Here are some examples of FDA-approved therapeutic devices that use direct current (DC) electric fields:

- Bone growth stimulators - Use pulsed electromagnetic fields or capacitively coupled electric fields to promote bone healing of fractures that are not healing on their own.

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulators (TENS) - Apply electric currents to stimulate nerves for pain relief and muscle rehabilitation.

- Iontophoresis devices - Use low-level electrical currents to drive ionized drug molecules through the skin for local drug delivery.

- Cardioversion/defibrillation devices - Apply controlled electric shocks to the heart to treat irregular heart rhythms like atrial fibrillation or ventricular fibrillation.

![32

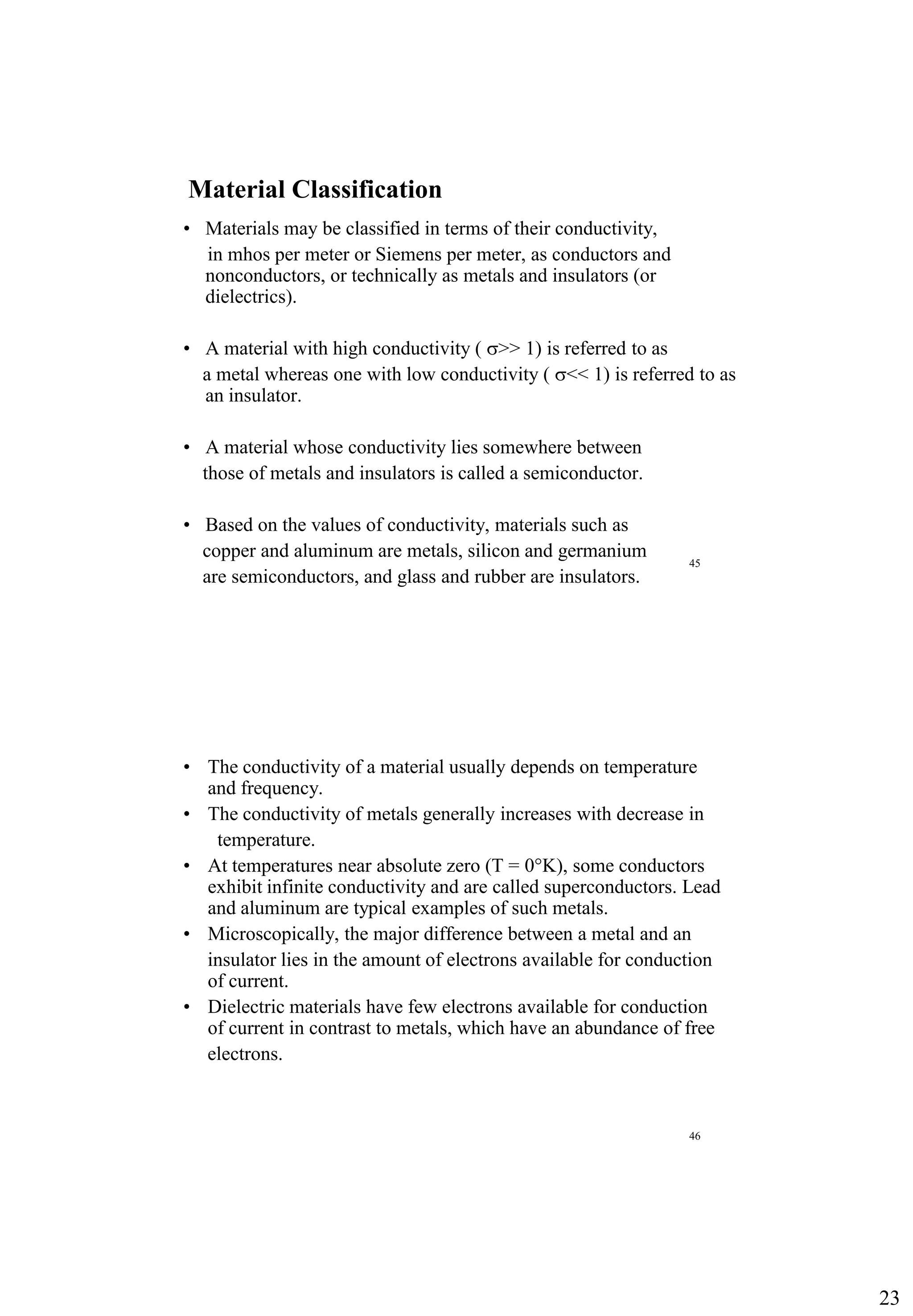

Fura 2-loaded cells showing the elevation of [Ca2+]

i

initiated at rear-end (anode side) and propagating through

entire cell body as a wave (small arrows).(E= 14 V/cm)

63

Promotion of fracture healing

• Electrical current triggers bone growth

• Piezoelectric effect within the collagen matrix

• Alternating current

– Applied transcutaneously

– Similar to diathermy units (no heat production)

• Direct current

– Implanted electrodes

64](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec3-200916091806/75/Fields-Lec-3-32-2048.jpg)