The document discusses clinical engineering principles and medical equipment planning. It begins with an introduction to healthcare delivery systems and key stakeholders. Clinical engineering is defined as the specialty within biomedical engineering focused on technical services and support related to medical equipment in hospitals. The scope of clinical engineering work includes medical equipment planning during hospital design and equipment operation activities like testing, calibration and maintenance. The document then covers hospital departments and how they are typically grouped, as well as the organizational structure and lifecycle of hospitals. Medical equipment planning is part of the role of clinical engineers in the design and construction of new healthcare facilities.

![16

Review Questions

[1] An interstitial floor is one which is sandwiched between two floors with about half the

regular height. It is used to accommodate all sorts of infrastructure components such as

ventilation pipes.

(a) Which hospital department benefits the most from interstitial floors?

(b) What other services can be provided by the interstitial floor?

(c) Would you consider an interstitial floor as a micro or macro level adaptability?

Why?

(d) Show where in this drawing would interstitial space exist.

(e) Give an example of the kind of hardware you may find in the interstitial space.

(f) From the engineering drawing point of view, give an appropriate name for

this section.

(g) From the medical planning point of view, give an appropriate name for this

kind of drawing.

(h) Suggest names for the other (non-interstitial) spaces by writing them on the

figure. Explain your choices. [4 points]

(i) Make a room-by-room list for the non-interstitial spaces. Make any

REASONABLE assumptions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/clinicalengineeringprinciples-2018-200816181850/85/Clinical-engineering-principles-2018-16-320.jpg)

![21

Definitions:

[Source: http://edissues.wikidot.com/estimating-

departmental-gross-square-footage ]

Net Square Feet (NSF): The space within the walls of a

room or the usable floor area assigned to a function in

an open area, e.g., cubicles or workstations. The space

includes casework, fixtures and door swings but does

not include wall thicknesses.

Departmental Gross Square Feet (DGSF): the space

inside the centerline of the walls separating a

department from adjoining areas; includes internal

walls, corridors, etc.

Building Gross Square Feet (BGSF): It is the total area of

the facility including outside walls, mechanical spaces

and canopies.

Net to Gross Factor or Grossing Factor: It is a multiplication factor applied to space to increase the

allotment to accommodate elements not in the base number. A grossing factor is applied to space

lists on Net Square feet to take into account internal circulation and walls to give Departmental

Gross Square Feet (DGSF). Another factor is used to increase DGSF to Building Gross Square Feet

(BGSF) and estimate the amount required for major vertical circulation, shafts and building

circulation. As a rule of thumb, building gross is approximately twice the amount of net area in a

hospital.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/clinicalengineeringprinciples-2018-200816181850/85/Clinical-engineering-principles-2018-21-320.jpg)

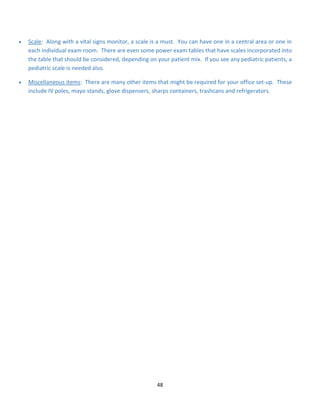

![43

Calculating the MDI score

The scoring matrices shown in Tables 1 and 2 are used in conjunction with the MDI algorithm to calculate the MDI

score. Using a matrix to quantify and prioritize risk severity does not eliminate the inherently subjective nature of

risk assessment; however, a matrix does provide a consistent framework for evaluating risk.

The MDI is calculated using an equation with three coefficients. The MD(Within) and MD(Between) scores are a

resultant of the matrices used in the intra and inter- dependency lines of question. The third input is the number

(n) of other subcomponents recognizing the subject subcomponent as a mission critical service provider. The

following MDI equation and weighted coefficients are the result of three years of extensive field-testing by Navy,

Coast Guard and NASA facility engineers and managers:

MDI = [MD(Within) + *MD(Between Average) + Ln(n)] –

Where:

• MDI = Mission Dependency Index normalized from zero to 100

• MD(Within) = Intra-dependency Score; response to questions 1 and 2 (see Table 1)

• MD(Between) = (Interdependency Score): The average response to questions 3 and 4, (see Table 2)

• Ln( ) = natural log function

• n = number of Interdependencies with other Functional Areas

The natural log function is used because the difference between 1 and 2 is much more relevant than the difference

between 11 and 12.

