The document outlines the Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) framework, detailing various maturity levels, core process areas, and specific practices associated with each level. It explores the policies and organizational expectations necessary to institutionalize managed processes, along with the resources required for effective implementation. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of planning, monitoring, and evaluating processes to achieve quality and performance objectives.

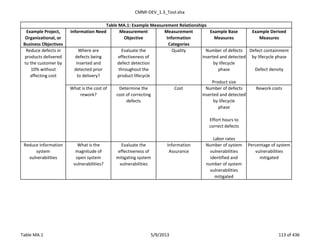

![CMMI-DEV_1.3_Tool.xlsx

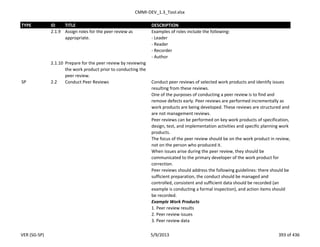

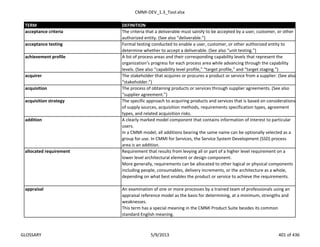

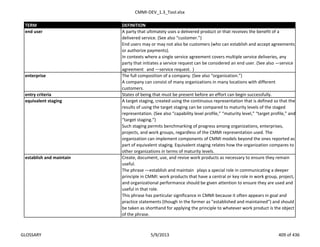

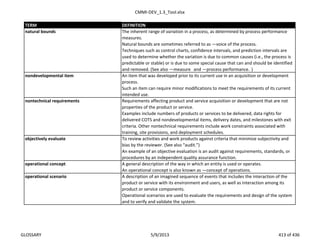

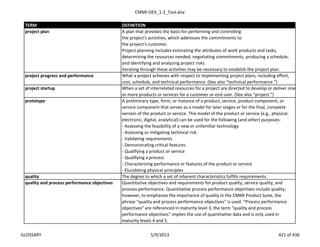

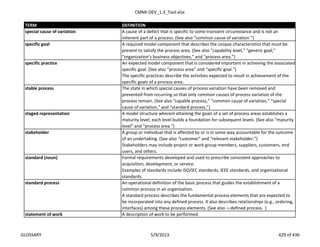

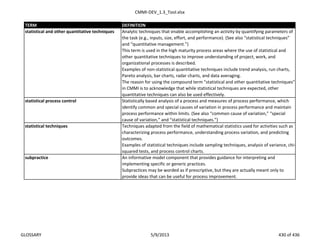

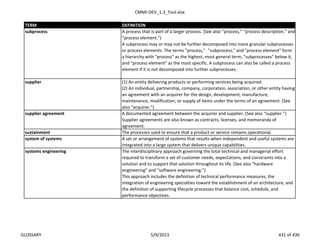

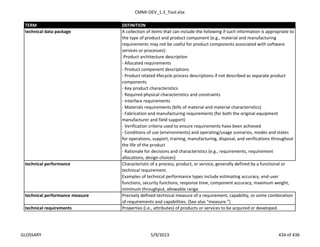

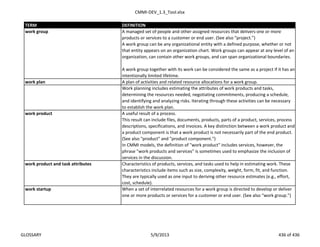

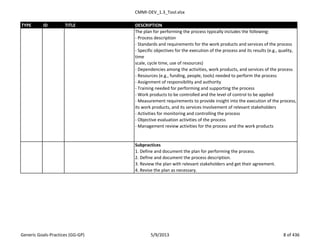

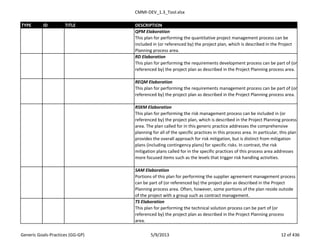

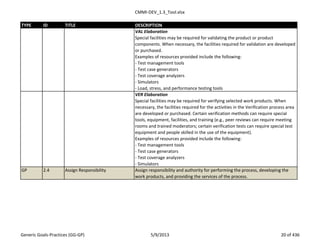

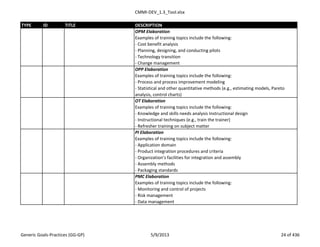

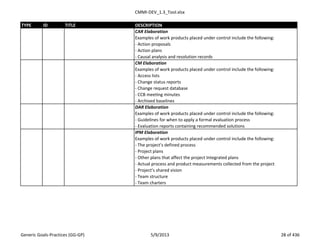

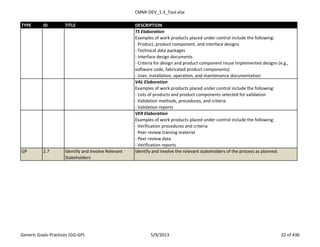

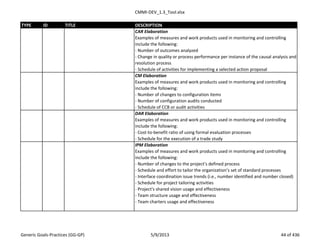

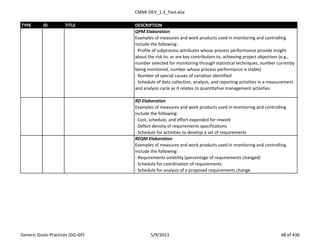

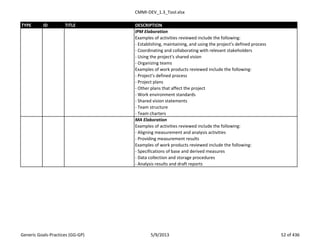

