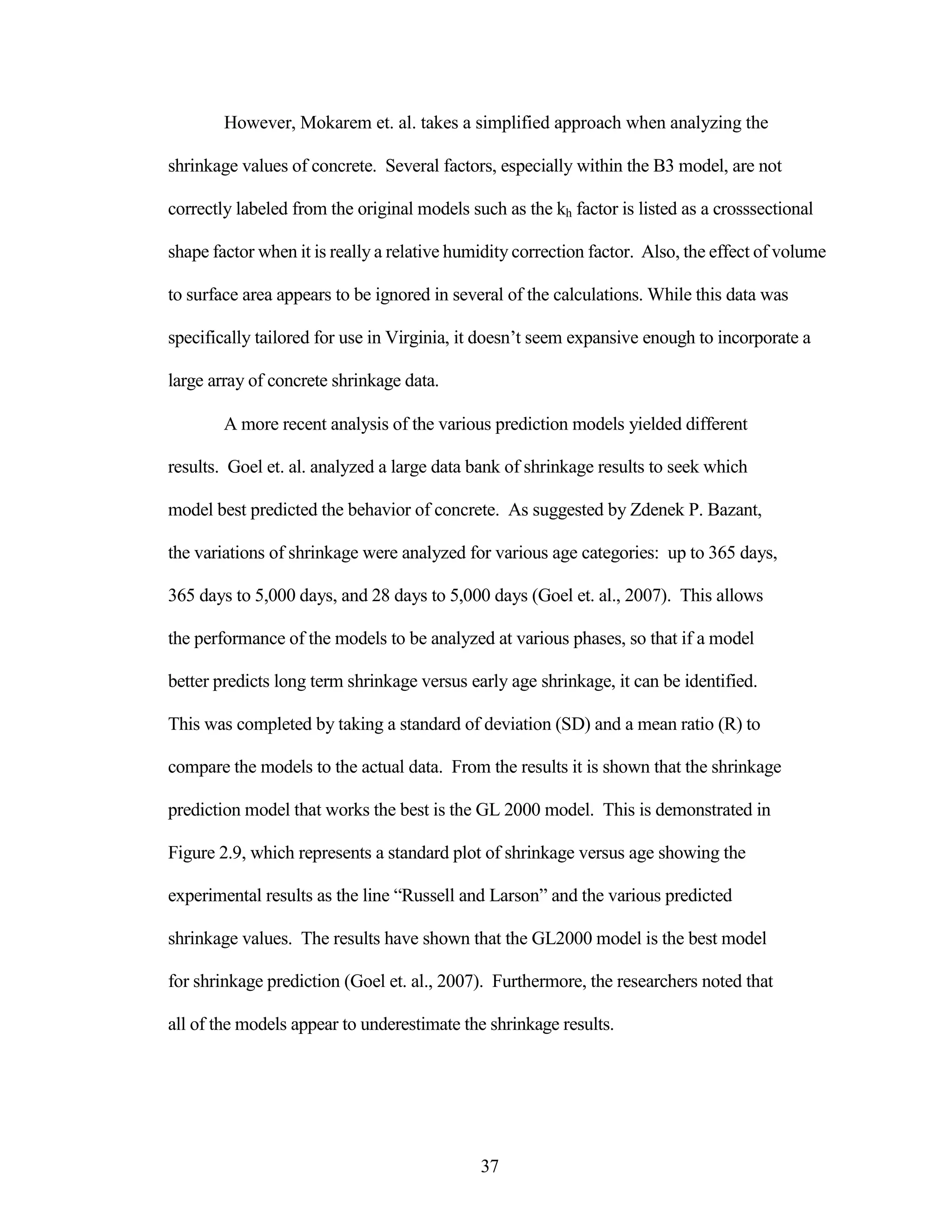

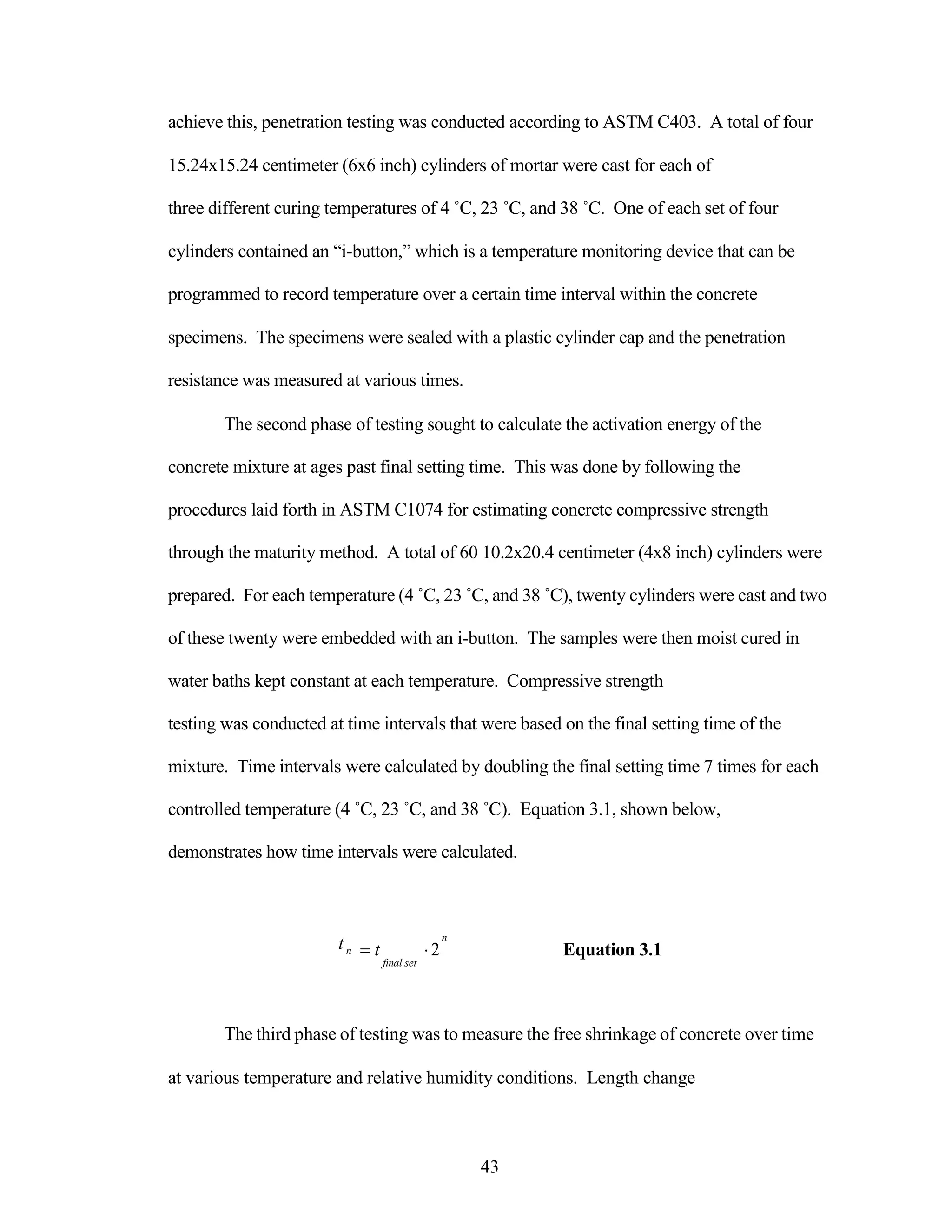

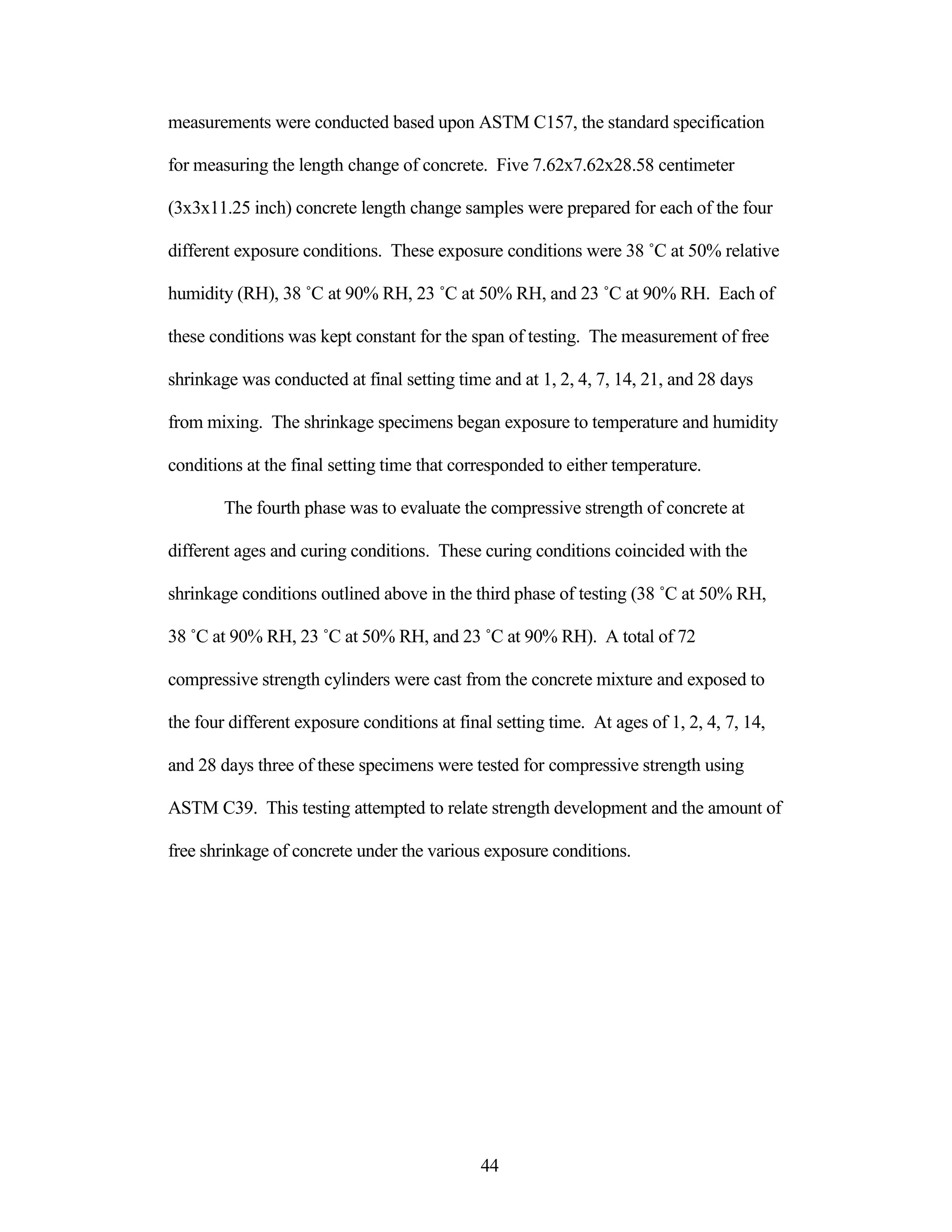

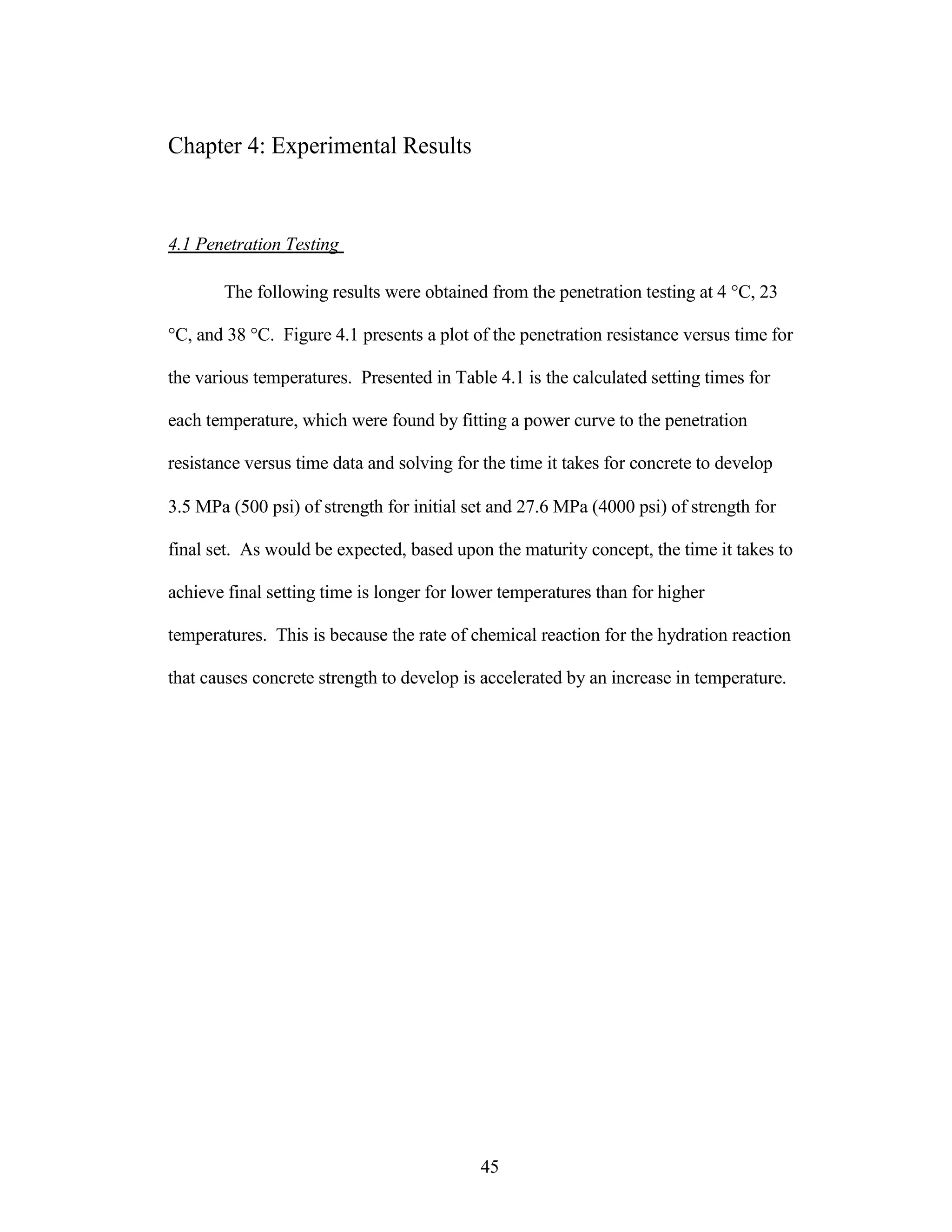

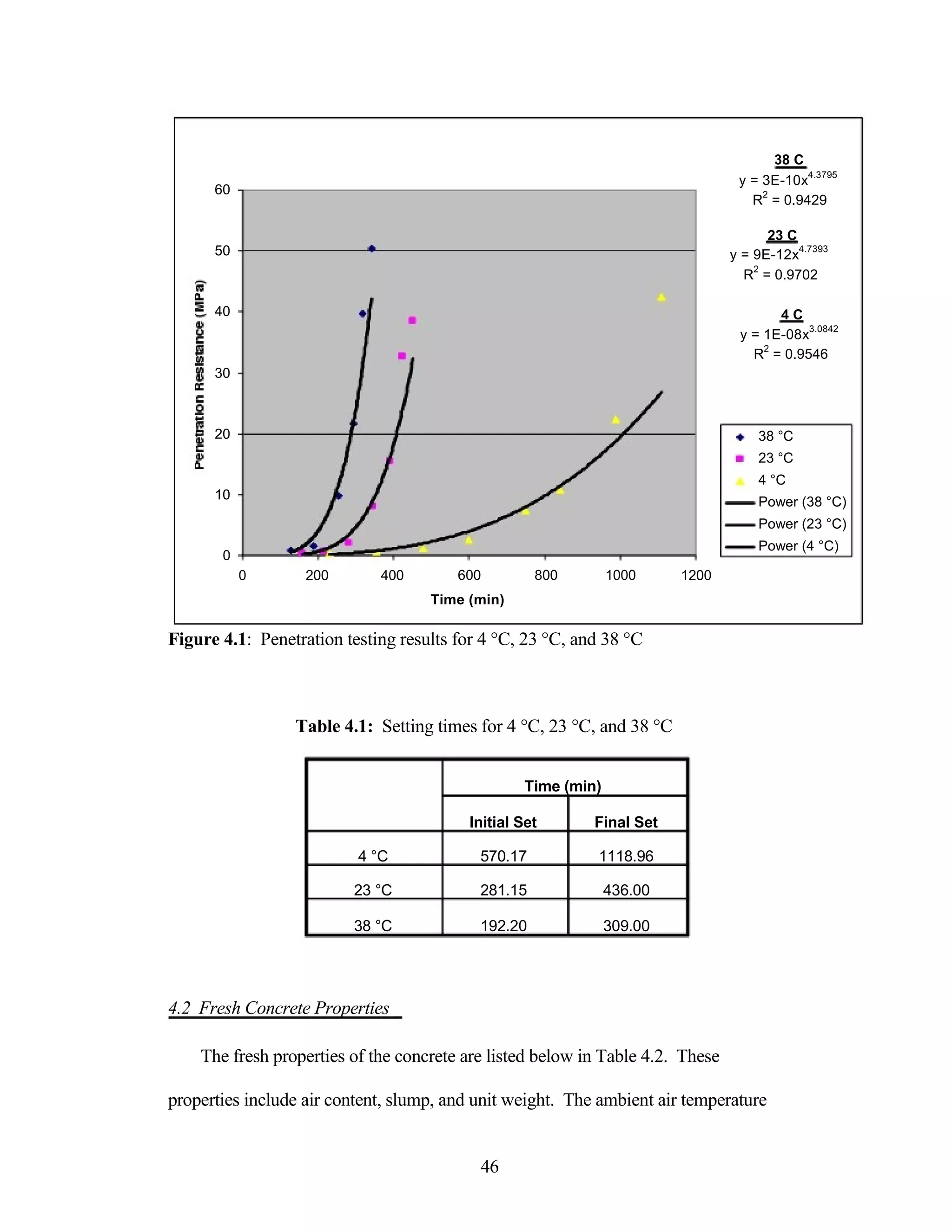

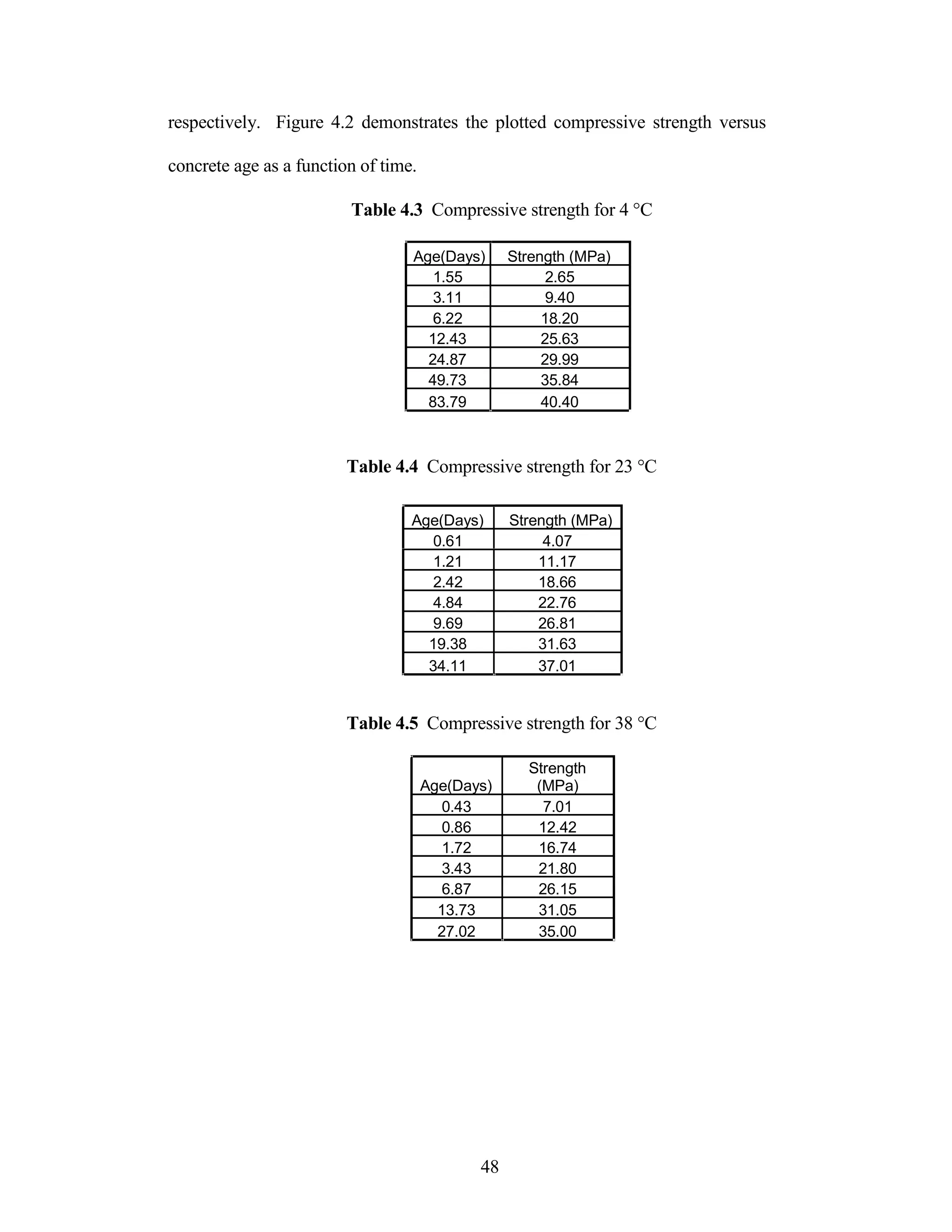

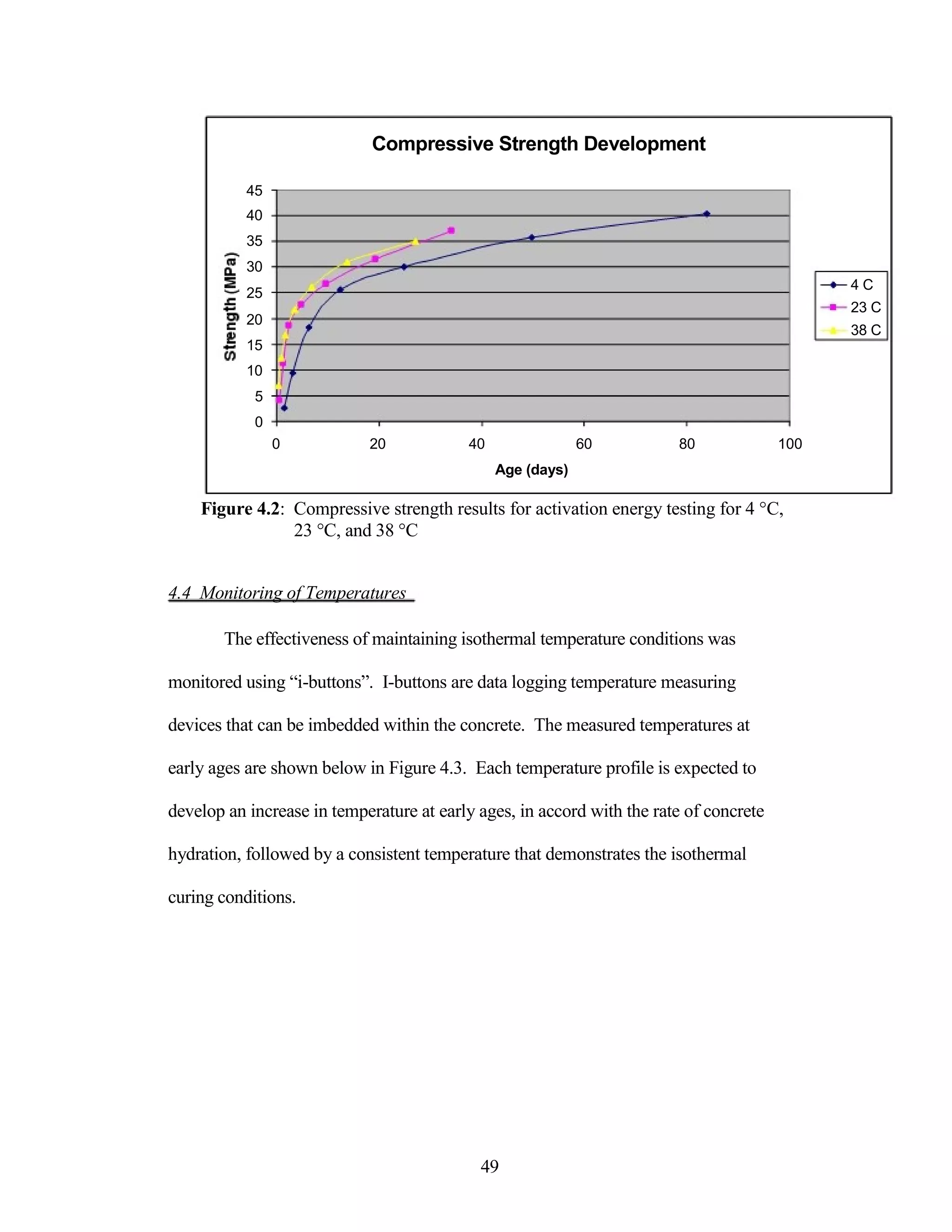

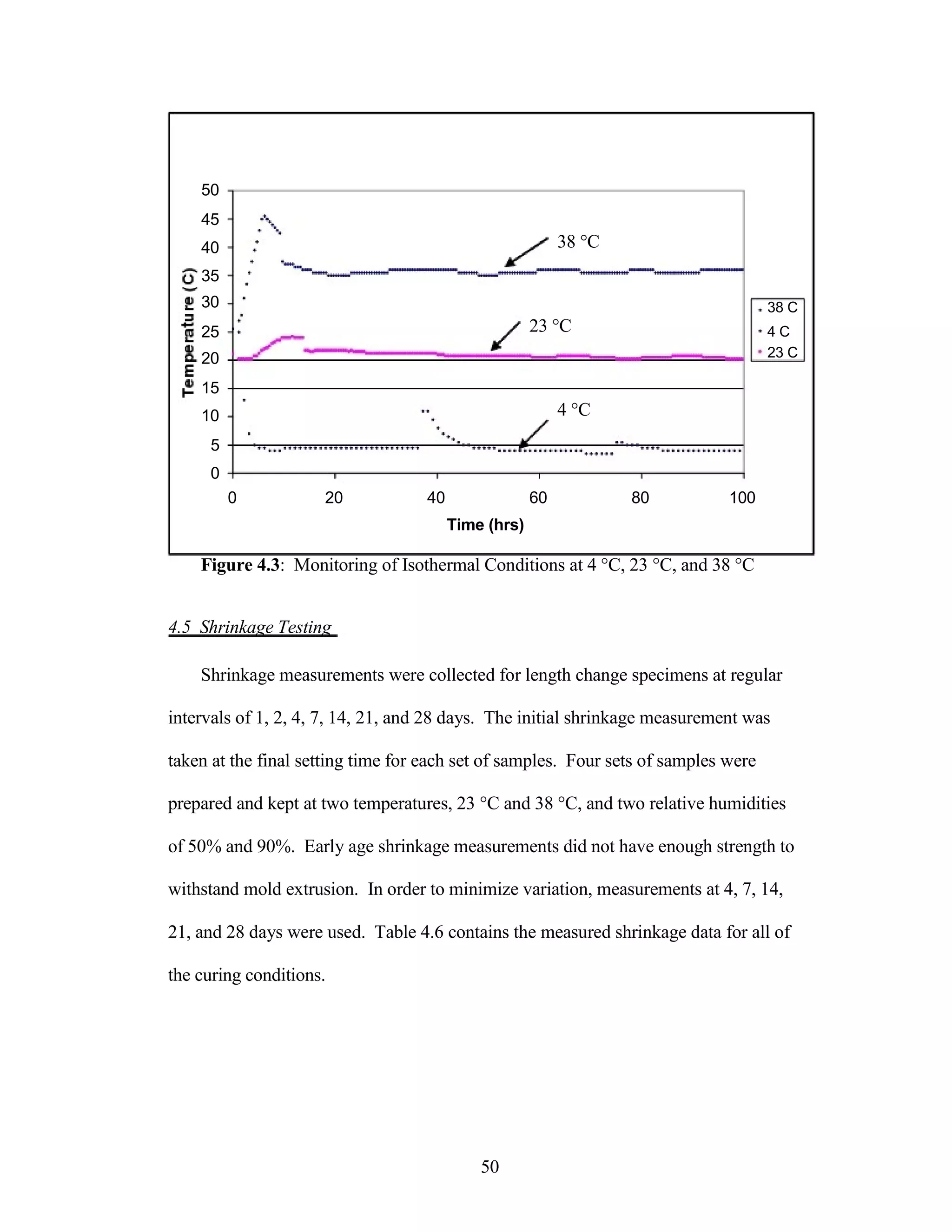

