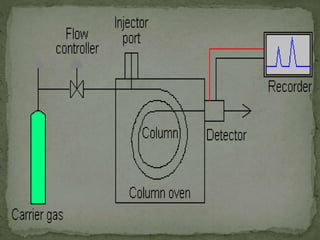

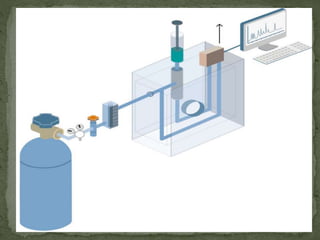

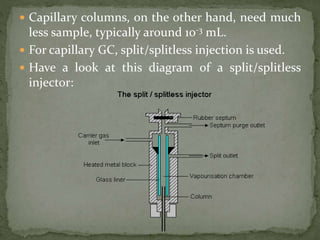

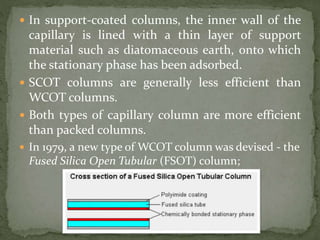

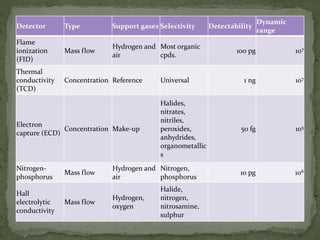

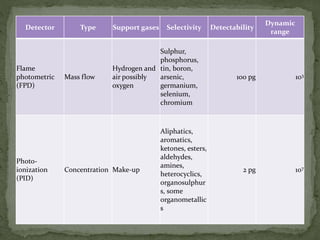

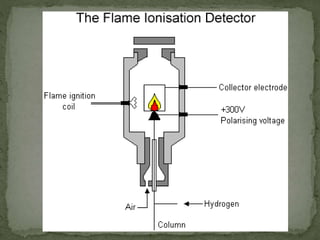

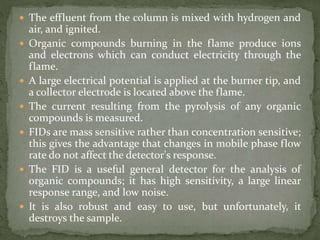

The document provides a detailed overview of chromatography, a laboratory technique for separating mixtures based on different partitioning between a mobile phase and a stationary phase. It describes various types of chromatography, including preparative, analytical, and displacement chromatography, as well as the fundamental principles and applications, particularly in the purification of proteins. Additionally, it discusses gas chromatography, its components, types of columns, and detectors used in the process.