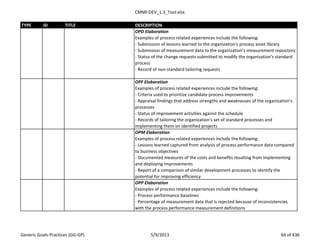

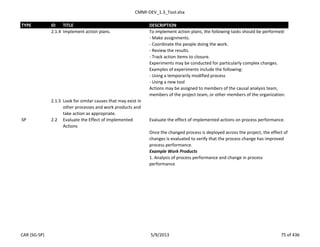

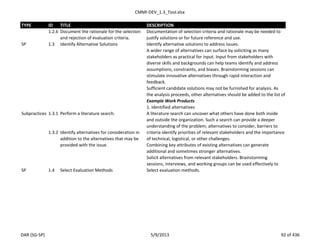

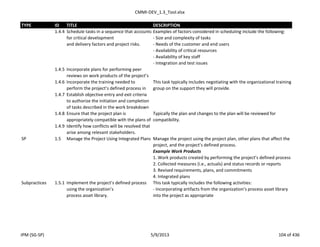

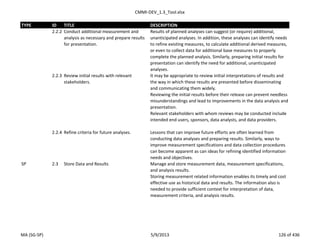

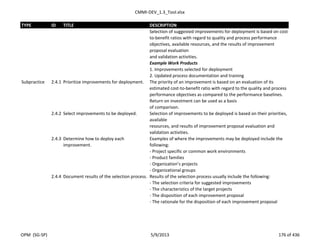

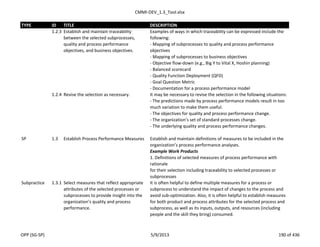

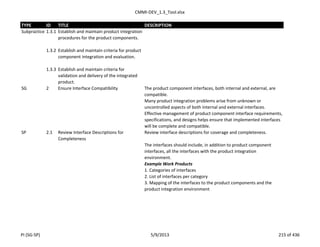

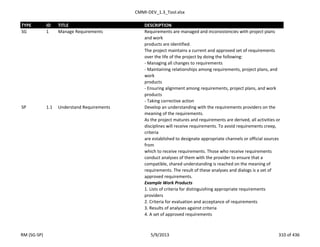

TYPE ID TITLE DESCRIPTION

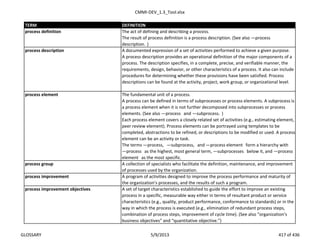

Subpractice 1.1 Identify policies, standards, and business

objectives that are applicable to the

organization’s processes.

Examples of standards include the following:

- ISO/IEC 12207:2008 Systems and Software Engineering – Software

Life Cycle

Processes [ISO 2008a]

- ISO/IEC 15288:2008 Systems and Software Engineering – System Life

Cycle

Processes [ISO 2008b]

- ISO/IEC 27001:2005 Information technology – Security techniques –

Information Security Management Systems – Requirements [ISO/IEC

2005]

- ISO/IEC 14764:2006 Software Engineering – Software Life Cycle

Processes – Maintenance [ISO 2006b]

- ISO/IEC 20000 Information Technology – Service Management [ISO

2005b]

- Assurance Focus for CMMI [DHS 2009]

- NDIA Engineering for System Assurance Guidebook [NDIA 2008]

- Resiliency Management Model [SEI 2010c]

1.1.2 Examine relevant process standards and

models for best practices.