The MDI color code and nomenclature used is as follows:

Scoring is divided into five categories with a 15 point spread separating critical, significant, relevant, moderate,

and low. The MDI equation is weighted to allow functional elements with high inter-dependency scores to move

up to the next level of criticality. The exception is functional elements with very low intra-dependency scores (less

than 25).

The MDI has been recognized by the US General Services Administration in 2003 as a “Best Practice” and by the

Federal Facilities Council (Cable and Davis 2005) as “a promising process indicator for prioritizing projects and

funding to support an organization’s overall mission”. When combined with other metrics, such as a Condition

Index (CI), MDI can be used to prioritize funding for projects having the most positive impact. MDI is valuable for

prioritizing real property resources in the conduct of facility assessments. In this area, facilities with high MDI](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/clinicalengineeringprinciples-2018-200816181850/85/Clinical-engineering-principles-2018-43-320.jpg)

![46

Chapter Questions

[1] Design a minor operating room and its related services following the steps discussed in this

chapter.

Hint

In the concept design phase, we should describe the design requirements in a general but definite way.

First, we must define what is meant by minor surgery. A minor surgery is a surgical procedure that does

not require general anesthetic such as:

Main Category Operations

Injections intra-articular, peri-articular, varicose veins, haemorrhoids

Aspirations joints, cysts, bursae, hydrocele

Incisions abscesses, cysts, thrombosed piles

Excisions sebaceous cysts, lipoma, warts, skin lesions for histology, intradermal naevi,

papilloma,

dermatofibroma and similar lesions, removal of toenails

Curette, cautery and

cryo-cautery

warts and verrucae, other skin lesions (skin surgery) (e.g. molluscum

contagiosum)

Other removal of foreign bodies, nasal cautery

Second, these procedures should be mapped into services and medical equipment.

[2] Make a room-by-room list of a typical Examination Room in the Outpatient Clinic

Answer

Exam Table: An adjustable exam table, ideally with cabinets and storage beneath, is an absolute “must

have” and will provide a place to examine patients while also providing much needed storage without

taking up extra floor space. There are many new laws in the works that address the ADA (Americans

with Disabilities Act). A power exam table that goes as low as 18” should be considered. Not only will it

be ADA friendly, but could increase the workflow of an office, allowing more patients to be seen in a day.

Integrated Diagnostic System: An integrated diagnostic system provides you everything you will require

for a basic examination. You will be able to perform checks using an ophthalmoscope, otoscope,

sphygmomanometer, and an electronic thermometer. Having a wall-mounted diagnostic system will

keep everything you need for the medical exam at arms-reach, as well as keeping everything charged so

you never have to worry about having your equipment fail while you are mid-exam. If wall space is

limited you can also consider a wall-mounted transformer with heads that can be switched up as

required based on the patient’s needs. If you cannot accommodate an integrated system you will](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/clinicalengineeringprinciples-2018-200816181850/85/Clinical-engineering-principles-2018-46-320.jpg)

![50

3.1.1 Overview

Life Cycle Asset Management (LCAM) (also called Enterprise Asset Management, EAM15) is an integrated

approach to optimizing the life cycle of assets beginning with user requirements specifications,

continuing through operation and decommissioning. Thorough planning, analysis and timely execution

allow appropriate data-driven decision-making to occur and enable LCAM to deliver optimum:

• Operating and maintenance strategies

• Organizational structure

• Staffing requirements

• Optimized PM/PdM (Preventive & Predictive Maintenance) procedures

15

Enterprise asset management software is a computer software that handles every aspect of running a modern public works

or asset-intensive organization. Effective enterprise asset management (EAM) software solutions include many powerful

features, such as complete asset life-cycle management, flexible preventive maintenance scheduling, complete warranty

management, integrated mobile wireless handheld options and portal-based software interface. [2] Rapid development and

availability of mobile devices also affected EAM software which now often supports Mobile enterprise asset management.

(WIKI)

The above figure obtained from the website of Steris Corporation (a company specialized in the production of sterilizers)

life cycle representation covers BOTH equipment production in the factory AND equipment acquisition in the hospital. In

this course, we separate the two environments of the factory and the hospital in order for the student to grasp the concept

and know how to apply it to the relevant working environment.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/clinicalengineeringprinciples-2018-200816181850/85/Clinical-engineering-principles-2018-50-320.jpg)

![56

Other related financial terms

1- Fixed Cost (Capital cost)

It is a cost that remains the same and does not depend on the amount of goods and services a company

produces. Examples: purchasing price of equipment, apartment rent, and store rent, etc.