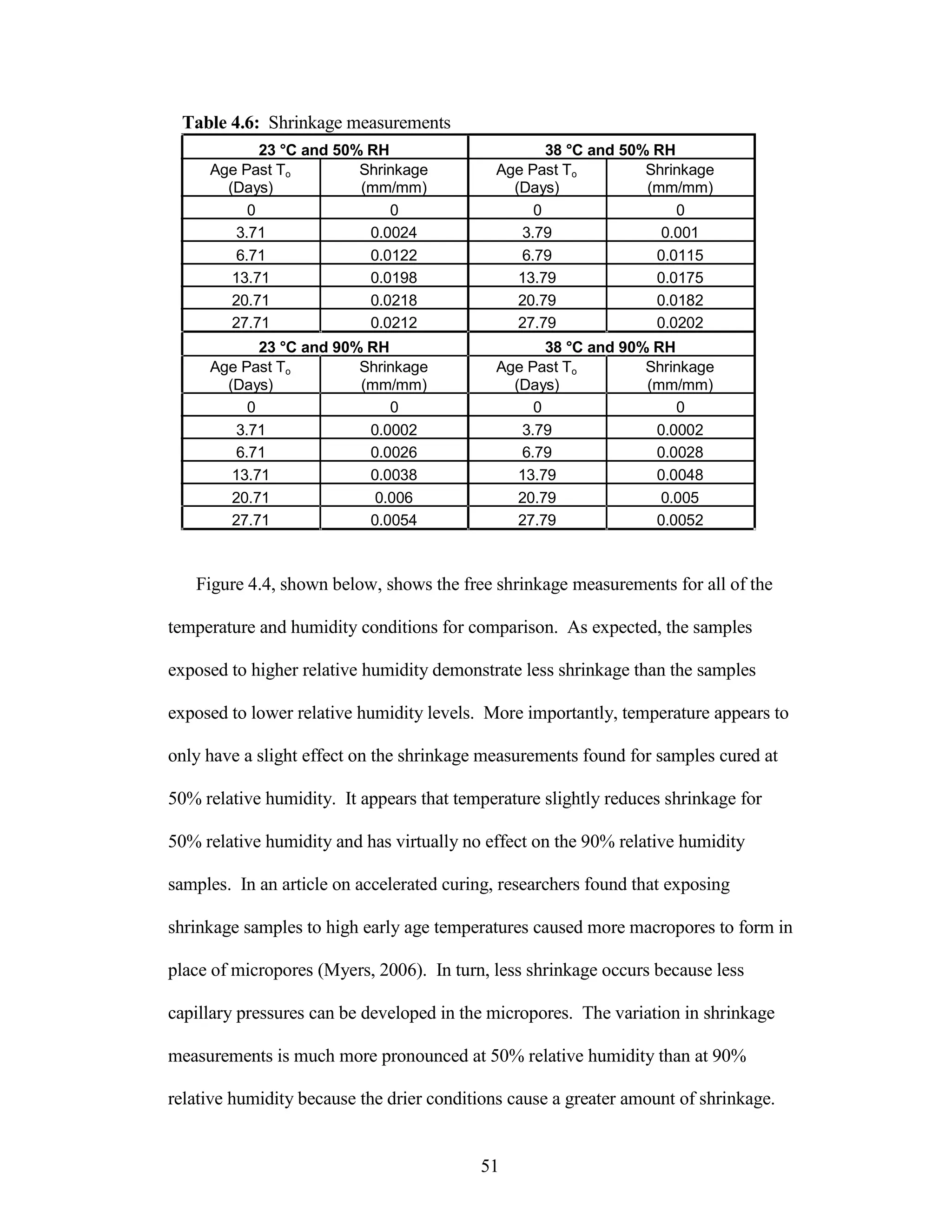

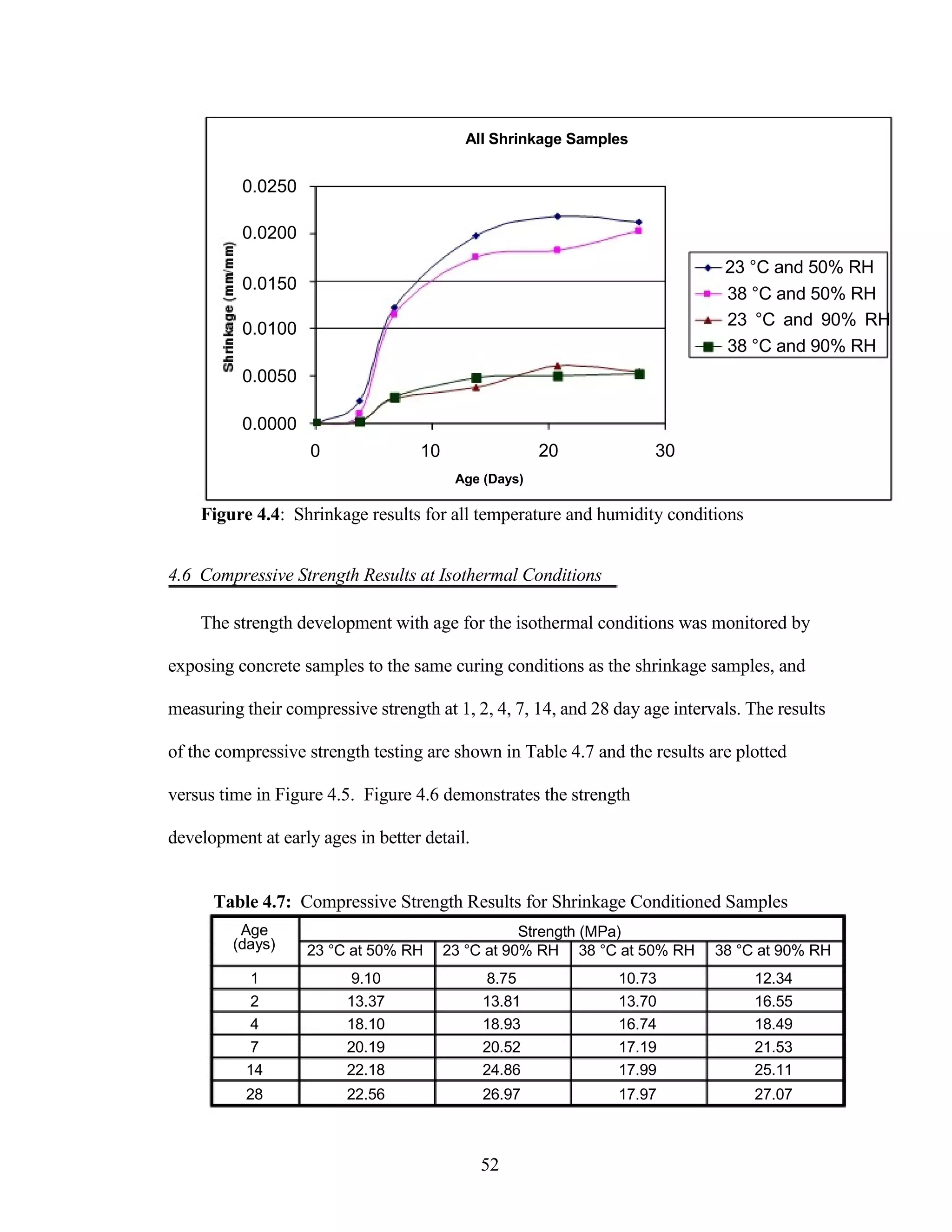

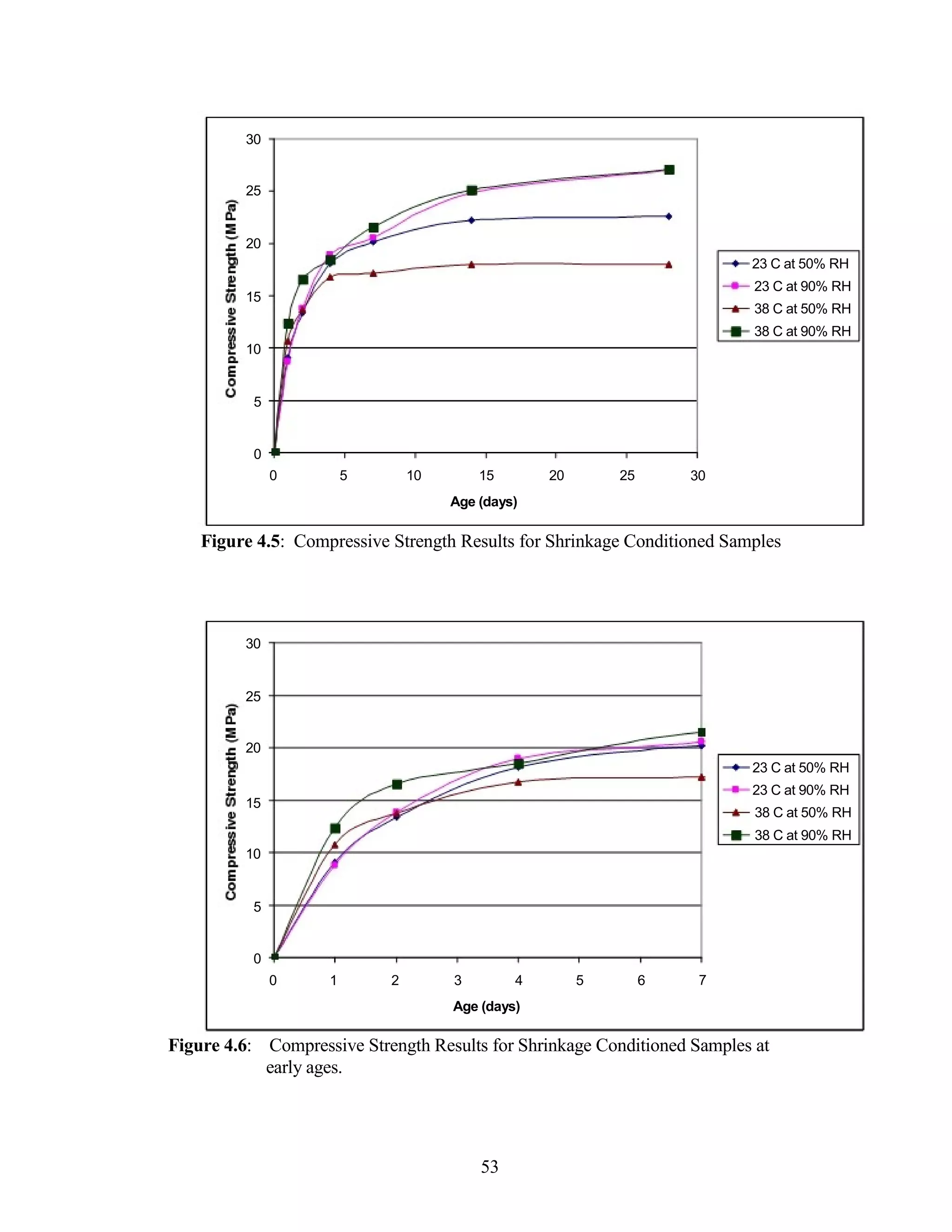

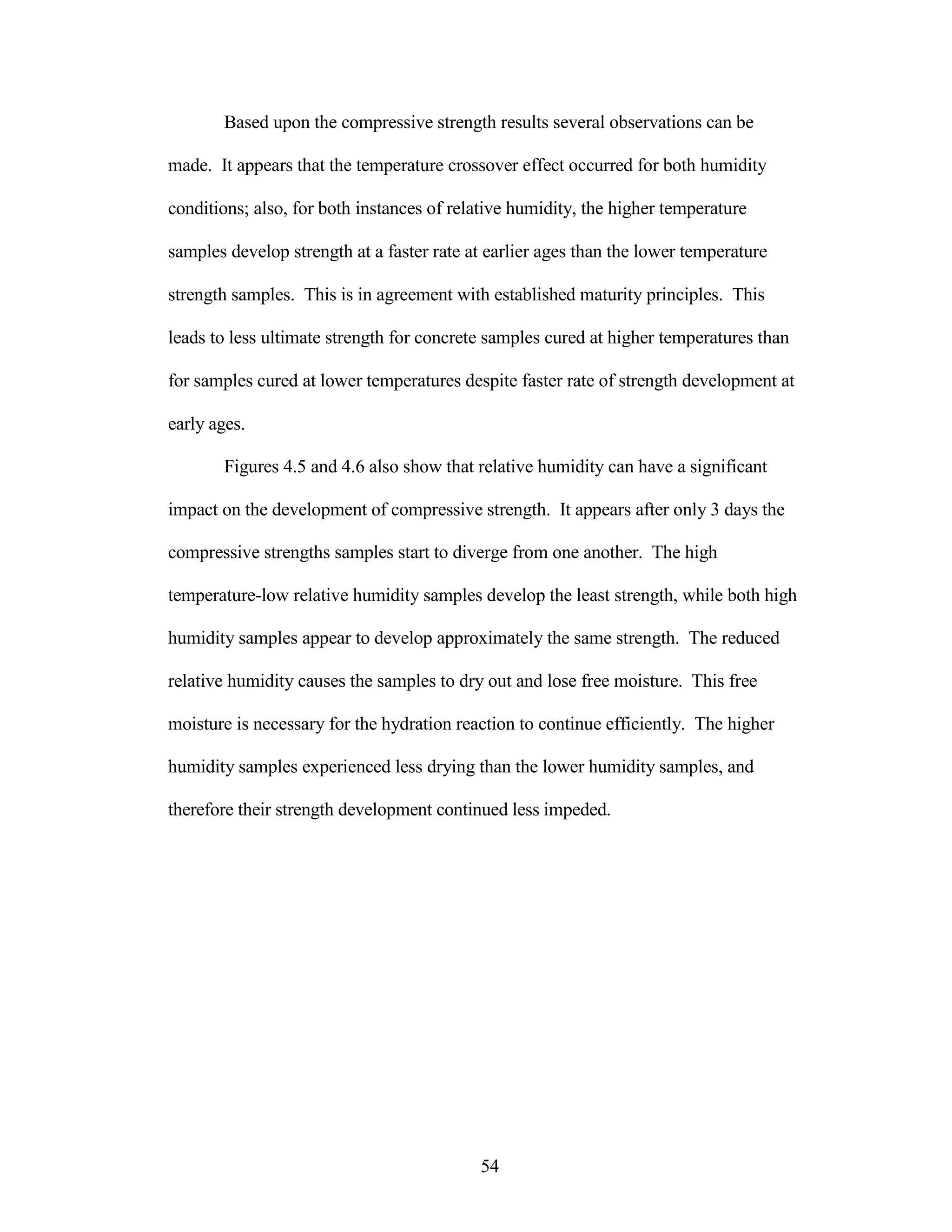

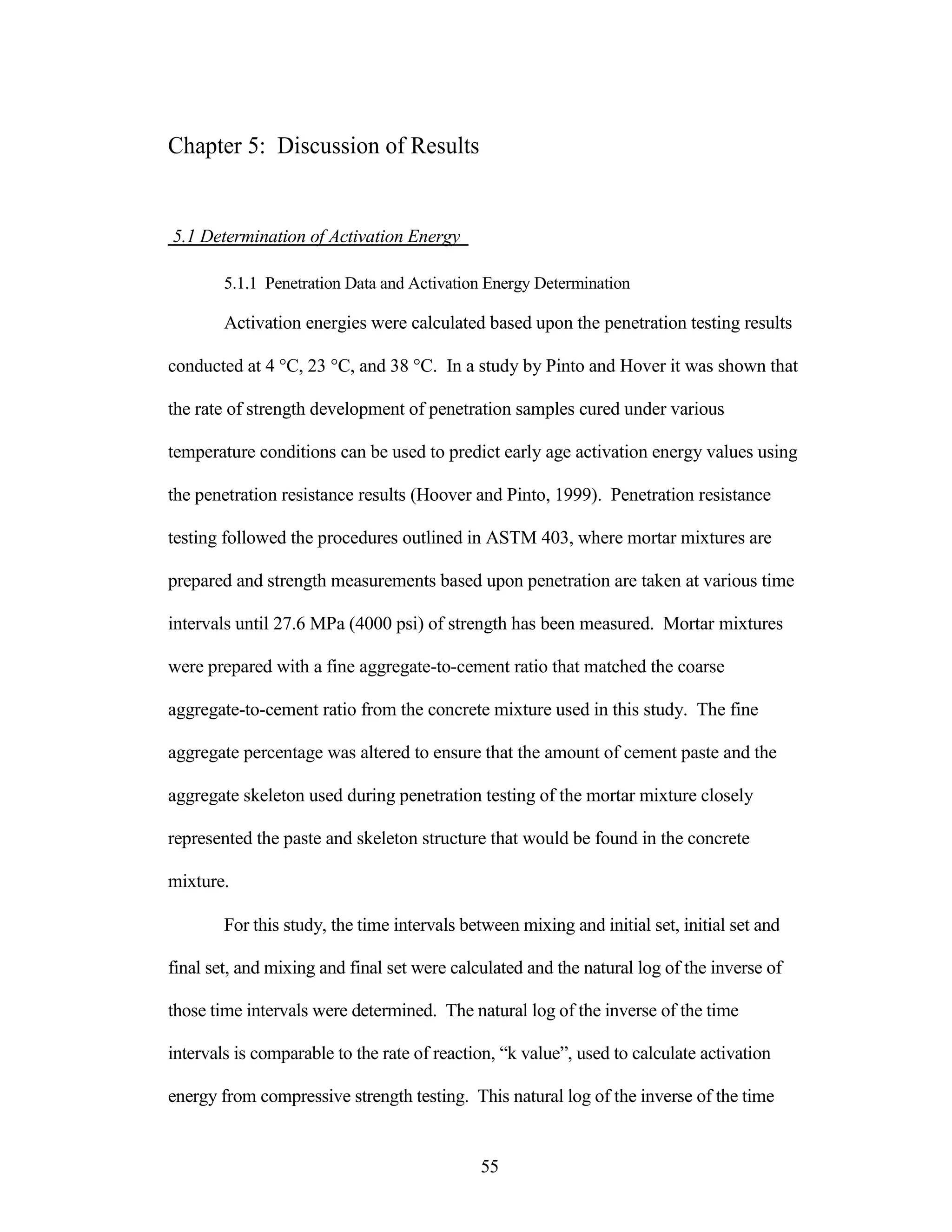

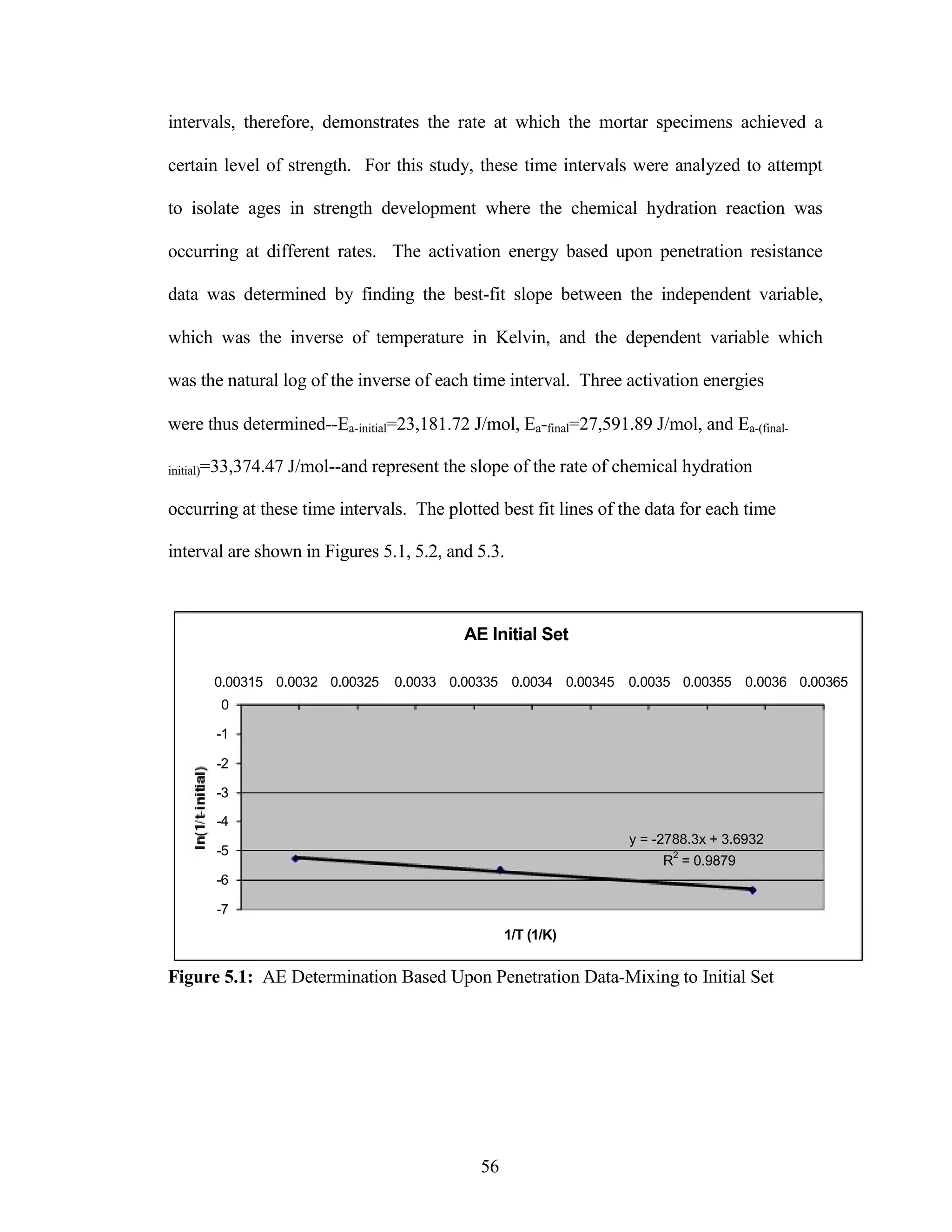

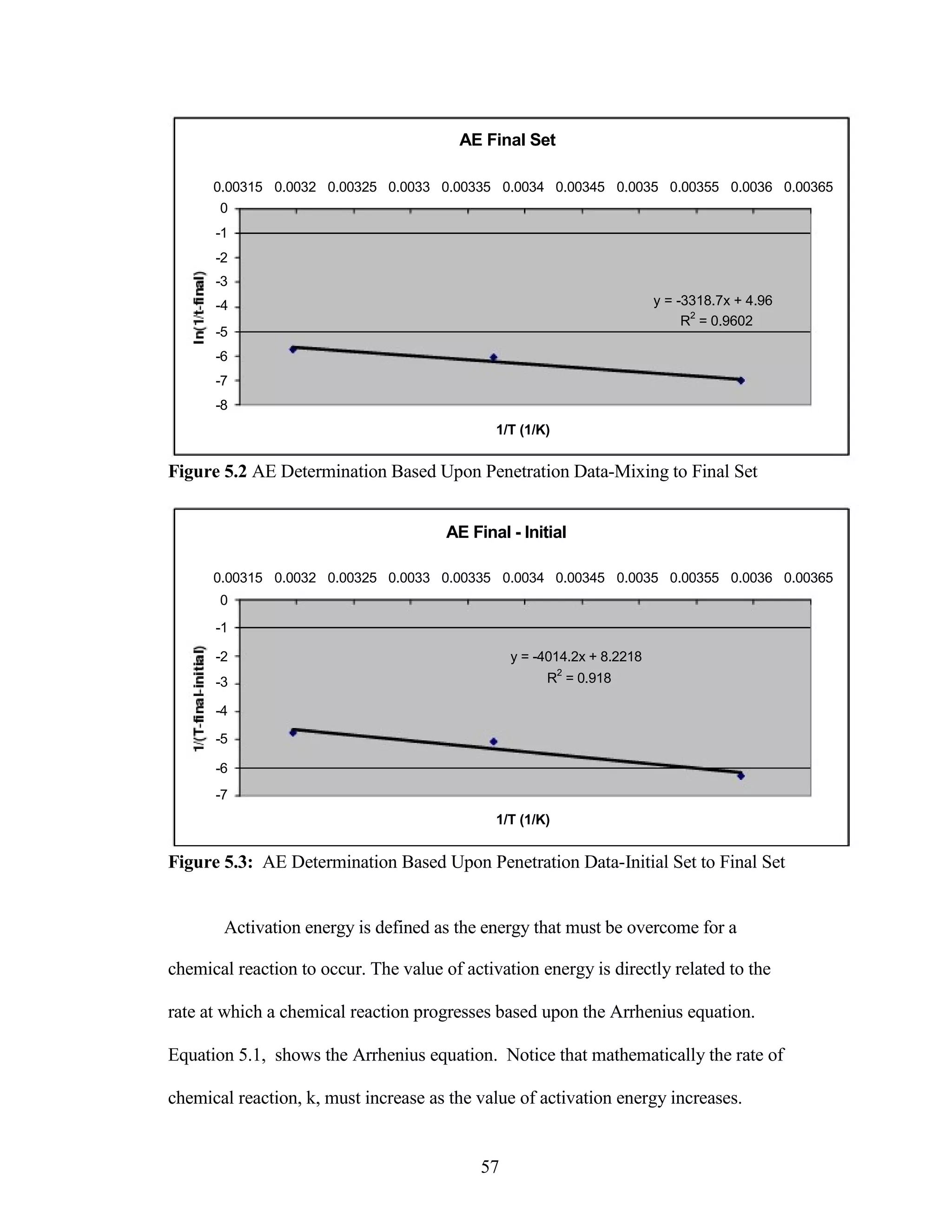

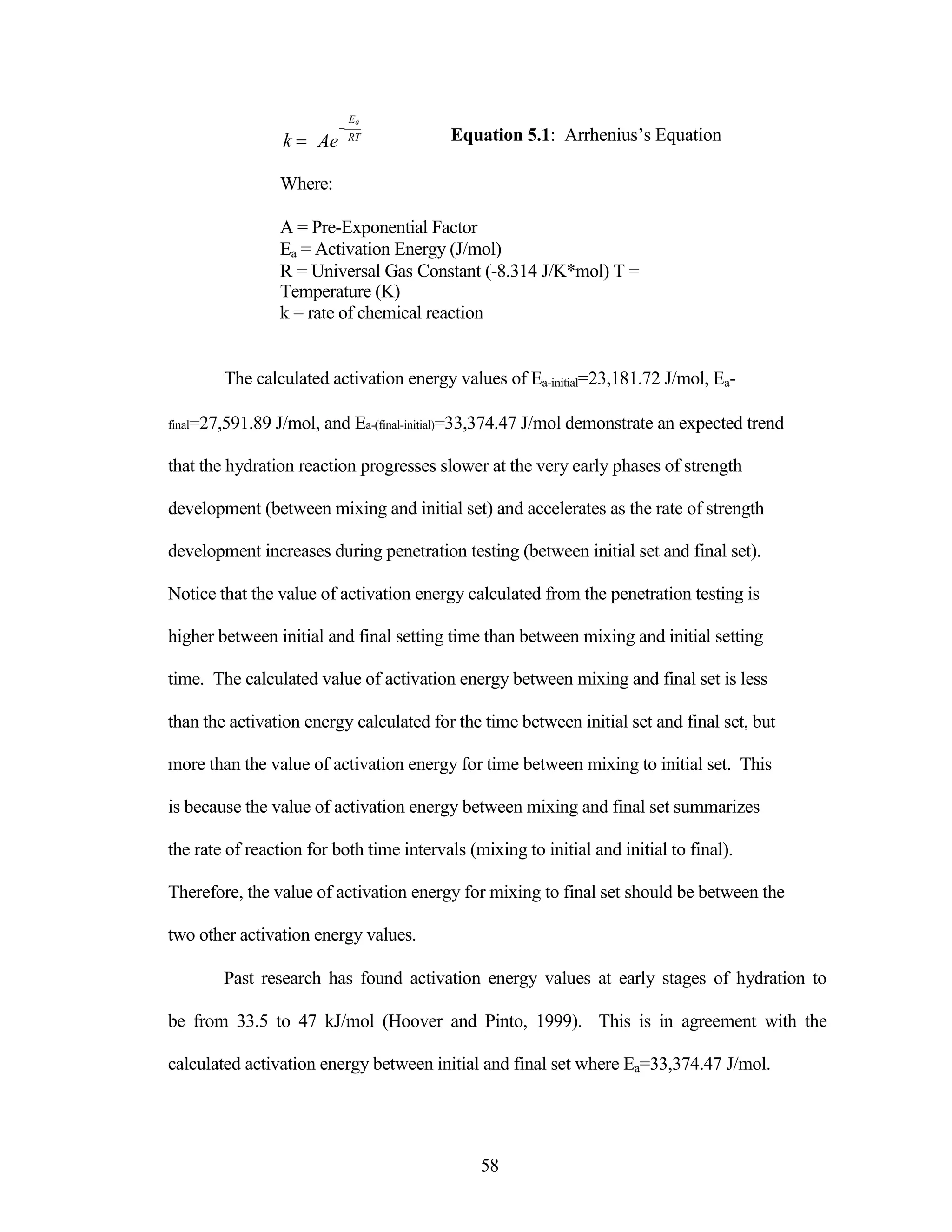