1.1.3 Determine the organization’s process

performance objectives.

Process performance objectives can be expressed in quantitative or

qualitative terms.

Refer to the Measurement and Analysis process area for more

information about establishing measurement objectives.

Refer to the Organizational Process Performance process area for

more information about establishing quality and process performance

objectives.

OPF (SG-SP) 5/9/2013 146 of 436](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cmmi-dev1-3tool-130509133406-phpapp01/85/CMMI-DEV-1-3-Tool-checklist-146-320.jpg)

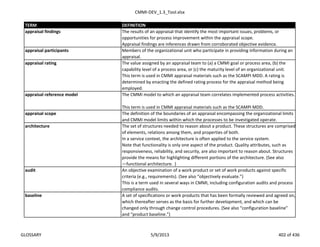

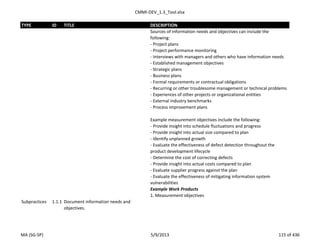

![CMMI-DEV_1.3_Tool.xlsx

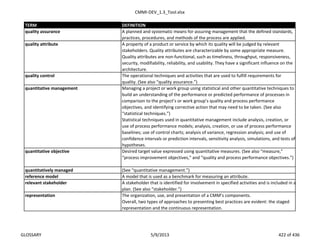

TYPE ID TITLE DESCRIPTION

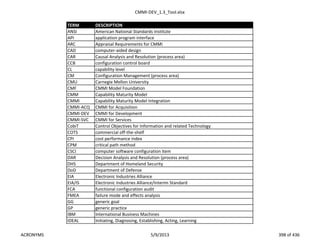

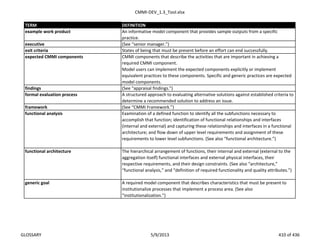

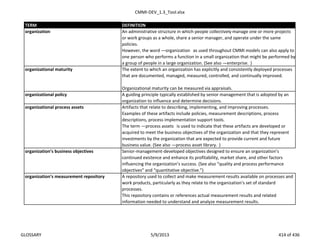

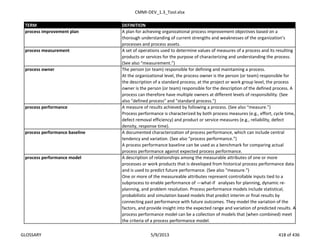

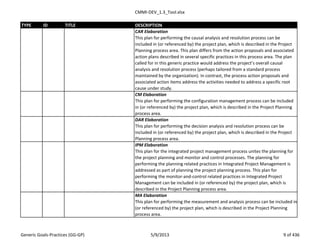

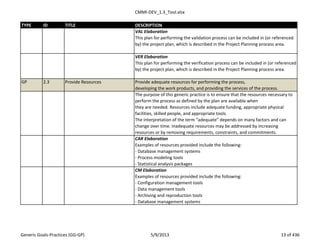

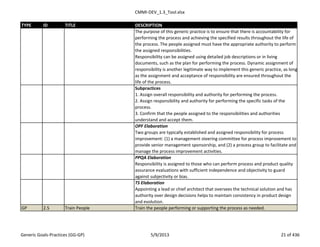

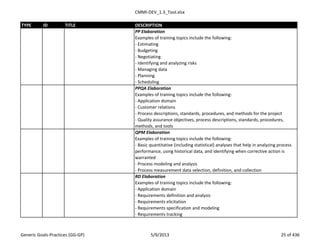

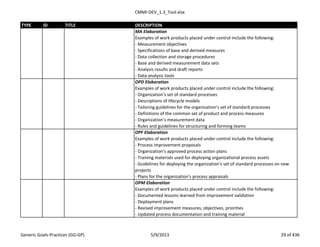

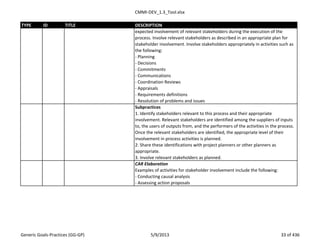

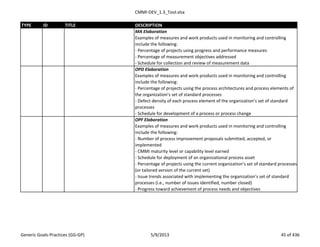

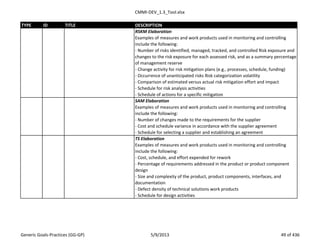

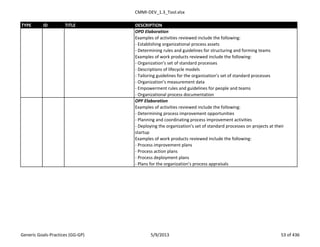

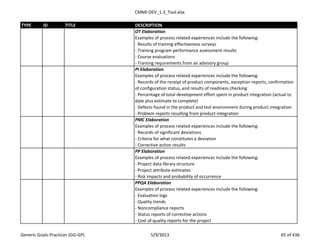

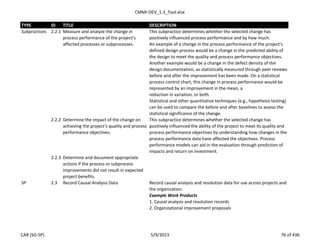

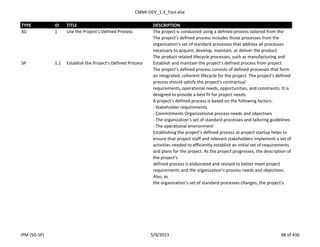

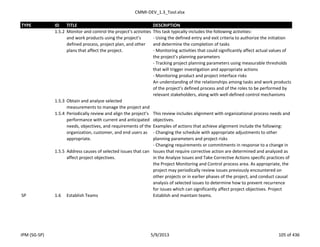

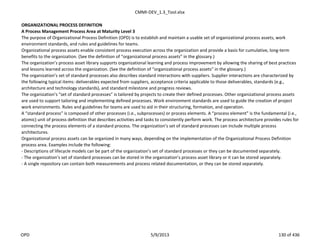