2- Variable Cost

It is a cost that varies as the amount of goods and services a company produces varies. A variable cost

is dependent on a company's production volume. Variable Costs include indirect overhead costs such

as Cell Phone Services, Computer Supplies, Credit Card Processing, Electrical use, Janitorial Supplies,

MRO, Office Products, Payroll Services, Telecom, Uniforms, Utilities, or Waste Disposal etc. (WiKi)

3- Asset

A resource with economic value that an individual, corporation or country owns or controls with the

expectation that it will provide future benefit. In the context of accounting, assets are either current

or fixed (non-current). Current means that the asset will be consumed within one year. Generally, this

includes things like cash, accounts receivable and inventory. Fixed assets are those that are expected

to keep providing benefit for more than one year, such as equipment, buildings and real estate.

4- Net present value (NPV)

PV = FV / (1+r)n

where

PV is Present Value, FV is Future Value, r is the interest rate (as a decimal, so 0.10, not 10%),

and n is the number of years.

[Source: http://www.mathsisfun.com/money/net-present-value.html]

5- Internal rate of return (IIR)

6- Return on investment (ROI)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/clinicalengineeringprinciples-2018-200816181850/85/Clinical-engineering-principles-2018-56-320.jpg)

![61

value in each cell of the matrix is the number of days. For example, the value in cell (1,1) is 3, meaning

that between midnight and 1:00 am no teams were needed for three days.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/clinicalengineeringprinciples-2018-200816181850/85/Clinical-engineering-principles-2018-61-320.jpg)

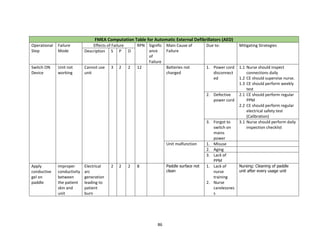

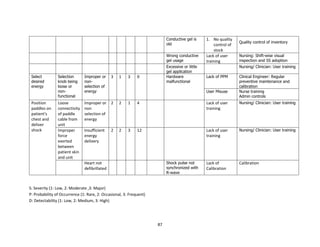

![84

defibrillator is a lifesaving equipment used in emergency situations and any failure/ wrong use

while applying electric shock can lead to first or second degree burns or death of the patient.

The process of using a defibrillator with an external paddle whenever code blue is initiated in a

hospital is shown in the FMEA computation table. The failure mode for each sub process is

tabulated along with effect of each failure, its severity, occurrence and detectability. The possible

cause of failure and mitigating strategies is also filled. The rating for S, O and D are fixed based on

detailed brainstorming session between nursing team, clinicians, head of emergency department

and clinical engineering. The risk priority number for each failure is calculated to understand

which sub process needs priority focus. As we can notice, the following sub process needs

improvements.

1) Switching on defibrillator

2) Positioning of paddles on patient chest and deliver shock

6) Application of conductive gel on paddle

The team assigned the relevant members to work on mitigating strategy. The hospital team, based

on FMEA study, revisited process on maintenance of life saving equipment including defibrillator

and improved on timely preventive maintenance and calibration. The frequency of training and

visual inspection process during daily rounds also increased. The team decided to review the sub

process again after three months, based on the corrective action taken and to revisit the RPN

number. The RPN score for step 1, 2 and 6 came down to 6, 4 and 8 respectively, after

implementing the corrective measures on ground.

The FMEA for defibrillator helped the organisation to strengthen internal processes and to avoid

the potential defect in process, which could have affected patient care. Similar studies can be

done in other areas where medical equipment is involved, as part of the HIRA exercise.

UMDNS Terms

• Defibrillator/Monitors [11-129]

• Defibrillator/Monitors, Line Powered [15-029]

• Defibrillators, Battery Powered [11-134]

• Defibrillators, Line Powered [11-137]

Causes of Device-Related Incident

Device factors:

Improper maintenance, testing, repair, or lack or failure of incoming inspection; Random

component failure](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/clinicalengineeringprinciples-2018-200816181850/85/Clinical-engineering-principles-2018-84-320.jpg)