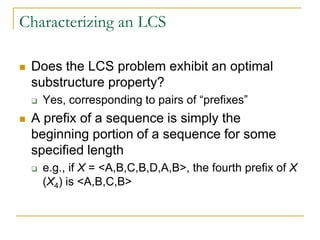

Dynamic programming is used to solve optimization problems by breaking them down into overlapping subproblems. It is applicable to problems that exhibit optimal substructure and overlapping subproblems. The matrix chain multiplication problem can be solved using dynamic programming in O(n^3) time by defining the problem recursively, computing the costs of subproblems in a bottom-up manner using dynamic programming, and tracing the optimal solution back from the computed information. Similarly, the longest common subsequence problem exhibits optimal substructure and can be solved using dynamic programming.

![A Recursive Solution

Our subproblem is the problem of

determining the minimum cost of a

parenthesization of Ai,…,Aj, where 1 <= i <= j

<= n

Let m[i,j] be the minimum number of

multiplications needed to compute Ai..j

Lowest cost to compute A1..n is m[1,n]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter16-140325170008-phpapp02/85/Chapter-16-12-320.jpg)

![A Recursive Solution

How do we recursively define m[i,j]?

If i = j, no multiplications are necessary since we never

have to multiply a matrix by itself

Thus, m[i,i] = 0 for all i

If i < j, we compute as follows:

Assume that there is some optimal parenthesization that splits

the range between k and k+1

m[i,j] = m[i,k]+m[k+1,j]+pi-1pkpj, per our previous discussion

To do this, we must find k

There are j-i possibilities, which can be checked directly](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter16-140325170008-phpapp02/85/Chapter-16-13-320.jpg)

![A Recursive Solution

Our recursive solution is now:

m[i,j] gives the costs of optimal solutions to

subproblems

Define a second table s[i,j] to help keep track of

how to construct an optimal solution

Each entry contains the value k at which to split the

product

ji

ji

pppjkmkim

jim

jki

jki

if

if

}],1[],[{min

0

],[

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter16-140325170008-phpapp02/85/Chapter-16-14-320.jpg)

![MatrixChainOrder(const double p[], int size, Matrix

&m, Matrix &s)

{

int n = size-1;

for ( int i = 1 ; i <= n ; ++i )

m(i,i) = 0;

for ( int L = 2 ; L <= n ; ++L ) {

for ( int i = 1 ; i <= n-L+1 ; ++i ) {

for ( int j = 0 ; j <= i+L-1 ; ++j ) {

m(i,j) = MAXDOUBLE;

for ( int k = i ; k <= j-1 ; ++k ) {

int q = m(i,k)+m(k+1,j)+p[i-1]*p[k]*p[j];

if ( q < m(i,j) ) m(i,j) = q;

else s(i,j) = k;

} // for ( k )

} // for ( j )

} // for ( i )

} // for ( L )

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter16-140325170008-phpapp02/85/Chapter-16-18-320.jpg)

![Constructing an Optimal Solution

So far, we only know the optimal number of scalar

multiplications, not the order in which to multiply the matrices

This information is encoded in the table s

Each entry s[i,j] records the value k such that the optimal

parenthesization of Ai…Aj occurs between matrix k and k+1

To compute the product A1..n, we parenthesize at s[1,n]

Previous matrix multiplications can be computed recursively

E.g., s[1,s[1,n]] contains the optimal split for the left half of the

multiplication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter16-140325170008-phpapp02/85/Chapter-16-21-320.jpg)

![Constructing an Optimal Solution

MatrixChainMultiply(const Matrix A[], const Matrix &s, int

i, int j)

{

if ( j > i )

{

Matrix X = MatrixChainMultiply(A, s, i, s(i,j));

Matrix Y = MatrixChainMultiply(A, s, s(i,j)+1, j);

return MatrixMultiply(X,Y);

}

else

return A[i];

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter16-140325170008-phpapp02/85/Chapter-16-22-320.jpg)

![Overlapping Subproblems

From the matrix-chain algorithm, we see earlier

computations being reused to perform later

computations:

What if we replaced this with a recursive

algorithm?

Figure 16.2 on page 311 shows the added

computations

int q = m(i,k)+m(k+1,j)+p[i-1]*p[k]*p[j];

if ( q < m(i,j) )

m(i,j) = q;

else

s(i,j) = k;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter16-140325170008-phpapp02/85/Chapter-16-26-320.jpg)

![A Recursive Solution To Subproblems

What is the cost of an optimal solution?

Let c[i,j] be the length of an LCS of Xi & Yj

If i or j = 0, then the LCS for that subsequence has length 0

Otherwise, the cost follows directly from Theorem 16.1:

ji

ji

yxji

yxji

ji

jicjic

jicjic

and0,if

and0,if

0or0if

],1[],1,[max(

1]1,1[

0

],[](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter16-140325170008-phpapp02/85/Chapter-16-35-320.jpg)

![Computing the Length of an LCS

The following algorithm fills in the cost table c

based on the input sequences X and Y

It also maintains a table b that helps simplify an

optimal solution

Entry b[i,j] points to the table entry corresponding to the

optimal subproblem solution chosen when computing

c[i,j]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter16-140325170008-phpapp02/85/Chapter-16-37-320.jpg)

![Computing the Length of an LCS

// Fill in tables

for ( int i = 1 ; i < m ; ++i )

for ( int j = 1 ; j < n ; ++j ) {

if ( x[i] == y[j] ) {

c(i,j) = c(i-1,j-1)+1;

b(i,j) = 1; // Subproblem type 1 “ã”

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter16-140325170008-phpapp02/85/Chapter-16-39-320.jpg)