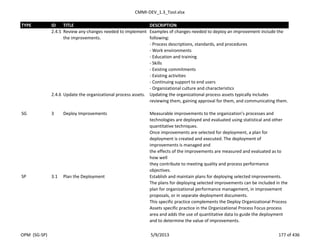

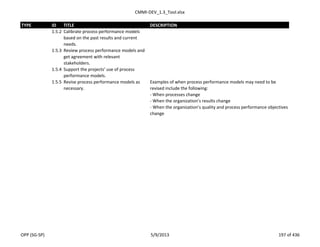

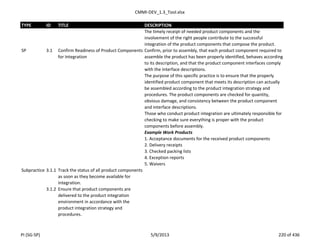

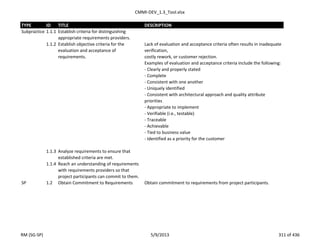

1.2.3 Determine the method and criteria to be

used for the process

appraisal.

Process appraisals can occur in many forms. They should address the

needs and objectives of the organization, which can change over time.

For example, the appraisal

can be based on a process model, such as a CMMI model, or on a

national or

international standard, such as ISO 9001 [ISO 2008c]. Appraisals can

also be based

on a benchmark comparison with other organizations in which

practices that can

contribute to improved organizational performance are identified. The

characteristics of

the appraisal method may vary, including time and effort, makeup of

the appraisal

team, and the method and depth of investigation.

1.2.4 Plan, schedule, and prepare for the process

appraisal.

1.2.5 Conduct the process appraisal.

1.2.6 Document and deliver the appraisal’s

activities and findings.

SP 1.3 Identify the Organization’s Process

Improvements

Identify improvements to the organization’s processes and

process assets.

Example Work Products

1. Analysis of candidate process improvements

2. Identification of improvements for the organization’s processes

OPF (SG-SP) 5/9/2013 149 of 436](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cmmi-dev1-3tool-130509133406-phpapp01/85/CMMI-DEV-1-3-Tool-checklist-149-320.jpg)