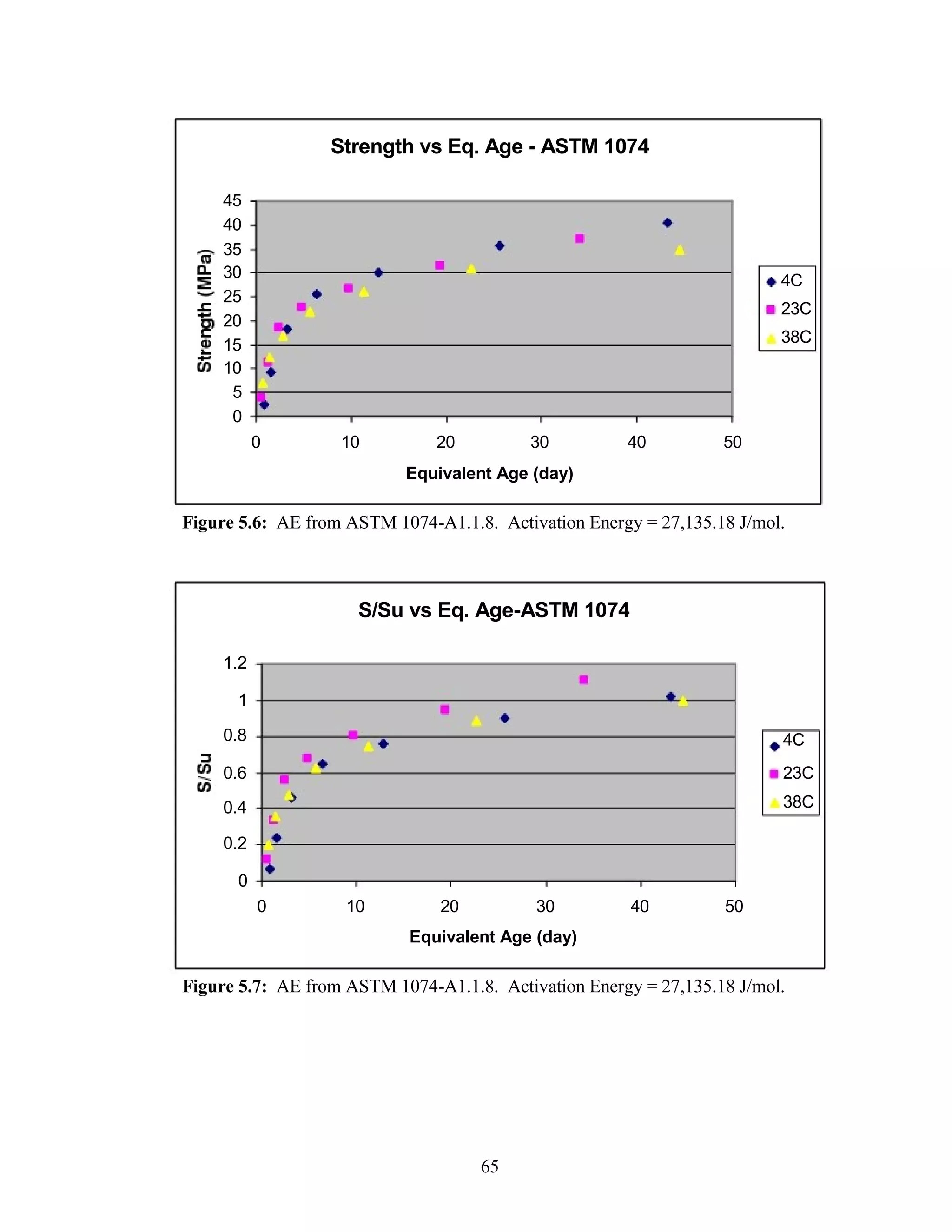

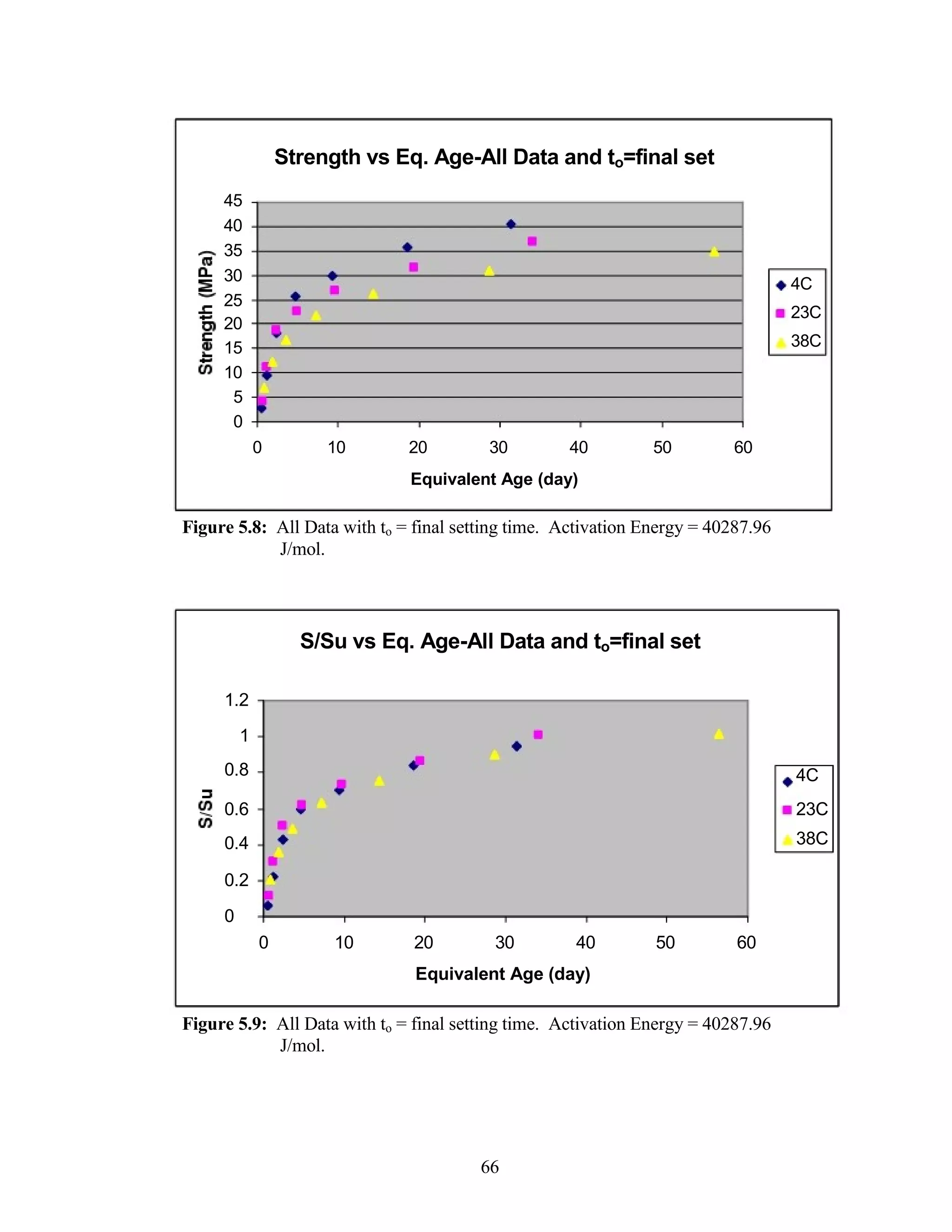

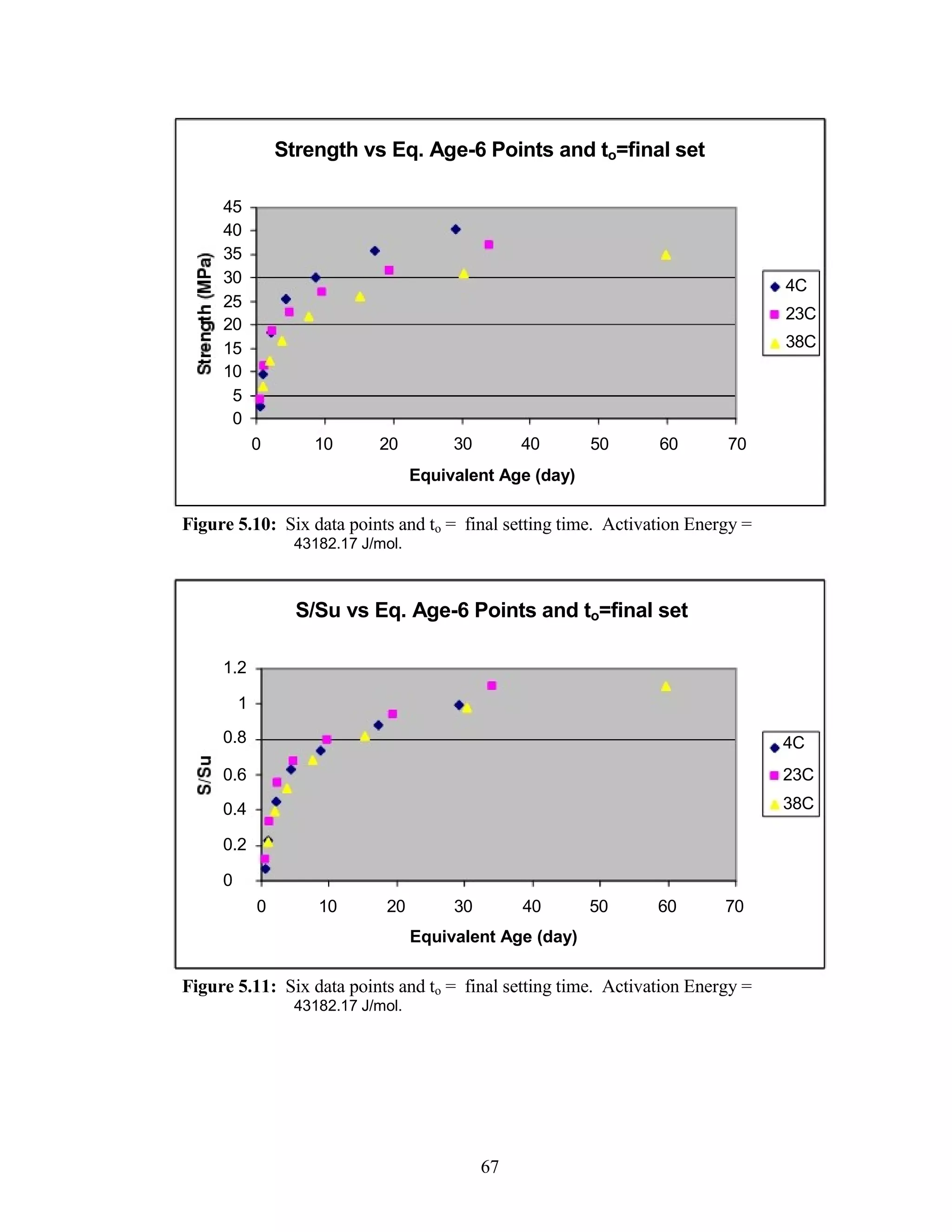

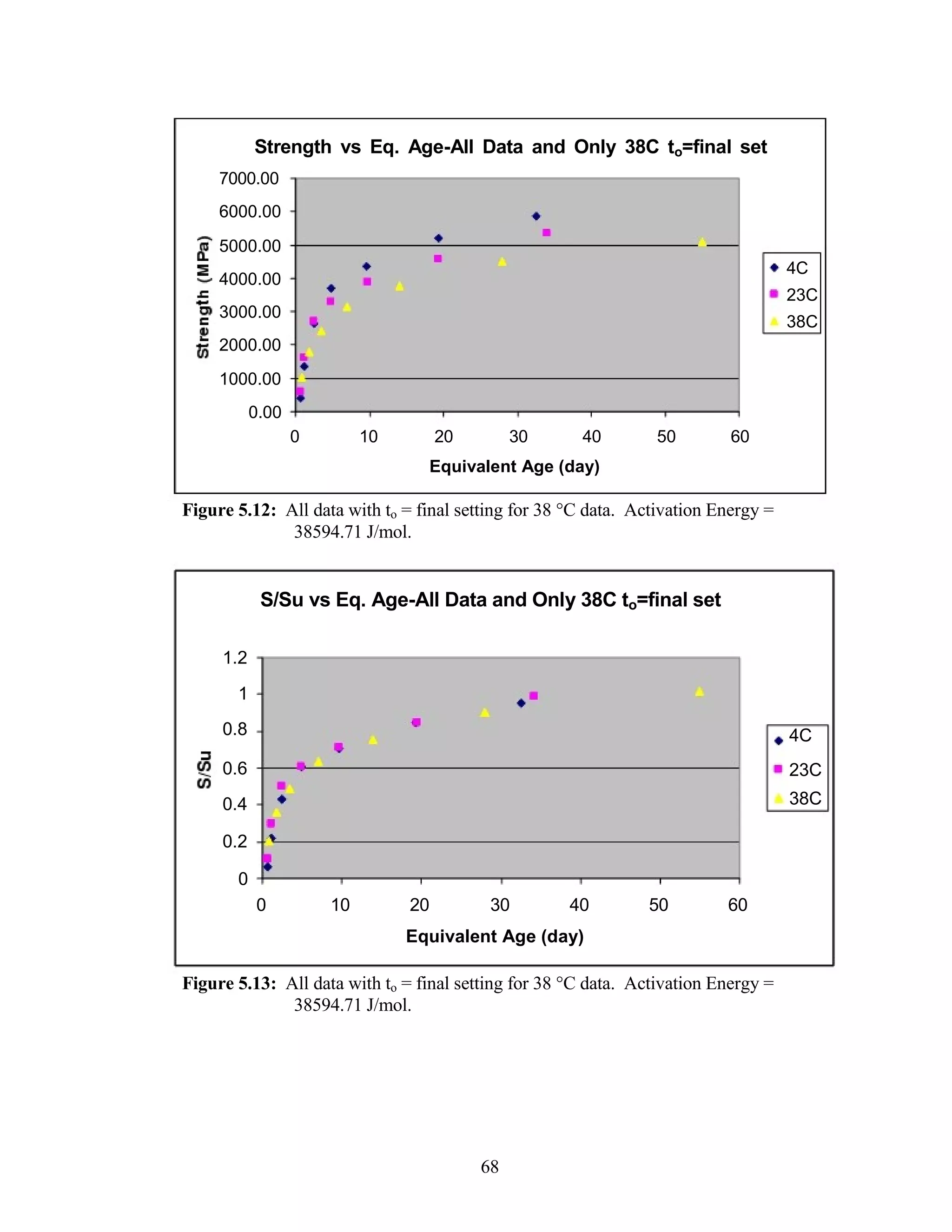

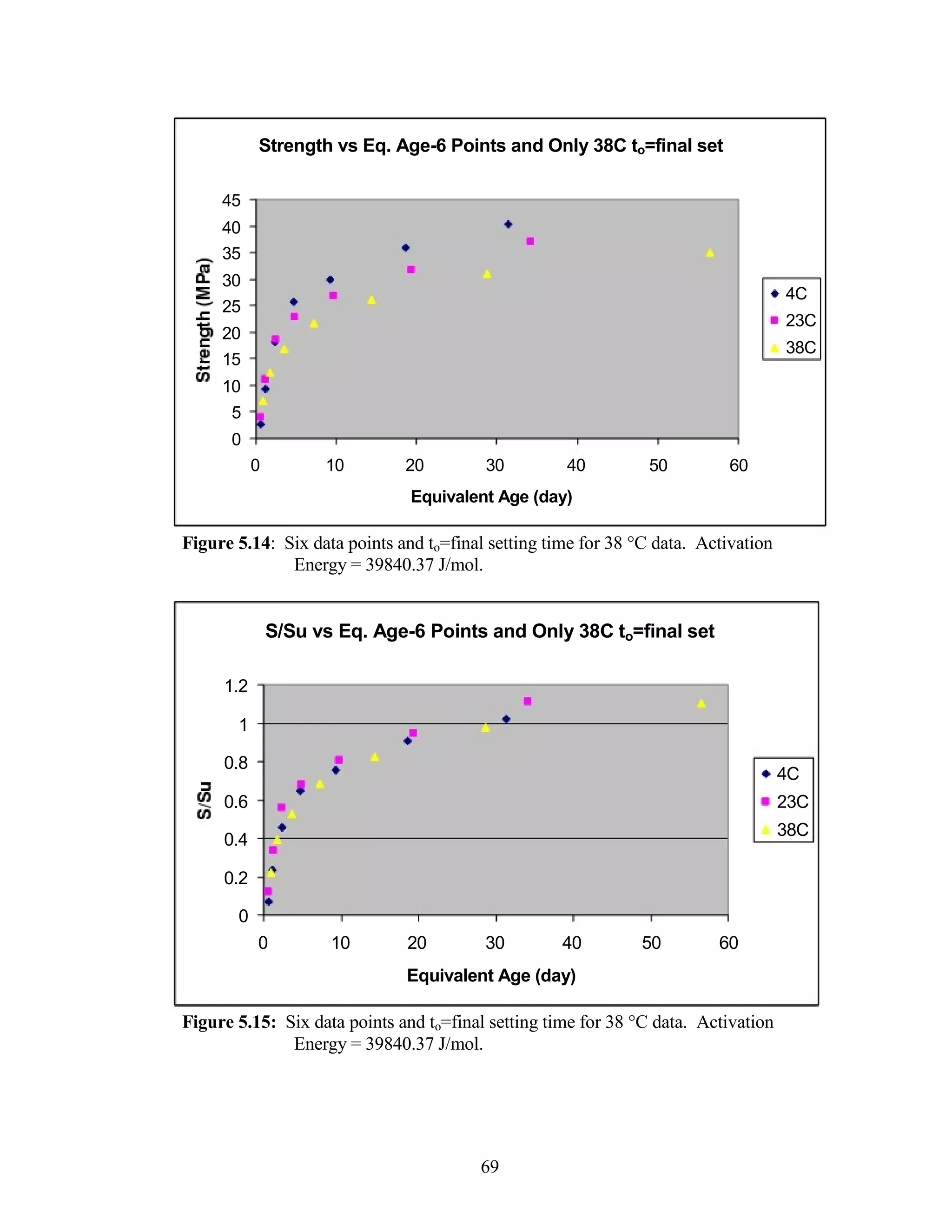

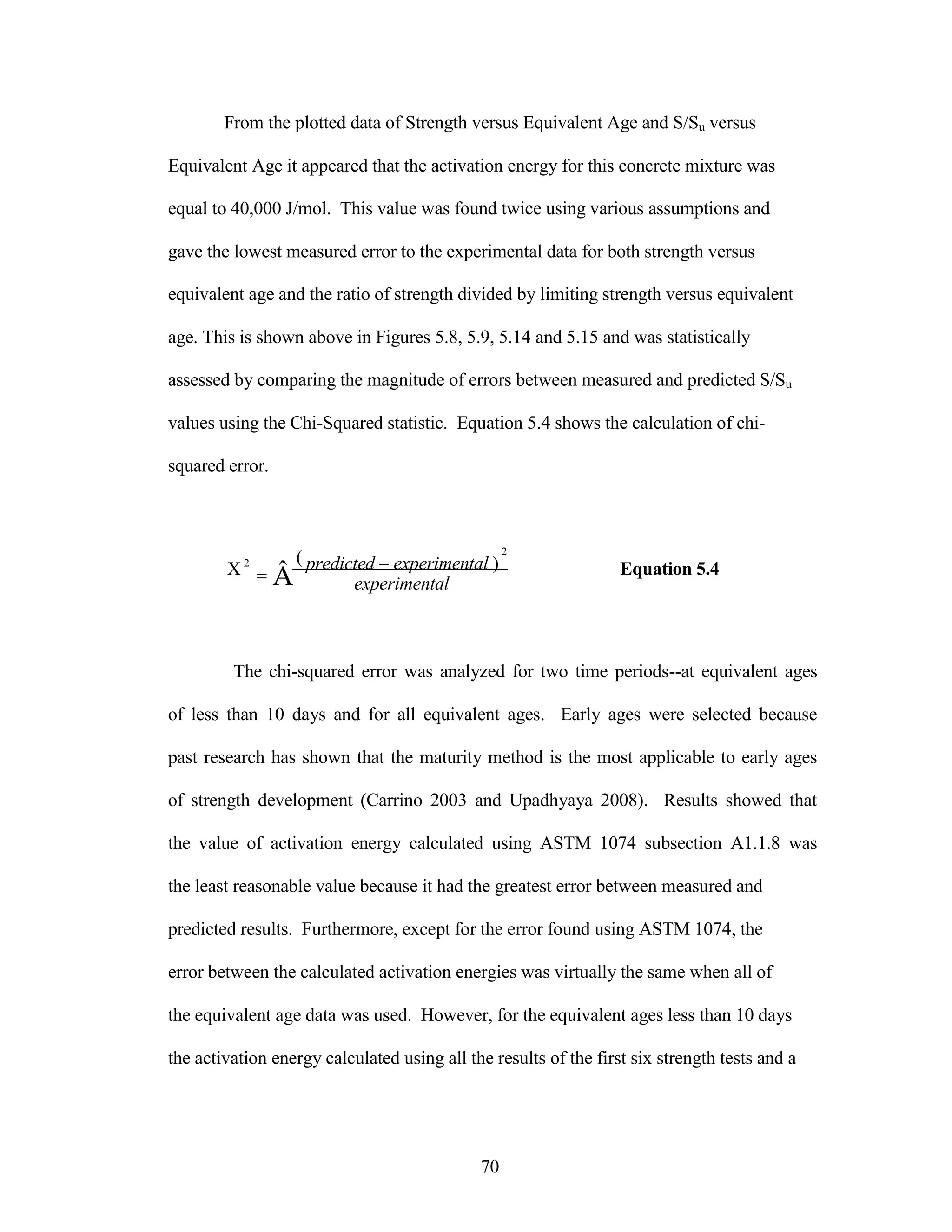

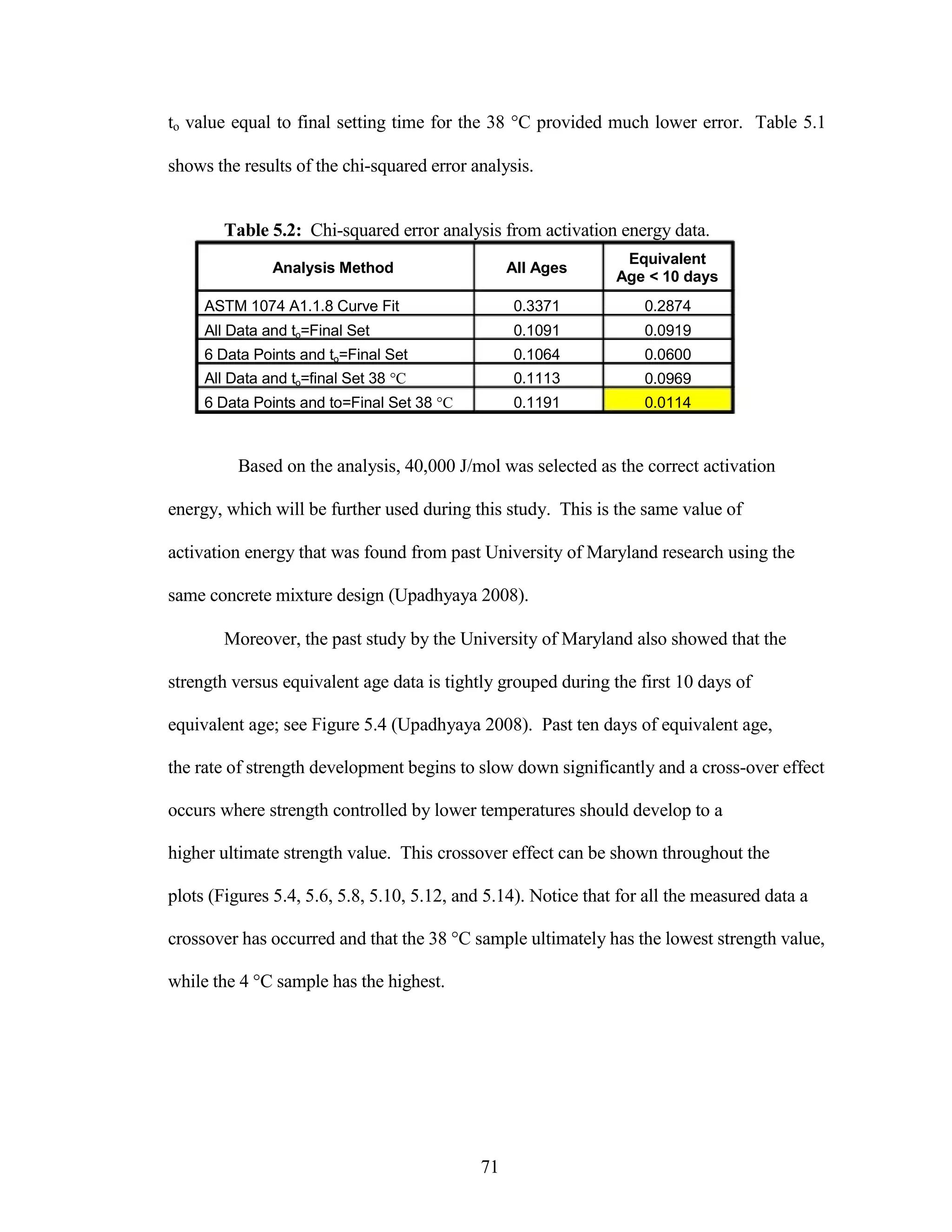

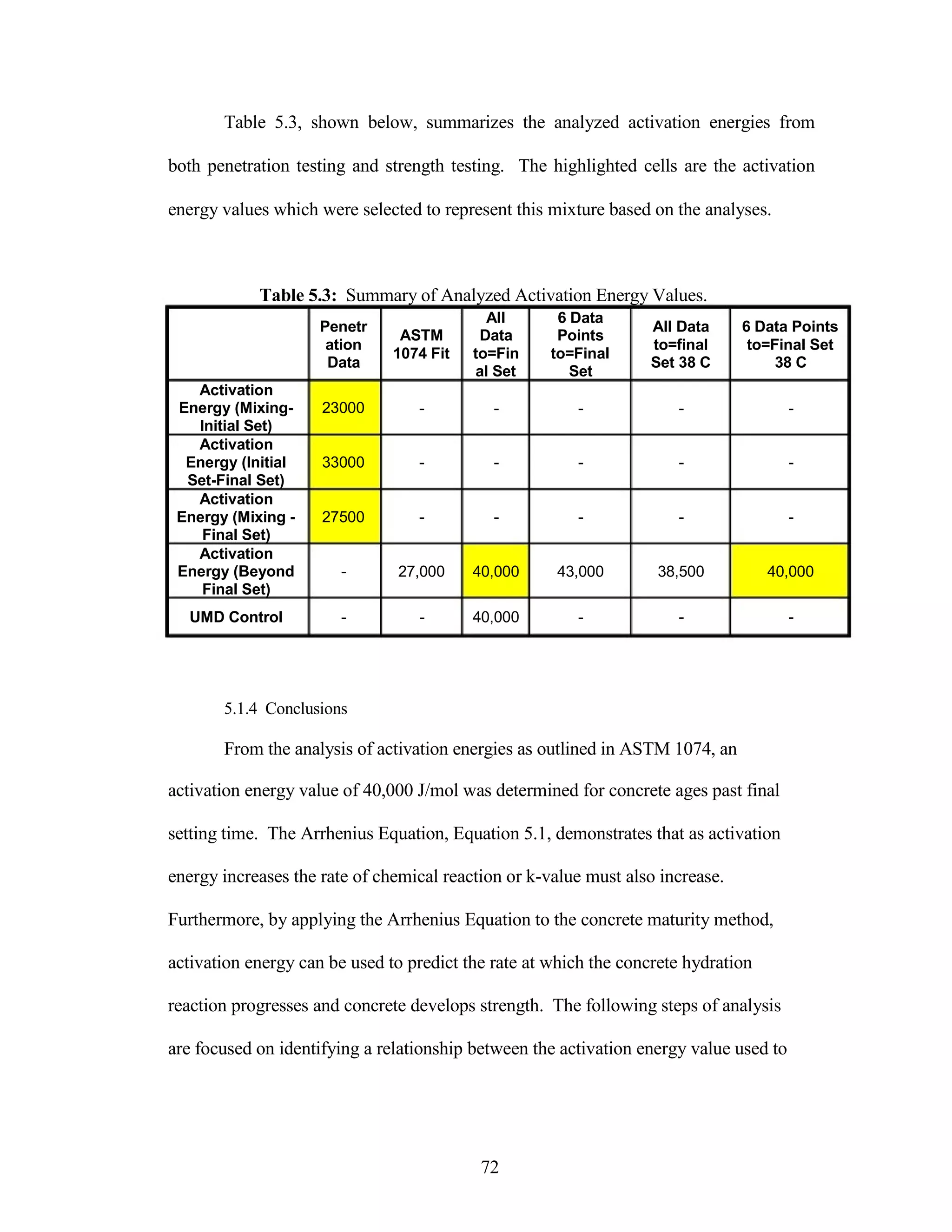

