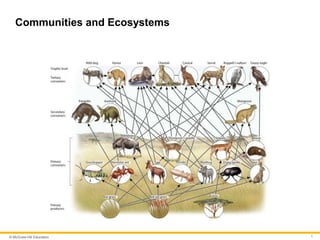

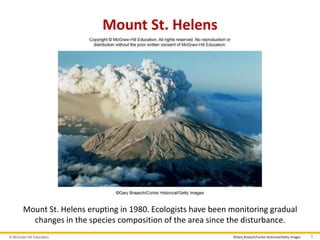

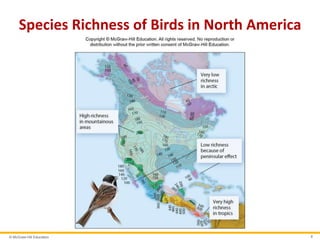

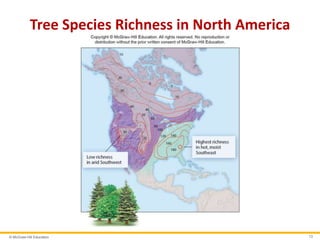

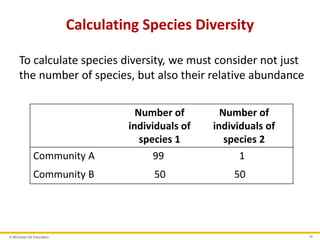

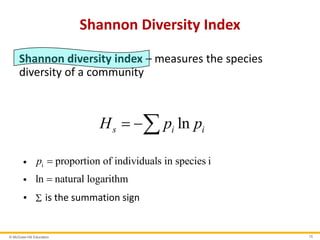

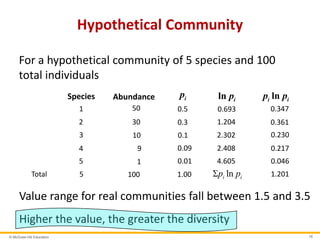

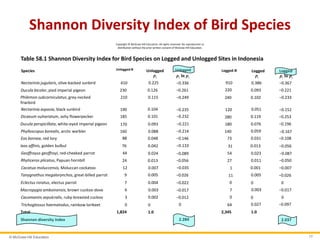

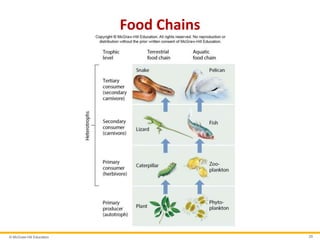

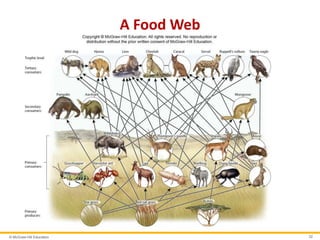

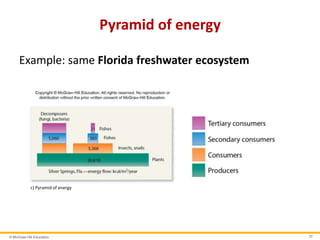

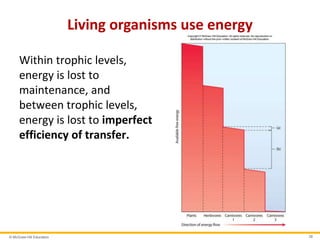

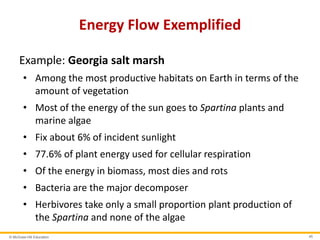

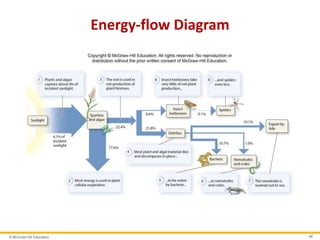

This document provides an overview of key concepts in community and ecosystem ecology. It begins by defining communities and ecosystems, and explaining the differences between community ecology and ecosystem ecology. It then covers various measures of diversity in biological communities, including species richness, species diversity indices, and factors that influence global patterns of species richness. Succession and nutrient cycling in ecosystems are also discussed. The roles of producers, consumers, and decomposers across trophic levels are defined. [END SUMMARY]