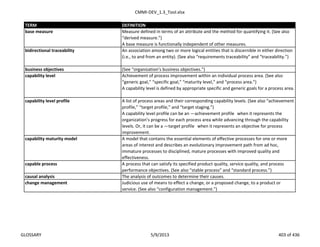

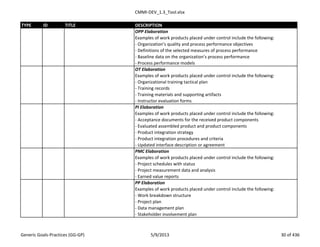

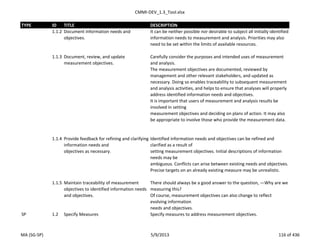

![CMMI-DEV_1.3_Tool.xlsx

TYPE ID TITLE DESCRIPTION

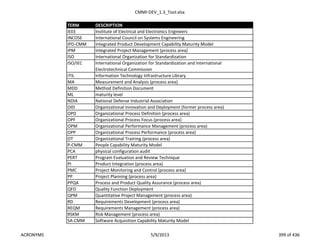

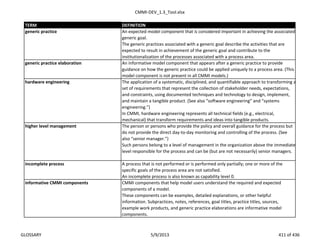

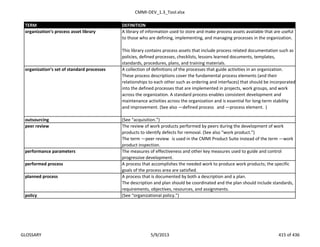

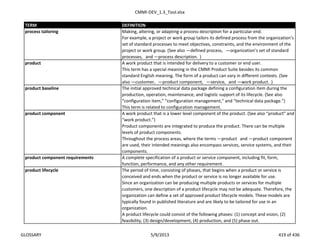

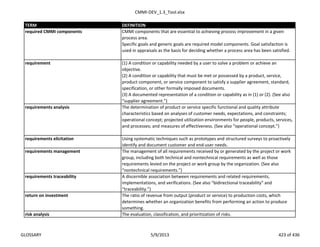

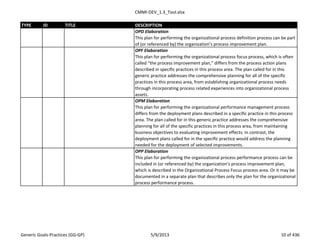

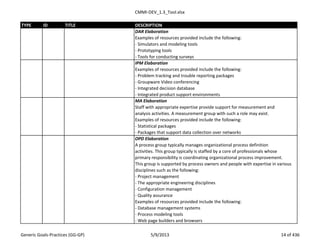

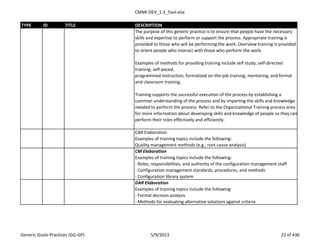

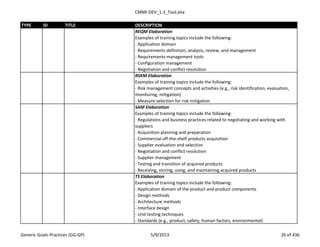

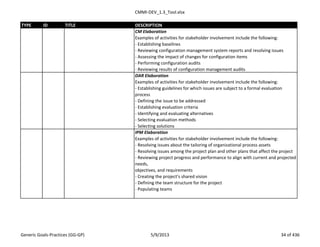

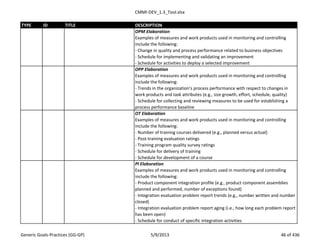

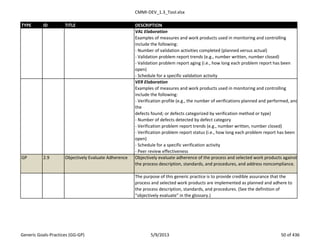

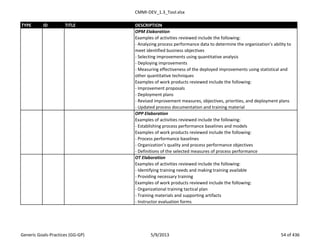

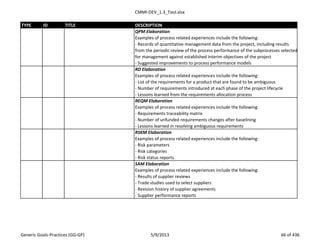

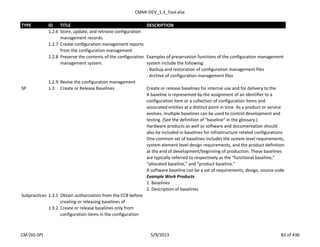

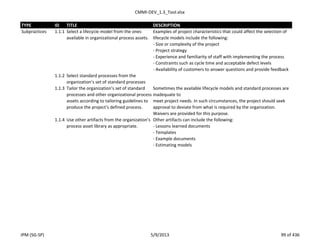

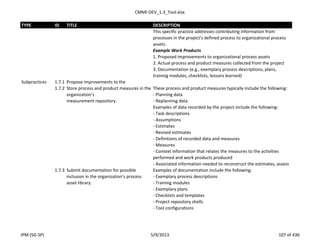

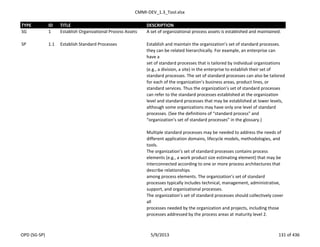

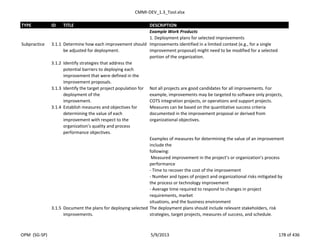

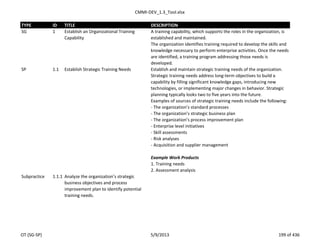

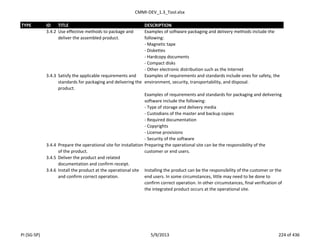

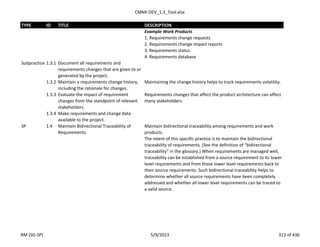

Examples of interfaces (e.g., for mechanical or electronic components)

that can be classified within these three classes include the following:

- Mechanical interfaces (e.g., weight and size, center of gravity,

clearance of parts in operation, space required for maintenance, fixed

links, mobile links, shocks and vibrations received from the bearing

structure)

- Noise interfaces (e.g., noise transmitted by the structure, noise