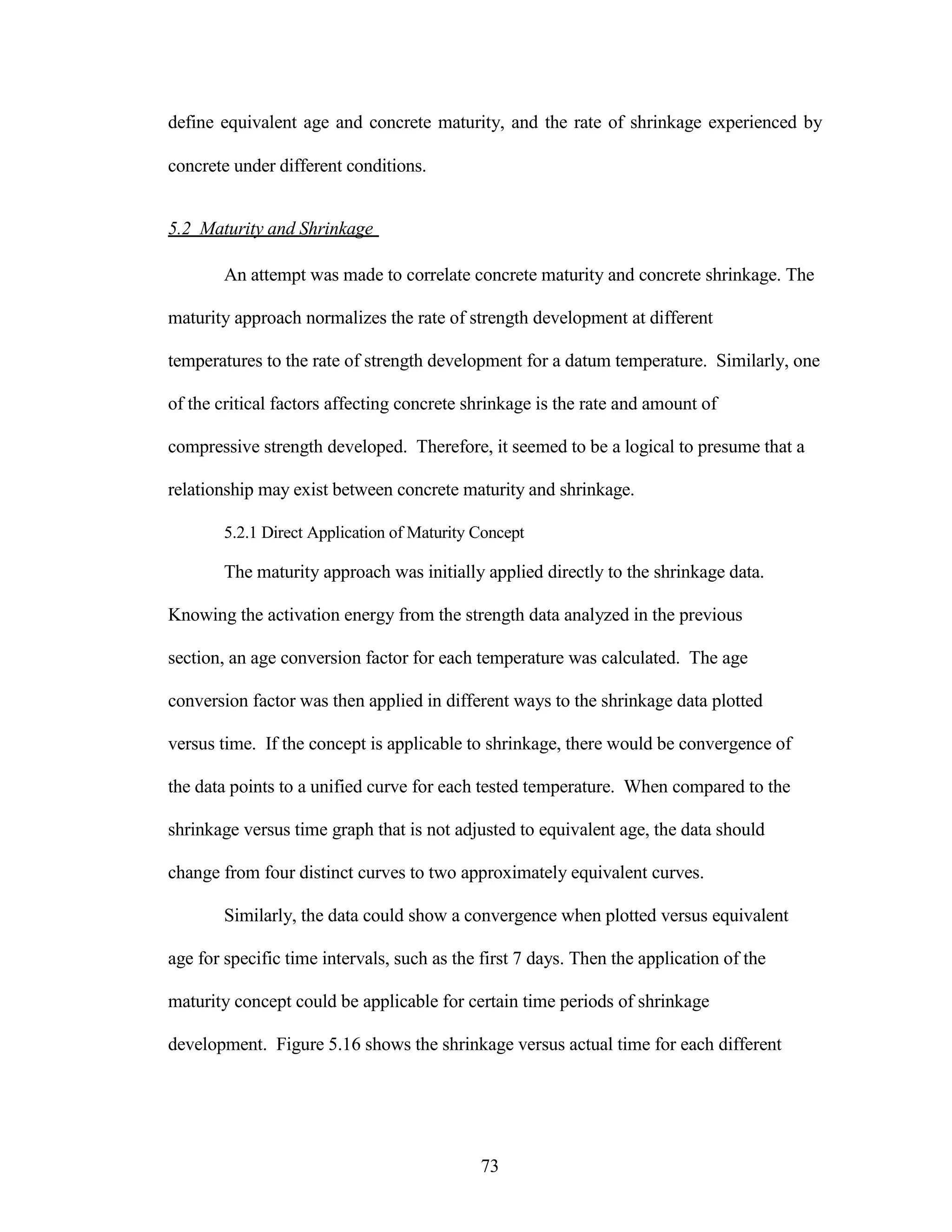

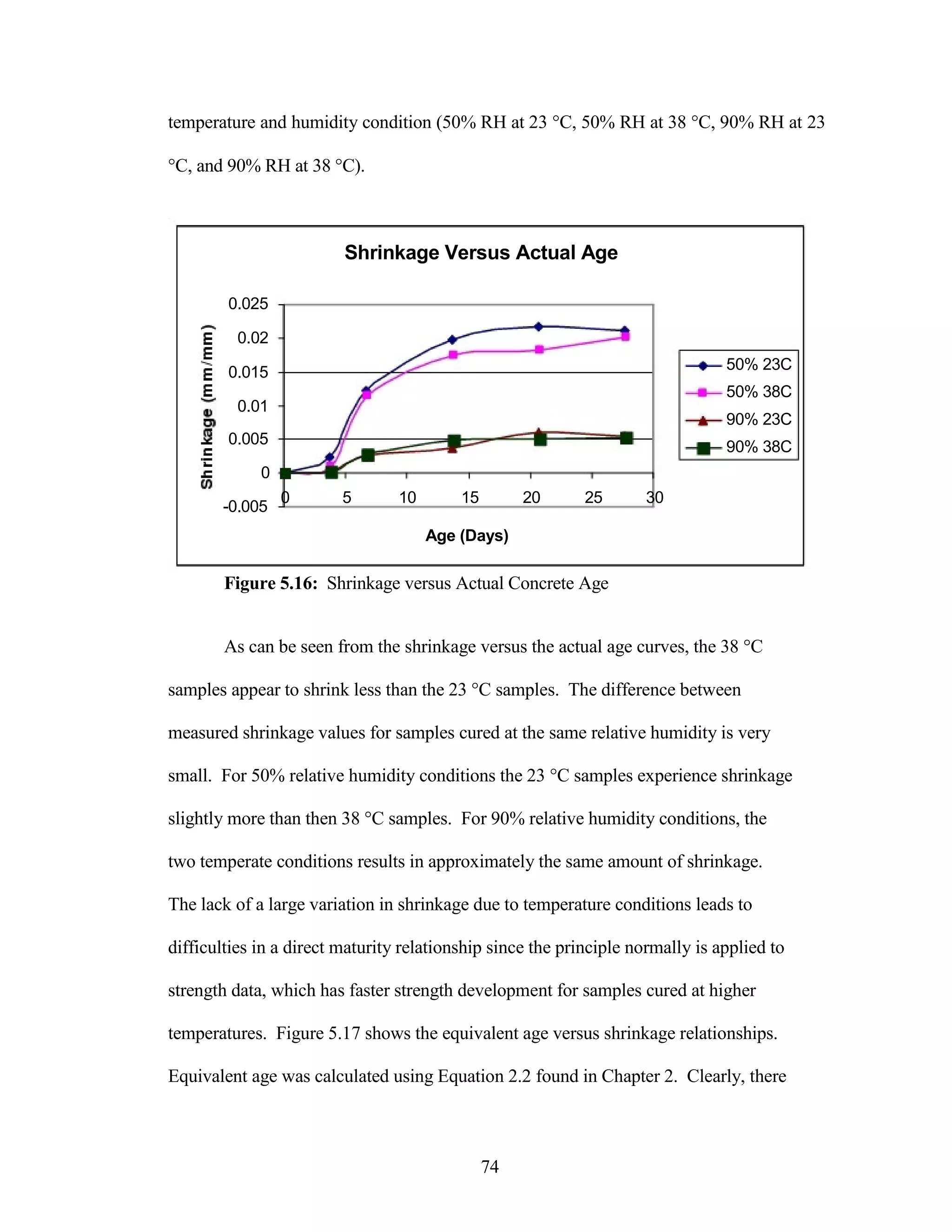

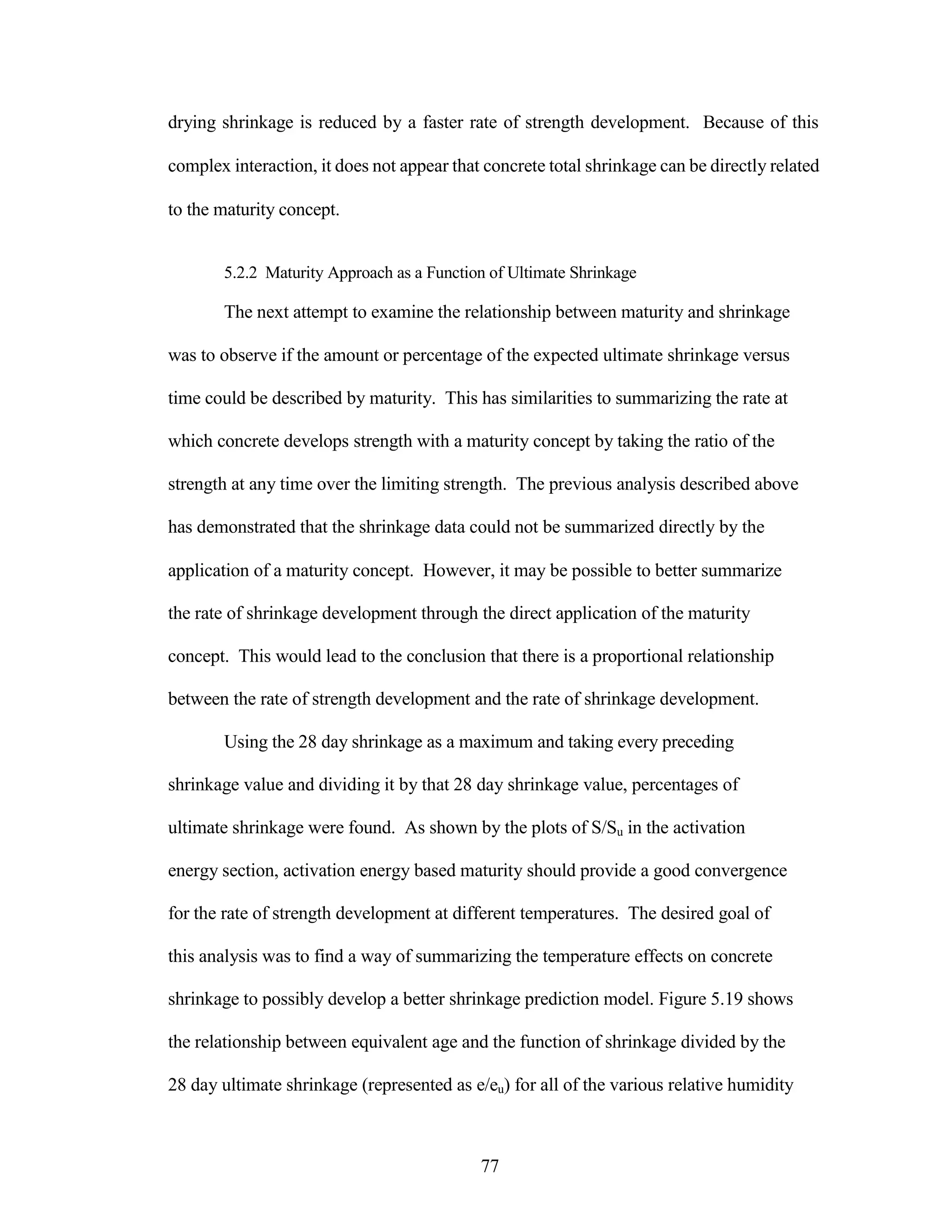

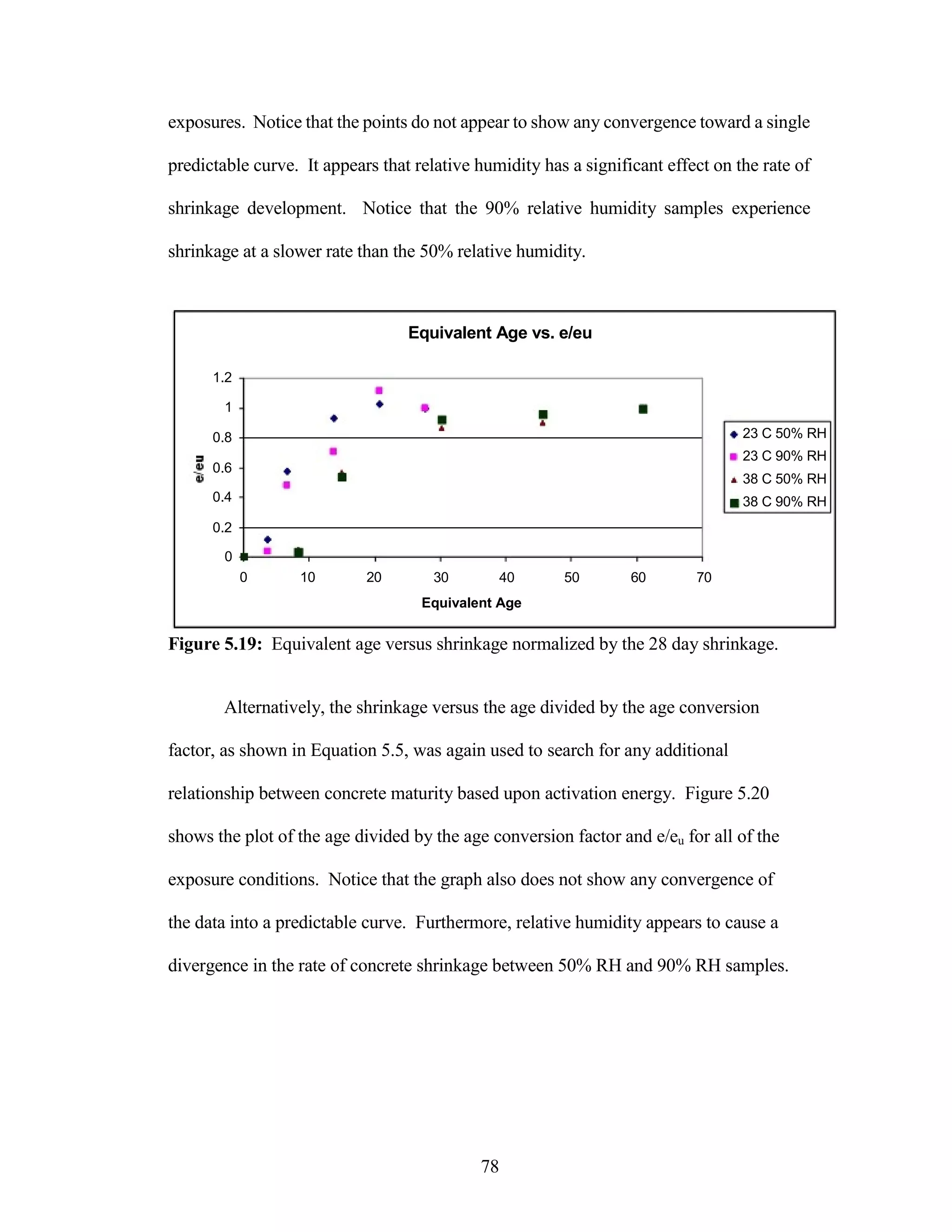

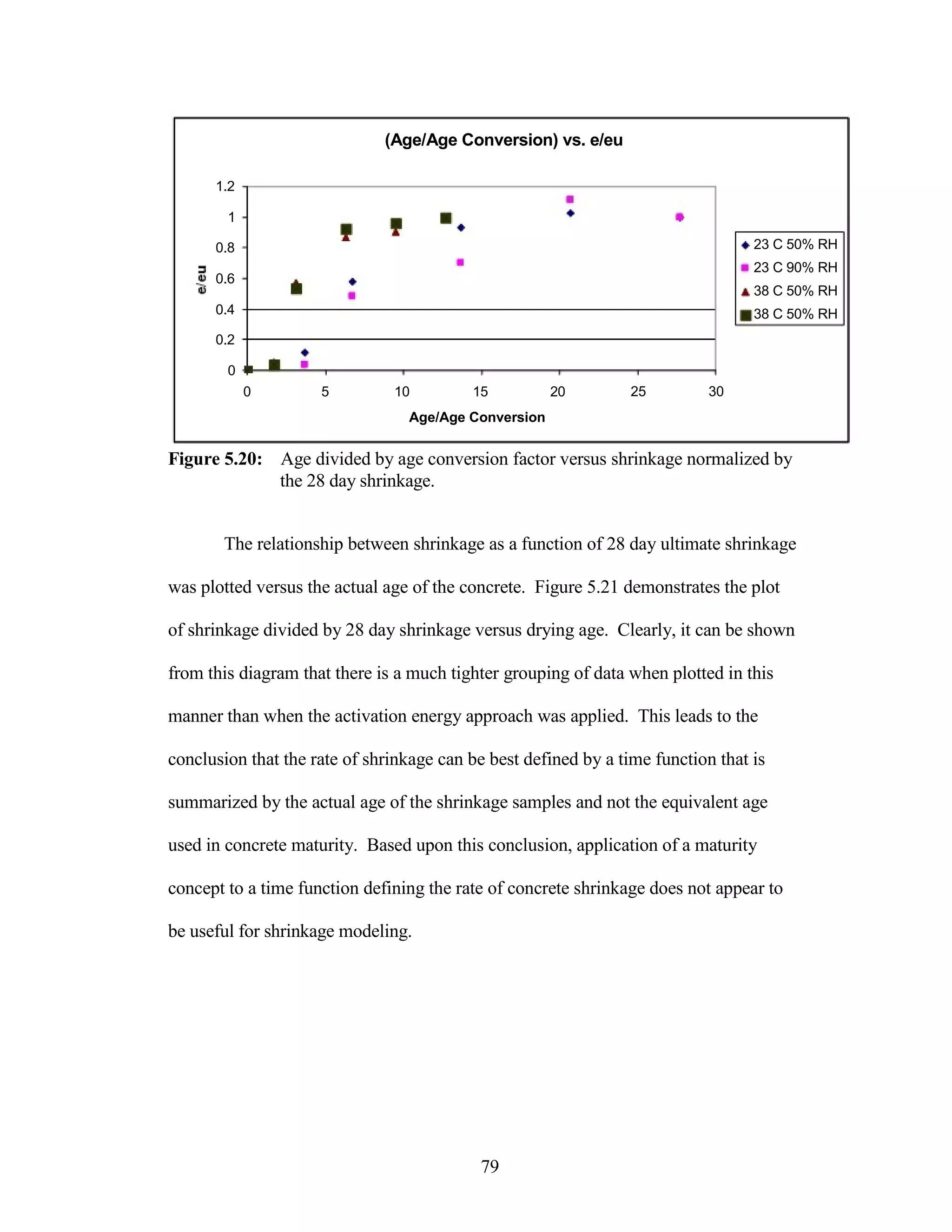

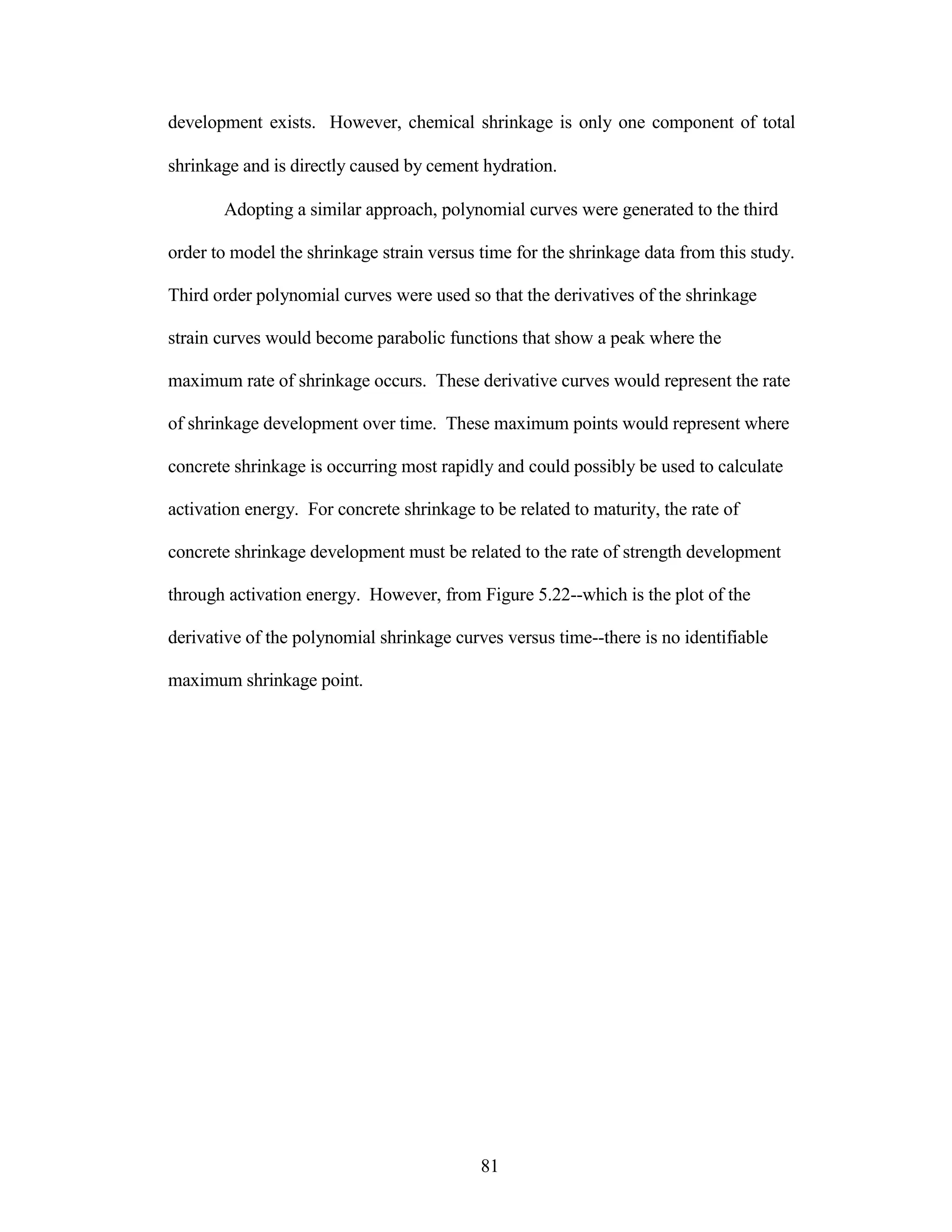

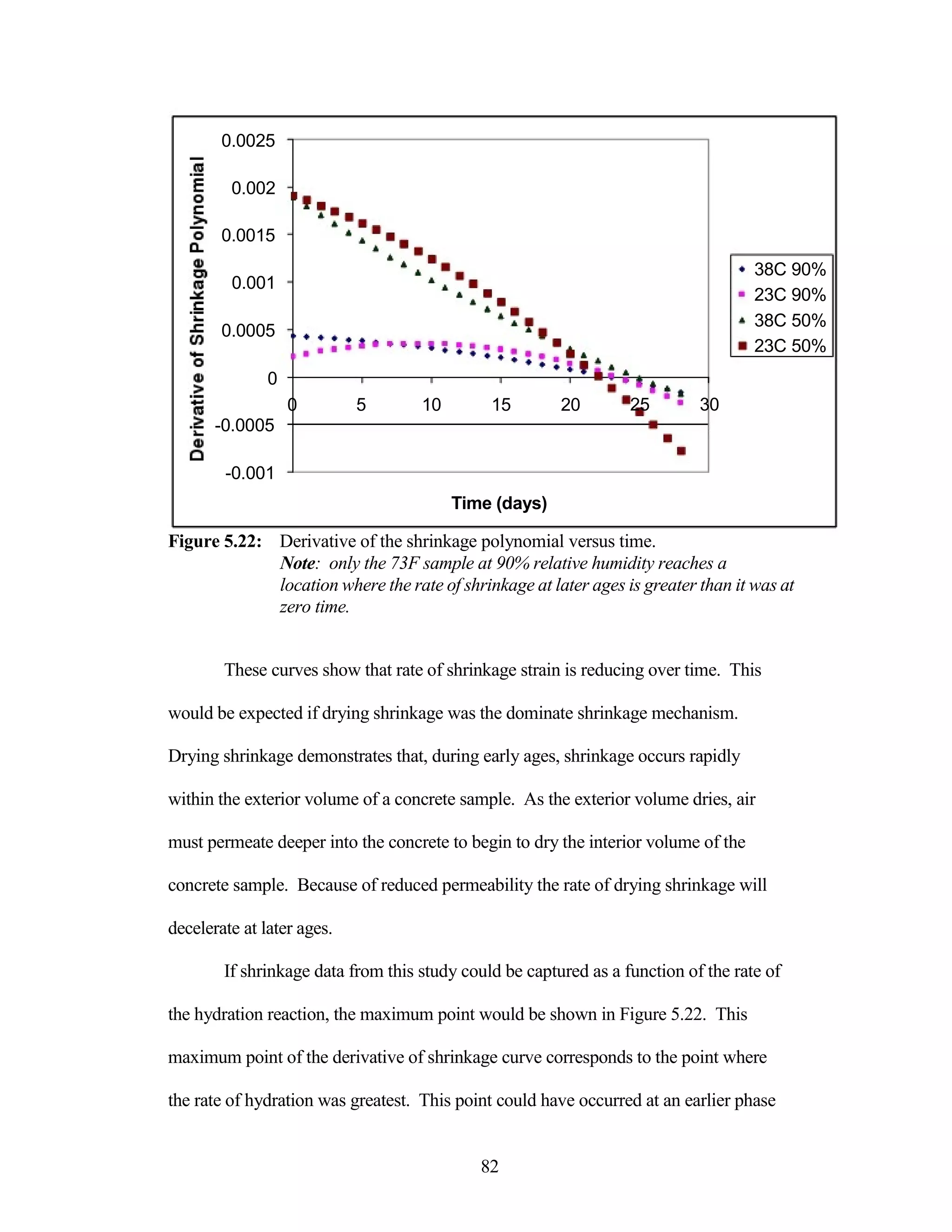

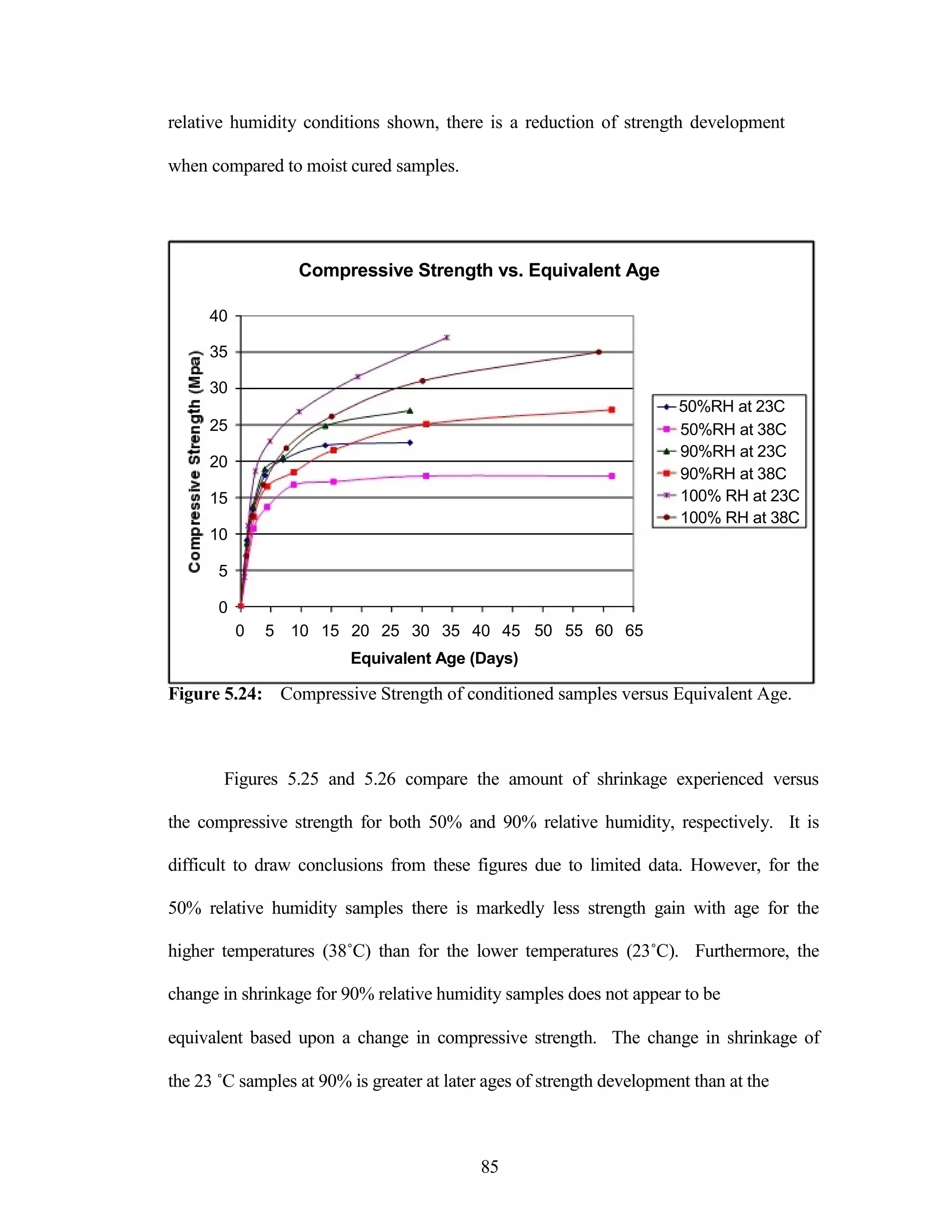

