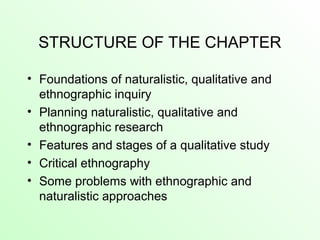

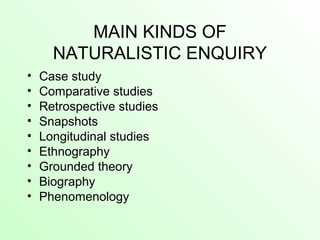

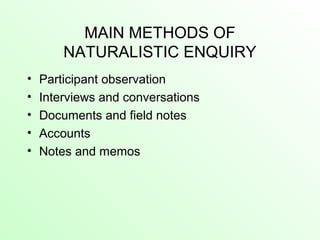

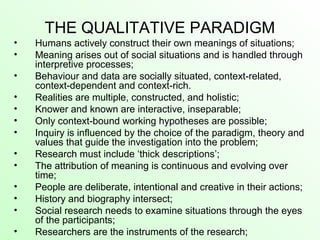

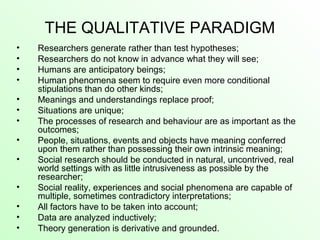

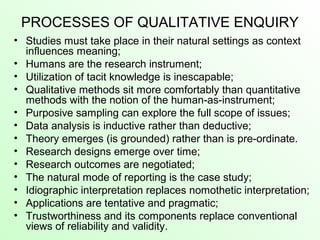

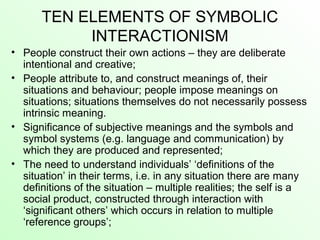

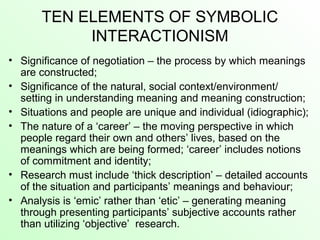

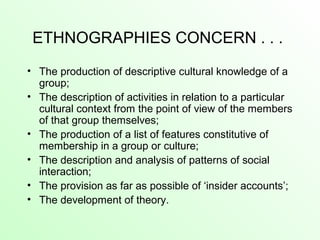

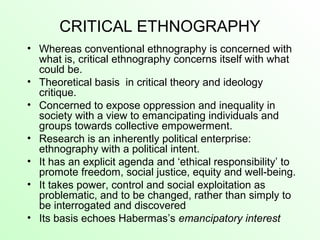

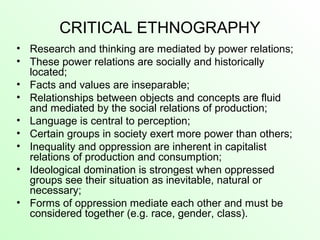

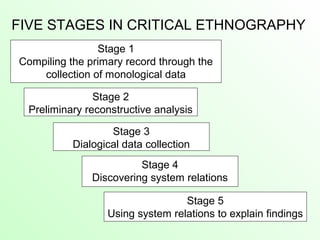

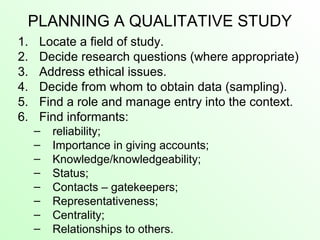

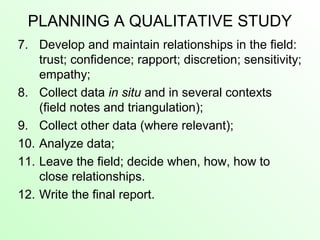

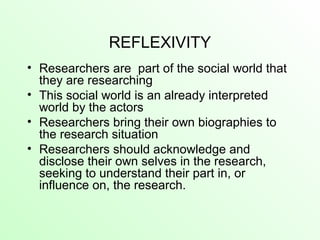

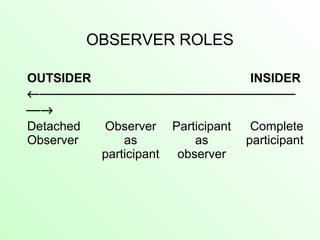

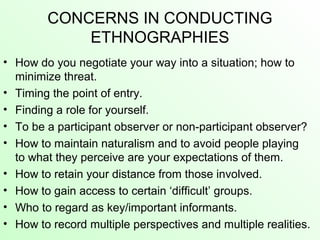

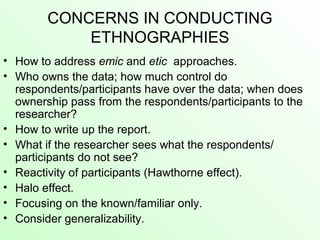

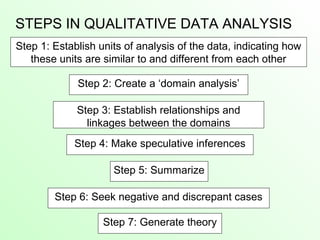

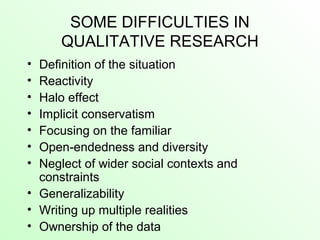

This document outlines key concepts and approaches in naturalistic, qualitative, and ethnographic research. It discusses the foundations and stages of such research, including planning, data collection methods like observation and interviews, analysis involving inductive theory generation, and addressing issues like reflexivity and negotiating entry into research sites. Challenges like reactivity and representing multiple realities are also covered.