transmitted in the air, acoustics)

- Climatic interfaces (e.g., temperature, humidity, pressure, salinity)

- Thermal interfaces (e.g., heat dissipation, transmission of heat to the

bearing structure, air conditioning characteristics)

- Fluid interfaces (e.g., fresh water inlet/outlet, seawater inlet/outlet

for a naval/coastal product, air conditioning, compressed air, nitrogen,

fuel, lubricating oil, exhaust gas outlet)

- Electrical interfaces (e.g., power supply consumption by network

with transients and peak values; nonsensitive control signal for power

supply and communications; sensitive signal [e.g., analog links];

disturbing signal [e.g., microwave]; grounding signal to comply with

the TEMPEST standard)

- Electromagnetic interfaces (e.g., magnetic field, radio and radar

links, optical band link wave guides, coaxial and optical fibers)

- Human-machine interface (e.g., audio or voice synthesis, audio or

voice recognition, display [analog dial, liquid crystal display, indicators'

light emitting diodes], manual controls [pedal, joystick, track ball,

keyboard, push buttons, touch screen])

- Message interfaces (e.g., origination, destination, stimulus,

2.1.2 Ensure that product components and

interfaces are marked to ensure

easy and correct connection to the joining

product component.

PI (SG-SP) 5/9/2013 217 of 436](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cmmi-dev1-3tool-130509133406-phpapp01/85/CMMI-DEV-1-3-Tool-checklist-217-320.jpg)