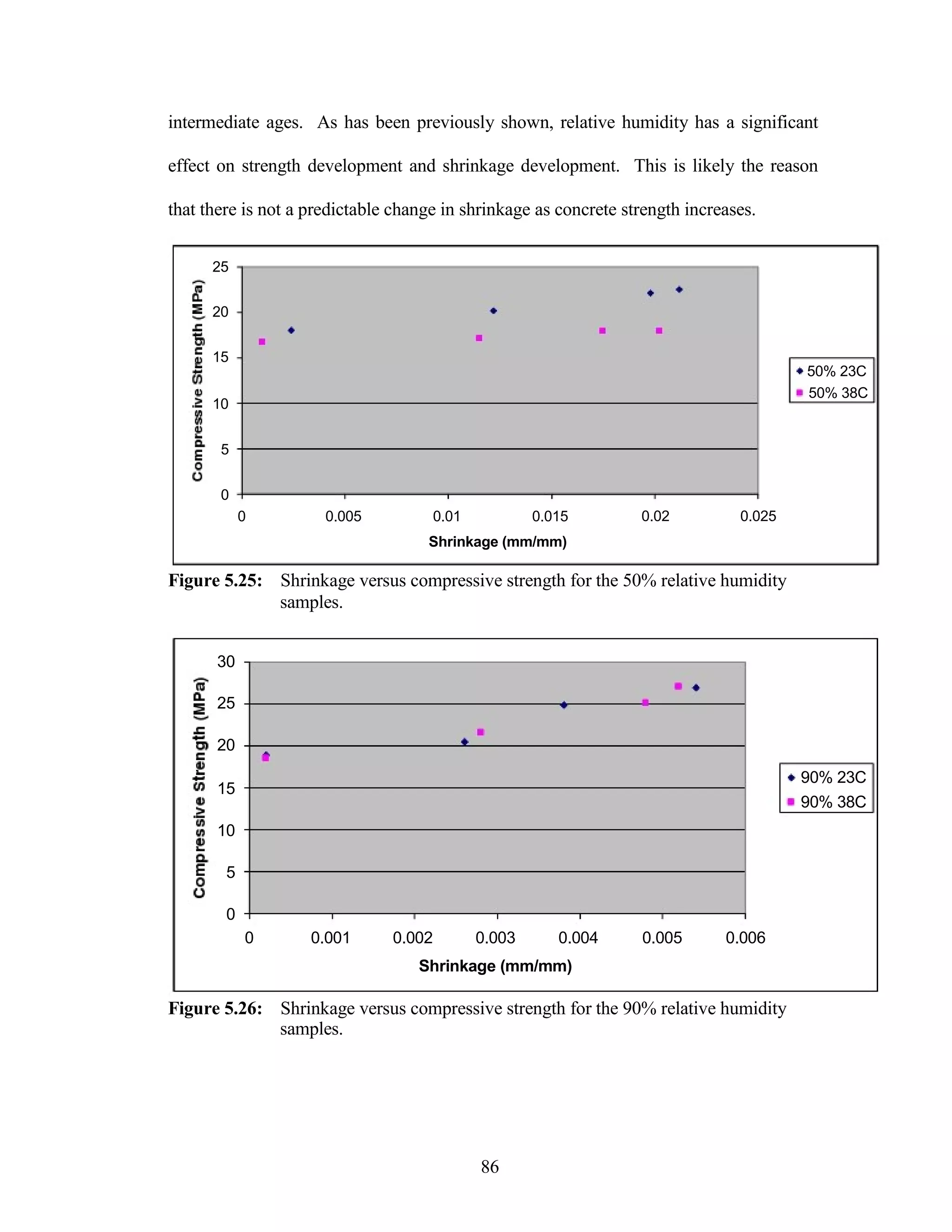

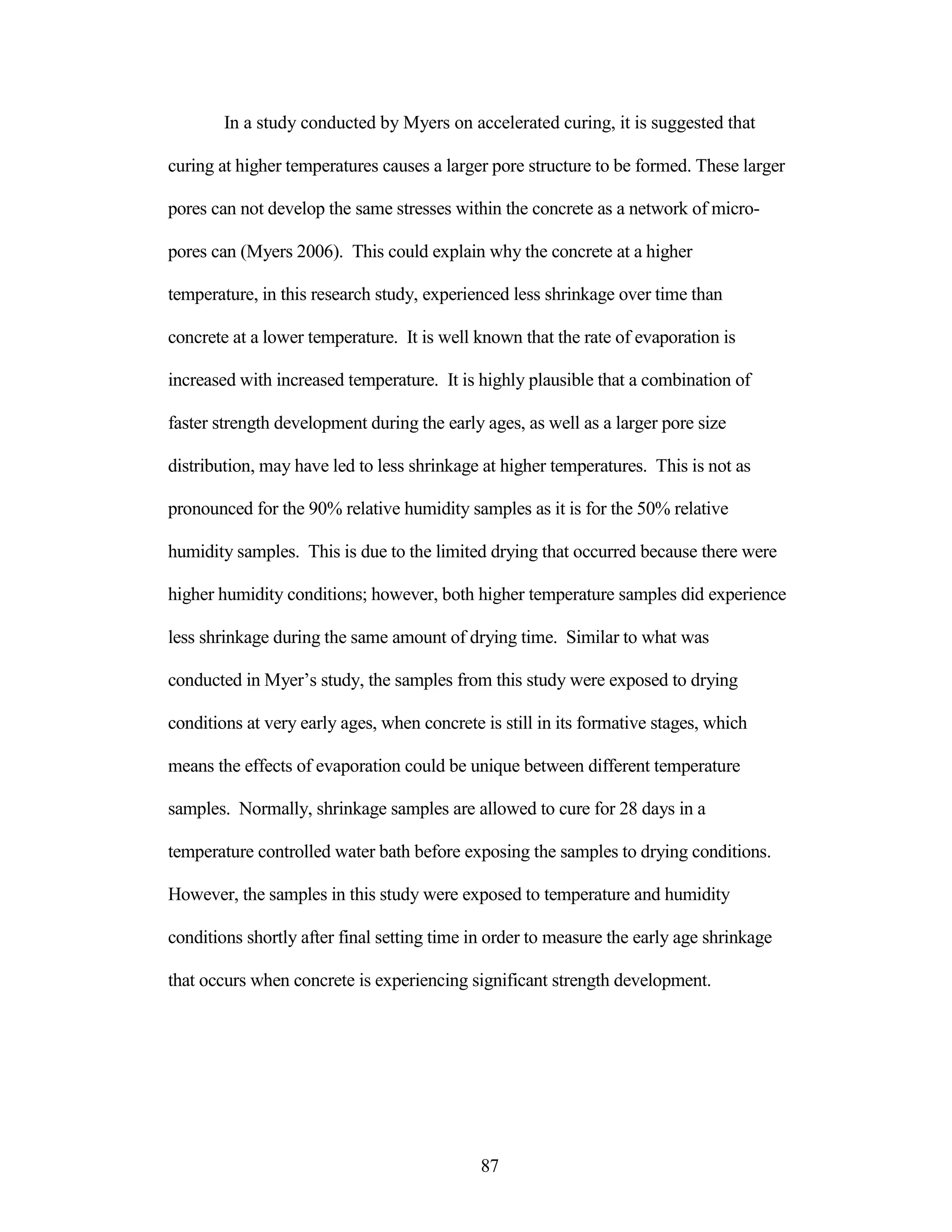

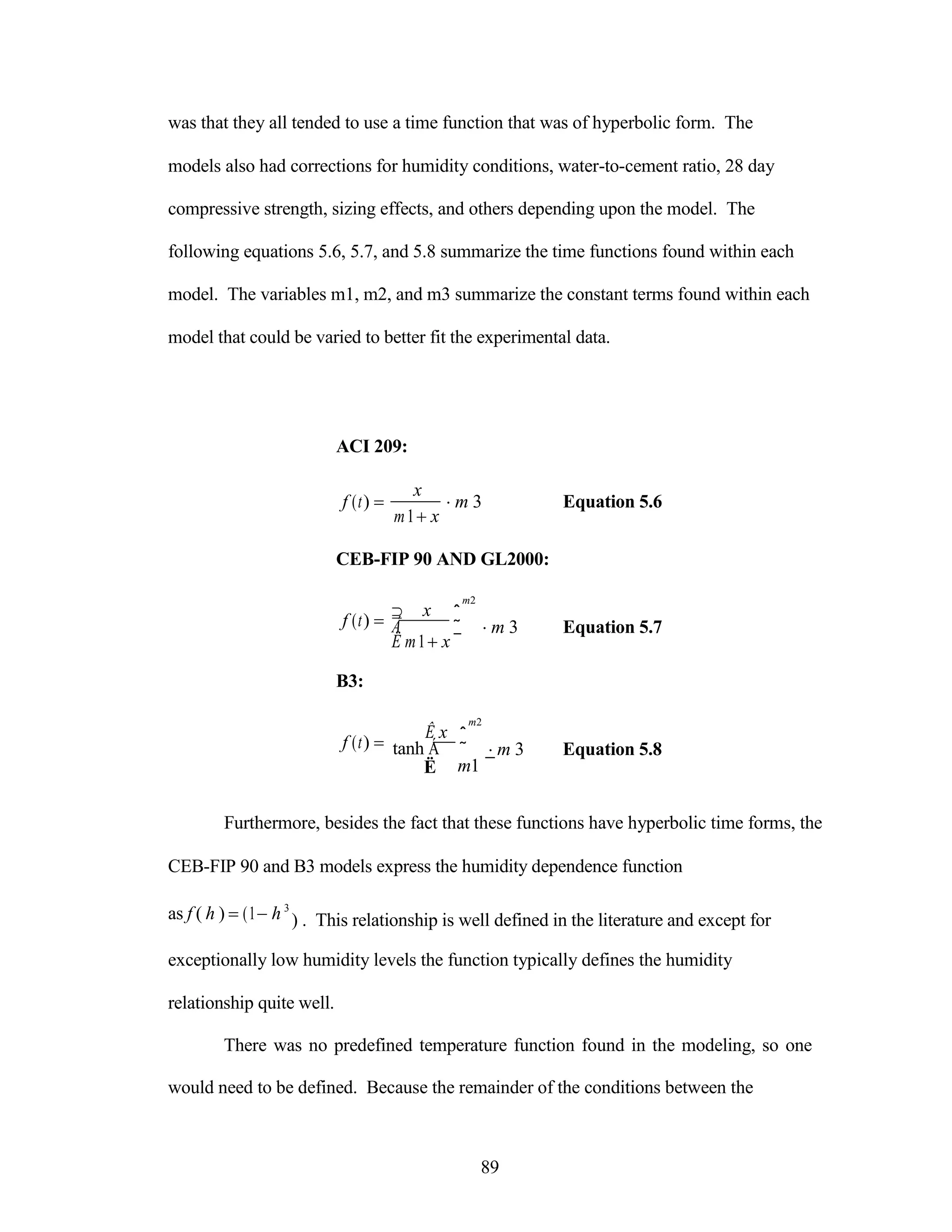

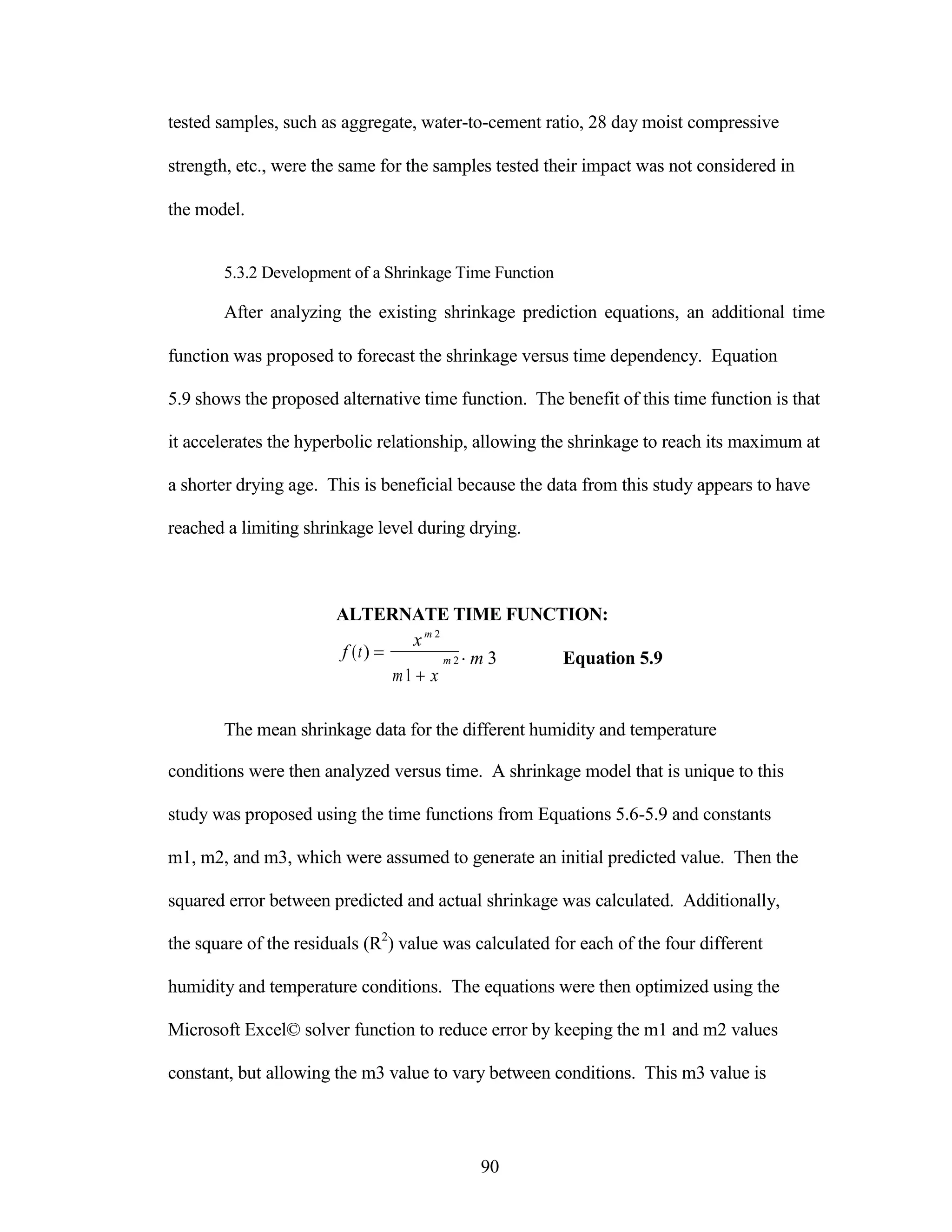

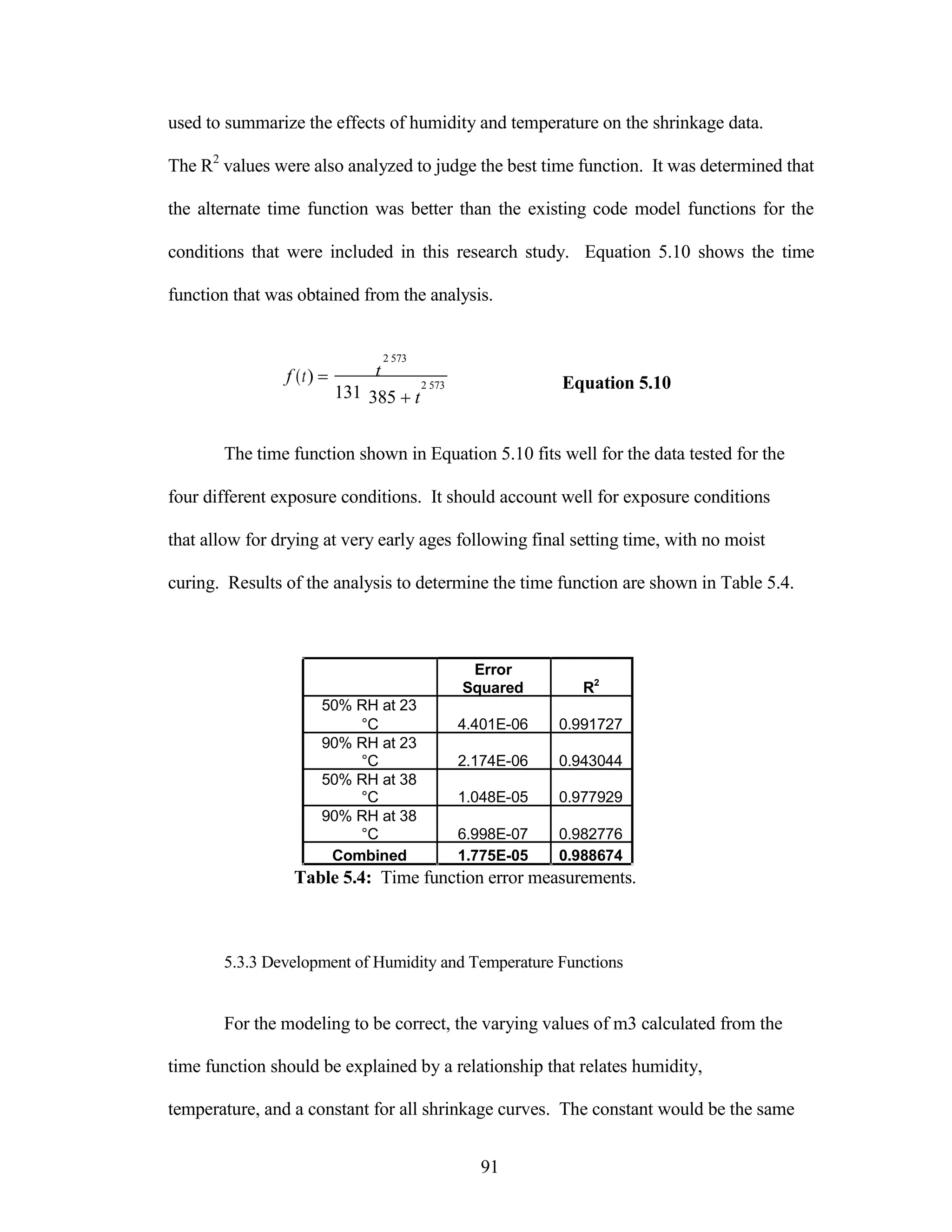

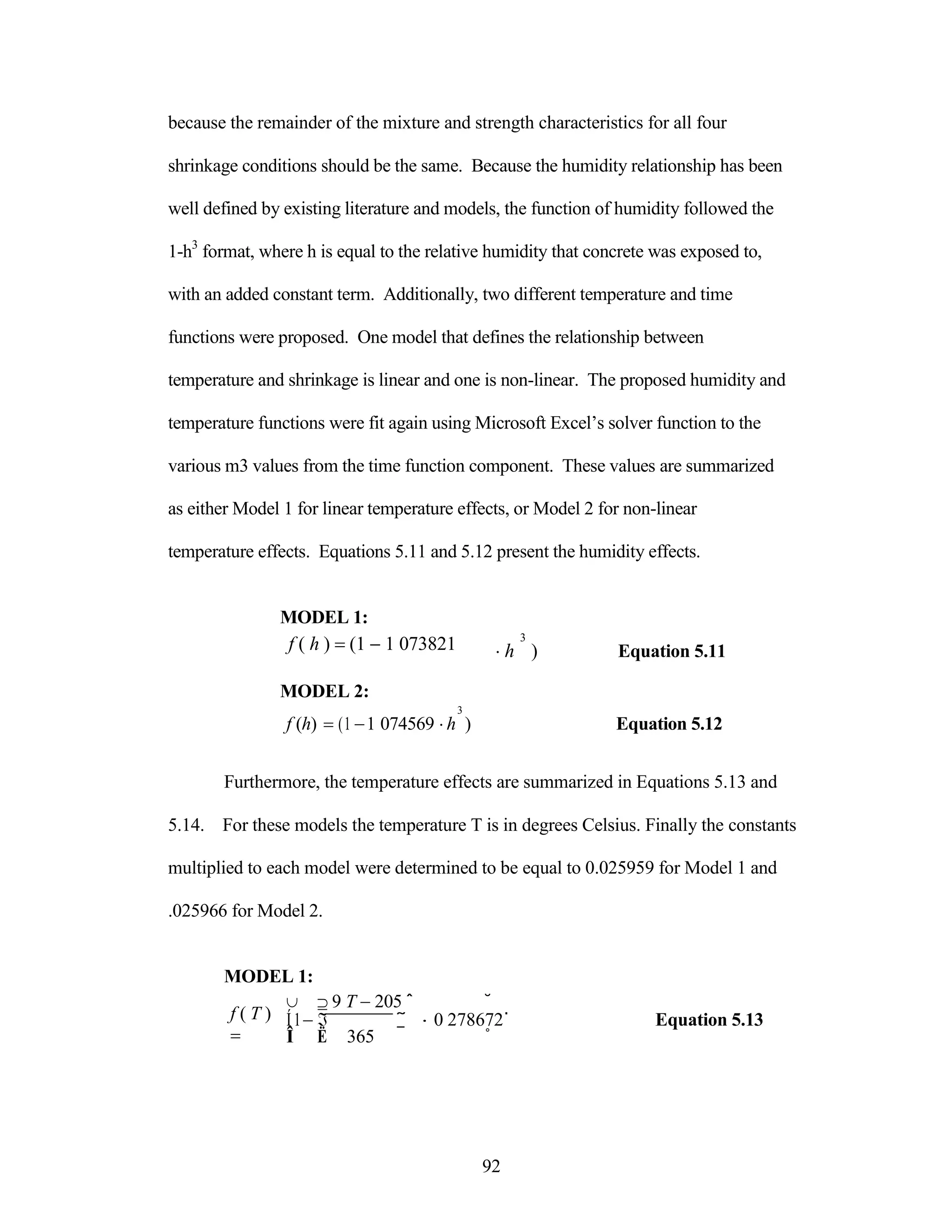

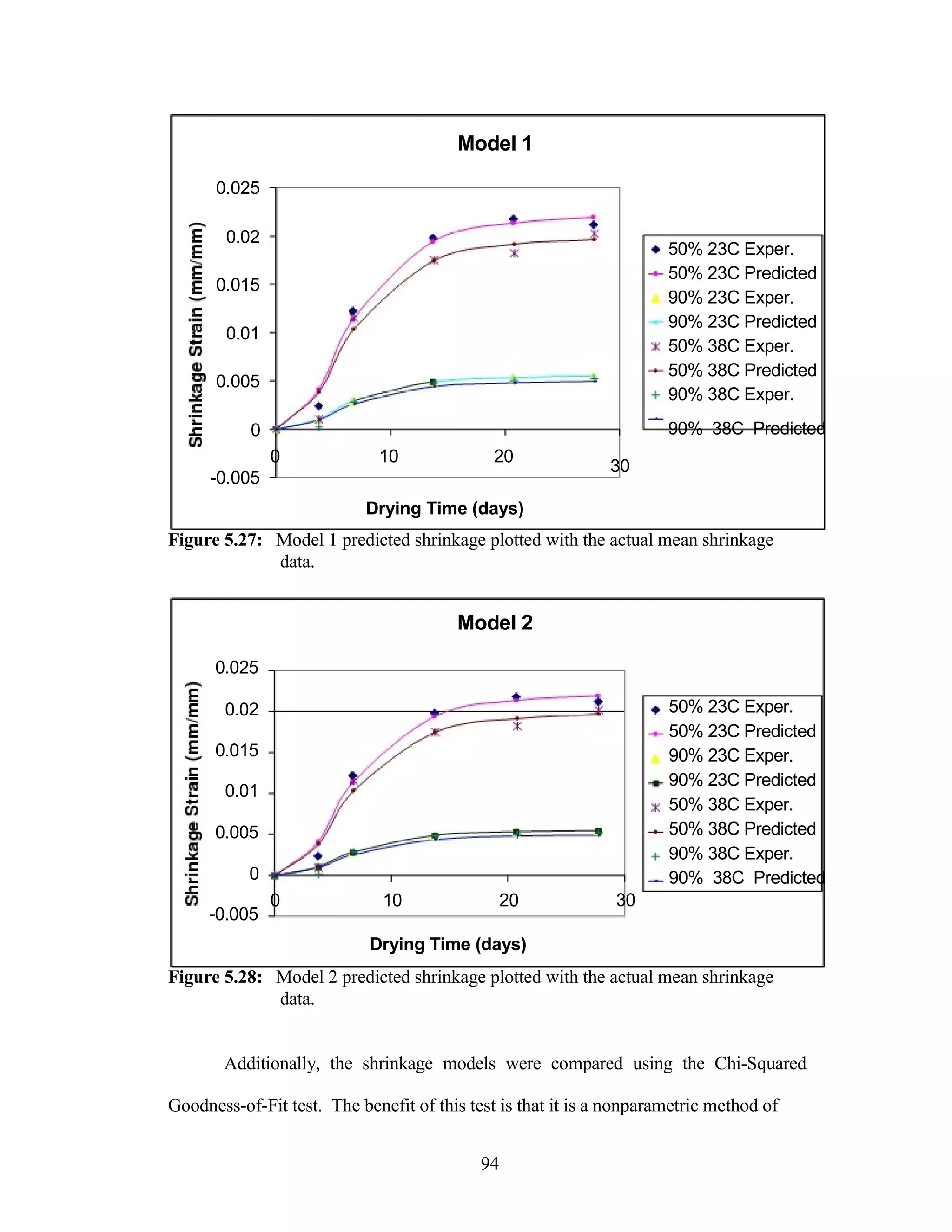

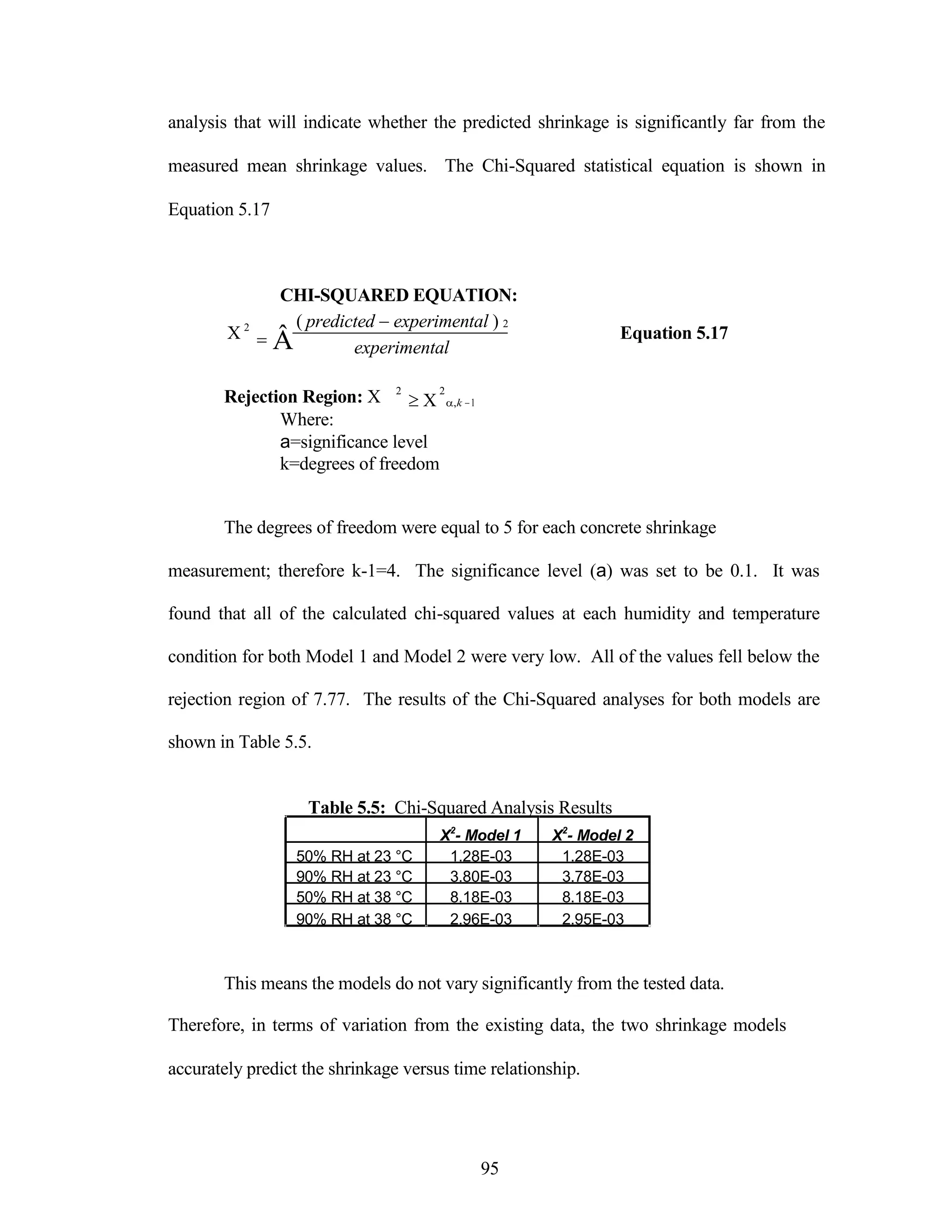

