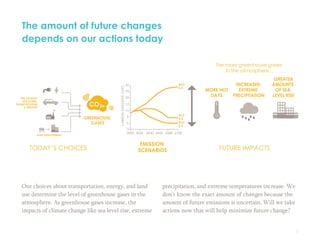

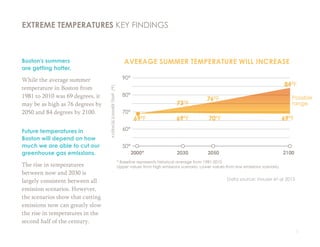

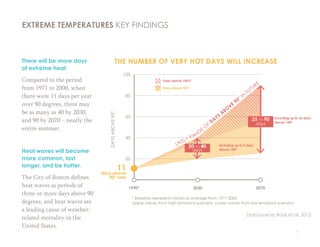

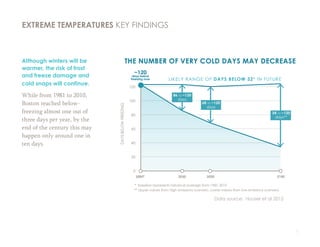

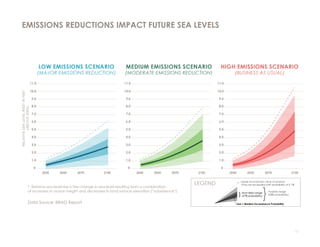

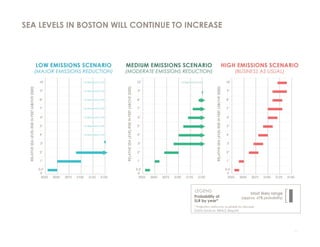

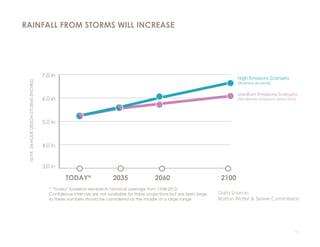

The document summarizes climate projections for Boston from a working group of regional climate scientists. It finds that Boston will see increasing extreme temperatures, heavy precipitation, and sea level rise over the course of the 21st century depending on global greenhouse gas emission levels. Temperatures are projected to rise by over 10 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100 under a high emissions scenario, bringing many more days over 90 degrees each summer. Sea level is projected to rise up to 4 feet by 2070 and over 7 feet by 2100 under a high emissions scenario, increasing coastal flooding and beach erosion. Heavy rainfall events are also expected to continue increasing in frequency and intensity.