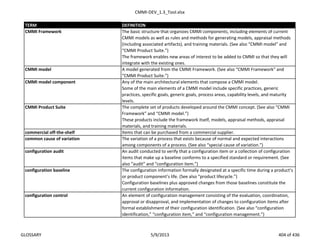

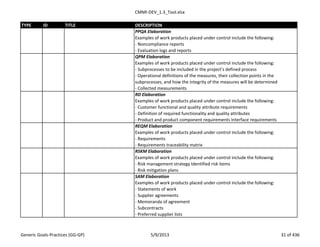

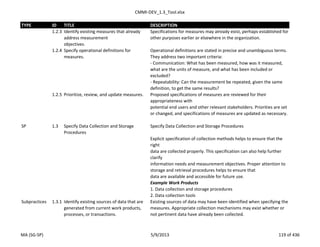

![CMMI-DEV_1.3_Tool.xlsx

TYPE ID TITLE DESCRIPTION

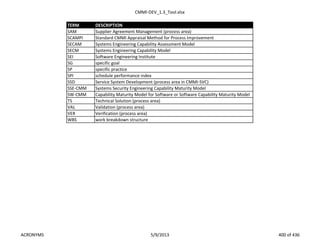

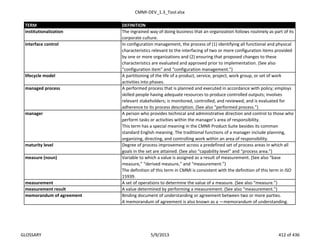

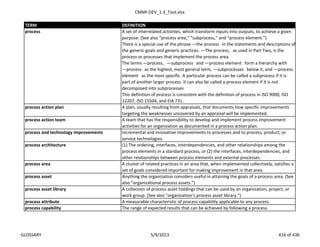

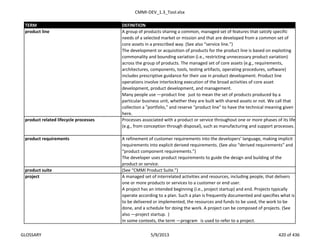

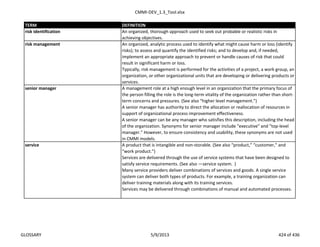

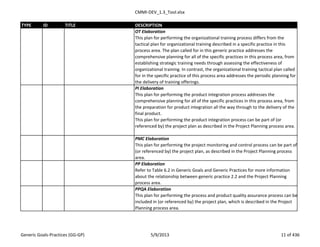

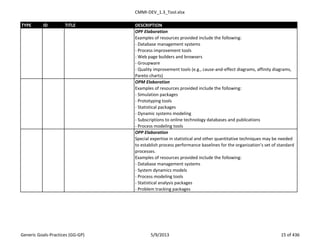

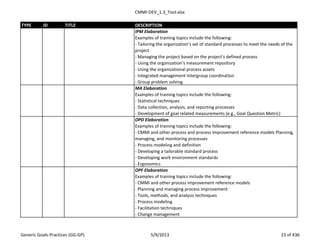

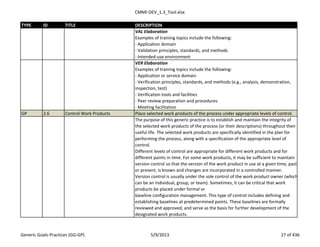

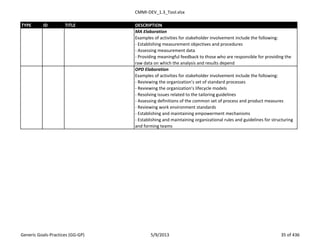

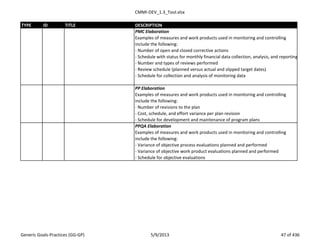

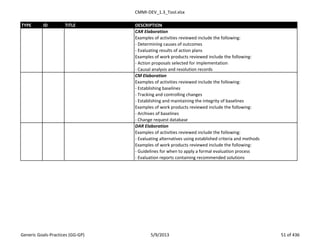

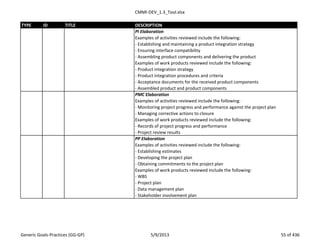

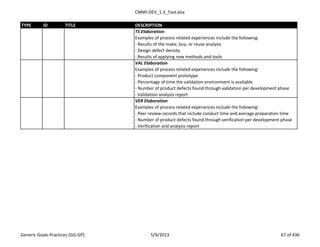

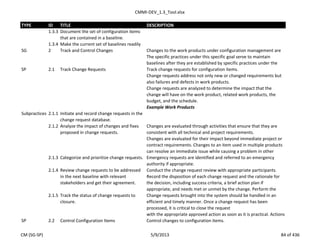

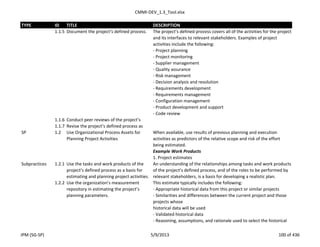

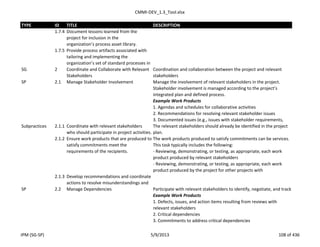

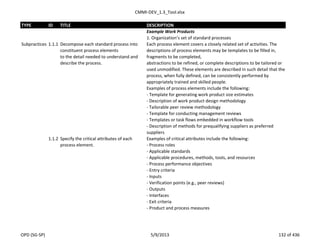

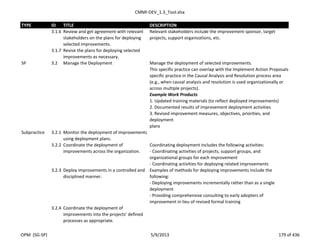

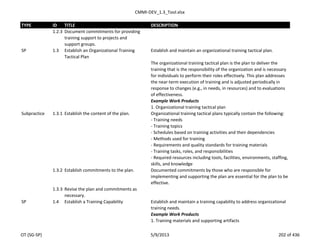

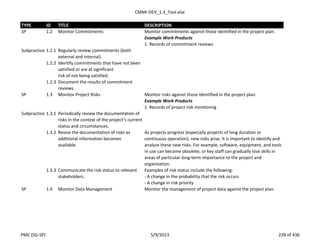

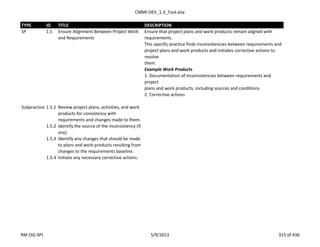

1.4.2 Include supporting infrastructure needs

when estimating effort and cost.

The supporting infrastructure includes resources needed from a

development and sustainment perspective for the product.

Consider the infrastructure resource needs in the development

environment, the test

environment, the production environment, the operational

environment, or any appropriate combination of these environments

when estimating effort and cost.

Examples of infrastructure resources include the following:

- Critical computer resources (e.g., memory, disk and network

capacity, peripherals, communication channels, the capacities of these

resources)

- Engineering environments and tools (e.g., tools for prototyping,

testing, integration, assembly, computer-aided design [CAD],

simulation)

- Facilities, machinery, and equipment (e.g., test benches, recording

devices)

PP (SG-SP) 5/9/2013 241 of 436](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cmmi-dev1-3tool-130509133406-phpapp01/85/CMMI-DEV-1-3-Tool-checklist-241-320.jpg)

![CMMI-DEV_1.3_Tool.xlsx

TYPE ID TITLE DESCRIPTION

Subpractice 1.3.1 Analyze how subprocesses, their

attributes, other factors, and project

performance results relate to each other.

A root cause analysis, sensitivity analysis, or process performance

model can help to identify the subprocesses and attributes that most

contribute to achieving particular

performance results (and variation in performance results) or that are

useful indicators of future achievement of performance results.

1.3.2 Identify criteria to be used in selecting

subprocesses that are key

contributors to achieving the project’s

quality and process performance

objectives.

Examples of criteria used to select subprocesses include the following:

- There is a strong correlation with performance results that are