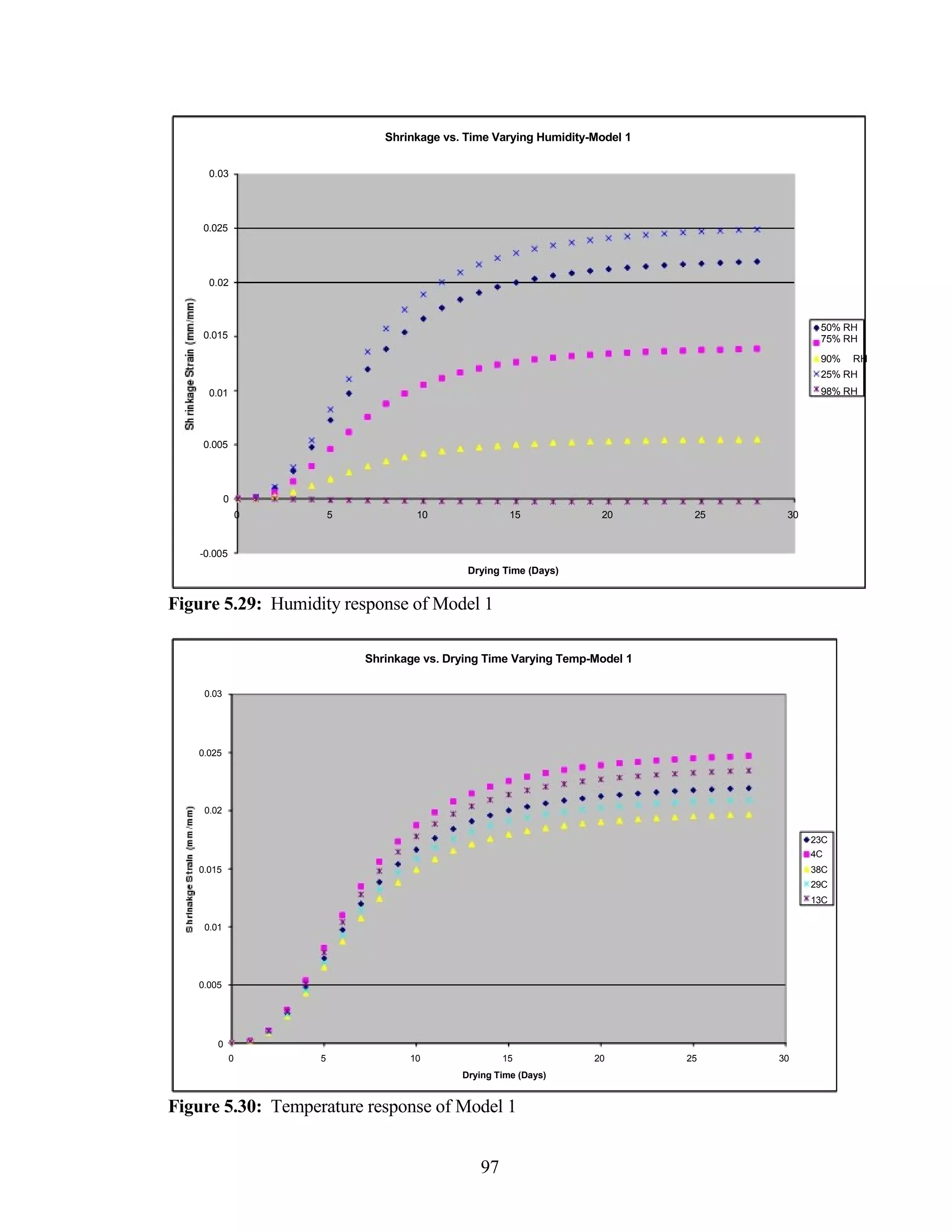

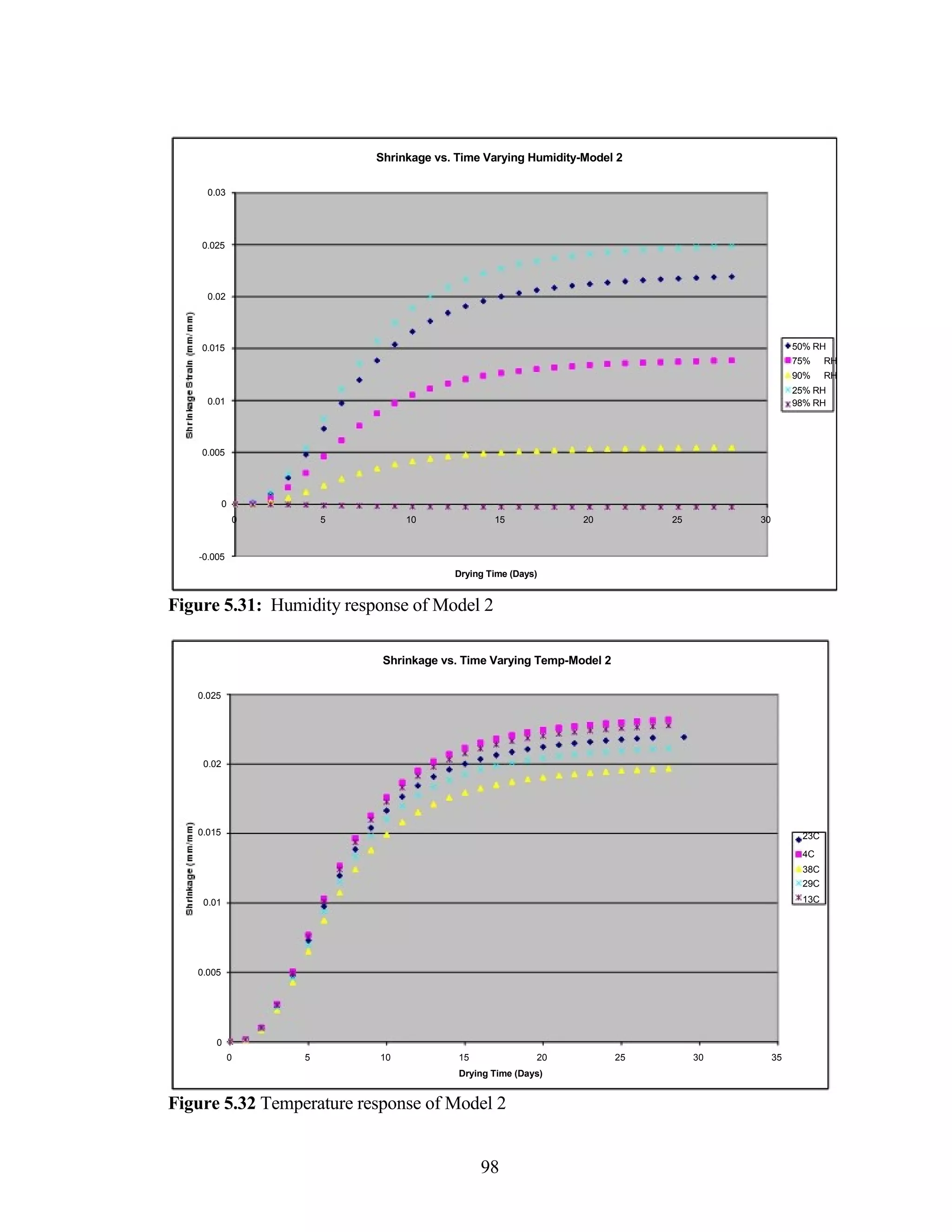

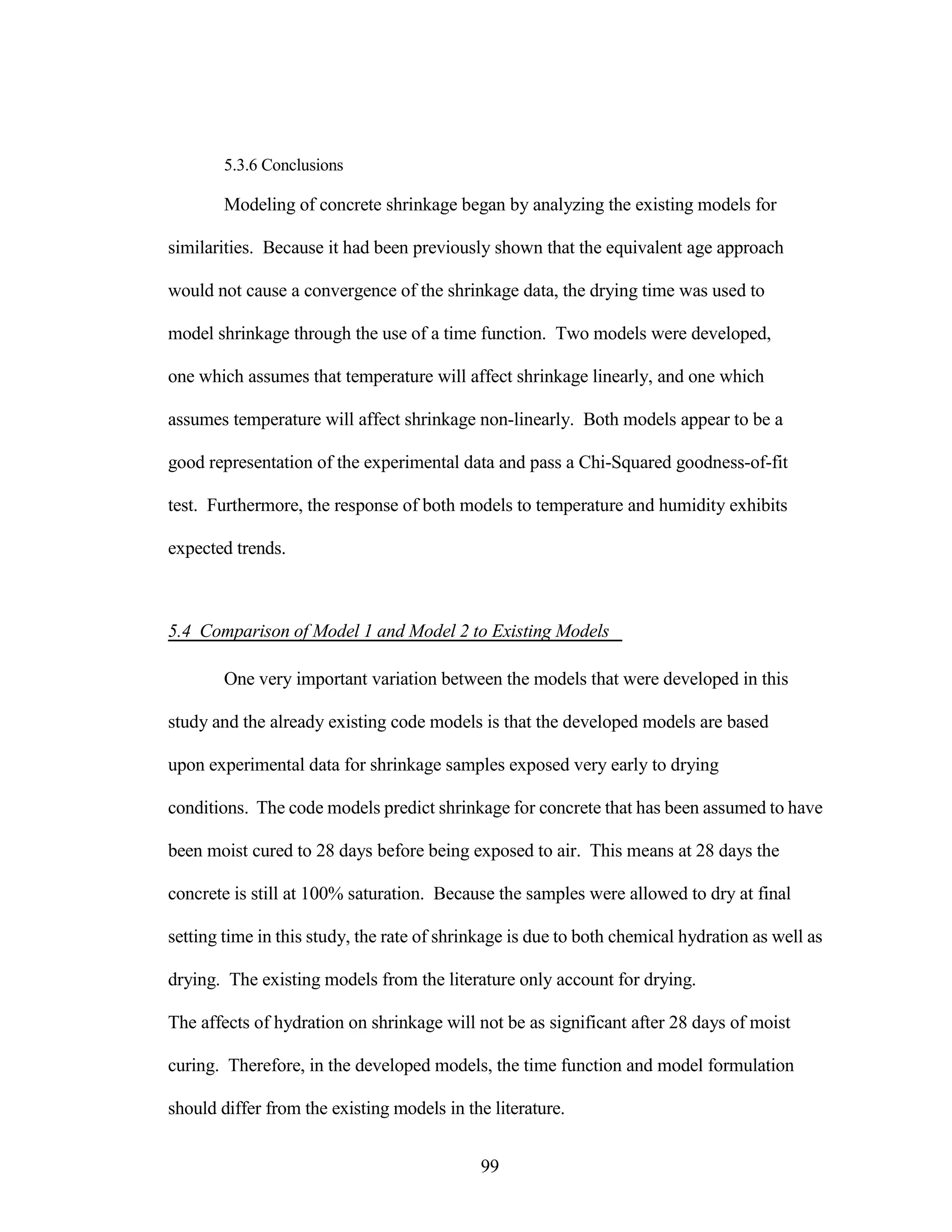

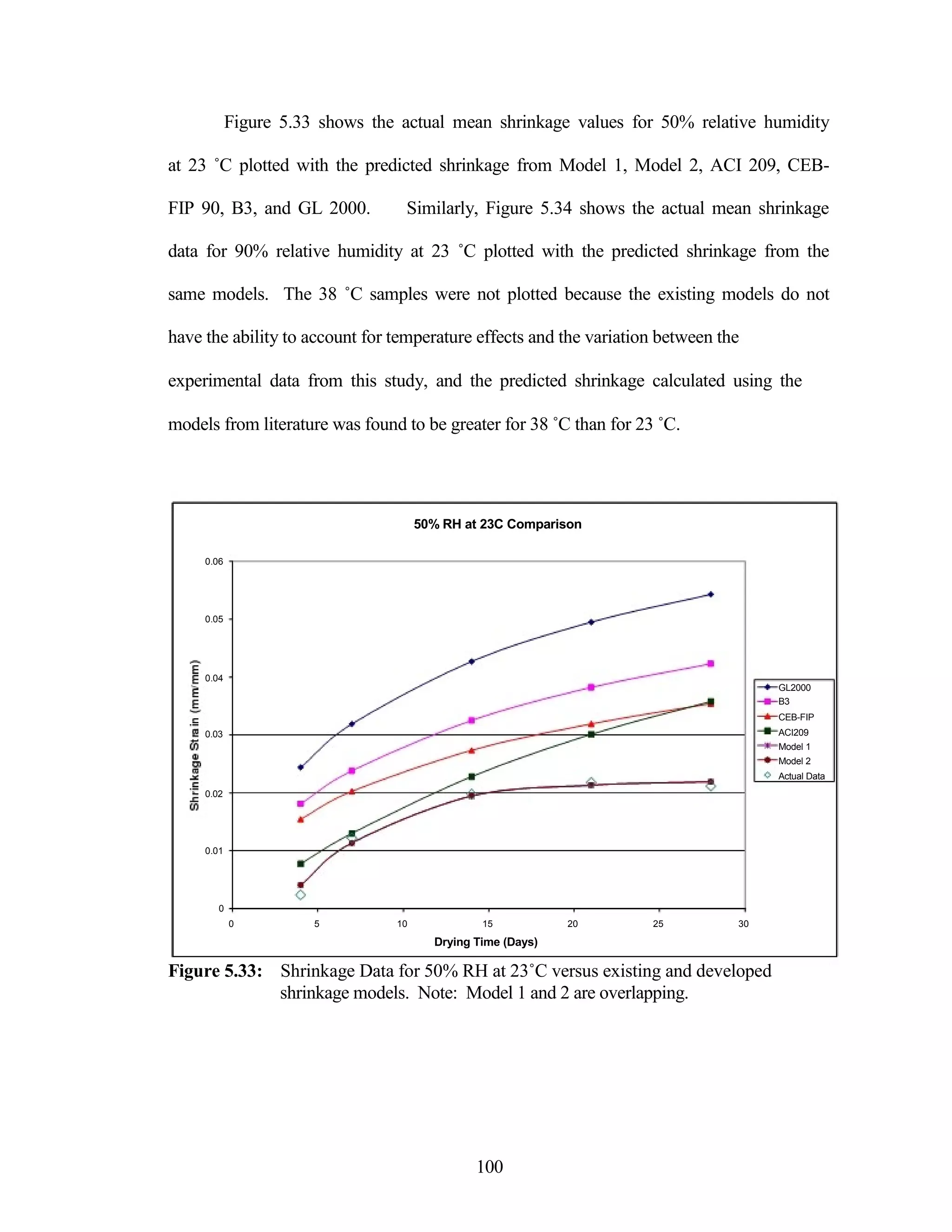

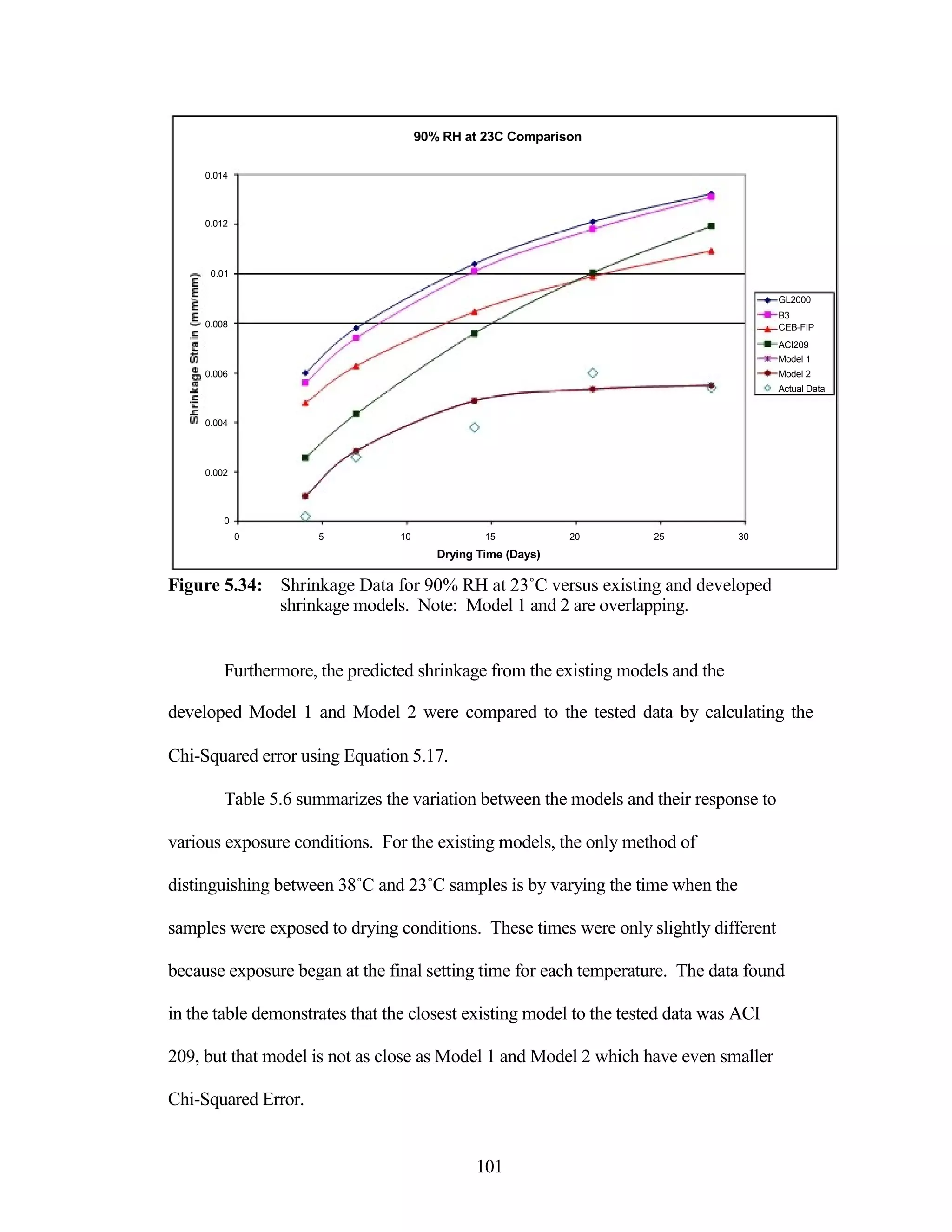

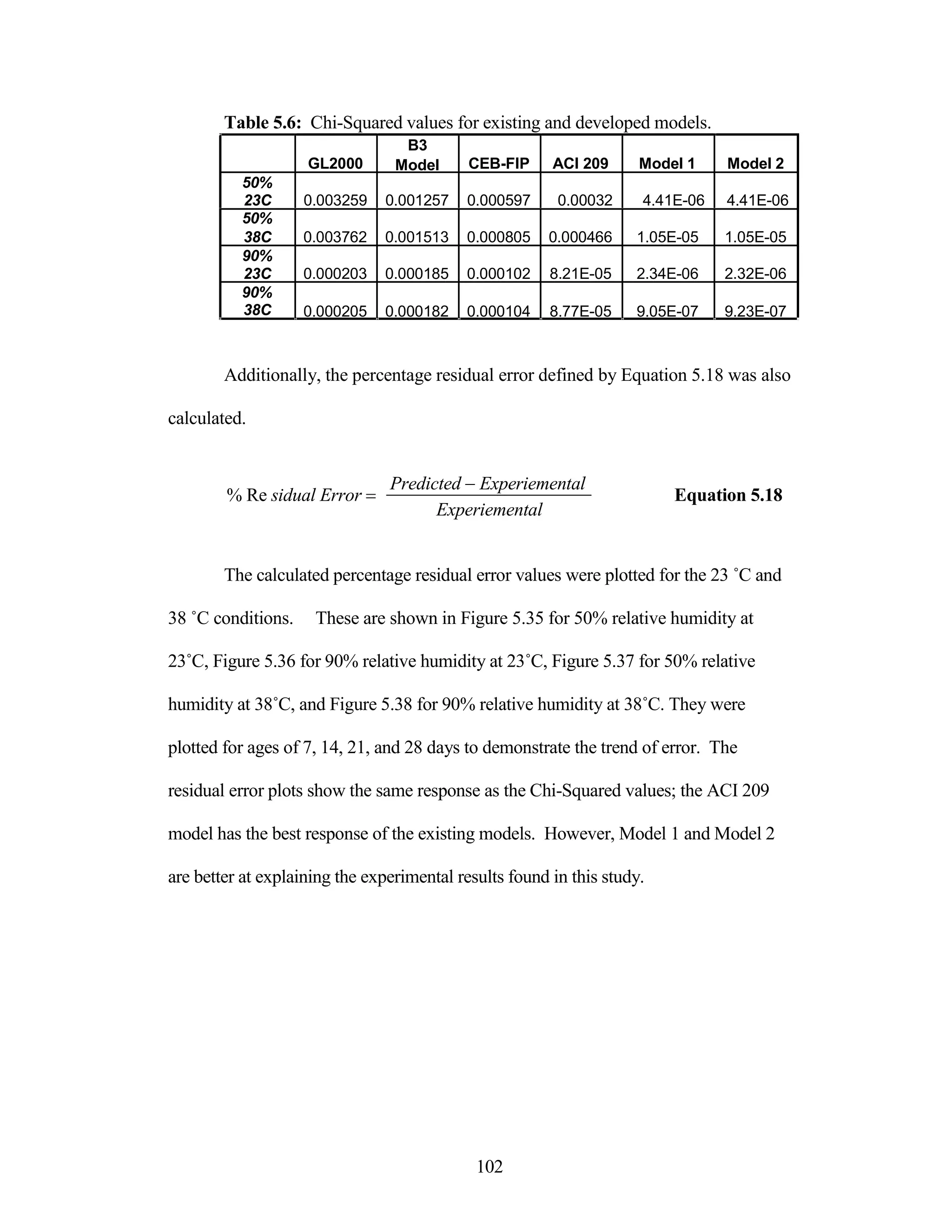

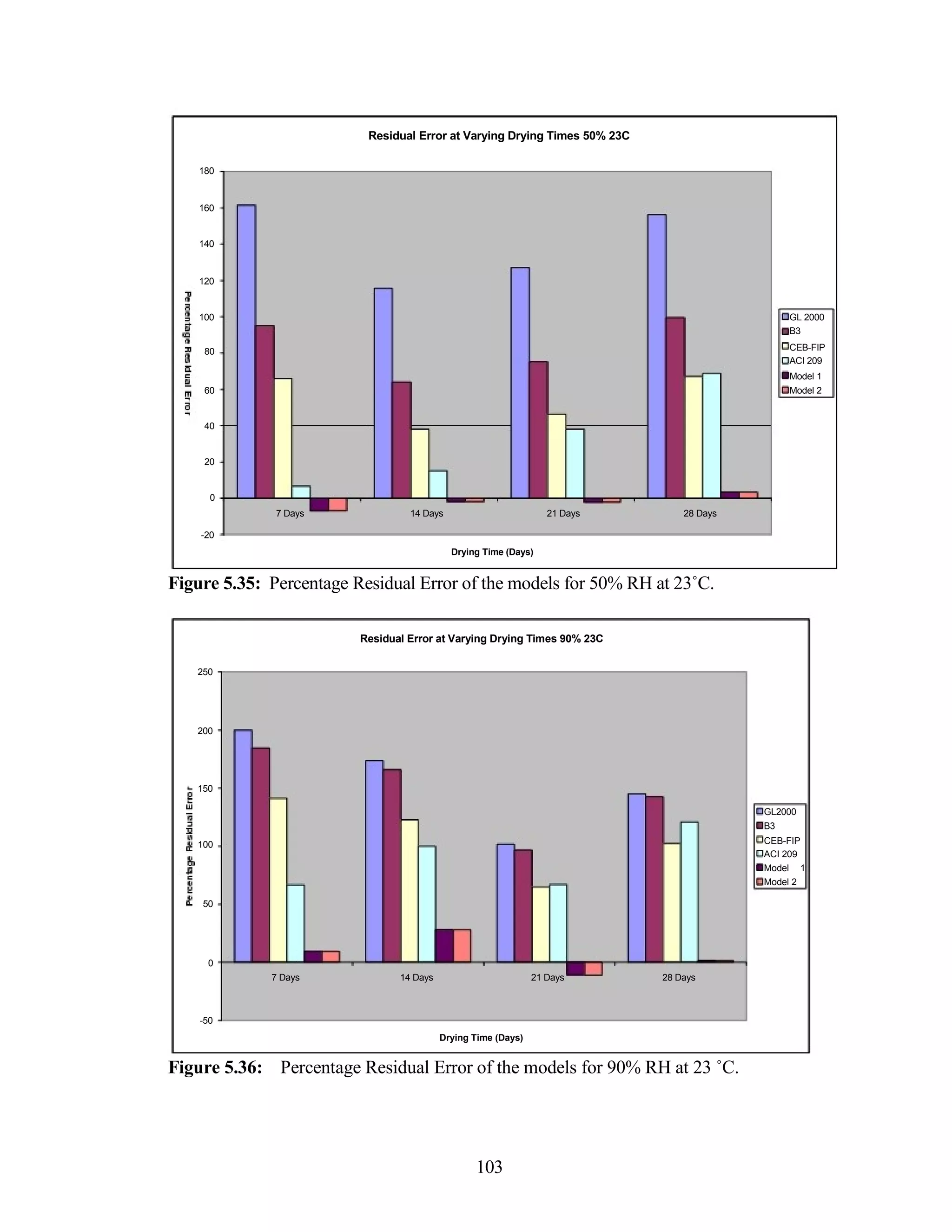

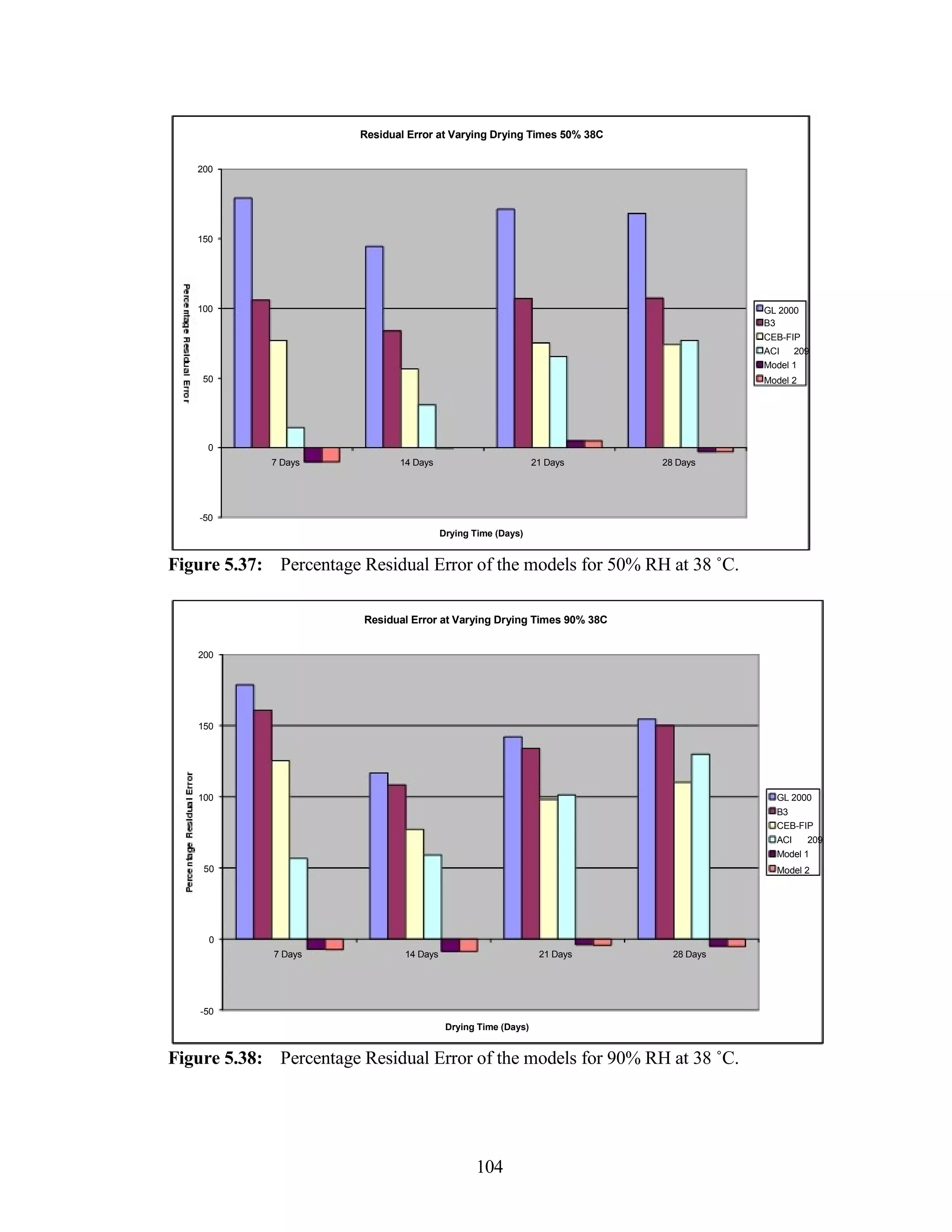

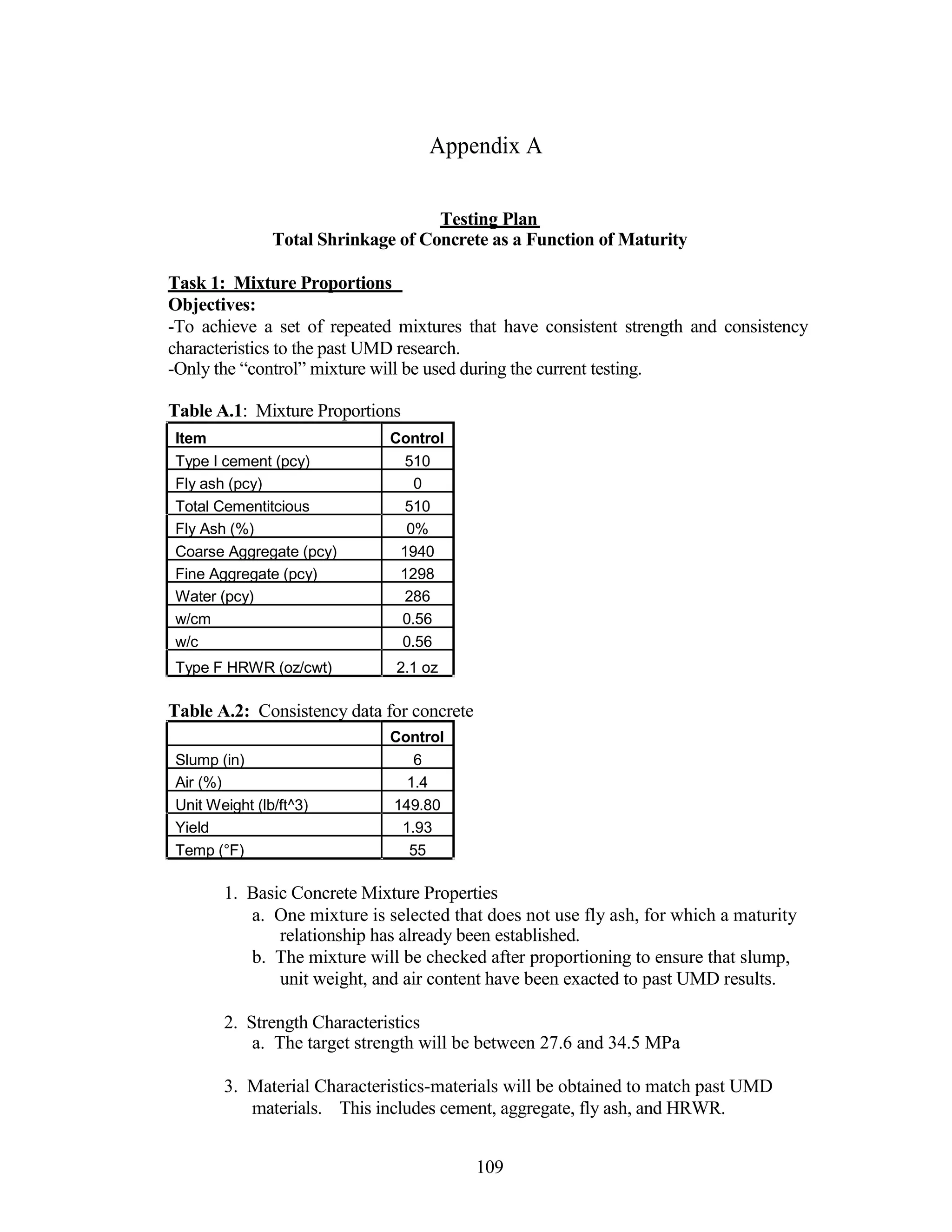

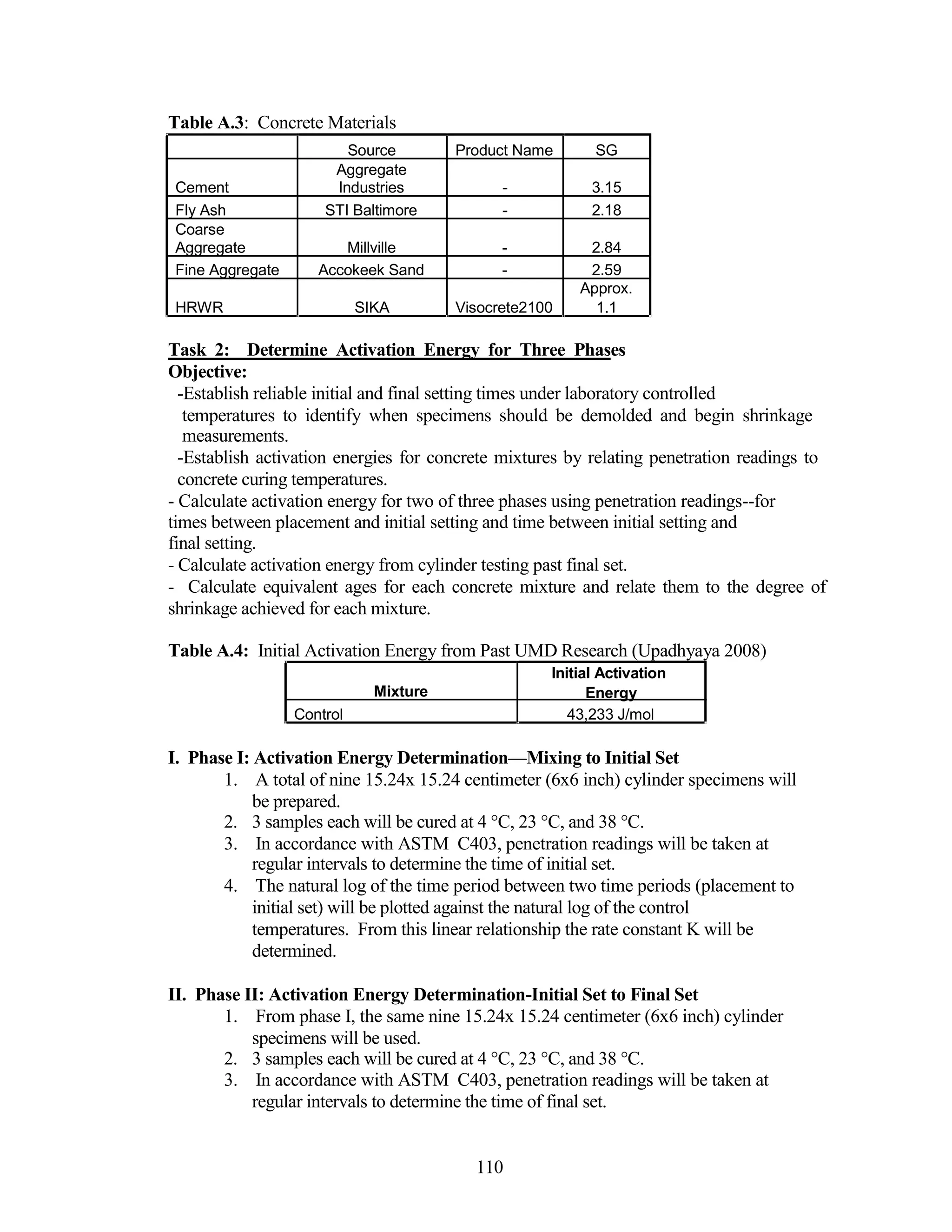

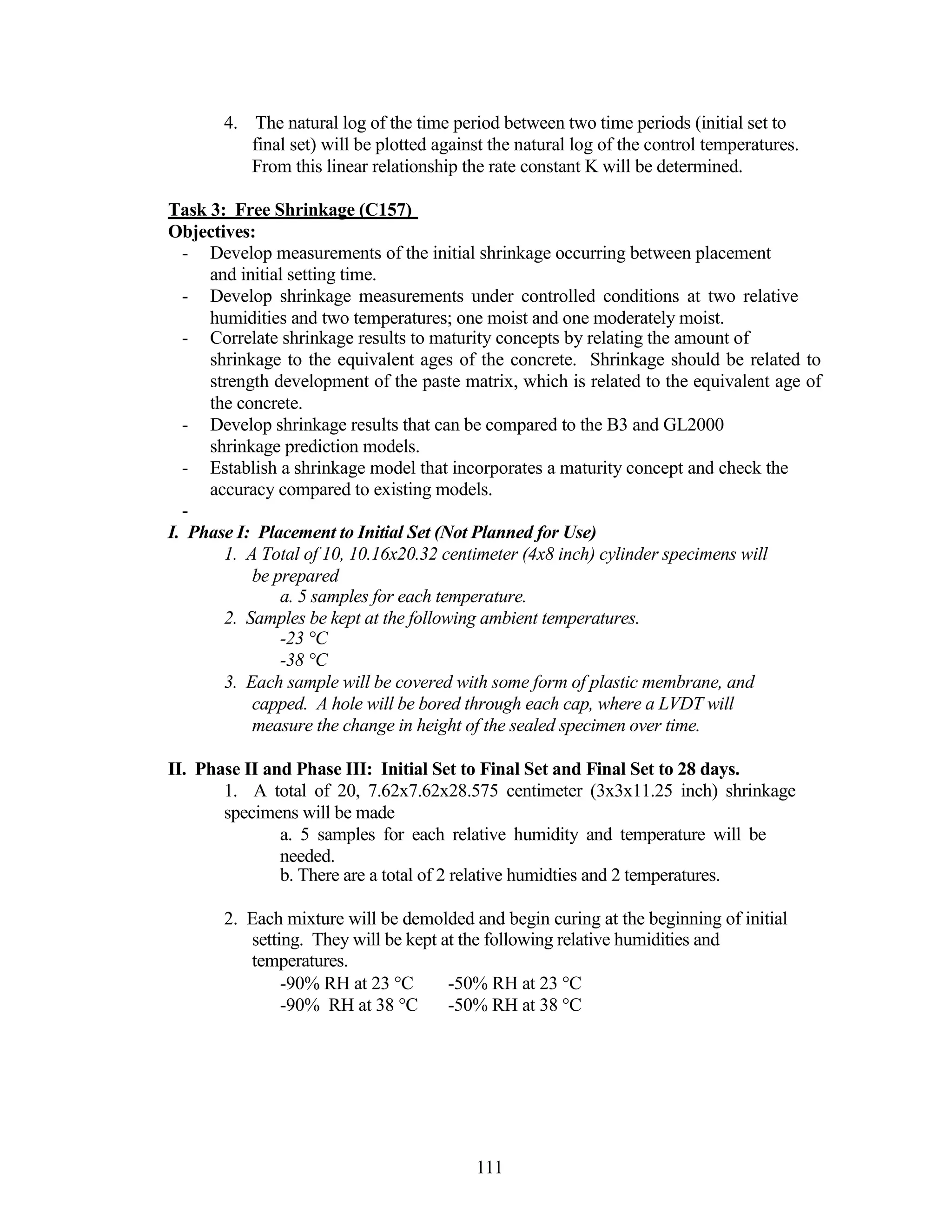

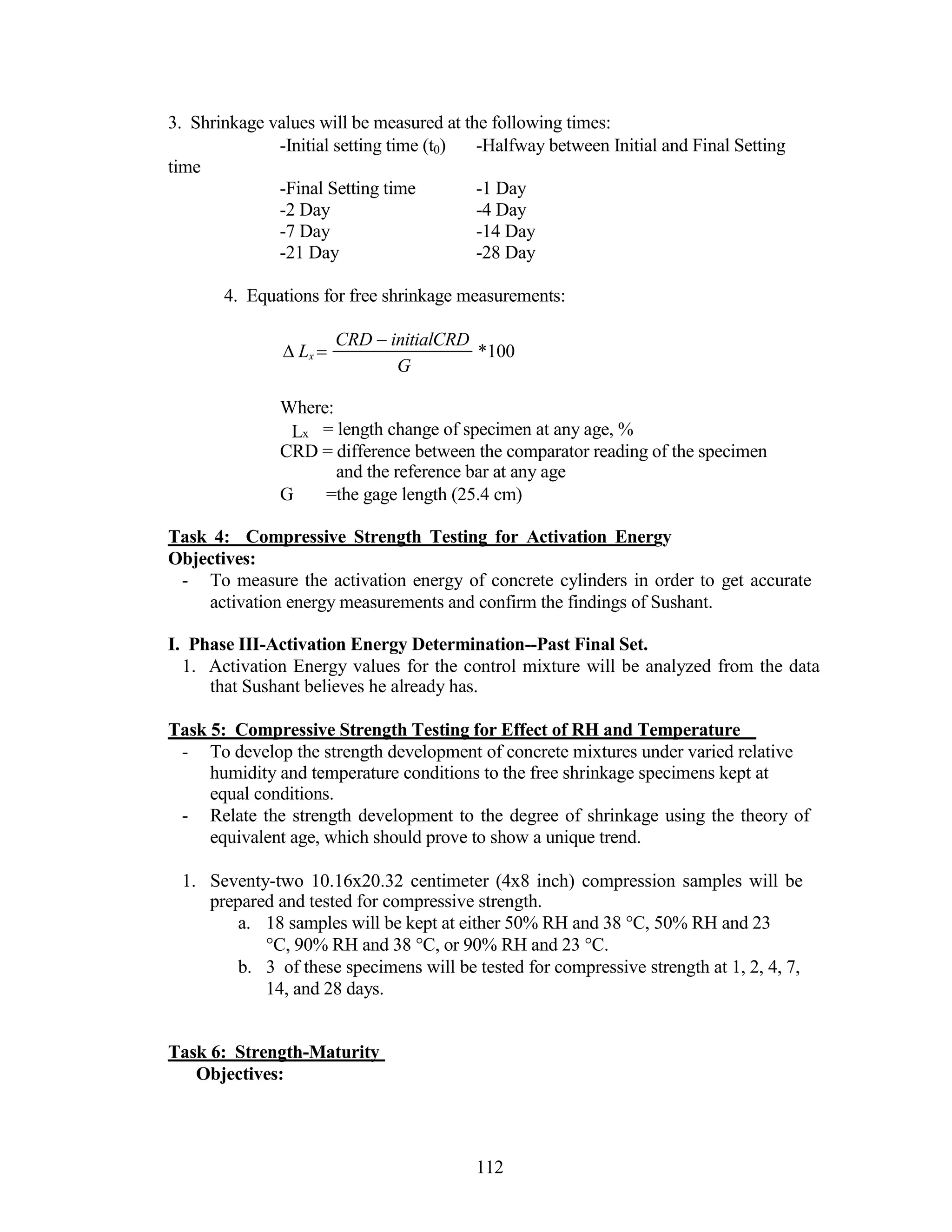

The document discusses a study conducted by Cadmantra Technologies Pvt. Ltd. on predicting concrete shrinkage using maturity and activation energy. It investigates the correlation between concrete's activation energy-based maturity and its shrinkage under various environmental conditions, developing a model to predict shrinkage based on temperature and humidity. The study includes experimental results, a literature review, and a comparison of existing shrinkage prediction models.