addressed in the project’s objectives.

- Stable performance of the subprocess is important.

- Poor subprocess performance is associated with major risks to the

project.

- One or more attributes of the subprocess serve as key inputs to

process performance

models used in the project.

- The subprocess will be executed frequently enough to provide

sufficient data for analysis.

1.3.3 Select subprocesses using the identified

criteria.

Historical data, process performance models, and process

performance baselines can help in evaluating candidate subprocesses

against selection criteria.

1.3.4 Identify product and process attributes to

be monitored.

These attributes may have been identified as part of performing the

previous subpractices. Attributes that provide insight into current or

future subprocess performance are candidates for monitoring,

whether or not the associated subprocesses are under the control of

the project. Also, some of these same attributes may serve other

roles, (e.g., to help in monitoring project progress and performance as

described in Project Monitoring and Control [PMC]).

QPM (SG-SP) 5/9/2013 275 of 436](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cmmi-dev1-3tool-130509133406-phpapp01/85/CMMI-DEV-1-3-Tool-checklist-275-320.jpg)

![CMMI-DEV_1.3_Tool.xlsx

TYPE ID TITLE DESCRIPTION

Because design descriptions can involve a large amount of data and

can be crucial to successful product component development, it is

advisable to establish criteria for organizing the data and for selecting

the data content. It is particularly useful to use the product

architecture as a means of organizing this data and abstracting views

that are clear and relevant to an issue or feature of interest. These

views include the following:

- Customers

- Requirements

- The environment

- Functional

- Logical

- Security

- Data

- States/modes

- Construction

- Management

These views are documented in the technical data package.

Example Work Products

1. Technical data package

Subpractice 2.2.1 Determine the number of levels of design

and the appropriate level of

documentation for each design level.

Determining the number of levels of product components (e.g.,

subsystem, hardware configuration item, circuit board, computer

software configuration item [CSCI], computer software product

component, computer software unit) that require documentation and

requirements traceability is important to manage documentation

costs and to support integration and verification plans.

2.2.2 Determine the views to be used to

document the architecture.

Views are selected to document the structures inherent in the

product and to address particular stakeholder concerns.

TS (SG-SP) 5/9/2013 364 of 436](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cmmi-dev1-3tool-130509133406-phpapp01/85/CMMI-DEV-1-3-Tool-checklist-364-320.jpg)